Aadhaar Case: Beyond Privacy, An Issue of Bodily Integrity

The article was published in the Quint on May 1, 2017.

The Finance Act, 2017, among its various sweeping changes, also inserted a new provision into the Section 139AA of the IT ACT, which makes Aadhaar numbers mandatory for:

(a) applying for PAN and

(b) filing income tax returns

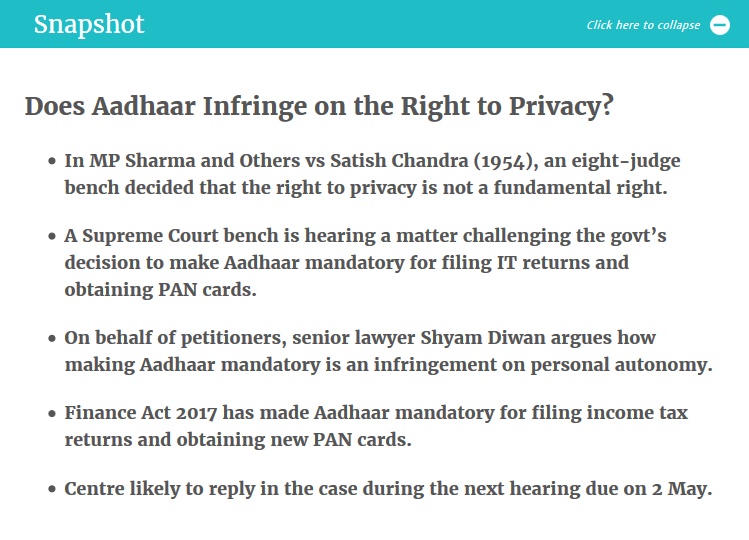

In case one does not have an Aadhaar number, she or he is required to submit the enrolment ID of one’s Aadhaar application. The overall effect of this provision is that it makes Aadhaar mandatory for filing tax returns and applying for a PAN. The SC hearings began on 26 April. In order to properly appreciate the tough task at hand for the counsel for the petitioners, it is important to do a quick recap of the history of the Aadhaar case.

Case Over Constitutional Validity

Back in August 2015, the Supreme Court had referred the question of the constitutional validity of the fundamental right to privacy to a larger bench.

This development came after the Union government pointed out that the judgements in MP Sharma vs Satish Chandra and Kharak Singh vs State of UP (decided by eight and six judge benches respectively) rejected a constitutional right to privacy.

The reference to a larger bench has since delayed the entire Aadhaar case, while an alarming number of government schemes have made Aadhaar mandatory in the meantime.

Since then, the Supreme Court has not entertained any arguments related to privacy in the court proceedings on Aadhaar pending the resolution of this issue by a constitutional bench, which is yet to to be set up. The petitioners have had to navigate this significant handicap in the current proceedings as well.

Ongoing Hearing in Aadhaar Case

At the beginning of Advocate Shyam Divan’s arguments on behalf of the petitioners, the Attorney General objected to the petitioners making any argument related to the right to privacy. Anticipating this objection, Divan assured the court, right at the outset that they “will not argue on privacy issue at all”.

In the course of his arguments, Divan referred to at least three rights which may otherwise have been argued as facets of the right to privacy – personal autonomy, informational self-determination and bodily integrity. However, in this hearing those rights were strategically not couched as dimensions of privacy.

Divan consistently maintained that these rights emanate from Article 21 and Article 19 of the Constitutions and are different from the right to privacy.

Many Layers of the Right to Privacy

If one follows the courtroom exchanges in the original Aadhaar matter (not the one being argued now), the debates around the privacy implications of Aadhaar have focussed on simplistic balancing exercises of “security vs privacy” and “efficient governance vs privacy”.

These observations depict the right to privacy as a monolithic concept, i.e. a single right which has a unity of harm it captures within itself. In other words, all privacy harms are considered to be on the same footing. "Privacy harms" here mean the undesirable effects of the violation of the right to privacy.

This monolithic conception was clearly reflected in the Supreme Court’s decision to refer the constitutionality of “right to privacy” to a larger bench.

In MP Sharma vs Satish Chandra, the Supreme Court had rejected certain dimensions of what is generally understood as the right to privacy in a specific context (and hence dealing with a specific kind of privacy harm). A monolithic conception of the right to privacy would mean that MP Sharma should be applicable to all kinds of privacy claims.

Prof Daniel Solove, a privacy law expert, in his landmark paper “Taxonomy of Privacy” argues that the right to privacy captures multiple kinds of harms within itself. The right to privacy is not a monolithic concept, but a plural concept; there is no one right to privacy, but multiple hues of right to privacy.

Sidestepping ‘Privacy’ in the Current Case

The plural conception of the right to privacy not only makes our privacy jurisprudence more nuanced and comprehensive, but also guides us to analyse differential privacy harms according to the standards appropriate for them.

Therefore, the refusal of the Supreme Court in MP Sharma to recognise a specific construction of privacy read into a specific constitutional provision should not have precluded the bench, even one smaller in number, from treating other conceptions of privacy into the same or other constitutional provisions.

As a lawyer, Divan was severely compromised from being unable to argue the right to privacy, which in my opinion, cuts at the heart of the constitutional issues with the Aadhaar project.

He refrained from couching any of his arguments on bodily integrity, informational self-determination, and personal autonomy as privacy arguments. What the approach reveals is that far from being a monolithic notion, the harms that privacy, as we understand it, addresses, are capable of being broken into multiple and distinct rights.

Moving Beyond Article 21

Divan further argues that coercing someone to give personal information is compelled speech and hence, violative of Article 19(1)(a) (the rights to free speech and expression). Once again, the harm described here – compelling someone to part with personal data – is conventionally a privacy harm.

However, it is important to note here that a privacy harm may also be a speech harm. Therefore, Article 21 is not the sole repository of these rights. They may also be located under other articles. The practical consequence of these rights being located under multiple constitutional provisions could be added protection of these rights.

For instance, if it can be shown that compelling an individual to part with personal data results into violation of Article 19(1)(a), the State will have to show which ground laid down under Article 19(2) does the specific restriction fall under.

This might be more challenging as opposed to the vague standard of “compelling state interest” test which has been the constitutional test for privacy violations under Article 21.

Changing the Definition of Right to Privacy

The arguments presented by Divan, if accepted by the Supreme Court, could represent a two-pronged shift in the landscape of the values popularly understood under the right to privacy in India:

1) first, the idea of the rights of bodily integrity, informational self-determination, and personal autonomy as part of a plural concept (whether arising from the right to privacy or another right) that encompasses several harms within it, and

2) second that some of these rights may be read into other Articles in the Constitution.

Under the circumstances, Mr Divan’s performance was nothing short of heroic. Whether they pass muster and impact the course of this long drawn legal battle remains to be seen.

(Amber Sinha is a lawyer and works as a researcher at the Centre for Internet and Society. Aradhya Sethia is a final year law student at the National Law School of India University, Bangalore. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)