Beyond the PDP Bill: Governance Choices for the DPA

The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, was introduced in the Lok Sabha on 11 December 2019. It lays down an overarching framework for personal data protection in India. Once revised and approved by Parliament, it is likely to establish the first comprehensive data protection framework for India. However, the provisions of the Bill are only one component of the forthcoming data protection framework It further proposes setting up the Data Protection Authority (DPA) to oversee the final enforcement, supervision, and standard-setting. The Bill consciously chooses to vest the responsibility of administering the framework with a regulator instead of a government department. As an independent agency, the DPA is expected to be autonomous from the legislature and the Central Government and capable of making expert-driven regulatory decisions in enforcing the framework.

Furthermore, the DPA is not merely an implementing authority; it is also expected to develop privacy regulations for India by setting standards. As such, it will set the day-to-day obligations of regulated entities under its supervision. Thus, the effectiveness with which it carries out its functions will be the primary determinant of the impact of this Bill (or a revised version thereof) and the data protection framework set out under it.

The final version for the PDP Bill may or may not provide the DPA with clear guidance regarding its functions. In this article, we emphasise the need to look beyond the Bill and instead examine the specific governance choices the DPA must deliberate on vis-à-vis its standard-setting function, which are distinct from those it will encounter as part of its enforcement and supervision functions.

A brief timeline of the genesis of a distinct privacy regulator for India

The vision of an independent regulator for data protection in India emerged over the course of several intervening processes that set out to revise India’s data protection laws. In fact, the need for a dedicated data protection regulation for India, with enforceable obligations and rights, was debated years before the Aadhaar, Cambridge Analytica, and Pegasus revelations captured the public imagination and mainstreamed conversations on privacy.

The Right to Privacy Bill, 2011, which never took off, recognised the right to privacy in line with Article 21 of the Constitution of India, which pertains to the right to life and personal liberty. The Bill laid down express conditions for collecting and processing data and the rights of data subjects. It also proposed setting up a Data Protection Authority (DPA) to supervise and enforce the law and advise the government in policy matters. Upon review by the Cabinet, it was suggested that the Authority be revised to an Advisory Council, given its role under the Bill was limited.

Subsequently, in 2012, the AP Shah Committee Report recommended a principle-based data protection law, focusing on set standards while refraining from providing granular rules, to be enforced through a co-regulatory structure. This structure would consist of central and regional-level privacy commissioners, self-regulatory bodies, and data protection officers appointed by data controllers. There were also a few private members’ bills introduced between 2011 and 2019.

None of these efforts materialised, and the regulatory regime for data protection and privacy remained embedded within the Information Technology Act, 2000, and the Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011 (SPDI Rules). Though the SPDI Rules require body corporates to secure personal data, their enforcement is limited to cases of negligence in abiding by these limited set of obligations pertaining to sensitive personal information only, and which have caused wrongful loss or gain – a high threshold to prove for aggrieved individuals. Otherwise, the Intermediary Guidelines, 2011 require all intermediaries to generally follow these Rules under Rule 3(8). The enforcement of these obligations is entrusted to adjudicating officers (AO) appointed by the central government, who are typically bureaucrats appointed as AOs in an ex-officio capacity.

By 2017, the Aadhaar litigations had provided additional traction to the calls for a dedicated and enforceable data protection framework in India. In its judgement, the Supreme Court recognised the right to privacy as a fundamental right in India and stressed the need for a dedicated data protection law. Around the same time, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) constituted a committee of experts under the chairmanship of Justice BN Srikrishna. The Srikrishna Committee undertook public consultations on a 2017 white paper, which culminated in the nearly comprehensive Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018, and an accompanying report. This 2018 Bill outlined a regulatory framework of personal data processing for India and defined data processing entities as fiduciaries, which owe a duty of care to individuals to whom personal data relates. The Bill provided for the setting up of an independent regulator that would, among other things, specify further standards for data protection and administer and enforce the provisions of the Bill.

MeitY invited public comments on this Bill and tabled a revised version, the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (PDP Bill), in the Lok Sabha in December 2019. Following public pressure calling for detailed discussions on the Bill before its passing, it was referred to a Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) constituted for this purpose. It currently remains under review; the JPC is reportedly expected to table its report in the 2021 Winter Session of Parliament. Though the Bill is likely to undergo another round of revisions following the JPC’s review, this is the closest India has come to realising its aspirations of establishing a dedicated and enforceable data protection framework.

This Bill carries forward the choice of a distinct regulatory body, though questions remain on the degree of its independence, given the direct control granted to the central government in appointing its members and funding the DPA.

Conceptualising an Independent DPA

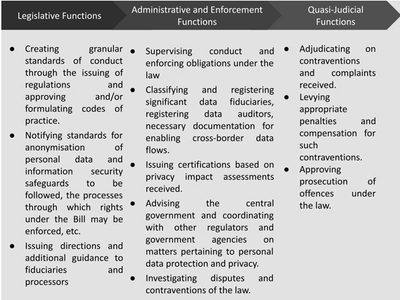

The Srikrishna Committee’s 2017 white paper and its 2018 report on the PDP Bill discuss the need for a regulator in the context of enforcement of its provisions. However, the DPA under the PDP Bill is tasked with extensive powers to frame detailed regulations and codes of conduct to inform the day-to-day obligations of data fiduciaries and processors. To be clear, the standard-setting function for a regulator entails laying down the standards based on which regulated entities (i.e. the data fiduciaries) will be held accountable, and the manner in which they may conduct themselves while undertaking the regulated activity (i.e. personal data processing). This is in addition to its administrative and enforcement, and quasi-judicial functions, as outlined below:

Functions of the DPA under the PDP Bill 2019

At this stage, it is important to note that the choice of regulation via a regulator is distinct from the administration of the Bill by the central or state governments. Creating a distinct regulatory body allows government procedures to be replaced with expert-driven decision-making to ensure sound economic regulation of the sector. At the same time, the independence of the regulatory authority insulates it from political processes. The third advantage of independent regulatory authorities is the scope for ‘operational flexibility’, which is embodied in the relative autonomy of its employees and its decision-making from government scrutiny.

This is also the rationale provided by the Srikrishna Committee in stating their choice to entrust the administration of the data protection law to an independent DPA. The 2017 white paper that preceded the 2018 Srikrishna Committee Report proposed a distinct regulator to provide expert-driven enforcement of laws for the highly specialised data protection sphere. Secondly, the regulator would serve as a single point of contact for entities seeking guidance and will ensure consistency by issuing rules, standards, and guidelines. The Srikrishna Committee Report concretised this idea and proposed a sector-agnostic regulator that is expected to undertake expertise-driven standard-setting, enforcement, and adjudication under the Bill. The PDP Bill carries forward this conception of a DPA, which is distinct from the central government.

Conceptualised as such, the DPA has a completely new set of questions to contend with. Specifically, regulatory bodies require additional safeguards to overcome the legitimacy and accountability questions that arise when law-making is carried out not by elected members of the legislature, but via the unelected executive. The DPA would need to incorporate democratic decision-making processes to overcome the deficit of public participation in an expert-driven body. Thus, the meta-objective of ensuring autonomous, expertise-driven, and legitimate regulation of personal data processing necessitates that the regulator has sufficient independence from political interference, is populated with subject matter experts and competent decision-makers, and further has democratic decision-making procedures.

Further, the standard-setting role of the regulator does not receive sufficient attention in terms of providing distinct procedural or substantive safeguards either in the legislation or public policy guidance.

Reconnaissance under the PDP Bill: How well does it guide the DPA?

At this time, the PDP Bill is the primary guidance document that defines the DPA and its overall structure. India also lacks an overarching statute or binding framework that lays down granular guidance on regulation-making by regulatory agencies.

The PDP Bill, in its current iteration, sets out skeletal provisions to guide the DPA in achieving its objectives. Specifically, the Bill provides guidance limited to the following:

- Parliamentary scrutiny of regulations: The DPA must table all its regulations before the Parliament. This is meant to accord legislative scrutiny to binding legal standards promulgated by unelected officials.

- Consistency with the Act: All regulations should be consistent with the Act and the rules framed under it. This integrates a standard of administrative law to a limited extent within the regulation-making process.

However, India’s past track record indicates that regulations, once tabled before the Parliament, are rarely questioned or scrutinised. Judicial review is typically based on ‘thin’ procedural considerations such as whether the regulation is unconstitutional, arbitrary, ultra vires, or goes beyond the statutory obligations or jurisdiction of the regulator. In any event, judicial review is possible only when an instrument is challenged by a litigant, and, therefore, it may not always be a robust ex-ante check on the exercise of this power. A third challenge arises where instruments other than regulations are issued by the regulator. These could be circulars, directions, guidelines, and even FAQs, which are rarely bound by even the minimal procedural mandate of being tabled before the Parliament. To be sure, older regulators including the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) also face similar issues, which they have attempted to address through various methods including voluntary public consultations, stakeholder meetings, and publication of minutes of meetings. These are useful tools for the DPA to consider as well.

Apart from these, specific guidance is provided with respect to issuing and approving codes of practice and issuing directions as follows:

- Codes of practice: The DPA is required to (i) ensure transparency,[1] (ii) consult with other sectoral regulators and stakeholders, and (iii) follow a procedure to be prescribed by the central government prior to the notification of codes of practice under the Bill.[2]

- Directions: The DPA may issue directions to individual, regulated entities or their classes from time to time, provided these entities have been given the opportunity to be heard by the DPA before such directions are issued.[3]

However, the meaning of transparency and the process for engaging with sectoral regulators remains unspecified under the Bill. Furthermore, the central government has been provided vast discretion to formulate these procedures, as the Bill does not specify the principles or outcomes sought to be achieved via these procedures. The Bill also does not specify instances where such directions may be issued and in which form.

Thus, as per its last publicly available iteration, the Bill remains silent on the following:

- The principles that may guide the DPA in its functioning.

- The procedure to be followed for issuing regulations and other subordinate legislation under the Bill.

- The relevant regulatory instruments, other than regulations and codes of practice – such as circulars, guidelines, FAQs, etc. – that may be issued by the DPA.

- The specifics regarding the members and employees within the DPA who are empowered to make these regulations.

It is unclear whether the JPC will revise the DPA’s structure or recommend statutory guidance for the DPA in executing any of its functions. This is unlikely, given that parent statutes for other regulators typically omit such guidance. As a result, the DPA may be required to make intentional and proactive choices on these matters, much like their regulatory counterparts in India. These are discussed in the section below.

Envisaging a Proactive Role for the DPA

As the primary regulatory body in charge of the enforcement of the forthcoming data protection framework, what should be the role of the DPA in setting standards for data protection?

The complexity of the subject matter, and the DPA’s role as the frontline body to define day-to-day operational standards for data protection for the entire digital economy, necessitates that it develop transparent guiding principles and procedures. Furthermore, given that the DPA’s autonomy and capacity are currently unclear, the DPA will need to make deliberate choices regarding how it conducts itself. In this regard, the skeletal nature of the PDP Bill also allows the DPA to determine its own procedures to carry out its tasks effectively.

This is not uncommon in India: various regulators have devised frameworks to create benchmarks for themselves. The Airports Economic Regulatory Authority (AERA) is obligated to follow a dedicated consultation process as per an explicit transparency mandate under the parent statute. However, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI) has, on its own initiative, formulated regulations to guide its regulation-making functions. In other cases, consultation processes have been integrated into the respective framework through judicial intervention: the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) has been mandated to undertake consultations through judicial interpretation of the requirement for transparency under the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Act, 1997 (TRAI Act).

In this regard, we develop a list of considerations that the DPA should look to address while carrying out its standard-setting functions. We also draw on best practices by Indian regulators and abroad, which can help identify feasible solutions for an effective DPA for India.

The choice of regulatory instruments

The DPA is empowered to issue regulations, codes of practice, and directions under the Bill. At the same time, regulators in India routinely issue other regulatory instruments to assign obligations and clarify them. Some commonly used regulatory instruments are outlined below. The terms used for instruments are not standard across regulators, and the list and description set out below outline the main concepts and not fixed labels for the instruments.

Overview of regulatory instruments

|

|

Circulars and Master Circulars |

Guidelines |

FAQs |

Directions |

|

Content |

Circulars are used to prescribe detailed obligations and prohibitions for regulated entities and can mimic regulations. Master circulars consolidate circulars on a particular topic periodically. |

These may be administrative or substantive, depending on the practice of the regulator in question. |

Issued in public interest by regulators to clarify the regulatory framework administered by them. They cannot prescribe new standards or create obligations. |

Issued to provide focused instructions to individual entities or class of entities in response to an adjudicatory action or in lieu of a current challenge. |

|

Binding character |

They are generally binding in the same manner as regulations and rules. However, if they go beyond the parent Act or existing rules and regulations, they may be struck down following a judicial review. |

They may or may not be binding depending upon the language employed or the regulator’s practice. |

Unclear whether these are binding and to what extent. However, crucial clarifications on important concepts sometimes emerge from FAQs. |

Binding in respect of the class of regulated entities to whom this is issued. |

|

Parliamentary scrutiny |

Unlike regulations, these do not have to be laid before the Parliament. |

|||

Thus, all these instruments, to varying degrees, have been used to create binding obligations for regulated entities. The choice of regulatory instrument is not made systematically. Indeed, even a hierarchy of instruments and their functions are not clearly set out by most regulators. The rationale for deciding why a circular is issued as against a regulation is also unclear. A study on regulatory performance in India by Burman and Zaveri (2018) has highlighted an over-reliance on instruments such as circulars. As per their study, between 2014 and 2016, RBI and SEBI issued 1,016 and 122 circulars, as against 48 and 51 regulations, respectively. These circulars are not bound by the same pre-consultative mandate nor are they mandated to be laid before the Parliament. While circulars may have been intended for routine to routinely used to lay down administrative or procedural requirements, the study narrows its frame of reference to circulars which lay down substantive regulatory requirements. In this instance, it is unclear why parliamentary scrutiny is mandated for regulations alone, and not for instruments like circulars and directions, even though they lay down similarly substantive requirements. Furthermore, there have also been instances where certain instruments like FAQs have gone beyond their advisory scope to provide new directions or definitions that were not previously shared under binding instruments like regulations or circulars.

The DPA has been provided specific powers to issue regulations, codes of practice, and directions. However, the rationale for issuing one instead of the other has been absent from the PDP Bill so far. In such a scenario, it is important that the DPA transparently outlines the types of instruments it wishes to use, whether they are binding or advisory, and the procedure to be followed for issuing each.

Pre-legislative consultative rule-making

Participatory and consultative processes have emerged as core components of democratic rule-making by regulators. Transparent consultative mechanisms could also ameliorate capacity challenges in a new regulator (particularly for technical matters) and help enhance public confidence in the regulator.

In India, several regulators have adopted consultation mechanisms even when there is no specific statutory requirement. SEBI and IBBI routinely issue discussion papers and consultation papers. The RBI also issues draft instruments soliciting comments. As discussed previously, TRAI and AERA have distinct transparency mandates under which they carry out consultations before issuing regulations. However, these processes are not mandated all forms of subordinate legislation. Taking cognizance of this, the Financial Sector Legislative Reform Committee (FSLRC) has recommended transparency in the regulation-making process. This was carried forward by the Financial Stability and Development Council (FSDC), which recommended that consultation processes should be a prerequisite for all subordinate legislations, including circulars, guidelines, etc. A study on regulators’ adherence to these mandates, spanning TRAI, AERA, SEBI, and RBI, demonstrated that this pre-consultation mandate is followed inconsistently, if at all. Predictable consultation practices are therefore critical.

Furthermore, the study stated that it could not determine whether the consultation processes yielded meaningful participation, given that regulators are not obligated to disclose how public feedback was integrated into the rule-making process. Subordinate legislations issued in the form of circulars and guidelines also do not typically undergo the same rigorous consultation processes. Thus, an ideal consultation framework would comprise:

- Publication of the draft subordinate legislation along with a detailed explanation of the policy objectives. Further, the regulator should publish the internal or external studies conducted to arrive at the proposed legislation to engender meaningful discussion.

- Permitting sufficient time for the public and interested stakeholders to respond to the draft.

- Publishing all feedback received for the public to assess, and allowing them to respond to the feedback.

However, beyond specifying the manner of conducting consultations, it will be important for the DPA to determine where they are mandatory and binding, and for which type of subordinate legislations. These are discussed in the next section.

Choice of consultation mandates for distinct regulatory instruments

While the Bill provides for consultation processes for issuing and approving codes of practice, no such mechanism has been set out for other instruments. Nevertheless, specifying consultation mandates for different regulatory instruments is important to ensure that decision-making is consistent and regulation-making remains bound by transparent and accountable processes. As discussed above, regulatory instruments such as circulars and FAQs are not necessarily bound by the same consultation mandates in India. This distinction has been clarified in more sophisticated administrative law frameworks abroad. For instance, under the Administrative Procedures Act in the United States (US), all substantive rules made by regulatory agencies are bound by a consultation process, which requires notice of the proposed rule-making and public feedback. This does not preclude the regulatory agency from issuing clarifications, guidelines, and supplemental information on the rules issued. These documents do not require the consultation process otherwise required for formal rules. However, they cannot be used to expand the scope of the rules, set new legal standards, or have the effect of amending the rules. Nevertheless, agencies are not precluded from choosing to seek public feedback on such documents.

Similarly, the Information Commissioner’s Office in the United Kingdom (UK) takes into consideration public consultations and surveys while issuing toolkits and guidance for regulated entities on how to comply with the data protection framework in the UK.

Here, the DPA may choose to subject strictly binding instruments like regulations and codes of practice to pre-legislative consultation mandates, while softer mechanisms like FAQs may be subject to the publication of a detailed outline of the policy objective or online surveys to invite non-binding, advisory feedback. For each of these, the DPA will nonetheless need to create specific criteria by which it classifies instruments as binding and advisory, and further outline specific pre-legislative mandates for each category.

Framework for issuing regulatory instruments and instructions

While the DPA is likely to issue several instruments, the system based on which these instruments will be issued is not yet clear. Without a clearly thought-out framework, different departments within the regulator typically issue a series of directions, circulars, regulations, and other instruments. This raises questions regarding the consistency between instruments. This also requires stakeholders to go through multiple instruments to find the position of law on a given issue. Older Indian regulators are now facing challenges in adapting their ad hoc system into a framework. For example, the RBI currently issues a series of circulars and guidelines that are periodically consolidated on a subject-matter basis as Master Circulars and Master Directions. These are then updated and published on their website. IBBI also publishes handbooks and information brochures that consolidate instruments in an accessible manner.

While these are useful improvements, these practices cannot keep pace with rapid changes in regulatory instructions and are not complete or user-friendly (for example, the subject-matter based consolidation does not allow for filtering regulatory instructions by entity). Other jurisdictions have developed different techniques such as formal codification processes to consolidate regulations issued by government agencies under one unified code, register, or handbook, websites that allow for searches based on different parameters (subject-matter, type of instrument, chronology, entity-based), and guides tailored to different types of entities. The DPA, as a new regulator, can learn from this experience and adopt a consistent framework right from the beginning.

Further, an ethos of responsive regulation also requires the DPA to evaluate and revise directions and regulations periodically, in response to market and technology trends. A commitment to periodic evaluation of subordinate legislations entrenched in the rules is critical to reducing the dependence on officials and leadership, which may change. For instance, the IBBI has set out a mandatory review of regulations issued by it every three years.

Dedicating capacity for drafting subordinate legislations

The DPA has been granted the discretion to appoint experts and staff its offices with the personnel it needs. A study of European data protection authorities shows that by the time the General Data Protection Regulation, 2016 became effective, most of the authorities increased the number of employees with some even reporting a 240% increase. The annual spending on the authorities also went up for most countries. While these authorities do not necessarily frame subordinate legislations, they nonetheless create guidance toolkits and codes of practice as part of their supervisory functions.

In this regard, the DPA will need to ensure it has dedicated capacity in-house to draft subordinate legislations. Since regulators are generally seen as enforcement authorities, there is inadequate investment in capacity-building for drafting legislations in India.

Moreover, considering the multiplicity of instruments and guidance documents the DPA is expected to issue, it may seek to create templates for these instruments, along with compulsory constituents of different types of instruments. For instance, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner is required to include a mandatory set of components while issuing or approving binding industry codes of practice.

Conclusion

The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 (in the final form recommended by the JPC and accepted by the MeitY) will usher in a new chapter in India’s data protection timeline. While the Bill will finally effectuate a nearly comprehensive data protection framework for India, it will also establish a new regulatory framework that sets up a new regulator, the DPA, to oversee the new data protection law. This DPA will be empowered to regulate entities across sectors and is likely to determine the success of the data protection law in India.

Furthermore, the DPA must not only contend with the complexity of markets and the fast pace of technological change, but it must also address anticipated regulatory capacity deficits, low levels of user literacy, the number and diversity of enities within its regulatory ambit, and the need to secure individual privacy within and outside the digital realm.

Thus, looking ahead, we must account for the questions of governance that the forthcoming DPA is likely to face, as these will directly impact how entities and citizens engage with the DPA. In India, regulatory agencies adopt distinct choices to fulfil their functions. Regulators have also fared variably in ensuring transparent and accountable decision-making driven by demonstrable expertise. Even if the final form of the PDP Bill does not address these gaps, the DPA has the opportunity to integrate benchmarks and best practices as discussed above within its own governance framework from the get-go as it takes on its daunting responsibilities under the PDP Bill.

(The authors are Research Fellow, Law, Technology and Society Initiative and Project Lead, Regulatory Governance Project respectively at the National Law School of India University, Bangalore. Views are personal.)

This post was reviewed by Vipul Kharbanda and Shweta Mohandas

References

- For a discussion on distinct regulatory choices, please see TV Somanathan, The Administrative and Regulatory State in Sujit Choudhary, Madhav Khosla, et al. (eds), Oxford Handbook of the Indian Constitution (2016).

- On best practices for consultative law-making, see generally European Union Better Regulation Communication, Guidelines for Effective Regulatory Consultations (Canada), and OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy: The Governance of Regulators, 2014.

[1] Personal Data Protection Bill 2019, § 50(3).

[2] Personal Data Protection Bill 2019, § 50(4).

[3] Personal Data Protection Bill 2019, § 51.