Concerns over central snoop

The article by Aloke Tikku was published in the Hindustan Times on June 28, 2013. Sunil Abraham is quoted.

The Rs. 400-crore project — tentatively called the Central Monitoring System (CMS) — will not only allow the government to listen to a target’s phone conversation but also track down a caller’s precise location, match his voice against known suspects’ before the call is completed and see what people have been up to on the internet.

And then, it can also use analytics to discover possible links — between suspected terrorists, criminals or just about anybody — from the internet and phone data. All this will be done from one place without keeping the internet or phone service provider in the loop — something the telecom and home ministries insist will enhance citizens’ privacy.

Both ministries also insist that the CMS won’t change the rules of the game. “The process to seek authorisation for interception will not be diluted,” a home ministry official promised.

So is everything hunky dory?

Hardly. But technology — in this case, the CMS — is a smaller part of the problem.

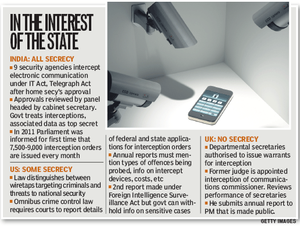

The bigger chunk is the process of approving “lawful interception” orders and the lack of transparency around it.

|

It was in December 1996 that the Supreme Court held that the State could spy on its citizens in extraordinary circumstances but, as an interim measure, made it mandatory for the home secretary to approve each and every such request. Telecom minister Kapil Sibal, who appeared in this case in the mid-1990s, convinced the court that it didn’t have the powers to order that a judge decide each phone-tapping case. Instead, Sibal suggested that this power remain with the executive on lines of the law in the UK. A former home secretary, however, conceded that they hardly have the time to apply their mind before signing a wiretap order. |

|

|---|

That isn’t surprising. The home secretary approves around 7,500-9,000 interception orders every month. That means he or she has to sign an average of 300 orders every day without a break.

If he were to spend just 30 seconds on each case, he would have to keep aside four-and-a-half hours just approving interception orders every day.

An official said the ministry was considering a suggestion to pick up a fixed number of cases at random for closer scrutiny before approval.

Many believe this might not be enough. It is argued that the government — which was trying to replicate surveillance technology from the west — needs to adopt their safeguards and transparency norms too.

Sunil Abraham, executive director of the Bangalore-based Centre for Internet and Society, said he didn’t have a problem with CMS as long as it didn’t go for blanket surveillance.

“But there is no reason why the executive — and not a judge — should have the powers to decide on phone-tapping requests,” he said. Or for that matter, why shouldn’t there be an independent audit of phone-tapping decisions, their implementation and outcome?

“The aggregated data should be put in the public domain,” Abraham said. The US has such provisions. So does Britain, which inspired Sibal to argue for retaining interception powers with the executive in the mid-1990s. It is time to follow-up on that model.