ICANN’s Documentary Information Disclosure Policy – I: DIDP Basics

The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (“ICANN”) is a non-profit corporation incorporated in the state of California and vested with the responsibility of managing the DNS root, generic and country-code Top Level Domain name system, allocation of IP addresses and assignment of protocol identifiers. As an internationally organized corporation with its own multi-stakeholder community of Advisory Groups and Supporting Organisations, ICANN is a large and intricately woven governance structure. Necessarily, ICANN undertakes through its Bye-laws that “in performing its functions ICANN shall remain accountable to the Internet community through mechanisms that enhance ICANN’s effectiveness”. While many of its documents, such as its Annual Reports, financial statements and minutes of Board meetings, are public, ICANN has instituted the Documentary Information Disclosure Policy (“DIDP”), which like the RTI in India, is a mechanism through which public is granted access to documents with ICANN which are not otherwise available publicly. It is this policy – the DIDP – that I propose to study.

In a series of blogposts, I propose to introduce the DIDP to unfamiliar ears, and to analyse it against certain freedom of information best practices. Further, I will analyse ICANN’s responsiveness to DIDP requests to test the effectiveness of the policy. However, before I undertake such analysis, it is first good to know what the DIDP is, and how it is crucial to ICANN’s present and future accountability.

What is the DIDP?

One of the core values of the organization as enshrined under Article I Section 4.10 of the Bye-laws note that “in performing its functions ICANN shall remain accountable to the Internet community through mechanisms that enhance ICANN’s effectiveness”. Further, Article III of the ICANN Bye-laws, which sets out the transparency standard required to be maintained by the organization in the preliminary, states - “ICANN and its constituent bodies shall operate to the maximum extent feasible in an open and transparent manner and consistent with procedures designed to ensure fairness”.

Accordingly, ICANN is under an obligation to maintain a publicly accessible website with information relating to its Board meetings, pending policy matters, agendas, budget, annual audit report and other related matters. It is also required to maintain on its website, information about the availability of accountability mechanisms, including reconsideration, independent review, and Ombudsman activities, as well as information about the outcome of specific requests and complaints invoking these mechanisms.

Pursuant to Article III of the ICANN Bye-laws for Transparency, ICANN also adopted the DIDP for disclosure of publicly unavailable documents and publish them over the Internet. This becomes essential in order to safeguard the effectiveness of its international multi-stakeholder operating model and its accountability towards the Internet community. Thereby, upon request made by members of the public, ICANN undertakes to furnish documents that are in possession, custody or control of ICANN and which are not otherwise publicly available, provided it does not fall under any of the defined conditions for non-disclosure. Such information can be requested via an email to [email protected].

Procedure

- Upon the receipt of a DIDP request, it is reviewed by the ICANN staff.

- Relevant documents are identified and interview of the appropriate staff members is conducted.

- The documents so identified are then assessed whether they come under the ambit of the conditions for non-disclosure.

- Yes - A review is conducted as to whether, under the particular circumstances, the public interest in disclosing the documentary information outweighs the harm that may be caused by such disclosure.

- Documents which are considered as responsive and appropriate for public disclosure are posted on the ICANN website.

- In case of request of documents whose publication is appropriate but premature at the time of response then the same is indicated in the response and upon publication thereafter, is notified to the requester.

Time Period and Publication

The response to the DIDP request is prepared by the staff and is made available to the requestor within a period of 30 days of receipt of request via email. The Request and the Response is also posted on the DIDP page http://www.icann.org/en/about/transparency in accordance with the posting guidelines set forth at http://www.icann.org/en/about/transparency/didp.

Conditions for Non-Disclosure

There are certain circumstances under which ICANN may refuse to provide the documents requested by the public. The conditions so identified by ICANN have been categorized under 12 heads and includes internal information, third-party contracts, non-disclosure agreements, drafts of all reports, documents, etc., confidential business information, trade secrets, information protected under attorney-client privilege or any other such privilege, information which relates to the security and stability of the internet, etc.

Moreover, ICANN may refuse to provide information which is not designated under the specified conditions for non-disclosure if in its opinion the harm in disclosing the information outweighs the public interest in disclosing the information. Further, requests for information already available publicly and to create or compile summaries of any documented information may be declined by ICANN.

Grievance Redressal Mechanism

In certain circumstances the requestor might be aggrieved by the response received and so he has a right to appeal any decision of denial of information by ICANN through the Reconsideration Request procedure or the Independent Review procedure established under Section 2 and 3 of Article IV of the ICANN Bye-laws respectively. The application for review is made to the Board which has designated a Board Governance Committee for such reconsideration. The Independent Review is done by an independent third-party of Board actions, which are allegedly inconsistent with the Articles of Incorporation or Bye-laws of ICANN.

Why does the DIDP matter?

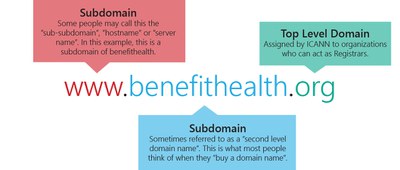

The breadth of ICANN’s work and its intimate relationship to the continued functioning of the Internet must be appreciated before our analysis of the DIDP can be of help. ICANN manages registration and operations of generic and country-code Top Level Domains (TLD) in the world. This is a TLD:

(Source: here)

Operation of many gTLDs, such as .com, .biz or .info, is under contract with ICANN and an entity to which such operation is delegated. For instance, Verisign operates the .com Registry. Any organization that wishes to allow others to register new domain names under a gTLD (sub-domains such as ‘benefithealth’ in the above example) must apply to ICANN to be an ICANN-accredited Registrar. GoDaddy, for instance, is one such ICANN-accredited Registrar. Someone like you or me, who wants to get our own website – say, vinayak.com – buys from GoDaddy, which has a contract with ICANN under which it pays periodic sums for registration and renewal of individual domain names. When I buy from an ICANN-accredited Registrar, the Registrar informs the Registry Operator (say, Verisign), who then adds the new domain name (vinayak.com) to its registry list, and then it can be accessed on the Internet.

ICANN’s reach doesn’t stop here, technically. To add a new gTLD, an entity has to apply to ICANN, after which the gTLD has to be added to the root file of the Internet. The root file, which has the list of all TLDs (or all ‘legitimate’ TLDs, some would say), is amended by Verisign under its tripartite contract with the US Government and ICANN, after which Verisign updates the file in its ‘A’ root server. The other 12 root servers use the same root file as the Verisign root server. Effectively, this means that only ICANN-approved TLDs (and all sub-domains such as ‘benefithealth’ or ‘vinayak’) are available across the Internet, on a global scale. Or at least, ICANN-approved TLDs have the most and widest reach. ICANN similarly manages country-code TLDs, such as .in for India, .pk for Pakistan or .uk for the United Kingdom.

All of this leads us to wonder whether the extent of ICANN’s voluntary and reactive transparency is sufficient for an organization of such scale and impact on the Internet, perhaps as much impact as the governments do. In the next post, I will analyse the DIDP’s conditions for non-disclosure of information with certain freedom of information best practices.

Vinayak Mithal is a final year student at the Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, Punjab. His interests lie in Internet governance and other aspects of tech law, which he hopes to explore during his internship at CIS and beyond. He may be reached at [email protected].