BigDog is Watching You! The Sci-fi Future of Animal and Insect Drones

This research was undertaken as part of the 'SAFEGUARDS' project that CIS is undertaking with Privacy International and IDRC.

Just when we thought we had seen it all, the US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) funded another controversial surveillance project which makes even the most bizarre sci-fi movie seem like a pleasant fairy-tale in comparison to what we are facing: animal and insect drones.

Up until recently, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), otherwise called drones, depicted the scary reality of surveillance, as robotic pilot-less planes have been swarming the skies, while monitoring large amounts of data without people´s knowledge or consent. Today, DARPA has come up with more subtle forms of surveillance: animal and insect drones. Clearly animal and insect-like drones have a much better camouflage than aeroplanes, especially since they are able to go to places and obtain data that mainstream UAVs can not.

India´s ´DARPA´, the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), has been creating UAVs over the last ten years, while the Indian Army first acquired UAVs from Israel in the late 1990s. Yet the use of all UAVs in India is still poorly regulated! Drones in the U.S. are regulated by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), whilst the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) regulates drones in the European Union. In India, the Ministry of Civil Aviation regulates drones, whilst the government is moving ahead with plans to replace the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) with a Civil Aviation Authority. However, current Indian aviation laws are vague in regards to data acquired, shared and retained, thus not only posing a threat to individual´s right to privacy and other human rights, but also enabling the creation of a secret surveillance state.

The DRDO appears to be following DARPA´s footsteps in terms of surveillance technologies and the questions which arise are: will animal and insect drones be employed in India in the future? If so, how will they be regulated?

BigDog/LS3

Apparently having UAVs flying above us and monitoring territories and populations without our knowledge or consent was not enough. DARPA is currently funding the BigDog project, which is none other than a drone dog, a four-legged robot equipped with a camera and capable of surveillance in disguise. DARPA and Boston Dynamics are working on the latest version of BigDog, called the Legged Squad Support System (LS3), which can carry 400 pounds of gear for more than 20 miles without refuelling. Not only can the LS3 walk and run on all types of surfaces, including ice and snow, but it also has ´vision sensors´ which enable it to autonomously maneuver around obstacles and follow soldiers in the battle field. The LS3 is expected to respond to soldiers' voice commands, such as 'come', 'stop' and 'sit', as well as serve as a battery charger for electronic devices.

BigDog/LS3 is undoubtedly an impressive technological advancement in terms of aiding squads with surveillance, strategic management and a mobile auxiliary power source, as well as by carrying gear. Over the last century most technological developments have manifested through the military and have later been integrated in societies. Many questions arise around the BigDog/LS3 and its potential future use by governments for non-military purposes. Although UAVs were initially used for strictly military purposes, they are currently also being used by governments on an international level for civil purposes, such as to monitor climate change and extinct animals, as well as to surveille populations. Is it a matter of time before BigDog is used by governments for ´civil purposes´ too? Will robotic dogs swarm cities in the future to provide ´security´?

Like any other surveillance technology, the LS3 should be legally regulated and current lack of regulation could create a potential for abuse. Is authorisation required to use a LS3? If so, who has the legal right to authorise its use? Under what conditions can authorisation be granted and for how long? What kind of data can legally be obtained and under what conditions? Who has the legal authority to access such data? Can data be retained and if so, for how long and under what conditions? Do individuals have the right to be informed about the data withheld about them? Just because it´s a ´dog´ should not imply its non-regulation. This four-legged robot has extremely intrusive surveillance capabilities which may breach the right to privacy and other human rights when left unregulated.

Humming Bird Drone

|

|

|---|

| Source: HighTech Edge |

TIME magazine recognised DARPA for its Hummingbird nano air vehicle (NAV) and named the drone bird one of the 50 best inventions of 2011. True, it is rather impressive to create a robot which looks like a bird, behaves like a bird, but serves as a secret spy.

During the presentation of the humming bird drone, Regina Dugan, former Director of DARPA, stated:

"Since we took to the sky, we have wanted to fly faster and farther. And to do so, we've had to believe in impossible things and we've had to refuse to fear failure."

Although believing in 'impossible things' is usually a prerequisite to innovation, the potential implications on human rights of every innovation and their probability of occurring should be examined. Given the fact that drones already exist and that they are used for both military and non-military purposes, the probability is that the hummingbird drone will be used for civil purposes in the future. The value of data in contemporary information societies, as well as government's obsession with surveillance for ´national security´ purposes back up the probability that drone birds will not be restricted to battlefields.

So should innovation be encouraged for innovation’s sake, regardless of potential infringement of human rights? This question could open up a never-ending debate with supporters arguing that it´s not technology itself which is harmful, but its use or misuse. However the current reality of drones is this: UAVs and NAVs are poorly regulated (if regulated at all in many countries) and their potential for abuse is enormous, given that ´what happens to our data happens to ourselves....who controls our data controls our lives.´ If UAVs are used to surveille populations, why would drone birds not be used for the same purpose? In fact, they have an awesome camouflage and are potentially capable of acquiring much more data than any UAV! Given the surveillance benefits, governments would appear irrational not to use them.

MeshWorms and Remote-Controlled Insects

|

|---|

| Source: NY Daily News |

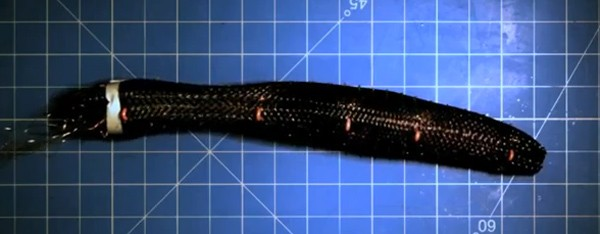

Think insects are creepy? Now we can have a real reason to be afraid of them. Clearly robotic planes, dogs and birds are not enough.

DARPA´s MeshWorm project entails the creation of earthworm-like robots that crawl along surfaces by contracting segments of their bodies. The MeshWorm can squeeze through tight spaces and mold its shape to rough terrain, as well as absorb heavy blows. This robotic worm will be used for military purposes, while future use for ´civil purposes´ remains a probability.

Robots, however, are not only the case. Actual insects are being wirelessly controlled, such as beetles with implanted electrodes and a radio receiver on their back. The giant flower beetle´s size enables it to carry a small camera and a heat sensor, which constitutes it as a reliable mean for surveillance.

Other drone insects look and fly like ladybugs and dragonflies. Researchers at the Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio, have been working on a butterfly drone since 2008. Former software engineer Alan Lovejoy has argued that the US is developing mosquito drones. Such a device could potentially be equipped with a camera and a microphone, it could use its needle to abstract a DNA sample with the pain of a mosquito bite and it could also inject a micro RFID tracking device under peoples´ skin. All such micro-drones could potentially be used for both military and civil purposes and could violate individuals´ right to privacy and other civil liberties.

Security vs. Privacy: The wrong debate

09/11 was not only a pioneering date for the U.S., but also for India and most countries in the world. The War on Terror unleashed a global wave of surveillance to supposedly enable the detection and prevention of crime and terrorism. Governments on an international level have been arguing over the last decade that the use of surveillance technologies is a prerequisite to safety. However, security expert, Bruce Schneier, argues that the trade-off of privacy for security is a false dichotomy.

Everyone can potentially be a suspect within a surveillance state. Analyses of Big Data can not only profile individuals and populations, but also identify ‘branches of communication’ around every individual. In short, if you know someone who may be considered a suspect by intelligence agencies, you may also be a suspect. The mainstream argument “I have nothing to hide, I am not a terrorist’ is none other than a psychological coping mechanism when dealing with surveillance. The reality of security indicates that when an individual’s data is being intercepted, the probability is that those who control that data can also control that individual’s life. Schneier has argued that privacy and security are not on the opposite side of a seesaw, but on the contrary, the one is a prerequisite of the other. Governments should not expect us to give up our privacy in exchange for security, as loss of privacy indicates loss of individuality and essentially, loss of freedom. We can not be safe when we trade-off our personal data, because privacy is what protects us from abuse from those in power. Thus the entire War on Terror appears to waged through a type of phishing, as the promise of ´security´ may be bait to acquire our personal data.

Since the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks, India has had more reasons to produce, buy and use surveillance technologies, including drones. Last New Year´s Eve, the Mumbai police used UAVs to monitor hotspots, supposedly to help track down revellers who sexually harass women. The Chennai police recently procured three UAVs from Anna University to assist them in keeping an eye on the city´s vehicle flow. Raj Thackeray´s rally marked the biggest surveillance exercise ever launched for a single event, which included UAVs. The Chandigarh police are the first Indian police force to use the ´Golden Hawk´ - a UAV which will keep a ´bird´s eye on criminal activities´. This new type of drone was manufactured by the Aeronautical Development Establishment (one of DRDO's premier laboratories based in Bangalore) and as of 2011 is being used by Indian law enforcement agencies.

Although there is no evidence that India currently has any animal or insect drones, it could be a probability in the forthcoming years. Since India is currently using many UAVs either way, why would animal and/or insect drones be excluded? What would prevent India from potentially using such drones in the future for ´civil purposes´? More importantly, how are ´civil purposes´ defined? Who defines ´civil purposes´and under what criteria? Would the term change and if so, under what circumstances? The term ´civil purposes´ varies from country to country and is defined by many political, social, economic and cultural factors, thus potentially enabling extensive surveillance and abuse of human rights.

Drones can potentially be as intrusive as other communications surveillance technologies, depending on the type of technology they´re equipped with, their location and the purpose of their use. As they can potentially violate individuals´ right to privacy, freedom of expression, freedom of movement and many other human rights, they should be strictly regulated. In Europe UAVs are regulated based upon their weight, as unmanned aircraft with an operating mass of less than 150kg are exempt by the EASA Regulation and its Implementation Rules. This should not be the case in India, as drones lighter than 150kg can potentially be more intrusive than other heavier drones, especially in the case of bird and insect drones.

Laws which explicitly regulate the use of all types of drones (UAVs, NAVs and micro-drones) and which legally define the term ´civil purposes´ in regards to human rights should be enacted in India. Some thoughts on the authorisation of drones include the following: A Special Committee on the Use of All Drones (SCUAD) could be established, which would be comprised of members of the jury, as well as by other legal and security experts of India. Such a committee would be the sole legal entity responsible for issuing authorisation for the use of drones, and every authorisation would have to comply with the constitutional and statutory provisions of human rights. Another committee, the Supervisory Committee on the Authorisation of the Use of Drones (lets call this ´SCAUD´), could also be established, which would also be comprised by (other) members of the jury, as well as by (other) legal and security experts of India. This second committee would supervise the first and it would ensure that SCUAD provides authorisations in compliance with the laws, once the necessity and utility of the use of drones has been adequately proven.

It´s not about ´privacy vs. security´. Nor is it about ´privacy or security´. In every democratic state, it should be about ´privacy and security´, since the one cannot exist without the other. Although the creation of animal and insect drones is undoubtedly technologically impressive, do we really want to live in a world where even animal-like robots can be used to spy on us? Should we be spied on at all? How much privacy do we give up and how much security do we gain in return through drones? If drones provided the ´promised security´, then India and all other countries equipped with these technologies should be extremely safe and crime-free; however, that is not the case.

In order to ensure that the use of drones does not infringe upon the right to privacy and other human rights, strict regulations are a minimal prerequisite. As long as people do not require that the use of these spying technologies are strictly regulated, very little can be done to prevent a scary sci-fi future. That´s why this blog has been written.