National IPR Policy: Mapping the Stakeholders’ Response

Nehaa Chaudhari provided inputs and feedback and also edited this post.

I. Introduction

On 24th December 2014, the IPR Think Tank constituted by the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP) officially released the first draft of the National IPR Policy. Following this, in a press release dated 30th December, 2014, the DIPP called for comments and suggestions on the draft from all stakeholders. CIS, through an RTI, asked the DIPP to disclose all the comments received by it. However, the DIPP’s reply, rather vague, stated that it is not in the position to provide the same. (Further details here).

II. Research Methodology

In this post, I have compiled and compared the various submissions that I was able to find online in a SpicyIP post and will provide an analysis of the same.

The spreadsheet that I have created contains a compilation of the many issues that were raised by 15 stakeholders of various affiliations (organisations/scholars/unions). This spreadsheet was put together after reading each submission carefully, and summarizing the same. After dividing the contents of the submissions into the various issues, they were put under certain heads in this sheet. Though there were a few ideas covered by certain submissions that have not been tabulated, all the major and important ones have been covered, in my opinion.

On the basis of this spreadsheet, the following observations have been made on the feedback of the many stakeholders on the various aspects of the draft.

III. Stakeholders - A Statistical Analyis

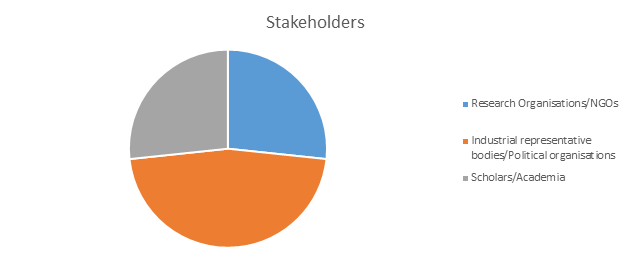

A total of 15 submissions were taken into consideration for the purpose of this post, and all of them applauded the government for recognizing of the need for a comprehensive policy on IP and the DIPP’s efforts to give the public a chance to play a role in the process of formation of a policy that would affect the country and its economy significantly. However, each submission had its own set of criticisms and suggestions to the various aspects dealt with by the policy. In my analysis there are three broad categories that the stakeholders can be divided into:

- Research organisations/NGOs.

- Industrial representative bodies/Political organisations.

- Scholars/Academia.

A representation of the stakeholders and the categories that they belong to has been produced below.

| Categories | Stakeholders |

|---|---|

| Research organisations/NGOs | Centre for Internet and Society (CIS); Consumer Unity & Trust Society (CUTS); Software Freedom Law Centre (SFLC); Centre for Law & Policy Research (CLPR). |

| Industrial representative bodies/Political organisations | Intellectual Property Owners Association (IPO); National Association of Manufacturers (NAM); International Trademark Association (INTA); IP Federation – UK; ICC’s Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy (BASCAP); Swadeshi Jagaran Manch (SJM); American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham – India). |

| Scholars/Academia | Centre for Intellectual Property and Technology Law – O.P. Jindal Global University (CIPTEL); S. Ragavan, B. Baker, S. Flynn; Adv. Ravindra Chingale – NLU Delhi; Prof. N.S. Gopalakrishnan & Dr T.G. Agitha – CUSAT. |

Out of the comments studied, the largest chunk of stakeholders (46.67%) belonged to the industrial/manufacturing sector, with the other two categories comprising only 26.67% each. This could be attributed to the fact that a country’s IPR policy has a very vital role to play in influencing an industrial firm’s strategy and an unsatisfactory policy could have a serious and adverse effect on the profit-making abilities of an industry.

IV. IP - Innovation / Growth Nexus

There are a total of 13 themes that have been identified in the spreadsheet, and out of these 13, the one that the largest number of stakeholders has commented on is the question of there being nexus between intellectual property, innovation and growth. Eleven out of the fifteen stakeholders have given their opinion on this issue.

The opinion on this theme is not very uniform. Some organisations are of the opinion that there is a strong correlation between robust IPR protection mechanisms and innovation in a country, and thus there is a resultant benefit to the economy of the country. For example, the IP Federation of UK claimed that with a strong IPR regime, there is a greater inflow of FDI and R&D expenditure in countries, thus benefitting the country’s economy. On the other hand, there are some stakeholders who believe that there is no nexus and that the underlying assumption made by the draft policy is not backed by any research or evidence. The Centre for Internet and Society (CIS), for example, even cites evidence in its submission to oppose this assumption. The smallest chunk of stakeholders suggests to the Think Tank that in the current draft, there is not enough authority cited by them, and thus, there should be some research that must be done in order to give this assumption some backing. CIPTEL, a research centre based in OP Jindal Global University, stated that there should be a transparent survey conducted on this issue by a neutral agency.

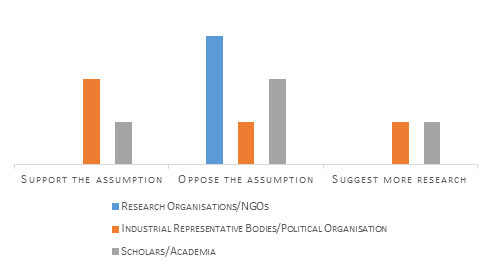

The figure below would give the reader a comparative analysis of the responses from the stakeholders on this particular theme.

All the research organisations/NGOs that presented their views on this assumption are in opposition to the same and have proposed to the Think Tank that it should amend the contents of the policy after taking this incorrectly-made assumption out of the mix.

A majority of the industrial bodies have supported the existence of a nexus and have stated that by enforcing stronger IPR protection laws, the innovative/inventive environment of a country develops and this in turn encourages investors, which culminates into a rise in the growth of the economy.

Scholars and academia have a difference of opinion amongst themselves and there is no uniform pattern that can be seen in their responses to this issue.

The only political organisation in this analysis, the Swadeshi Jagaran Manch opposes the assumption and states that the policy has turned a blind eye to the development of the country and that there is no analysis on whether there is any effect of the proposed strengthening of IP protection on the various sectors of the economy.

V. International Treaties

The policy, in its introduction states the following stance on negotiation of international treaties and agreements – “In future negotiations in international forums and with other countries, India shall continue to give precedence to its national development priorities whilst adhering to its international commitments and avoiding TRIPS plus provisions.”

On this general theme, 9 out of 15 stakeholders have submitted their comments to the Think Tank. Out of these 9, the category-wise division of the stakeholders is represented by the diagram below.

The opinion of the stakeholders on this issue varied and there were broadly 3 kinds of responses that were found in the analysis. More than half of these responses (56%) suggested that all negotiations of treaties must be done transparently, with proper consultation of all stakeholders. CUTS, for example, recommended that to increase the confidence of the people in the country’s IP regime, the negotiations must be done with the opinion of all stakeholders being taken into consideration. They also cautioned the government to make sure that any future agreements do not contain any TRIPS-plus provisions. The second category applauded the policy’s pro-global stance towards IPR developments, and has recommended certain treaties that India must sign in order to strengthen its regime (details in spreadsheet). Only one stakeholder, the National Association of Manufacturers of the USA suggested that India’s stance of avoiding TRIPS-plus agreements is in contravention to its objective of keeping up with global IP developments. This point of view is clearly in favour of the USA as TRIPS-plus provisions have always been more beneficial to developed countries than developing countries like India.

Thus, it can be said that almost 90% of stakeholders, from across categories, are satisfied with India’s pro-international stance, and only want the government to be cautious and consult the public before signing treaties on IPR.

VI. Utility Models

A provision to legalise utility model protection was also a part of the draft policy. Utility models or petty patents are suggested by the policy in order to protect parties like MSMEs and their many innovations which may not satisfy the requirements of regular patent protection and thus losing out from IPR protection, leading to benefits not being reaped properly from these inventions.

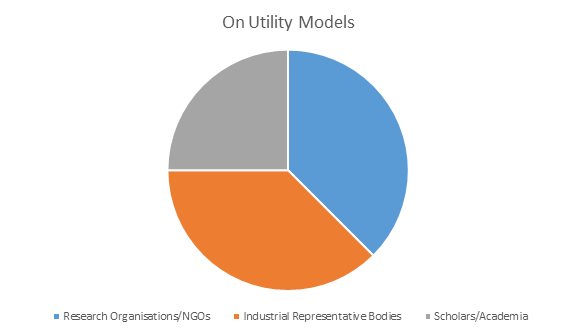

This provision was commented on by eight of the 15 stakeholders, making it a little above half of the total. A category-wise division can be found below.

The opinion on utility models was majorly negative across categories, with 75% of the stakeholders believing that utility model protection must be given a second thought and many drawbacks were pointed out such as frivolous litigation, uncertainty in the market, and a drop in the quality of innovation registered in the country. A review of how effective utility model laws are in other countries was suggested before making any final decision. Only 2 out of the 8 stakeholders supported the provision for petty patents and stated that this would give a good means of protection to ‘jugaad’ innovations that are very popular in India and thus believed that such laws would help increase the innovation levels in the country.

VII. Public Funded Research Labs and Universities

Only four stakeholders had a say on the issue of grants to Government labs and universities, these organisations being Indian research organisations and academia. The opinion varied from party to party and the Centre for Internet and Society argued that if there was a rise in IP protection for government funded research, it would be against the vision of free and open access to research funded by taxpayers’ money.

The other three stakeholders, namely CIPTEL, CUTS and Adv. Ravindra Chingale emphasised on the importance of merit-based funding instead of funding on the basis of whether an organisation is Government-owned or not. Two of these also suggested that there must be a system of contact between industry and academia to incentivise and utilize innovation properly.

VIII. Limitations and Flexibilities

A very important aspect of any IPR regime is the presence of limitations, exceptions and flexibilities on the rights protected by IP laws, as it allows for the appropriate amount of information being shared for free or at reasonable costs, for furtherance of public interest.

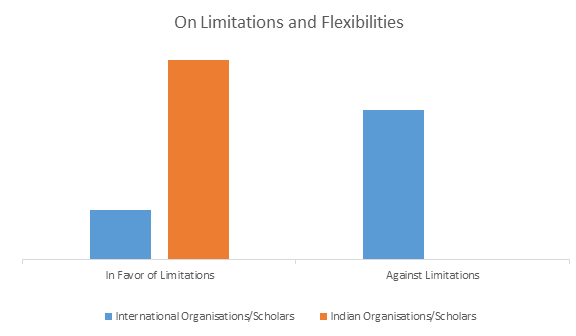

On this vital issue, most stakeholders had a say and the trends of the feedback on the limitations and flexibilities on IP protection were as expected. There were two broad sets of opinions that could be gathered from the analysis, and while there was a majority (62.5%) of organisations and people who believed that the government must keep up its efforts of providing a good framework for exceptions to IPR protection with measures like compulsory licensing being put in place in order to protect broader interests of the country such as access to reasonably priced medicines and other necessities. The only recommendation that they had was that these measures should be decided after a careful analysis of what the economy really needed in order to develop further.

The opposition, quite understandably came from international industrial bodies representing manufacturers and intellectual property owners who argued that the policy of limitations to IPR protection is discouraging those who want to invest in the country and that it hurts the business of foreign-based companies that operate in India or want to do so in the near future as their intellectual property may not be protected adequately with such a policy in place.

The figure above clearly points out that none of those against limitations being placed on IP protection had an Indian background and all those in favour of the same were primarily Indian-based organisations and academics, with the exception of the American scholars – S. Ragavan, B. Baker, and S. Flynn.

IX. Trademarks

Only a single stakeholder, the International Trademark Association, was interested in the issue of trademarks. This can be attributed to the fact that this is the only association out of all the stakeholders having a direct interest in trademark law and policy. The organisation suggested that there should be a greater amount of clarity in the trademark examination process and also suggested that there should be an increase in the number of examiners to make the process of trademark registration quicker.

X. Trade Secrets

In objective 3 of the draft policy, the Think Tank suggests that to strengthen the IP framework of the country, trade secret protection must be introduced as a formal law. India, today, does not have a law to protect sensitive trading information and there needs to be a formalised contract for there to be any relief for leaking of such information.

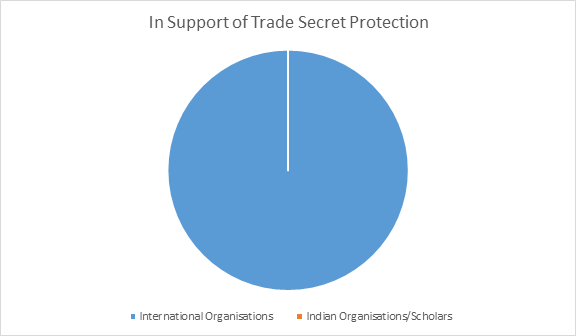

The stakeholders supporting the enactment of trade secret legislation were interestingly all industrial bodies representing international companies and firms. Only 2 parties expressed their worries about such a law, and argued that there must be more backing to make this recommendation more convincing. A graphical representation of the stakeholders is given below to provide a clearer picture of the responses.

This chart portrays clearly that international bodies are insistent on the enactment of a trade secret law as this would help incentivise knowledge sharing in the country. In many countries, trade secret protection is formalised legally and these stakeholders argue that for foreign multinationals to feel confident while sharing sensitive information with others in India, the government must follow in the footsteps of such countries and legislate on this matter soon.

XI. On Specialised Courts

A common suggestion found across 5 of the 15 stakeholder responses was for the creation of a specialised IP judiciary that would be formed by widening the patent bench that was proposed in the draft policy. Such a court would deal only with issues of intellectual property and would consist of judges having special knowledge in the various branches of IP law.

XII. Conclusion

The draft policy was released almost a year ago, and since then, much discussion has taken place on the same, with many contradictory opinions and suggestions on the various aspects of the policy. It can be observed from this compilation that industrial bodies have been insistent on stronger IP protection and more incentives to multinationals to invest in India in the form of trade secret legislations, keeping limitations such as compulsory licensing to a minimum, et al.

On the other hand, a trend could be seen of research organisations and academia having a view that was more in the interest of the public and with the Indian scenario taken into consideration, with the criticism of utility models, TRIPS-plus agreements, and by raising the question of whether the assumption underlying the draft of there being a link between IP protection and a rise in innovation had any basis whatsoever. This post, however, is only a glimpse of the stakeholders’ responses owing to the fact that the DIPP has not officially released the submissions made to it and only the ones that were available online have been taken into consideration.

It is only a matter of time that the Think Tank releases the final policy and one shall hope that this tedious process of seeking comments and suggestions will bear any fruit with the policy being a balanced one and being aimed ultimately towards the benefit of the country as a whole.