The Rising Stars in Music Loath Losing their Only Platform

Srinagar, J&K: Amid the gaudy Old City area of Srinagar, where the air is heavy with the pungent smell of teargas shells, 25-year-old Ali Saifuddin has been busy working on compositions that he will perform at a prominent indie music festival in Pune in December 2017. Pune may be discovering Saifuddin’s music only now, but he has performed in Dubai and London too, owing to the fanbase he has garnered on social media.

|  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mehmeet Syed’s popularity on social media has taken her to countries like US, UK, Australia and Abu Dhabi (Picture Courtesy: Mehmeet Syed Facebook page) |

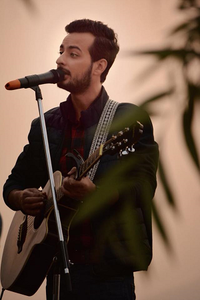

Umar Majeed shot to fame with his rendition of Pakistan’s national anthem on the Santoor | Yawar Abdal, a Kashmiri singer, says he doesn’t see the logic behind keeping the internet shut for months (Picture Courtesy: Yawar Abdal Facebook Page) |

|

It was in 2014 when the budding musician bought recording gear and created a Facebook page. Hours after uploading his first video, Saifuddin became an internet sensation. “I was stunned to see thousands of views on Facebook. People who I had never met with hailed my tunes and encouraged me to produce more,” Saifuddin says.

With 9,000 followers on Instagram and more than 6,000 ‘likes’ on his Facebook page, Saifuddin often gets offers to perform outside Kashmir.

“(As an artist) you need a platform, and in Kashmir, it is the internet that sides with you,” says Yawar Abdal, another popular Youtuber, whose song Tamanna has garnered over 400,000 views since June. “I uploaded a minute-long video on Facebook in April last year. It became viral and made me famous,” Abdal says.

The 23-year-old Pune University student has more than 13,000 followers on Instagram and above 10,000 likes on Facebook. “There are no shows organised in Kashmir. Internet is the only platform where people can broadcast what they posses,” he says.

Frequent curfews, even online, are like a curse for Kashmiris. Internet services are being clamped down in the Valley quite often, particularly after the killing of militant leader Burhan Wani on July 8. Wani’s killing sparked violent protests resulting in the deaths of 15 civilians the very next day. The clashes killed 383 people - including 145 civilians, 138 militants and 100 state and Central security personnel - and around 15,000 others were injured. While many were also put under illegal detention following the outbreak of deadly violence, the government suspended internet for more than six months in 2016.

In such a scenario, where shutdowns are stretching from streets to the social media, it is not surprising to see Kashmiris voice their dissent through art whenever they find a window open. In 2017, internet services were blocked 27 times across various districts of the Valley, either on mobile, or on both mobile and broadband, in the hope that it prevents rumour mongering and instigation of violence.

“This is unnatural and tantamount to choking a person’s right to free speech,” says Saifuddin, who has been criticising the human rights violations in Kashmir with songs that carry a political undertone. Son of medical doctors based in UK, Saifuddin got initiated to rock music through Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin during school days, before heading to Delhi University for a BA degree in 2011. “There I found the treasure of music. I finally had a computer and an internet connection. Youtube became my first, and so far, the only teacher,” recalls Saifuddin. His songs on Youtube include Aye Raah-e-Haq Ke Shaheedon, Phir Se Hum Ubharaygay, and Manzoor Nahi - a song he posted to protest against Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Kashmir in November 2015.

For Mehmeet Syed, whose music was limited to CDs since 2004, internet opened new avenues. Her popularity on social media has taken her to countries like US, UK, Australia and Abu Dhabi among others. “Being on social media is very important as it lets people stay updated about my work. My popularity touched new heights after I took to the internet,” says Syed, who owns a verified Facebook page with more than 1.20 lakh followers. On Instagram, she is a novice. But an internet ban means “heartbreak” to her. “Internet is not shut down in other places witnessing violence and conflict…We are very unfortunate to face internet bans,” says Syed.

“As singers, we have to record songs, mail them for editing, or receive content from studio. Without internet, we are stuck, paralysed,” she says.

Explaining how internet is more than a means of free expression, Mehmeet says, “Times have changed. This is the era of iTunes and YouTube. The songs we release in Kashmir are watched online across the globe. And this is how you earn today.”

The freedom to share content has empowered even the marginalised lot who were only known locally for their talent. Abdul Rashid, a transgender wedding singer popular as ‘Reshma’ in Srinagar’s Old City, became an online sensation after one of her wedding songs was widely viewed on Facebook, and media followed up with stories around her.

“Nobody knew me outside my locality. But today, I get calls from across Kashmir to sing on weddings. This became possible through Facebook. It gave me wide publicity,” Reshma says.

Umar Majeed, a Class 12 student from Zainakoot in Srinagar, is keeping the folk tradition of Kashmir alive with the help of internet. While the 19-year-old inherited skills on Santoor from his father, Abdul Majeed, it was social media that propelled him to fame. Umar played the national anthem of Pakistan on Santoor, accompanied by two other musicians on Rabaab. “The instrumental composition was viewed 450,000 times in two days,” says Umar, adding that they are working on a musical theme of the Indian national anthem as well.

With 5,000 friends on Facebooķ and 2,500 followers on Instagram, Umar has a quite wide network for a schoolkid. “We get a lot of encouragement and confidence when people comment on and appreciate our work online,” he says. But repeated internet ban keeps the young musician away from the much needed feedback.

“When I get an idea, I instantly compose it on Santoor and upload it on Facebook to get viewers’ response… But when there is internet ban, I have no mood to play even when I get an idea, and soon I forget it,” he says.

Mehmeet points out that internet not only promises freedom of expression but also provides monetary support to indie artists through platforms like iTunes, Google Play, Pandora, Amazon and Sawaan. She has been generating revenue to support her music through 21 of her tracks uploaded on these platforms, Mehmeet says.

The repeated shutdown of internet during the Republic Day and Independence Day also sends a wrong message to Kashmiris, says Mehmeet. “We realise that such attitude is step-motherly, which is unacceptable. And we as Kashmiris have not yet reached the stage where we think we have got independence.” Saifuddin seconds her sentiments. “If it is a democracy, then I have a right to speak my heart out. Why would the government choke my voice?” he asks.

When asked if the clamping down of internet service affects his music and earning, Saifuddin retorts poetically: “If not for the internet, I wouldn’t be around. So yes, it pains to see Kashmir being sealed on streets and on the cyberspace as well.

“It makes you angry at times to see things that happen nowhere but in Kashmir.”

Abdal, on the contrary, wants his music to be apolitical. “I sing the songs of Sufi saints and strive to rejuvenate the dying Kashmiri music,” he says.

But, the ban on internet services leaves him perturbed. “Without listeners, you begin losing interest. I hope one day the government understands that there is no logic in keeping the internet shut for weeks and months,” says Abdal, adding that he also observes a drop in demand for live gigs in the absence of internet.

“When you have a lot to share, but the medium through which you could take it to people is blocked, discomfort is what you’re left with.”

Umar Shah and Mir Farhat are Srinagar-based freelance writers and members of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.

Shutdown stories are the output of a collaboration between 101 Reporters and CIS with support from Facebook.