Mapping Institutions of Intellectual Property: Part C — Comparing Intellectual Property Institutions

View Parts A and B here and here

Preliminary

Intellectual Property Institutes/Institutes of Intellectual Property (“Institutes”) world over usually perform two kinds of functions- first, they may serve as the Intellectual Property Office (the nodal agency for matters relating to intellectual property) in their respective countries and second, they may provide policy inputs to their respective governments. From discussions at a Stakeholders Consultation in New Delhi earlier this year (which I have written about here and here), it emerged that the Indian government (specifically, the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, India’s nodal agency for IPR related matters except copyright, and the MHRD, India’s nodal agency for copyright related matters ) lacked an institutional framework for policy feedback to the government, which in turn would supplement international negotiations. In order to address this lacuna, the Planning Commission and the MHRD presented a proposal (“the Proposal”) to set up the NIIPR, which would, inter alia, perform the function of advising the Indian government on matters of intellectual property law and policy and inform international negotiations pursuant to the same. This article examines Institutes other jurisdictions on the basis of their functions, and attempts to ascertain what functions an ‘ideal’ Institute might perform.

Methodology and Preliminary Findings

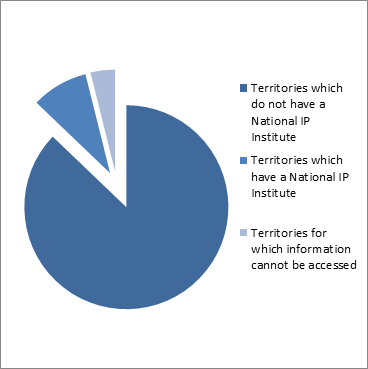

A list of two hundred and fifty seven territories was prepared and attempts were made to trace Institutes in each of these territories. Out of these, those Institutes that had websites, and whose websites had content available in English (or for which an official or credible translation was available) were earmarked. Once the Institutes had been thus identified, their distinctive features and past achievements were studied on the basis of disclosures available on the websites of the Institutes.

It emerged that twenty three (23) countries had Institutes that performed functions similar to those envisaged for the proposed NIIPR. These countries include Albania, Australia, Belarus, Belgium, Belize, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Chile, France, Gabon, Greece, Iceland, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Malaysia, New Zealand, Pakistan, Portugal, Romania, Switzerland, Taiwan and Vietnam. However, this number cannot be said to be exhaustive as for 10 Countries, the translated page could not be availed. Further, in a few countries including Belgium, Belize, Iceland, New Zealand, Trinidad and Tobago, Sri Lanka and United States, the Intellectual Property Office performed the additional function of providing policy inputs to the government, in addition to administering and granting Intellectual Property Rights.

A diagrammatic representation of these preliminary findings and the methodology is available in Figures 1 and 2 (below).

|

|---|

| Figure 1 |

|

|---|

| Figure 2 |

Observations on Functions

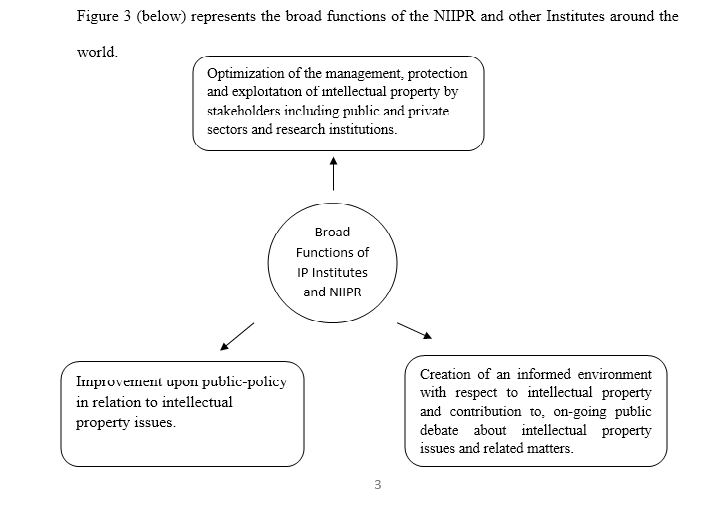

|

|---|

| Figure 3 |

Institutes across the world are varied in their functioning, structure and organization. Some observations (that could aid the establishment of the NIIPR) on the functioning of some of these Institutes are as under:

- The Institute for Intellectual Property Rights of Bosnia and Herzegovina performs a dual role of the Patent Office as well as that of a research institute. In addition to assisting the government when it enters into agreements, it also performs documentation tasks and implements regulations related to intellectual property. It is also entrusted with the task of maintaining a record of industrial property applied for and granted.

- The National Institute of Industrial Property, France contributes to the development and implementation of public policies in the field of anti-counterfeiting.

- The Centre for Industrial property of Gabon presents and defends the interests of the Gabonese government at the international level.

- The Hellenic Industrial Property Organisation registers inventions in Greece by granting patents and utility model certificates. It also registers industrial designs and community designs and models. Moreover, it also acts as a receiving office for the European Patent and the PCT certificate among others.

- The National Institute of Intellectual Property, Kazakhstan performs the functions of the National Patent Office, including examination of applications for patents, useful models, trademarks, appellation of origin of goods and industrial designs.

- The Intellectual Property Organization, Pakistan seeks to serve as the nodal organisation for the integrated management of intellectual property and seeks to coordinate the enforcement of intellectual property as well.

- The Swiss Federal Institute of Intellectual Property performs the task of examining national filing applications and grants and administers intellectual property rights. It has also developed a patent database (ESPACEMENT) which has ensured access to over eighty (80) million patent documents.

- The Japanese Institute of Intellectual Property provides inputs on existing laws to the Government of Japan. These inputs have influenced the revision of Japanese laws relating to patents, trademarks, utility models and the prevention of unfair competition.

Takeaways for the NIIPR

This attempt at an overview of Intellectual Property Institutes around the world has revealed broad similarities in their functioning. These similarities are also seen with the proposed functions of the NIIPR, as outlined in the Proposal of the MHRD and the Planning Commission. It would therefore lead one to believe that the establishment of this institution is potentially headed in the right direction. However, even while the functions of these existing Institutions might guide the establishment of the NIIPR, it would do well to tailor itself to meet India’s specific requirements. With pre-existing ministries, departments and offices in place to deal with the enforcement of intellectual property rights, India needs a body that informs the government on issues of intellectual property law and policy reform, in preparation for international negotiations, which is a lacuna that the NIIPR ought to address. In addition to this core function, the NIIPR may be the institution that oversees the role and functioning of the MHRD Chairs, and also be developed as a research institution aiding the government in developing an intellectual property framework addressing the needs of all stakeholders. Further, the NIIPR may also consider undertaking activities such as the establishment of databases containing patent documents and other publications in Indic languages to ensure access to a larger group of people. The NIIPR could also play an influential role in shaping regional discussions on intellectual property at the international level and encourage and facilitate South-South dialogue.

With nine thousand nine hundred and eighty (9980) lakh Indian rupees being allocated for the National Programme on Intellectual Property Management under the current Five Year Plan (2012-2017), which includes the establishment of the NIIPR, one awaits further developments that might well change the face of India’s intellectual property framework in the long run, with a sense restrained excitement.