Enlarging the Small Print: A Study on Designing Effective Privacy Notices for Mobile Applications

Introduction: Ideas of Privacy and Consent Linked with Notices

The Notice and Choice Model

Most modern laws and data privacy principles seek to focus on individual control. As Alan Westin of Columbia University characterises privacy, "it is the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to other," [1] Or simply put, personal information privacy is "the ability of the individual to personally control information about himself."[2]

The preferred mechanism for protecting online privacy that has emerged is that of Notice and Choice.[3] The model, identified as "the most fundamental principle" in online privacy,[4] refers toconsumers consenting to privacy policies before availing of an online service. [5]

The following 3 standards of expectations of privacy in electronic communications have emerged in the United States courts:

- KATZ TEST: Katz v. United States,[6] a wiretap case, established expectation of privacy as one society is prepared to recognize as ―reasonable. [7]This concept is critical to a court's understanding of a new technology because there is no established precedent to guide its analysis[8]

- KYLLO/ KYLLO-KATZ HYBRID TEST: Society's reasonable expectation of privacy is higher when dealing with a new technology that is not ―generally available to the public.[9]This follows the logic that it is reasonable to expect common data collection practices to be used but not rare ones. [10] In Kyllo v. United States [11] law enforcement used a thermal imaging device to observe the relative heat levels inside a house. Though as per Katz the publicly available thermal radiation technology is reasonable, the uncommon means of collection was not. This modification to the Katz standard is extremely important in the context of mobile privacy. Mobile communications may be subdivided into smaller parts of audio from a phone call, e-mail, and data related to a user's current location. Following an application of the hybrid Katz/Kyllo test, the reasonable expectation of privacy in each of those communications would be determined separately[12], by evaluating the general accessibility of the technology required to capture each stream.[13]

- DOUBLE CLICK TEST: DoubleClick[14] illustrates the potential problems of transferring consent to a third party, one to whom the user never provided direct consent or is not even aware of. The court held that for DoubleClick, an online advertising network, to collect information from a user it needed only to obtain permission from the website that user accessed, and not from the user himself. The court reasoned that the information the user disclosed to the website was analogous to information one discloses to another person during a conversation. Just as the other party to the conversation would be free to tell his friends about anything that was said, a website should be free to disclose any information it receives from a user's visit after the user has consented to use the website's services.

These interpretations have weakened the standards of online privacy. While the Katz test vaguely hinges on societal expectations, the Kyllo Test to an extent strengthens privacy rights by disallowing uncommon methods of collection, but as the DoubleClick Test illustrates, once the user has consented to such practices he cannot object to the same. There have been sugestions to consider personal information as property when it shares features of property like location data.[15] It is fixed when it is in storage, it has a monetary value, and it is sold and traded on a regular basis. This would create a standard where consent is required for third-party access. [16] Consent will then play a more pivotal role in affixing liability.

The notice and choice mechanism is designed to put individuals in charge of the collection and use of their personal information. In theory, the regime preserves user autonomy by putting the individual in charge of decisions about the collection and use of personal information. [17] Notice and choice is asserted as a substitute for regulation because it is thought to be more flexible, inexpensive to implement, and easy to enforce.[18] Additionally, notice and choice can legitimize an information practice, whatever it may be, by obtaining an individual's consent and suit individual privacy preferences. [19]

However, the notice and choice mechanism is often criticized for leaving users uninformed-or misinformed, at least-as people rarely see, read, or understand privacy notices. [20] Moreover, few people opt out of the collection, use, or disclosure of their data when presented with the choice to do so.[21]

Amber Sinha of the Centre for Internet and Society argues that consent in these scenarios Is rarely meaningful as consumers fail to read/access privacy policies, understand the consequences and developers do not provide them the choice to opt out of a particular data practice while still being allowed to use their services. [22]

Of particular concern is the use of software applications (apps) designed to work on mobile devices. Estimates place the current number of apps available for download at more than 1.5 million, and that number is growing daily.[23] A 2011 Google study, "The Mobile Movement," identified that mobile devices are viewed as extensions of ourselves that we share with deeply personal relations with, raising fundamental questions of how apps and other mobile communications influence our privacy decision-making.

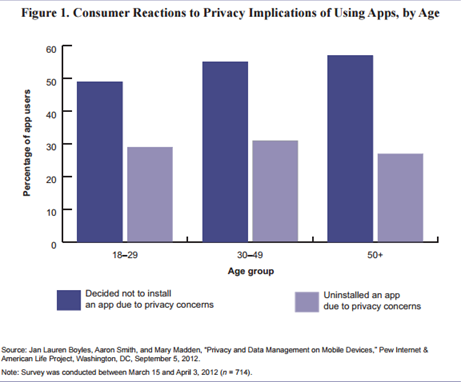

Recent research indicates that mobile device users have concerns about the privacy implications of using apps. [24] The research finds that almost 60 percent of respondents ages 50 and older decided not to install an app because of privacy concerns (see figure 1).[25]

Because no standards currently exist for providing privacy notice disclosure for apps, consumers may find it difficult to understand what data the app is collecting, how those data will be used, and what rights users have in limiting the collection and use of their data. Many apps do not provide users with privacy policy statements, making it impossible for app users to know the privacy implications of using a particular app. [26]Apps can make use of any or all of the device's functions, including contact lists, calendars, phone and messaging logs, locational information, Internet searches and usage, video and photo galleries, and other possibly sensitive information. For example, an app that allows the device to function as a scientific calculator may be accessing contact lists, locational data, and phone records even though such access is unnecessary for the app to function properly. [27]

Other apps may have privacy policies that are confusing or misleading. For example, an analysis of health and fitness apps found that more than 30 percent of the apps studied shared data with someone not disclosed in the app's privacy policy.[28]

Types of E-Contracts

Margaret Radin distinguishes two models of direct e-contracts based on consent as -"contract-as-consent" and "contract-as-product." [29]

The contract-as-consent model is the traditional picture of how binding commitment is arrived at between two humans. It involves a meeting of the minds which implies that terms be understood, alternatives be available, and probably that bargaining be possible.

In the contract-as-product model, the terms are part of the product, not a conceptually separate bargain; physical product plus terms are a package deal. For example the fact that a chip inside an electronics item will wear out after a year is an unseen contract creating a take-it-or-leave-it choice not to buy the package.

The product-as-consent model defies traditional ideas of consent and raises questions of whether consent is meaningful. Modern day e-contracts such as click wrap, shrink wrap, viral contracts and machine-made contracts which form the privacy policy of several apps have a product-as-consent approach where consumers are given the take-it-or-leave-it option.

Mobile application privacy notices fall into the product-as-consent model. Consumers often have to click "I agree" to all the innumerable Terms and Conditions in order to install the app. For instance terms that the fitness app will collect biometric data is a feature of the product that is non-negotiable. It is a classic take-it-or-leave-it approach where consumers compromise on privacy to avail services.

Contracts that facilitate these transactions are generally long and complicated and often agreed to by consumers without reading them.

Craswell strikes a balance in applying the liability rule to point out that as explaining the meaning of extensive fine print would be very costly to point out it could be efficient to affix the liability rule not as a written contract but rather on "reasonable" terms. This means that if a fitness app collects sensitive financial information, which is unreasonable given its core activities, then even if the user has consented to the same in the privacy policy's fine print the contract should be capable of being challenged.

The Concept of Privacy by Design

Privacy needs to be considered from the very beginning of system development. For this reason, Dr. Anne Cavoukian [30] coined the term "Privacy by Design", that is, privacy should be taken into account throughout the entire engineering process from the earliest design stages to the operation of the productive system. This holistic approach is promising, but it does not come with mechanisms to integrate privacy in the development processes of a system. The privacy-by-design approach, i.e. that data protection safeguards should be built into products and services from the earliest stage of development, has been addressed by the European Commission in their proposal for a General Data Protection Regulation. This proposal uses the terms "privacy by design" and "data protection by design" synonymously.

The 7 Foundational Principles[31] of Privacy by Design are:

- Proactive not Reactive; Preventative not Remedial

- Privacy as the Default Setting

- Privacy Embedded into Design

- Full Functionality - Positive-Sum, not Zero-Sum

- End-to-End Security - Full Lifecycle Protection

- Visibility and Transparency - Keep it Open

- Respect for User Privacy - Keep it User-Centric

Several terms have been introduced to describe types of data that need to be protected. A term very prominently used by industry is "personally identifiable information (PII)", i.e., data that can be related to an individual. Similarly, the European data protection framework centres on "personal data". However, some authors argue that this falls short since also data that is not related to a single individual might still have an impact on the privacy of groups, e.g., an entire group might be discriminated with the help of certain information. For data of this category the term "privacy-relevant data" has been used. [32]

An essential part of Privacy by Design is that data subjects should be adequately informed whenever personal data is processed. Whenever data subjects use a system, they should be informed about which information is processed, for what purpose, by which means and who it is shared is with. They should be informed about their data access rights and how to exercise them.[33]

Whereas system design very often does not or barely consider the end-users' interests, but primarily focuses on owners and operators of the system, it is essential to account the privacy and security interests of all parties involved by informing them about associated advantages (e.g. security gains) and disadvantages (e.g. costs, use of resources, less personalisation). By creating this system of "multilateral security" the demands of all parties must be realized.[34]

The Concept of Data Minimization

The most basic privacy design strategy is MINIMISE, which states that the amount of personal data that is processed should be restricted to the minimal amount possible. By ensuring that no, or no unnecessary, data is collected, the possible privacy impact of a system is limited. Applying the MINIMISE strategy means one has to answer whether the processing of personal data is proportional (with respect to the purpose) and whether no other, less invasive, means exist to achieve the same purpose. The decision to collect personal data can be made at design time and at run time, and can take various forms. For example, one can decide not to collect any information about a particular data subject at all. Alternatively, one can decide to collect only a limited set of attributes.[35]

If a company collects and retains large amounts of data, there is an increased risk that the data will be used in a way that departs from consumers' reasonable expectations.[36]

There are three privacy protection goals[37] that data minimization and privacy by design seek to achieve. These privacy protection goals are:

- Unlinkability - To prevent data being linked to an identifiable entity

- Transparency - The information has to be available before, during and after the processing takes place.

- Intervenability - Those who provide their data must have means of intervention into all ongoing or planned privacy-relevant data processing

Spiekermann and Cranor raised an intriguing point in their paper, they argued that those companies that employ privacy by design and data minimization practices in their applications should be allowed to skip the need for privacy policies and forgo need for notice and choice features. [38]

|

To Summarise: The emerging model and legal dialogue that regulates online privacy is that of Notice and Choice which has been severely criticised for not creating informed choice making processes. E-contracts such as agreeing to privacy notices follow the consent-as-product model. When there is extensive fine print liability must be affixed on the basis of reasonable terms. Privacy notices must incorporate the concepts of Privacy by Design through providing complete information and collecting minimum data.

|

Features of Privacy Notices in the Current Mobile Ecosystem

A privacy notice inform a system's users or a company's customers of data practices involving personal information. Internal practices with regard to the collection, processing, retention, and sharing of personal information should be made transparent.

Each app a user chooses to install on his smartphone can access different information stored on that device. There is no automatic access to user information. Each application has access only to the data that it pulls into its own 'sandbox'.

The sandbox is a set of fine-grained controls limiting an application's access to files, preferences, network resources, hardware etc. Applications cannot access each other's sandboxes.[39] The data that makes it into the sandbox is normally defined by user permissions.[40] These are a set of user defined controls[41]and evidence that a user consents to the application accessing that data. [42]

To gain permission mobile apps generally display privacy notices that explicitly seek consent. These can leverage different channels, including a privacy policy document posted on a website or linked to from mobile app stores or mobile apps. For example, Google Maps uses a traditional clickwrap structure that requires the user to agree to a list of terms and conditions when the program is initially launched. [43] Foursquare, on the other hand, embeds its terms in a privacy policy posted on its website, and not within the app. [44]

This section explains the features of current privacy notices on the 4 parameters of stage (at which the notice is given), content, length and user comprehension. Under each of these parameters the associated problems are identified and alternatives are suggested.

(1) Timing and Frequency of Notice:

This sub-section identifies the various stages that notices are given and highlights their advantages, disadvantages and makes recommendations. It concludes with the findings of a study on what the ideal stage to provide notice is. This is supplemented with 2 critical models to address the common problems of habituation and contextualization.

Studies indicate that timing of notices or the stage at which they are given impact how consumer's recall and comprehend them and make choices accordingly. [45] I ntroducing only a 15-second delay between the presentation of privacy notices and privacy relevant choices can be enough to render notices ineffective at driving user behaviour.[46]

Google Android and Apple iOS provide notices at different times. At the time of writing, Android users are shown a list of requested permissions while the app is being installed, i.e., after the user has chosen to install the app. In contrast, iOS shows a dialog during app use, the first time a permission is requested by an app. This is also referred to as a "just-in-time" notification. [47]

The following are the stages in which a notice can be given:

1) NOTICE AT SETUP: Notice can be provided when a system is used for the first time[48]. For instance, as part of a software installation process users are shown and have to accept the system's terms of use.

a) Advantages: Users can inspect a system's data practices before using or purchasing it. The system developer is benefitted due to liability and transparency reasons that gain user trust. It provides the opportunity to explain unexpected data practices that may have a benign purpose in the context of the system[49]. It can even impact purchase decisions. Egelman et al. found that participants were more likely to pay a premium at a privacy-protective website when they saw privacy information in search results, as opposed to on the website after selecting a search result[50].

b) Disadvantages: Users have become largely habituated to install time notices and ignore them[51]. Users may have difficulty making informed decisions because they have not used the system yet and cannot fully assess its utility or weigh privacy trade-offs. They may also be focused on the primary task, namely completing the setup process to be able to use the system, and fail to pay attention to notices [52].

c) Recommendations: Privacy notices provided at setup time should be concise and focus on data practices immediately relevant to the primary user rather than presenting extensive terms of service. Integrating privacy information into other materials that explain the functionality of the system may further increase the chance that users do not ignore it.[53]

2) JUST IN TIME NOTICE: A privacy notice can be shown when a data practice is active, for example when information is being collected, used, or shared. Such notices are referred to as "contextualized" or "just-in-time" notices[54].

a) Advantages: They enhance transparency and enable users to make privacy decisions in context. Users have also been shown to more freely share information if they are given relevant explanations at the time of data collection[55].

b) Disadvantages: Habituation can occur if these are shown too frequently. Moreover in apps such as gaming apps users generally tend to ignore notices displayed during usage.

c) Recommendations: Consumers can be given notice the first time a particular type of information is accessed such as email and then be given the option to opt out of further notifications. A Consumer may then seek to opt out of notices on email but choose to view all notices on health information that is accessed depending on his privacy priorities.

3) CONTEXT-DEPENDENT NOTICES: The user's and system's context can also be considered to show additional notices or controls if deemed necessary [56]. Relevant context may be determined by a change of location, additional users included in or receiving the data, and other situational parameters. Some locations may be particularly sensitive, therefore users may appreciate being reminded that they are sharing their location when they are in a new place, or when they are sharing other information that may be sensitive in a specific context. Facebook introduced a privacy checkup message in 2014 that is displayed under certain conditions before posting publicly. It acts as a "nudge" [57] to make users aware that the post will be public and to help them manage who can see their posts.

a) Advantages: It may help users make privacy decisions that are more aligned with their desired level of privacy in the respective situation and thus foster trust in the system.

b) Disadvantages: Challenges in providing context-dependent notices are detecting relevant situations and context changes. Furthermore, determining whether a context is relevant to an individual's privacy concerns could in itself require access to that person's sensitive data and privacy preferences. [58]

c) Recommendations: Standards must be evolved to determine a contextual model based on user preferences.

4) PERIODIC NOTICES: These are shown the first couple of times a data practice occurs, or every time. The sensitivity of the data practice may determine the appropriate frequency.

a) Advantages: It can further help users maintain awareness of privacy-sensitive information flows especially when data practices are largely invisible [59]such as in patient monitoring apps. This helps provide better control options.

b) Disadvantages: Repeating notices can lead to notice fatigue and habituation[60].

c) Recommendations: Frequency of these notices needs to be balanced with user needs. [61] Data practices that are reasonably expected as part of the system may require only a single notice, whereas practices falling outside the expected context of use which the user is potentially unaware of may warrant repeated notices. Periodic notices should be relevant to users in order to be not perceived as annoying. A combined notice can remind about multiple ongoing data practices. Rotating warnings or changing their look can also further reduce habituation effects [62]

5) PERSISTENT NOTICES: A persistent indicator is typically non-blocking and may be shown whenever a data practices is active, for instance when information is being collected continuously or when information is being transmitted[63]. When inactive or not shown, persistent notices also indicate that the respective data practice is currently not active. For instance, Android and iOS display a small icon in the status bar whenever an application accesses the user's location.

a) Advantages: These are easy to understand and not annoying increasing their functionality.

b) Disadvantages: These ambient indicators often go unnoticed.[64] Most systems can only accommodate such indicators for a small number of data practices.

c) Recommendations: Persistent indicators should be designed to be noticeable when they are active. A system should only provide a small set of persistent indicators to indicate activity of especially critical data practices which the user can also specify.

6) NOTICE ON DEMAND: Users may also actively seek privacy information and request a privacy notice. A typical example is posting a privacy policy at a persistent location[65] and providing links to it from the app. [66]

a) Advantages: Privacy sensitive users are given the option to better explore policies and make informed decisions.

b) Disadvantages: The current model of a link to a long privacy policy on a website will discourage users from requesting for information that they cannot fully understand and do not have time to read.

c) Recommendations: Better option are privacy settings interfaces or privacy dashboards within the system that provide information about data practices; controls to manage consent; summary reports of what information has been collected, used, and shared by the system; as well as options to manage or delete collected information. Contact information for a privacy office should be provided to enable users to make written requests.

Which of these Stages is the Most Ideal?

In a series of experiments, Rebecca Balekabo and others [67] have identified the impact of timing on smartphone privacy notices. The following 5 conditions were imposed on participants who were later tested on their levels of recall of the notices through questions:

- Not Shown: The participants installed and used the app without being shown a privacy notice

- App Store: Notice was shown at the time of installation at the app store

- App store Big: A large notice occupying more screen space was shown at the app store

- App Store Popup: A smaller popup was displayed at the app Store

- During use: Notice was shown during usage of the app

The results (Figure) suggest that even if a notice contains information users care about, it is unlikely to be recalled if only shown in the app store and more effective when shown during app usage.

Seeing the app notice during app usage resulted in better recall. Although participants remembered the notice shown after app use as well as in other points of app use, they found that it was not a good point for them to make decisions about the app because they had already used it, and participants preferred when the notice was shown during or before app usage.

Hence depending on the app there are optimal times to show smartphone privacy notices to maximize attention and recall with preference being given to the beginning of or during app use.

However several of these stages as outlined baove face the disadvantages of habituation and uncertainty on contextualization. The following 2 models have been proposed to address this:

Habituation

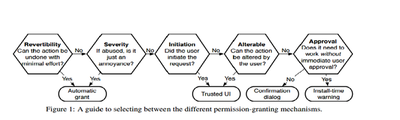

When notices are shown too frequently, users may become habituated. Habituation may lead to users disregarding warnings, often without reading or comprehending the notice[68]. To reduce habituation from app permission notices, Felt et al. identified a tested method to determine which permission requests should be emphasized [69]

They categorized actions on the basis of revertibility, severability, initiation, alterable and approval nature (Explained in figure) and applied the following permission granting mechanisms :

- Automatic Grant: It must be requested by the developer, but it is granted without user involvement.

- Trusted UI elements: They appear as part of an application's workflow, but clicking on them imbues the application with a new permission. To ensure that applications cannot trick users, trusted UI elements can be controlled only by the platform. For example, a user who is sending an SMS message from a third-party application will ultimately need to press a button; using trusted UI means the platform provides the button.

- Confirmation Dialog: Runtime consent dialogs interrupt the user's flow by prompting them to allow or deny a permission and often contain descriptions of the risk or an option to remember the decision.

- Install-time warning: These integrate permission granting into the installation flow. Installation screens list the application's requested permissions. In some platforms (e.g., Facebook), the user can reject some install-time permissions. In other platforms (e.g., Android and Windows 8 Metro), the user must approve all requested permissions or abort installation.[70]

Based on these conditions the following sequential model that the system must adopt was proposed to determine frequency of displaying notices:

Initial tests have proven to be successful in reducing habituation effects and it is an important step towards designing and displaying privacy notices.

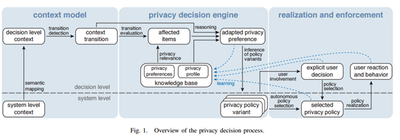

Contextualization

Bastian Koning and others, in their paper "Towards Context Adaptive Privacy Decisions in Ubiquitous Computing" [71] propose a system for supporting a user's privacy decisions in situ, i.e., in the context they are required in, following the notion of contextual integrity. It approximates the user's privacy preferences and adapts them to the current context. The system can then either recommend sharing decisions and actions or autonomously reconfigure privacy settings. It is divided into the following stages:

Context Model: A distinction is created between the decision level and system level. The system level enables context awareness but also filters context information and maps it to semantic concepts required for decisions. Semantic mappings can be derived from a pre-defined or learnt world model. On the decision level, the context model only contains components relevant for privacy decision making. For example: An activity involves the user, is assigned a type, i.e., a semantic label, such as home or work, based on system level input.

Privacy Decision Engine : The context model allows to reason about which context items are affected by a context transition. When a transition occurs, the privacy decision engine (PDE) evaluates which protection worthy context items are affected. Protection worthiness (or privacy relevance) of context items for a given context are determined by the user's privacy preferences that are This serves as a basis for adapting privacy preferences and is subsequently further adjusted to the user by learning from the user's explicit decisions, behaviour, and reaction to system actions. [72] approximated by the system from the knowledge base.

The user's personality type is determined before initial system use to select a basic privacy profile.

It may also be possible that the privacy preference cannot be realized in the current context. In that case, the privacy policy would suggest terminating the activity. For each privacy policy variant a confidence score is calculated based on how well it fits the adapted privacy preference. Based on the confidence scores, the PDE selects the most appropriate policy candidate or triggers user involvement if the confidence is below a certain threshold determined by the user's personality and previous privacy decisions.

Realization and Enforcement: The selected privacy policy must be realized on the system level. This is by combining territorial privacy and information privacy aspects. The private territory is defined by a territorial privacy boundary that separates desired and undesired entities.

Granularity adjustments for specific Information items is defined. For example, instead of the user's exact position only the street address or city can be provided.

ADVANTAGES: The personalization to a specific user has the advantage of better emulating that user's privacy decision process. It also helps to decide when to involve the user in the decision process by providing recommendations only and when privacy decisions can be realized autonomously.

DISADVANTAGES: The entire model hinges on the ability of the system to accurately determine user profile before the user starts using it and not after, when preferences can be more accurately determined. There is no provision for the user to pick his own privacy profile, it is all system determined taking away an element of consent in the very beginning. As all further preferences are adapted on this base, it is possible that the system may not deliver. The use of confident scores is an approximation that can compromise privacy by a small numerical margin of difference.

However it is a useful insight on techniques of contextualization. Depending on the environment, different strategies for policy realization and varying degrees of enforcement are possible[73].

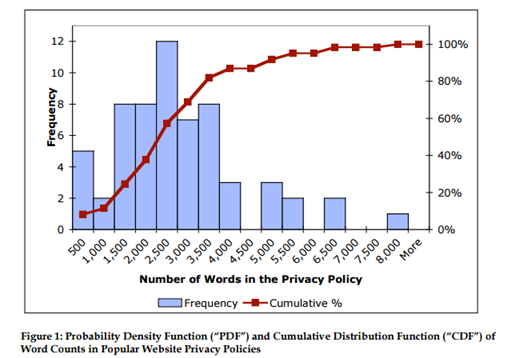

Length

The length of privacy policies is often cited as one reason they are so commonly ignored. Studies show privacy policies are hard to read, read infrequently, and do not support rational decision making. [74] Aleecia M. McDonald and Lorrie Faith Cranor in their seminal study, "The Cost of Reading Privacy Policies" estimated that the the average length of privacy policies is 2,500 words. Using the reading speed of 250 words per minute which is typical for those who have completed secondary education, the average policy would take 10 minutes to read.

The researchers also investigated how quickly people could read privacy policies when they were just skimming it for pertinent details. They timed 93 people as they skimmed a 934-word privacy policy and answered multiple choice questions on its content.

Though some people took under a minute and others up to 42 minutes, the bulk of the subjects of the research took between three and six minutes to skim the policy, which itself was just over a third of the size of the average policy.

The researchers used their data to estimate how much it costs to read the privacy policy of every site they visit once a year if their time was charged for and arrived at a mind boggling figure of $652 billion.

Problems

Though the figure of $652 billion has limited usefulness, because people rarely read whole policies and cannot charge anyone for the time it takes to do this, the researchers concluded that readers who do conduct a cost-benefit analysis might decide not to read any policies.

"Preliminary work from a small pilot study in our laboratory revealed that some Internet users believe their only serious risk online is they may lose up to $50 if their credit card information is stolen. For people who think that is their primary risk, our point estimates show the value of their time to read policies far exceeds this risk. Even for our lower bound estimates of the value of time, it is not worth reading privacy policies though it may be worth skimming them," said the research. This implies that seeing their only risk as credit card fraud suggests Internet users likely do not understand the risks to their privacy. As an FTC report recently stated, "it is unclear whether consumers even understand that their information is being collected, aggregated, and used to deliver advertising."[75]"

Recommendations

If the privacy community can find ways to reduce the time cost of reading policies, it may be easier to convince Internet users to do so. For example, if consumers can move from needing to read policies word-for-word and only skim policies by providing useful headings, or with ways to hide all but relevant information in a layered format and thus reduce the effective length of the policies, more people may be willing to read them. [76] Apps can also adopt short form notices that summarize and link to the larger more complete notice displayed elsewhere. These short form notices need not be legally binding and must candidate that it does not cover all types of data collection but only the most relevant ones. [77]

Content

In an attempt to gain permission most privacy policies inform users about: (1) the type of information collected; and (2) the purpose for collecting that information.

Standard privacy notices generally cover the points of:

- Methods Of Collection And Usage Of Personal Information

- The Cookie Policy

- Sharing Of Customer Information [78]

Certified Information Privacy Professionals divide notices into the following sequential sections[79]:

i. Policy Identification Details: Defines the policy name, version and description.

ii. P3P-Based Components: Defines policy attributes that would apply if the policy is exported to a P3P format. [80] Such attributes would include: policy URLs, organization information, PII access and dispute resolution procedures.

iii. Policy Statements and Related Elements: Groups, Purposes and PII Types-Policy statements define the individuals able to access certain types of information, for certain pre-defined purposes.

Problems

Applications tend to define the type of data broadly in an attempt to strike a balance between providing enough information so that application may gain consent to access a user's data and being broad enough to avoid ruling out specific information.[81]

This leads to usage of vague terms like "information collected may include."[82]

Similarly the purpose of the data acquisition is also very broad. For example, a privacy policy may state that user data can be collected for anything related to ―"improving the content of the Service." As the scope of ―improving the content of the Service is never defined, any usage could conceivably fall within that category.[83]

Several apps create user social profiles based on their online preferences to promote targeted marketing which is cleverly concealed in phrases like "we may also draw upon this Personal Information in order to adapt the Services of our community to your needs". [84] For instance Bees & Pollen is a "predictive personalization" platform for games and apps that "uses advanced predictive algorithms to detect complex, non-trivial correlations between conversion patterns and users' DNA signatures, thus enabling it to automatically serve each user a personalized best-fit game options, in real-time." In reality it analyses over 100 user attributes, including activity on Facebook, spending behaviours, marital status, and location.[85]

Notices also often mislead consumers into believing that their information will not be shared with third parties using the terms "unaffiliated third parties." Other affiliated companies within the corporate structure of the service provider may have access to user's data for marketing and other purposes. [86]

There are very few choices to opt-out of certain practices, such as sharing data for marketing purposes. Thus, users are effectively left with a take-it-or-leave-it choice - give up your privacy or go elsewhere.[87]Users almost always grant consent if it is required to receive the service they want which raises the query if this consent is meaningful[88].

Recommendations

The following recommendations have emerged:

- Notice - Companies should provide consumers with clear, conspicuous notice that accurately describe their information practices.

- Consumer Choice - Companies should provide consumers with the opportunity to decide (in the form of opting-out) if it may disclose personal information to unaffiliated third parties.

- Access and Correction - Companies should provide consumers with the opportunity to access and correct personal information collected about the consumer.

- Security - Companies must adopt reasonable security measures in order to protect the privacy of personal information. Possible security measures include: administrative security, physical security and technical security.

- Enforcement - Companies should have systems through which they can enforce the privacy policy. This may be managed by the company, or an independent third party to ensure compliance. Examples of popular third parties include BBBOnLine and TRUSTe.[89]

- Standardization : Several researchers and organizations have recommended a standardized privacy notice format that covers certain essential points. [90] However as displaying a privacy notice in itself is voluntary it is unpredictable whether companies would willingly adopt a standardized model. Moreover with the app market burgeoning with innovations a standard format may not cover all emergent data practices.

Comprehension

The FTC states that "the notice-and-choice model, as implemented, has led to long, incomprehensible privacy policies that consumers typically do not read, let alone understand. the question is not whether consumers should be given a say over unexpected uses of their data; rather, the question is how to provide simplified notice and choice"[91].

Notably, in a survey conducted by Zogby International, 93% of adults - and 81% of teens - indicated they would take more time to read terms and conditions for websites if they were written in clearer language.[92]

Most privacy policies are in natural language format: companies explain their practices in prose. One noted disadvantage to current natural language policies is that companies can choose which information to present, which does not necessarily solve the problem of information asymmetry between companies and consumers. Further, companies use what have been termed "weasel words" - legalistic, ambiguous, or slanted phrases - to describe their practices [93].

In a study by Aleecia M. McDonald and others[94], it was found that accuracy in what users comprehend span a wide range. An average of 91% of participants answered correctly when asked about cookies, 61% answered correctly about opt out links, 60% understood when their email address would be "shared" with a third party, and only 46% answered correctly regarding telemarketing. Participants found those questions harder which substituted vague or complicated terms to refer to practices such as telemarketing by "the information you provide may be used for marketing services." Overall accuracy was a mere 33%.

Problems

Natural language policies are often long and require college-level reading skills. Furthermore, there are no standards for which information is disclosed, no standard place to find particular information, and data practices are not described using consistent language. These policies are "long, complicated, and full of jargon and change frequently."[95]

Kent Walker list five problems that privacy notices typically suffer from -

a) overkill - long and repetitive text in small print,

b) irrelevance - describing situations of little concern to most consumers,

c) opacity - broad terms the reflect the truth that is impossible to track and control all the information collected and stored,

d) non-comparability - simplification required to achieve comparability will lead to compromising accuracy, and

e) inflexibility - failure to keep pace with new business models. [96]

Recommendations

Researchers advocate a more succinct and simpler standard for privacy notices,[97] such as representing the information in the form of a table. [98] However, studies show only an insignificant improvement in the understanding by consumers when privacy policies are represented in graphic formats like tables and labels. [99]

There are also recommendations to adopt a multi-layered approach where the relevant information is summarized through a short notice.[100] This is backed by studies that consumers find layered policies easier to understand. [101] However they were less accurate in the layered format especially with parts that were not summarized. This suggests participants that did not continue to the full policy when the information they sought was not available on the short notice. Unless it is possible to identify all of the topics users care about and summarize to one page, the layered notice effectively hides information and reduces transparency. It has also been pointed out that it is impossible to convey complex data policies in simple and clear language. [102]

Consumers often struggle to map concepts such as third party access to the terms used in policies. This is also because companies with identical practices often convey different information, and these differences reflected in consumer's ability to understand the policies. These policies may need an educational component so readers understand what it means for a site to engage in a given practice[103]. However it is unlikely that when readers fail to take time to read the policy that they will read up on additional educational components.

[1] Amber Sinha http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/a-critique-of-consent-in-information-privacy

[2] Wang, et al., 1998) Milberg, et al. (1995)

[3] See e.g., White House, Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights (2012) http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-pressoffice/2012/02/23/we-can-t-wait-obama-administration-unveils-blueprint-privacy-bill-rights; Fed. Trade Comm'n, Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change: Recommendations for Business and Policy Makers (2012) http://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commissionreport-protecting-consumer-privacy-era-rapid-change-recommendations/120326privacyreport.pdf.

[4] Fed. Trade Comm'n, Privacy Online: A Report to Congress 7 (June 1998), available at www.ftc.gov/reports/privacy3/priv-23a.pdf.

[5] U.S. Department of Commerce , Internet Policy Task Force, Commercial Data Privacy and Innovation in the Internet Economy: A Dynamic Policy Framework 20 (Dec. 16, 2010) (full-text).

[6] 389 U.S. 347 (1967).

[7] Dow Chem. Co. v. United States, 476 U.S. 227, 241 (1986)

[8] http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1600&context=iplj

[9] Dow Chem. Co. v. United States, 476 U.S. 227, 241 (1986)

[10] Kyllo, 533 U.S. at 34 (―[T]he technology enabling human flight has exposed to public view (and hence, we have said, to official observation) uncovered portions of the house and its curtilage that once were private.‖).

[11] Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27

[12] See Katz, 389 U.S. at 352 (―But what he sought to exclude when he entered the booth was not the intruding eye-it was the uninvited ear. He did not shed his right to do so simply because he made his calls from a place where he might be seen.‖).

[13] See United States v. Ahrndt, No. 08-468-KI, 2010 WL 3773994, at *4 (D. Or. Jan. 8, 2010).

[14] In re DoubleClick Inc. Privacy Litig., 154 F. Supp. 2d 497 (S.D.N.Y. 2001).

[15] http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1600&context=iplj

[16] See Michael A. Carrier, Against Cyberproperty, 22 BERKELEY TECH. L.J. 1485, 1486 (2007) (arguing against creating a right to exclude users from making electronic contact to their network as one that exceeds traditional property notions).

[17] See M. Ryan Calo, Against Notice Skepticism in Privacy (and Elsewhere), 87 NOTRE DAME L. REV. 1027, 1049 (2012) (citing Paula J. Dalley, The Use and Misuse of Disclosure as a Regulatory System, 34 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 1089, 1093 (2007) ("[D]isclosure schemes comport with the prevailing political philosophy in that disclosure preserves individual choice while avoiding direct governmental interference.")).

[18] See Calo, supra note 10, at 1048; see also Omri Ben-Shahar & Carl E. Schneider, The Failure of Mandated Disclosure, 159 U. PA. L. REV. 647, 682 (noting that notice "looks cheap" and "looks easy").

[19] Mark MacCarthy, New Directions in Privacy: Disclosure, Unfairness and Externalities, 6 I/S J. L. & POL'Y FOR INFO. SOC'Y 425, 440 (2011) (citing M. Ryan Calo, A Hybrid Conception of Privacy Harm Draft-Privacy Law Scholars Conference 2010, p. 28).

[20] Daniel J. Solove, Introduction: Privacy Self-Management and the Consent Dilemma, 126 HARV. L. REV. 1879, 1885 (2013) (citing Jon Leibowitz, Fed. Trade Comm'n, So Private, So Public: Individuals, the Internet & the Paradox of Behavioral Marketing, Remarks at the FTC Town Hall Meeting on Behavioral Advertising: Tracking, Targeting, & Technology (Nov. 1, 2007), available at http://www.ftc.gov/speeches/leibowitz/071031ehavior/pdf). Paul Ohm refers to these issues as "information-quality problems." See Paul Ohm, Branding Privacy, 97 MINN. L. REV. 907, 930 (2013). Daniel J. Solove refers to this as "the problem of the uninformed individual." See Solove, supra note 17

[21] See Edward J. Janger & Paul M. Schwartz, The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, Information Privacy, and the Limits of Default Rules, 86 MINN. L. REV. 1219, 1230 (2002) (stating that according to one survey, "only 0.5% of banking customers had exercised their opt-out rights").

[22] See Amber Sinha A Critique of Consent in Information Privacy http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/a-critique-of-consent-in-information-privacy

[23] Leigh Shevchik, "Mobile App Industry to Reach Record Revenue in 2013," New Relic (blog), April 1, 2013, http://blog.newrelic.com/2013/04/01/mobile-apps-industry-to-reach-record-revenue-in-2013/.

[24] Jan Lauren Boyles, Aaron Smith, and Mary Madden, "Privacy and Data Management on Mobile Devices," Pew Internet & American Life Project, Washington, DC, September 5, 2012.

[25] http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/cons_prot/2014/improving-mobile-device-privacy-disclosures-AARP-ppi-cons-prot.pdf

[26] "Mobile Apps for Kids: Disclosures Still Not Making the Grade," Federal Trade Commission, Washington, DC, December 2012

[27] http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/cons_prot/2014/improving-mobile-device-privacy-disclosures-AARP-ppi-cons-prot.pdf

[28] Linda Ackerman, "Mobile Health and Fitness Applications and Information Privacy," Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, San Diego, CA, July 15, 2013.

[29] Margaret Jane Radin, Humans, Computers, and Binding Commitment, 75 IND. L.J. 1125, 1126 (1999). http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2199&context=ilj

[30] William Aiello, Steven M. Bellovin, Matt Blaze, Ran Canetti, John Ioannidis, Angelos D. Keromytis, and Omer Reingold. Just fast keying: Key agreement in a hostile internet. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur., 7(2):242-273, 2004.

[31] Privacy By Design The 7 Foundational Principles by Anne Cavoukian https://www.ipc.on.ca/images/resources/7foundationalprinciples.pdf

[32] G. Danezis, J. Domingo-Ferrer, M. Hansen, J.-H. Hoepman, D. Le M´etayer, R. Tirtea, and S. Schiffner. Privacy and Data Protection by Design - from policy to engineering. report, ENISA, Dec. 2014.

[33] G. Danezis, J. Domingo-Ferrer, M. Hansen, J.-H. Hoepman, D. Le M´etayer, R. Tirtea, and S. Schiffner. Privacy and Data Protection by Design - from policy to engineering. report, ENISA, Dec. 2014.

[34] G. Danezis, J. Domingo-Ferrer, M. Hansen, J.-H. Hoepman, D. Le M´etayer, R. Tirtea, and S. Schiffner. Privacy and Data Protection by Design - from policy to engineering. report, ENISA, Dec. 2014.

[35] John Frank Weaver, We Need to Pass Legislation on Artificial Intelligence Early and Often, SLATE FUTURE TENSE (Sept. 12, 2014),http://www.slate.com/blogs/future_tense/2014/09/12/we_need_to_pass_artificial_intelligence_laws_early_and_often.html

[36] Margaret Jane Radin, Humans, Computers, and Binding Commitment, 75 IND. L.J. 1125, 1126 (1999).

[37] Richard Warner & Robert Sloan, Beyond Notice and Choice: Privacy, Norms, and Consent, J. High Tech. L. (2013). Available at: http://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/fac_schol/568

[39] iOS Application Programming Guide: The Application Runtime Environment, APPLE, http://developer.apple.com/library/ ios/#documentation/iphone/conceptual/iphoneosprogrammingguide/RuntimeEnvironment /RuntimeEnvironment.html (last updated Feb. 24, 2011)

[40] Security and Permissions, ANDROID DEVELOPERS, http://developer.android.com/guide/topics/security/security.html (last updated Sept. 13, 2011).

[41] iOS Application Programming Guide: The Application Runtime Environment, APPLE, http://developer.apple.com/library/ ios/#documentation/iphone/conceptual/iphoneosprogrammingguide/RuntimeEnvironment /RuntimeEnvironment.html (last updated Feb. 24, 2011)

[42] See Katherine Noyes, Why Android App Security is Better Than for the iPhone, PC WORLD BUS. CTR. (Aug. 6, 2010, 4:20 PM), http://www.pcworld.com/businesscenter/article/202758/why_android_app_security_is_be tter_than_for_the_iphone.html; see also About Permissions for Third-Party Applications, BLACKBERRY, http://docs.blackberry.com/en/smartphone_users/deliverables/22178/ About_permissions_for_third-party_apps_50_778147_11.jsp (last visited Sept. 29, 2011); Security and Permissions, supra note 76.

[43] Peter S. Vogel, A Worrisome Truth: Internet Privacy is Impossible, TECHNEWSWORLD (June 8, 2011, 5:00 AM), http://www.technewsworld.com/ story/72610.html.

[44] Privacy Policy, FOURSQUARE, http://foursquare.com/legal/privacy (last updated Jan. 12, 2011)

[45] N. S. Good, J. Grossklags, D. K. Mulligan, and J. A. Konstan. Noticing Notice: A Large-scale Experiment on the Timing of Software License Agreements. In Proc. of CHI. ACM, 2007.

[46] I. Adjerid, A. Acquisti, L. Brandimarte, and G. Loewenstein. Sleights of Privacy: Framing, Disclosures, and the Limits of Transparency. In Proc. of SOUPS. ACM, 2013.

[47] http://delivery.acm.org/10.1145/2810000/2808119/p63-balebako.pdf?ip=106.51.36.200&id=2808119&acc=OA&key=4D4702B0C3E38B35%2E4D4702B0C3E38B35%2E4D4702B0C3E38B35%2E35B5BCE80D07AAD9&CFID=801296199&CFTOKEN=33661544&__acm__=1466052980_2f265a2442ea3394aa1ebab7e6449933

[48] Microsoft. Privacy Guidelines for Developing Software Products and Services. Technical Report version 3.1, 2008.

[49] Microsoft. Privacy Guidelines for Developing Software Products and Services. Technical Report version 3.1, 2008.

[50] S. Egelman, J. Tsai, L. F. Cranor, and A. Acquisti. Timing is everything?: the effects of timing and placement of online privacy indicators. In Proc. CHI '09. ACM, 2009.

[51] R. B¨ohme and S. K¨opsell. Trained to accept?: A field experiment on consent dialogs. In Proc. CHI '10. ACM, 2010

[52] N. S. Good, J. Grossklags, D. K. Mulligan, and J. A. Konstan. Noticing notice: a large-scale experiment on the timing of software license agreements. In Proc. CHI '07. ACM, 2007.

[53] N. S. Good, J. Grossklags, D. K. Mulligan, and J. A. Konstan. Noticing notice: a large-scale experiment on the timing of software license agreements. In Proc. CHI '07. ACM, 2007.

[54] Microsoft. Privacy Guidelines for Developing Software Products and Services. Technical Report version 3.1, 2008.

[55] A. Kobsa and M. Teltzrow. Contextualized communication of privacy practices and personalization benefits: Impacts on users' data sharing and purchase behavior. In Proc. PETS '05. Springer, 2005.

[56] F. Schaub, B. K¨onings, and M. Weber. Context-adaptive privacy: Leveraging context awareness to support privacy decision making. IEEE Pervasive Computing, 14(1):34-43, 2015.

[57] E. Choe, J. Jung, B. Lee, and K. Fisher. Nudging people away from privacy-invasive mobile apps through visual framing. In Proc. INTERACT '13. Springer, 2013.

[58] F. Schaub, B. K¨onings, and M. Weber. Context-adaptive privacy: Leveraging context awareness to support privacy decision making. IEEE Pervasive Computing, 14(1):34-43, 2015.

[59] Article 29 Data Protection Working Party. Opinion 8/2014 on the Recent Developments on the Internet of Things. WP 223, Sept. 2014.

[60] B. Anderson, A. Vance, B. Kirwan, E. D., and S. Howard. Users aren't (necessarily) lazy: Using NeuroIS to explain habituation to security warnings. In Proc. ICIS '14, 2014.

[61] B. Anderson, B. Kirwan, D. Eargle, S. Howard, and A. Vance. How polymorphic warnings reduce habituation in the brain - insights from an fMRI study. In Proc. CHI '15. ACM, 2015.

[62] M. S. Wogalter, V. C. Conzola, and T. L. Smith-Jackson. Research-based guidelines for warning design and evaluation. Applied Ergonomics, 16 USENIX Association 2015 Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security 17 33(3):219-230, 2002.

[63] L. F. Cranor, P. Guduru, and M. Arjula. User interfaces for privacy agents. ACM TOCHI, 13(2):135-178, 2006.

[64] R. S. Portnoff, L. N. Lee, S. Egelman, P. Mishra, D. Leung, and D. Wagner. Somebody's watching me? assessing the effectiveness of webcam indicator lights. In Proc. CHI '15, 2015

[65] M. Langheinrich. Privacy by design - principles of privacy-aware ubiquitous systems. In Proc. UbiComp '01. Springer, 2001

[66] Microsoft. Privacy Guidelines for Developing Software Products and Services. Technical Report version 3.1, 2008.

[67] The Impact of Timing on the Salience of Smartphone App Privacy Notices, Rebecca Balebako , Florian Schaub, Idris Adjerid , Alessandro Acquist ,Lorrie Faith Cranor

[68] R. Böhme and J. Grossklags. The Security Cost of Cheap User Interaction. In Workshop on New Security Paradigms, pages 67-82. ACM, 2011

[69] A. Felt, S. Egelman, M. Finifter, D. Akhawe, and D. Wagner. How to Ask For Permission. HOTSEC 2012, 2012.

[70] A. Felt, S. Egelman, M. Finifter, D. Akhawe, and D. Wagner. How to Ask For Permission. HOTSEC 2012, 2012.

[71] Towards Context Adaptive Privacy Decisions in Ubiquitous Computing Florian Schaub∗ , Bastian Könings∗ , Michael Weber∗ , Frank Kargl† ∗ Institute of Media Informatics, Ulm University, Germany Email: { florian.schaub | bastian.koenings | michael.weber }@uni-ulm.d

[72] M. Korzaan and N. Brooks, "Demystifying Personality and Privacy: An Empirical Investigation into Antecedents of Concerns for Information Privacy," Journal of Behavioral Studies in Business, pp. 1-17, 2009.

[73] B. Könings and F. Schaub, "Territorial Privacy in Ubiquitous Computing," in WONS'11. IEEE, 2011, pp. 104-108.

[74] The Cost of Reading Privacy Policies Aleecia M. McDonald and Lorrie Faith Cranor

[75] 5 Federal Trade Commission, "Protecting Consumers in the Next Tech-ade: A Report by the Staff of the Federal Trade Commission," March 2008, 11, http://www.ftc.gov/os/2008/03/P064101tech.pdf.

[76] The Cost of Reading Privacy Policies Aleecia M. McDonald and Lorrie Faith Cranor

I/S: A Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society 2008 Privacy Year in Review issue http://www.is-journal.org/

[77] IS YOUR INSEAM YOUR BIOMETRIC? Evaluating the Understandability of Mobile Privacy Notice Categories Rebecca Balebako, Richard Shay, and Lorrie Faith Cranor July 17, 2013 https://www.cylab.cmu.edu/files/pdfs/tech_reports/CMUCyLab13011.pdf

[78] https://www.sba.gov/blogs/7-considerations-crafting-online-privacy-policy

[79] https://www.cippguide.org

[80] The Platform for Privacy Preferences Project, more commonly known as P3P was designed by the World Wide Web Consortium aka W3C in response to the increased use of the Internet for sales transactions and subsequent collection of personal information. P3P is a special protocol that allows a website's policies to be machine readable, granting web users' greater control over the use and disclosure of their information while browsing the internet.

[81] Security and Permissions, ANDROID DEVELOPERS, http://developer.android.com/guide/topics/security/security.html (last updated Sept. 13, 2011).

[82] See Foursqaure Privacy Policy

[83] http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1600&context=iplj

[84] Privacy Policy, FOURSQUARE, http://foursquare.com/legal/privacy (last updated Jan. 12, 2011)

[85] Bees and Pollen, "Bees and Pollen Personalization Platform," http://www.beesandpollen.com/TheProduct. aspx; Bees and Pollen, "Sense6-Social Casino Games Personalization Solution," http://www.beesandpollen. com/sense6.aspx; Bees and Pollen, "About Us," http://www.beesandpollen.com/About.aspx.

[86] CFA on the NTIA Short Form Notice Code of Conduct to Promote Transparency in Mobile Applications July 26, 2013 | Press Release

[87] P. M. Schwartz and D. Solove. Notice & Choice. In The Second NPLAN/BMSG Meeting on Digital Media and Marketing to Children, 2009.

[88] F. Cate. The Limits of Notice and Choice. IEEE Security Privacy, 8(2):59-62, Mar. 2010.

[89] https://www.cippguide.org/2011/08/09/components-of-a-privacy-policy/

[90] https://www.ftc.gov/public-statements/2001/07/case-standardization-privacy-policy-formats

[91] Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change. Preliminary FTC Staff Report.December 2010

[92] . See Comment of Common Sense Media, cmt. #00457, at 1.

[93] Pollach, I. What's wrong with online privacy policies? Communications of the ACM 30, 5 (September 2007), 103-108

[94] A Comparative Study of Online Privacy Policies and Formats Aleecia M. McDonald,1 Robert W. Reeder,2 Patrick Gage Kelley, 1 Lorrie Faith Cranor1 1 Carnegie Mellon, Pittsburgh, PA 2 Microsoft, Redmond, WA

http://lorrie.cranor.org/pubs/authors-version-PETS-formats.pdf

[95] Amber Sinha Critique

[96] Kent Walker, The Costs of Privacy, 2001 available at https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-84436409/the-costs-of-privacy

[97] Annie I. Anton et al., Financial Privacy Policies and the Need for Standardization, 2004 available at https://ssl.lu.usi.ch/entityws/Allegati/pdf_pub1430.pdf; Florian Schaub, R. Balebako et al, "A Design Space for effective privacy notices" available at https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/soups2015/soups15-paper-schaub.pdf

[98] Allen Levy and Manoj Hastak, Consumer Comprehension of Financial Privacy Notices, Interagency Notice Project, available at https://www.sec.gov/comments/s7-09-07/s70907-21-levy.pdf

[99] Patrick Gage Kelly et al., Standardizing Privacy Notices: An Online Study of the Nutrition Label Approach available at https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/public_comments/privacy-roundtables-comment-project-no.p095416-544506-00037/544506-00037.pdf

[100] The Center for Information Policy Leadership, Hunton & Williams LLP, "Ten Steps To Develop A Multi-Layered Privacy Notice" available at https://www.informationpolicycentre.com/files/Uploads/Documents/Centre/Ten_Steps_whitepaper.pdf

[101] A Comparative Study of Online Privacy Policies and Formats Aleecia M. McDonald,1 Robert W. Reeder,2 Patrick Gage Kelley, 1 Lorrie Faith Cranor1 1 Carnegie Mellon, Pittsburgh, PA 2 Microsoft, Redmond, WA

[102] Howard Latin, "Good" Warnings, Bad Products, and Cognitive Limitations, 41 UCLA Law Review available at https://litigation-essentials.lexisnexis.com/webcd/app?action=DocumentDisplay&crawlid=1&srctype=smi&srcid=3B15&doctype=cite&docid=41+UCLA+L.+Rev.+1193&key=1c15e064a97759f3f03fb51db62a79a5

[103] Report by Kleimann Communication Group for the FTC. Evolution of a prototype financial privacy notice, 2006. http://www.ftc.gov/privacy/ privacyinitiatives/ftcfinalreport060228.pdf Accessed 2 Mar 2007

http://lorrie.cranor.org/pubs/authors-version-PETS-formats.pdf