Technological beasts like Facebook, Orkut, YouTube & Google impossible to control

Becoming the voice of a generation was never the agenda. Neither was toppling governments or inciting riots. But technological beasts are impossible to tame. And social networking sites (SNWs), made up of millions of lives, have morphed into the most unpredictable monster yet.

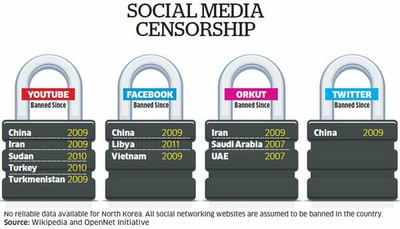

What started as online hangouts, have become a melting pot of opinions and ideas. Facebook, Orkut, YouTube and Google+, enjoy power of the collective, bolstered by technology that allows real-time interaction and blurs physical distances. The effect has shaken up the world: Wall Street to West Asia.

But the government ought to have been smarter than to call the biggest social media intermediaries, Yahoo, Google, Facebook and Microsoft, into a closed door meeting and force stricter rules. The news leaked, and the beast became angry. Social network users have gone into a frenzy to protect their rights.

Kapil Sibal, communications minister, held a press conference to highlight the kind of user-content that the government opposes. He clarified the government wants pre-screening not censoring. But SNW followers have paid no heed. For any external control taints the idea of an online hangout.

But one can't wish away perverseness. And Sibal is not completely wrong, there is plenty of it on SNWs. The question is, who should take it down? Users, hosts or the government?

Extra Rules Not Required

The country has not been running without cyber laws. So why invent new ones for the social media? "Rules are already in place, the Information Technology Act, 2000 and Information Technology Rules, 2011, which allow anyone, including the government, to take a legal recourse," says Pawan Duggal, advocate in the Supreme Court of India and a cyber law expert.

Section 2(1) of IT Act defines an "intermediary" as any person who on behalf of another person receives, stores or transmits a message or provides any service with respect to that message. By this definition, an intermediary is just a messenger. SNWs, internet service providers and web hosts fall in this category.

Changes and additions to the IT laws have already made their job tough. SNWs are responsible for taking down all potentially problematic content as and when requested. There is a time limit too: 36 hours to respond to such a request. If an SNW refuses to do so, it can be dragged to the court as a co-accused.

Duggal says that web hosts can be prosecuted if they create unlawful content, incite and encourage unlawful activities, or fail to remove illegal content despite it being brought to their notice. So why does the government suddenly want more rules for them?

Asking for the Moon

No one's denying the need for regulation. And SNWs have good regulators: millions of users. If even one finds a post offensive, he or she can report abuse. The nomenclature may be different, but every host of user-generated content has this option.

The problem is there's no scale to measure what offends sensibilities. There's a list of items that are considered illegal but they are not defined. For instance, "harmful to minors", makes the cut, but what qualifies as harmful is unclear. Even pornography is not defined by Indian laws.

This is why the government may not be wrong to be on tenterhooks. But its solution to the problem is untenable: both conceptually and technologically. "A pre-screening mechanism is not impossible. Tools and algorithms to monitor social media content are constantly evolving. But considering the scale of FB, YouTube, Twitter, etc, it will definitely affect real-time interaction," says Shree Parthasarathy, senior director, enterprise risk services, Deloitte, a consultancy.

Numbers corroborate the view. In India itself, there are almost 43 million users on Facebook, 3.6 million on Google Plus and 3.5 million on Twitter. Worldwide, YouTube uploads more than 48 hours of video every minute. Imagine an army of employees monitoring each post by referring to a catalogue of words considered unacceptable and a repository of images that are deemed inappropriate or offensive.

"The question is not whether it's possible but whether it's appropriate. Such a move will require extensive investment in infrastructure," says Parthasarathy.

Advith Dhuddu, founder of AliveNow.in, a social media firm based in Bangalore, says: "Technology doesn't understand sentiments or sarcasm. It won't distinguish between a porn clip or a video on sex education." Further, even if India decides to monitor content within the subcontinent, it cannot control what's created outside of the country.

Anti-intermediary Legacy

India has never been a favourite among web hosts. IT laws here have always been stricter than in the West and despite amendments, the burden of responsibility on intermediaries is high. "If pre-screening kicks in, web hosts will not be able to claim they did not know about any contentious material on their sites as they will have a seal of approval. This will undermine the sites' legal immunity, a big worry for web hosts," says Sunil Abraham, executive director of the Centre for Internet and Society (CIS).

Outside India, there's differential treatment for different kinds of intermediaries, the principles of natural justice are implemented and there are options for counter notices and notifications. For instance, in Brazil, as per a draft bill, if someone sends three fraudulent take-down notices, he will not be allowed to send a take-down notice again for a year.

Before 2008, things in India were worse. Intermediaries were liable for their user's content. This led to the arrest of Bazee.com chief, Avnish Bajaj, in connection with the sale of the infamous DPS Noida MMS clip CD on the website.

Post the Bazee.com fiasco, IT laws have been amended. But according to Abraham, "There is still no principle of natural justice, no differentiation between different types of intermediaries and no penalty for abusing."

No wonder social media is over cautious. An unpublished report by the CIS claims intermediaries err on the side of caution and "overcomply" when take-down notices are sent. The researcher sent fraudulent notices to seven intermediaries, including prominent search engines and hosts, identifying specific user-generated material as offensive.

"Of the seven intermediaries to which take-down notices were sent, six over-complied...Not all intermediaries have sufficient legal competence or resources to deliberate on the legality of an expression, as a result of which, intermediaries have a tendency to err on the side of caution," says the report.

No Muzzle, Just Checks

The bottom line is: government control will take the fun away from SNWs. Imagine an invisible monitoring authority checking out pictures of a party before your friends and family can. It is creepy. It also hints at repression, of the kind China specialises in. No thank you, we are not competing in this department.

Some people believe the government doesn't intend to censor SNWs, it just goofed up on the communication. "Sibal is right in saying that obscenity in real and cyber space is the same. He bungles when he puts an insult to the Prophet, Sonia Gandhi and Manmohan Singh in the same bracket. Had he put the debate in a different form, citizens might have appreciated that he's desperately trying to do a good job," says sociologist Shiv Vishwanathan.

If that's true, government officials can start a page: "I like social networks". That is a language we all understand.

This article by Sunanda Poduwal & Kamya Jaiswal was published in the Economic Times on December 11, 2012. Sunil Abraham was quoted in this. Read the original here