A Public Discussion on Criminal Defamation in India

Event details

When

from 05:30 PM to 07:30 PM

Where

|

|---|

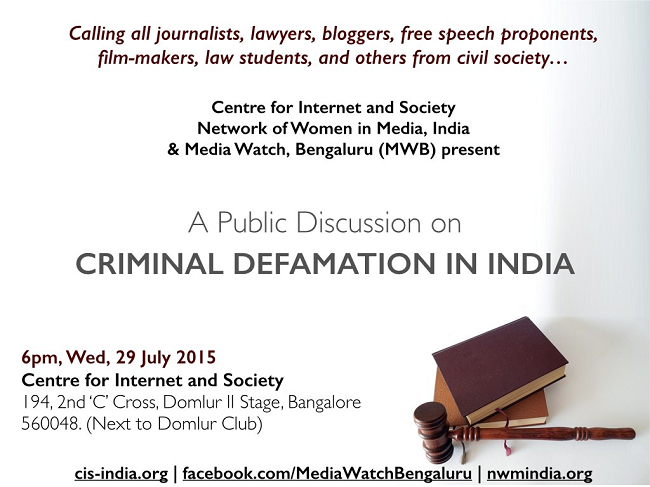

| Pictured above: A poster of the event. |

Decriminalising Defamation in India: A Brief Statement of Issues

Subramanian Swamy’s petition to decriminalise defamation has been joined in the Supreme Court by concurring petitions from Rahul Gandhi and Arvind Kejriwal. Defamation is criminalised by sections 499 and 500 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC). Swamy and his unlikely cohorts want the Supreme Court to declare that these criminal defamation provisions interfere with the right to free speech and strike them down.

Although news coverage of the case has focused on the motivations and arguments of the three politicians, defamation should not be the sole province of celebrities and the powerful. Unfortunately, criminal defamation has emerged as a new system of censorship to silence journalists, writers, and activists. SLAPP suits (Strategic Lawsuits against Public Participation) are being increasingly used by large corporations to frighten and overwhelm critics and opponents. SLAPP suits are not designed to succeed – although they often do, they are intended to intimidate, harass, and outspend journalists and activists into submission.

The law of defamation rests on uncertain foundations. In medieval Europe defamation was dually prosecuted by the Church as a sin equal to sexual immorality, and by secular courts for the threat of violence that accompanied defamatory speech. These distinct concerns yielded a peculiar defence which fused two elements: truth, which shielded the speaker from the sin of lying; and, the public good, which protected the speaker from the charge of disrupting the public peace. This dual formulation – truth and the public good – remains the primary defence to defamation today.

India does not have a strong ‘fair comment’ defence to protect speech that is neither true nor intrinsically socially useful. This bolsters the law’s reflexive censorship of speech that falls outside the bounds of social utility and morality such as parody, caricature, outrageous opinion, sensationalism, and rumour. This failure affects cartoonists and tabloid sensationalism alike.

Defamation law is also open to procedural misuse to maximise its harrassive effect. Since speech that is published on the Internet or mass-printed and distributed can be read almost anywhere, the venue of criminal defamation proceedings can be chosen to inconvenience and exhaust a speaker into surrender. This motivation explains the peculiarly remote location of several defamation proceedings in India against journalists and magazine editors.

The offence of defamation commoditises reputation. While defamation remains a crime, the state must prosecute it as it does other crimes such as murder and rape. This merits the question: should the state expend public resources to defend the individual reputations of its citizens? Such a system notionally guarantees parity because if the state were to retreat from this role leaving private persons to fight for their own reputations, the market would favour the reputations of the rich and powerful at the expense of others.

These and other issues demand an informed and rigorous public discussion about the continued criminalisation of defamation in India.