India’s missing disabled population

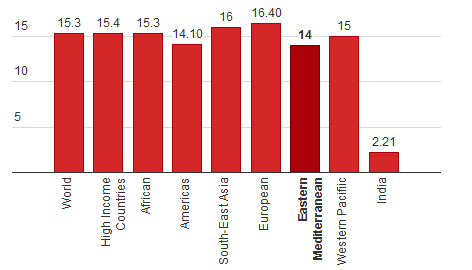

The World Health Organisation in a report in 2011 estimated that 15.3% of the world’s population deals with disability of one kind or the other. The 2011 census puts India’s disabled at 2.21% of the population. Photo: AFP

The article by Sachin P. Mampatta was published in Livemint on September 7, 2015. Nirmita Narasimhan gave her inputs.

Nirmita Narasimhan remembers the census takers coming to her home. They didn’t ask her question number nine. It was about disability. They said that it makes people uncomfortable.

Narasimhan is a policy director who works on disability issues at The Centre for Internet and Society, an NGO. She insisted that they ask questions on disability. Later, she found out that others too had a similar experience. Those conducting the census often skip the question. Sometimes families are reluctant to talk about it too.

The result is that India has far lower reported instances of disability than most other places in the world. This also means that policy action is effectively running blind, unsure of the scale of the disability issues in the country or its specifics.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) in a report in 2011 estimated that 15.3% of the world’s population deals with disability of one kind or the other. The 2011 census puts India’s disabled at 2.21% of the population.

India's low incidence of disability

The average number of disabled people in India is lower than the global figure as well as the number for high income countries. It is also lower than the corresponding figures for low-income and middle-income countries (between and including African to Western Pacific in the chart).

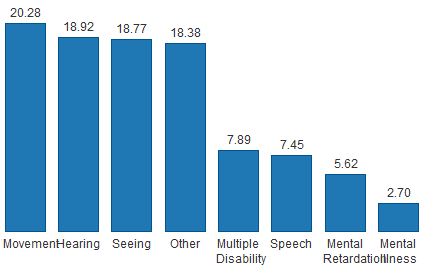

Different categories as percentage of total disability

Disabilities related to movement, hearing and sight are the most common, according to the Census

|

|---|

|

Above: A bar chart depicting the world population with disability. India is at lowest. Source: Global Burden of Disease estimates for 2004 (World report on disability |

The latest census number is not very different from that of the 2001 census when the disabled populace was at 2.13% or from the 2002 National Sample Survey figure which estimated this figure at 1.8%. That just points out for how long the problem has been prevalent in official statistics.

The WHO report used statistics from the Global Burden of Disease estimates for 2004 for comparison. But the situation now is likely to be worse. A WHO factsheet says that “rates of disability are increasing in part due to ageing populations and an increase in chronic health conditions”.

Many people don’t disclose disability because of stigma. Global figures also take into account age-related disability, and those whose function is affected by issues such as diabetes. India does not count these among the disabled. Here, the categories are largely traditional such as blindness and deafness. The highest rates of disability are amongst those who are vision-impaired, and those who have problems to do with movement.

Different categories as percentage of total disability

Disabilities related to movement, hearing and sight are the most common, according to the Census.

|

|---|

| Above: A bar chart depicting the percentage of various forms of disabilities |

While the scope of definitions is part of the problem, India’s disability estimation problem is not unrecognized.

“In India, the disability sector in general estimates that 4-5% of the population is disabled. The Planning Commission recognizes this figure as 5%. A report by the World Bank states that while estimates vary, there is growing evidence that persons with disability… constitute between 4-8% of India’s population,” said a December 2011 International Labour Organisation report by Meera Shenoy called, “Persons With Disability and the Indian Labour Market: Challenges and Opportunities”.

The lower-than-actual figures have other repercussions. What’s the literacy rate among the disabled, for instance? The census, of course, says that more than 54.51% of India’s disabled population is literate. But policy analysts such as Narasimhan say that may be inflated again because of under-reporting.

“The Sarva Shiksha Abhiyaan has contributed to getting a lot of children into school, and the thrust has largely been seen over the last decade or so. Unfortunately, many may not be able to continue in school, though they do manage to attend for a couple of years. This may be enough for them to pick up sufficient skills to be declared literate, where the test is generally rudimentary, say the ability to write your own name. But this does not translate into employability. The majority would still not be able to meet basic criteria required for landing a job. The resources required to make this happen is far in excess of the current expenditure,” said Dipendra Manocha, president, founder and managing trustee, Saksham Trust.

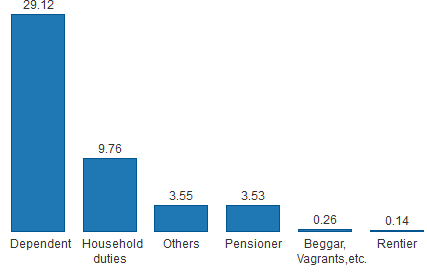

Census data shows that 63.66% of the disabled population is not working compared to 60.21% of the able-bodied. But those working in the field say that employability figures are likely very poor on account of limited resources and difficulties in providing them with skills which could lead to employability. While some among these in the census are students or draw a pension, the majority remain dependent on others.

Status of disabled non-workers

The majority of disabled non-workers are dependent on others, and most don't draw a pension. (Figures are as percentage of overall disabled population, those part of the work-force are not included).

|

|---|

| Above: Bar chart depicting categories of disabled population. |

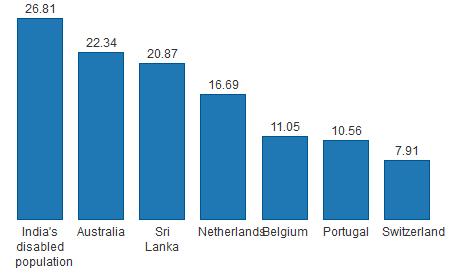

The need for greater attention and resources to this segment is clear from the fact that India’s disability numbers, even with the under-reporting, is higher than the population of entire nations.

Scale of the issue

India's disabled population is higher than the total populations of several countries, despite the under-reporting.Figure below shows India's disabled numbers, and total population (disabled + non-disabled) of other countries.

|

|---|

| Above: Bar chart depicting India's disabled numbers.

|

A 2007 World Bank report says that while India has one of the most progressive disability policy frameworks in the developing world—what with acts such as the Persons with Disabilities (Equal Opportunities, Protection of Rights and Full Participation) Act, 1995—implementation is poor. The report’s key recommendation is to “get the basics right”, especially identifying people with disabilities as soon as possible after onset. Almost a decade later, nothing seems to have changed.