Modi's Valley hug sparks swadeshi talk

But that embrace, and what it conveyed, is now becoming the subject for an intense debate among techies here. Is Modi giving in too much to the Googles and Facebooks of the world, when there is so much technology talent within India? Is he taking the easy way out by handing out critical pieces of his Digital India vision to global incumbents rather than build domestic capabilities?

"When the government wanted to build a citizen engagement platform earlier this year, they depended on Google. Now when they want Wi-Fi in railway stations, it's again Google. These are things that can be done by our companies, otherwise we will not be able to create our own digital industry. Remember, we are the people who built Aadhaar," said an industry veteran who did not want to be named.

Nitin Pai, co-founder of Takshashila, an independent policy research and advocacy body that provides services for government agencies, NGOs and corporations, said Modi's team should make a careful distinction between national interest and MNCs' commercial interest. "Many MNCs have come forward to participate in Digital India initiatives. The government will have to look at offering sufficient incentives for innovation to domestic tech companies, many of whom are coming with innovative business models," he said.

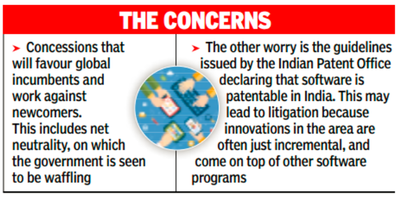

Speaking to a cross-section of tech companies here, two sets of concerns emerge. One relates to the concessions that will work in favour of global incumbents and against newcomers - the latter is likely to add more value in the long term. This includes the issue of net neutrality , on which the government is seen to be waffling, and the guidelines issued by the Indian Patent Office declaring that software is patentable in India.

The new guidelines will make it easier for companies to file for software patents in India. But software patenting has become hugely controversial globally , because innova tions in the area are often just incremental, and come on top of other software programs.Besides, patenting is expensive and is often the subject of litigation, both of which work against small ventures with little resources. Companies like Google have spent billions of dollars to buy patents.

Venkatesh Hariharan, member of software product think-tank iSpirt, said the new guidelines would make it easier for bigger companies to file software patents, but for smaller firms and startups, the move could be detrimental."They could end up fighting patent litigations. In the US, 37% of patent litigation is around software and business patents," he said.

Sunil Abraham, executive director in research organization Centre for Internet and Society , fears litigation could kill local innovation. He cited a recent example where a Delhi high court order asked Indian handset manufacturer Micromax to pay 1.25%-2% of the selling price of its devices to Ericsson that had claimed infringement of patents.

The other set of issues relates to certain rules and regulations in India that place significant obstacles before small technology ventures. This is resulting in many ventures shifting their registered offices to Singapore or the US.

Albinder Dindsa's on-demand delivery service Gro fers is among the latest to create a holding company in Singapore. "It is challenging to do business in India. Even opening a bank account took time. We thought it would be easier to do an IPO if we are in Singapore," he said.

A senior industry analyst who did not want to be named said that till last year, two out of four ventures were moving out of India, but now that figure is three out of four. "I would expect the government to do something about it. In fact, the finance minister did say in June that the issues would be addressed within 30 days. But nothing has happened."

Also, it is expensive for angel investors overseas to invest in Indian startups.

India disallows startups from offering stock options to foreign nationals, which makes it difficult for them to access seasoned mentors.