Access to Knowledge

Introduction

In the middle of the 16th century, Queen Mary was faced with a difficult question that was brought to her by none other than most powerful publishing house in England at the time. The Stationers, like any other craft guild in the business of printing and producing books loved a monopoly in the profits of their books and terribly feared competition.[1] Therefore, they went to Queen Mary with the request of a royal charter. This charter would allow them to seize illicit editions of their books and bar the publication of books unlicensed by the crown. The Queen suddenly thought that this could indeed be a more efficient way to squash sedition and dissent through censorship by puppeteering this craft guild than previous, perhaps less subtle means like torture and death. In 1557, she granted them this early form of a copyright. Notice how the author or the creator of the work has no place in this agreement and the origins of intellectual property in English law are based on privilege, namely power and profit. This rhetoric, however, changes with the coming of the 18th century and the passing of the Act of Anne in 1707 to one of creativity and learning. The concern for the author has a steady positivist rise after this in the tug of war over intellectual property. In the case Miller v Taylor in 1769, the author sought to extend copyright to common law. Three judges ruled in favor of this motion and two judges ruled against.[2]

A closer examination at the reasoning provided by the three assenting judges will tell us almost all the philosophical justifications of intellectual property. The first judge called upon his notion of justice and said it is just that the author control the destiny of his work as it is a product of his labor. The second judge said that extending the copyright would encourage creativity by making the work the creator’s property. The third judge said it is the authors natural right as the work wouldn’t exist if not for the mental labor of the author. Together, justice, incentives and natural rights are the cornerstones of the justifications of intellectual property.

Although history is littered with theories on property, there have been only sparse discussions on intellectual property. The question then arises, can intellectual property be accommodated within normal property. The similarity is in the fact that intellectual property is also a relationship between people but the difference lies in the fact that the object is an abstract one.[3]

This leads many to believe that it cannot be subject to the same rules of property. The first dissenting judge in Miller v Taylor, for example, said that abstract ideas cannot be occupied like corporeal objects so they cannot be property. He said the author deserves a reward which the Act of Anne provides in the form of limited monopoly but that’s about it. In fact, an idea is almost the perfect example of a resource like the air or light that is not zero sum and inexhaustible in that my use of it doesn’t take away from your use of it. Neither air nor light can become personal property which leaves ideas in a property limbo. This leaves room for very interesting discussions and debates over the existence of intellectual property and the place it should occupy in society. This discourse has largely taken two forms: the deontological and the consequentialist. Deontological justifications for IP come from a priori reasons like rights or duties which can be established in many forms. There is the ontological basis for rights which answers questions like whether rights exist and if so, where they come from. One of the preeminent figures in this discourse has been John Locke, an English philosopher whose argument for individual property as “natural rights” remains relevant even today when applied to intellectual property. Locke’s major assumptions in his claim were:

- God has given the world to people in common.

- Every person owns his own personality.

- A person’s labor belongs to him.

- When a person mixes his labor with something in the commons he makes it his property.

- The right of property is contingent upon its being good for commoners.[4]

In order to extend this argument, Locke says that exclusive ownership of a resource is a precondition for production. Ideas before labored upon by people, however, are not exclusively owned which resists the cross application of his ideas to intellectual property. Another impediment in extending the natural right to intellectual property is the 5th assumption. Intellectual labor, in annexing an idea, stops it from becoming a part of the intellectual commons. If this labor, armed with the property of becoming property is doing a disservice to society, then it may not be a natural right at all. The notion that ideas are a part of the intellectual commons is also one that needed evidence and Locke found that in scripture as Judeo-Christian philosophy clearly advocates the idea of all worldly resources being part of the commons.

Hegel, on the other hand, took the route of personality theory. He argued that if individuals have claims to anything, they had to be considered an individual first. He states that in order to be individuals, people must have a moral claim to things like their character traits, feelings, talents and experience.[5] The definition of these aspects or the process of self-actualization requires an interaction with tangible and intangible objects in the world. The external actualization process requires property that includes intellectual property for Hegel as he sees the works as an extension or an establishment of the self in the external world that embody the person’s personality in an inseparable and even immortal way.

Another form is in linguistics, where we ask questions like what we mean when we say rights and property. Skinner said that in the history of intellectual property law, the social context of its use and the matrix of assumptions involved in reference is the determining factor. This is why the history of intellectual property is as important as and to the philosophical underpinnings.

The consequentialist justifications of IP assume that the specious connection between IP and creativity is fact and warn of a chilling effect on creative activity in the absence of IP. History shows us that the relationship between IP and creativity is local and contingent rather than necessary and universal. Imperial China, for example, was a creative and inventive empire that gave rise to many technologies and artistic subcultures without any promise of IP. Indeed, Marx’s historical materialism could be seen as condemning IP as a superstructural phenomenon in the industrial development phase of capitalist societies and one that a future society can function well without.[6] If one was interested in the consequentialist debate over IP, then historical empirical data would be more important than an a priori analysis.

The lack of a definitive philosophical, ethical or normative justification for the existence of Intellectual Property rights unlike those for free expression or equal treatment under the law shows us that its application needs to be tempered with other considerations. If, as Rawls suggested, we hide behind the veil of ignorance and tried to form an ideal society, then IP may not feature within it as it tends to create social stratification and further marginalizes the least advantaged in social life and democratic culture.[7] Since IP’s are liberty intrusive privileges that do not “allow the most extensive liberty compatible with a like liberty for all.” or “benefit the least advantaged.” or are “open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity.”, their utilitarian claims of creativity have to answer to the injustices that manifest from them before they get a carte blanche in society.

The access to knowledge has been a yearning of society to shift and dilute the concentration of this most precious of resources because of the old adage “knowledge is power”. This concept, however, can be understood from many lenses including the sociological and the legal. At first, in order to understand the importance of the legal entities under access to knowledge, we must explore its saliency in society.

Humanity world over is at the cusp of a major shift in the production, consumption, dissemination and distribution of knowledge. This warrants changes in frameworks of looking at knowledge, information and data in the digital era at multiple levels and by multiple players including students, academics, entrepreneurs, researchers, civil society and the State. In order to understand why and how knowledge matters in the world today, we must see how it makes a difference in our world and how it materially changes the world.

Many prominent economists and social theorists have sought to claim that knowledge has affected the organization of society in a manner that is different than in previous eras though knowledge has been an organizing principle of society throughout history. How the exact time of the shift and the nature of the shift are catalogued will depend on what category the basis is. From an economic perspective, Marx said that the capitalist system depends on the constant improvement and dynamism of technology. The real understanding of the role of knowledge in our economy came when Robert Solow posited that the majority of economic growth in the beginning of the 20th century was less due to labor or capital and more due to technological changes. These advances in knowledge came in the form of new machines to new production techniques that made the production process more efficient.[8]

Fritz Machlup stated that in the 1960’s the change in the knowledge intensity of the economy was marked by “an increase in the share of ‘knowledge-producing’ labor in total employment.” The Harvard historian Daniel Bell observed in his study of post-industrial societies that 1/3rd of the US workers were employed in the service industry at the turn of the century but by the 1980’s almost 7/10ths of the workers were employed in the service industries.[9]

People who were employed in the industrial sectors were flocking steadily to finance, education, information technology and the cultural industry. The movements of people came as a reaction to the movement of profitability from industrial sectors to finance, biotechnology and information technology. Knowledge basically is a positive feedback loop which means that as more information and communication technologies emerge, it allows more innovation. Manuel Castell categorizes this shift in the place of knowledge as a global one even though it’s concentrated in a few wealthy countries because all the economies ultimately depend on the global one. The disparity between countries is still massive but it used to be just in terms of raw materials and manufactured goods but now at a global level, there is a huge knowledge (high technology low technology, high knowledge services low knowledge services) disparity between wealthy and non-wealthy countries. This claim may seem to imply that knowledge is simply technical and scientific, but there are obviously other important kinds of knowledge like ethical and humanities knowledge. The point here is that the enhanced ability of humans to organize and employ specific kinds of technical and scientific knowledge has created a huge shift in the global economy similar to the effect of the increase in access to knowledge from the invention of printing press. This shift in the importance of knowledge has made our health better as well. The average lifespan has increased exponentially in the past half century and it is our scientific advancement in the mechanisms of disease and medicine that has aided this achievement.

When there is so much integral societal dependence on knowledge, the non market production of knowledge is essential for equality in access to this knowledge. Yochai Benkler stated that the processing power of the modern computers linked together on the internet creates a platform that allows for new kinds of collaboration. Apart from new kinds of political activism, it also leads to decentralized knowledge production like open source/ free software and Wikipedia.

Within this context of the digital turn, openness and transparency are gaining newer significance. On the one hand emerging participatory models of openness like Wikipedia[10] are increasingly pushing us to look beyond the traditional models of the bygone century;[11] on the other hand these models are being thought of to be effective even in governance and policy making. Open data,[12] for instance is becoming a key prerequisite for the State and civil society alike in imagining better governance models. This could potentially create a pre-condition for the transformation of society into a ‘Knowledge Society’, wherein the citizen is increasingly repositioned from a ‘spectator’ to ‘spect-actor’.[13] Eventually, the distinction between a knowledge society and governance could get blurred. However, this process needs strong civil society players to catalyze and cultivate an effective knowledge society. Such work happens at multiple layers of policy coupled with advocacy, research, dissemination and infrastructure creation. The larger policy debate happens in the form of a contest between understandings of knowledge. The two sides are knowledge as property versus knowledge as a common resource. This tension is explored in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The Right to Access to Knowledge

The discourse around the access to knowledge has been around for a while as it is inscribed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which was adopted in 1948. Article 27 of the charter attempts to bring about a balance between the right of access and the protection of material interests.

Article 27[14]

Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits. Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.

Here, many academics and Access to Knowledge theorists posit that the right to access to knowledge is the more important right. This is because the right to material protection or rather the Intellectual Property (IP) right is ultimately for sale and transferrable so is not inalienable like the right to access to knowledge. Many right to knowledge theorists are of the opinion that the level of IP protection currently in place in the world is too much.

In 1996, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)[15] was adopted by the General Assembly of the UN. As we may expect, the right to free speech has a longer history of acceptance and positivist outlook on it. Article 19 of the ICCPR reads as follows:

“Article 19.

- Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

- Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

- The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary:

- For respect of the rights or reputations of others;

- For the protection of national security or of public order (order public), or of public health or morals.” (Italics are mine)

The idea that free speech includes the right to seek and receive is something that will be discussed in the chapter on free speech but the important positive externality or reading that one can glean from this wording is that the access to knowledge becomes a right.

|

|---|

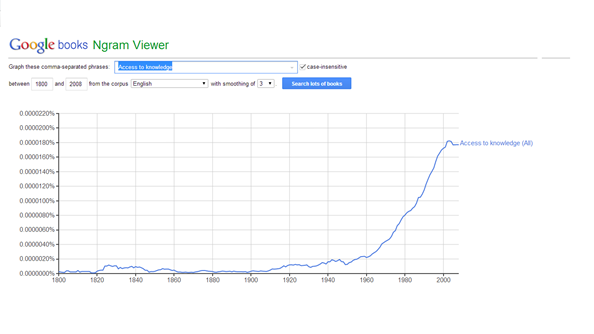

| Above: Google books Ngram Viewer |

However, as you can see in the graph, the discourse around Access to knowledge doesn’t begin to really take off until the early 1960’s when the U.S government was just starting to build a network between computers. In the early stages of the modern internet around the early 1980’s the discourse around access to knowledge becomes even more frequent. This is because intellectual property rights started to eclipse the astronomical increase in the production of knowledge and vast portions of the world’s population remained in the dark. Especially, the production of academic knowledge has increased exponentially in the recent past which has made it essential that the barriers to this knowledge are attenuated as much as possible.Now that we have explored the sociological aspect of access to knowledge and the philosophical debates around it, let us look at how it is codified in law. Specifically we will look at copyright and patents.

Patents

What are Patents?

Of all forms of intellectual property rights (IPR) patents are said to be the most restrictive, granted to inventors of devices or processes on the basis that the invention is novel, can be applied for a useful function, andinvolves an inventive step (and may not be obvious to a professional in the relevant field).

Under Indian patent law, a patent is a statutory right for an invention, giving the inventor the exclusivity to prevent others from making, using, or selling the invention—unless, of course, they are to receive permission from the right holder and pay the necessary royalty fees to do so. For this reason, a patent holder is said to have a monopoly over the invention. [16] In return for this exclusivity, the right holder must disclose a detailed, accurate and complete written description of the invention to be available for the public.[17]

A patent may be a utility patent, issued for the invention of a new and useful process, machine or product; a design patent, for a new and original design to be used in the manufacturing of a product; or a plant patent, for a new and distinct, invented or discovered type of plant.[18] Subject matter that is unpatentable in India includes an invention that is immoral, an invention which claims anything contrary to natural laws (e.g. gravity), the discovery of anything occurring in nature, and the formulation of an abstract theory.[19] That being said, a patentable invention generally must be able to result in a useful, concrete and tangible result, although restrictions of what is not patentable may vary country to country.

Patents are valid for a limited period of time; generally 20 years from the start of the term. A patent’s exclusivity is also limited to the country in which it was granted, meaning that a patent holder may not be able to exclude others from the making, using, or selling of a similar invention in a different jurisdiction that would otherwise infringe upon the their IP right.[20]

Effects on Innovation

There are vast perspectives around the adoption and application of patents, ranging from a strong opposition—by those in favour of free and widespread access to products of innovation and knowledge processes (e.g. medicines and educational materials)—to those in strong support of a more restrictive intellectual property (IP) regime, as a means of protecting the inventor and his or her inventions.

One of the underlying principles for the consideration and enforcement of a patent regime is the claim that this form of IPR serves as an incentive for innovation to take place. By offering a “reward” in the form of statutory recognition, protection, and remuneration, the granting of a patent may encourage innovation. An opposing viewpoint to such a claim, however, may argue that patents do not encourage innovation, but stifle it, by preventing others from being able to innovate through their enforcement. Just as well, a patent is granted after the fact, and the odds of one’s application being approved are quite slim—not to mention expensive!—so a patent would not be an ideal form of incentive, with remuneration only taking place when one’s patent is infringed or one’s monopoly abused.

One’s monopoly may be abused when the right holder of a patent (or thousands!) brings an industry to a standstill by shutting out others from having their new inventions reach the market. Often, patents may prevent the manufacturing and selling of innovations that are not actually relevant, but claim by the right holder to fall within the scope of the patented invention.

The effects of the excessive granting and enforcement of patents may trickle down to the level of the individual when the economic threshold for starting a new business increases, one’s business’s profitability reduces due to the payments of royalties and legal expenses, and the potential for such an entrepreneur to scale beyond national boundaries is undermined.[21]

| Case Study: Pervasive Technologies |

|---|

|

Because of these limitations placed onto others by patent holders, small-to-medium business and enterprises in India and China tend to ignore existing IPR for inventions they may use within their manufactured products due to the high costs associated to seeking permission and paying royalties to the right holder. For this reason, these businesses may only begin to develop protection and risk-mitigation strategies when they have scaled up and can afford to do so.[22] A phenomenon that has risen out of a restrictive market and resulting repeated efforts to get around such restrictions is the “gray” market, where mobile phone are being manufactured with the likelihood of infringing upon a number of existing patents for inventions used in the manufactures. Mobile phones that are entirely legal may cost well over INR 8000/- (US $120) when gray market devices generally range from INR 3000/- to INR 4000/- (US $48-60), demonstrating the high price of patents on the availability of hardware.[23] The term, pervasive devices, coined by the Centre for Internet & Society, largely refers to sub-$100 communication devices that are becoming near-ubiquitous as a result of their increased availability to reach larger demographics of lesser income brackets. Software Technologies Most commonly, software producers from India do not own the rights to the IP they have created and instead adopt a “software as a service” (SAAS) business model, within which contracts signed require all IP developed to be signed over to the client. As international players continue to register a multitude of software patents, it becomes increasingly difficult for Indian companies to move away from this SAAS model to developing their own proprietary products due to the increased risk of litigation.[24] |

Pre-Grant and Post Grant

Upon signing the Trade Related Aspects Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement, India introduced two kinds of patent oppositions, where an individual may write to the Indian Patent Office to oppose the granting of a patent. The first kind, pre-grant opposition, may occur after the patent application has been published by the Patent Office, but has not yet been granted, for the primary purpose of challenging the application’s validity before a patent is granted. One may also give notice of opposition to the Patent Office after the granting of a patent, under post-grant opposition, so long as it occurs within a year of the granted patent’s publication.[25]

Compulsory Licensing

In March 2012, the Government of India granted its first compulsory license ever to Indian generic drug manufacturer, Natco Pharma Ltd. to allow for the manufacturing of Sorateni tosylate, a treatment for advanced kidney and liver cancer. Patent Holder and German pharmaceutical giant, Bayer Corporation, had not been making the drug adequately accessible to the people of India on a commercial scale, and had not imported the drug at all in 2008, and barely in 2009 and 2010. As a result, Natso Pharma Ltd. applied for a compulsory license.

Once granted, Natco was to pay a reduced royalty fee to Bayer quarterly, was required to provide the drug for free to at least 600 needy and deserving patients per year, to sell the drug for a set fee, as specified by the Indian government.

Pharmaceuticals have been an area of fierce debate as drugs for treating serious illnesses, such as malaria, HIV and AIDS, are widely available in the West, and generally too expensive for developing countries due to being protected by patents, where outbreaks are more likely to occur. India’s first compulsory license had been a landmark decision for India, as it is an exemplary case which demonstrates the possibility of a “new” drug under patent to be produced by generic makers at a fraction of the price, compensating the patent holder through royalty payments, while at the same time, enabling access to individuals that would not have otherwise been able to receive this form of treatment.

In the scenario where a government feels a patent holder is abusing one’s monopoly over their patented invention by excessively limiting others to access—and when it could otherwise substantially benefit the public good—a government may grant special privilege to another to use or manufacture such a patented product without the consent of its owner. This is called a compulsory license, and does not take the rights away from the patent holder, but limits them, as to enable increased access. A license fee or royalty payment is still to be paid to the patent holder; however this rate may be negotiated by the government, contrary to a statutory license, where this rate is fixed by the law.

Copyright

Copyright refers to the protection granted, in law, to the expression of some ideas. It is to be noted that the idea itself is not protectable. For instance, if I were to tell you about an ‘idea’ that I had about writing a story about a cat and a mouse, and, a few days later, you wrote a story about a cat and a mouse, the copyright of that story would vest with you, despite the fact that the ‘idea’ for the story was mine. This concept is called the idea-expression dichotomy.

The ‘expression’ that is eligible for protection could be in various forms, including literary, artistic or dramatic works.

Components of Copyright

Copyright recognises the concepts of ownership and authorship of work, and the fact that these might vary in specific instances, when various persons could be involved in the creation of a work. Some may have provided creative input (the author of the book or the director/screen play writer/story writer of the movie), and some may have provided monetary input (the publisher of the book/producer of the movie).

The moral right of ‘attribution’, that is, the right to be recognised for the work vests with the authors. Economic rights associated with copyright vest in the owner of the copyright. The owner could be different from the author. For instance, in case of the book, the owner of the copyright could be the publisher, and in the case of the movie, it could be the producer. In some instances, copyright may be jointly owned as well. Copyright vests in the owner of copyright. It grants the owner the right to exclude all others from making use of/exploiting the work in question commercially. This would essentially prevent others from adapting, copying, distributing, or making any other use of the protected work, unless authorised by the owner.

Copyright and the Law

Copyright law is territorial in nature, that is, copyright granted by law in one nation state is only enforceable in the said that grants the right. One aspect of territoriality could be the term of copyright. Generally, the term is the lifetime of the author (creator/owner) (plus) fifty to hundred years from the death of the author. Anonymous works, or works owned by corporations have a fixed term of copyright, usually between fifty and hundred years. The exception to this general rule of territoriality is if the state in question has entered into any international agreement to the contrary.

Other aspects of copyright regulated by law include subject matter of protection, requirements of registration, term of protection and associated rights. Internationally, the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, 1886 is the key instrument. Additionally, some other important international instruments include the WIPO Copyright Treaty, 1996 and the WIPO Performers and Phonograms Treaty, 1996.

While the general rule is that all copying and distribution of the copyrighted work has to be done with the express permission of the copyright holder, some exceptional circumstances allow for this requirement to be dispensed with. These are known as fair use/fair dealing (depending on the jurisdiction).

| Case Study: The Oxbridge Textbooks[26] |

|---|

|

The Broad Issue: The question then arises that how research that is carried out mostly with government funded public money be made available to the general public across the world at reasonable and affordable rates? Don’t students in the developing world have equal rights to access a level of education and research that would enable them to compete with their affluent counterparts? But this issue isn't just a cause for concern in the developing world as one of the world’s richest schools,Harvard University released a memorandum in mid-2012 that the cost of its journal subscriptions has become prohibitively expensive. This forces us to take a moment and think about the world of academic publishing, the accessibility of knowledge, and the flow of information when the richest academic institution on the planet cannot afford to continue paying for its journal subscriptions? According to Thomes and Clay’s report, commercial publishers within the last twenty to thirty years have taken control over many publications that had been controlled by non-profit academic and scholarly societies. The shift took place during the 1960’s and 1970’s as commercial publishers recognized the potential for profitability in acquiring journals from the societies. This has resulted in publishing houses now commanding hefty profit margins up to 40%. The Broad Solution: This clause can be challenged on the grounds of “fair use exception” under Section 52. The cancellation of these licenses is a fair demand as the risks of purchasing the license and complying to the publishing houses norms have many repercussions. Due to the business model of the publishing industry, a steep increase in prices has been seen for the past decade, the Harvard letter being just the tip of the iceberg. In 2012, over 12,000 researchers have signed a statement promising to boycott any publication published by Elsevier (a publication house accused of pocketing 40% of the profits). The increase in the prices of academic works in the international market has a steep impact on the budget of children who attend public universities such as Delhi University where the annual fees is Rs. 5000 per annum. Specific Issue at Hand: The specific issue here is a lawsuit filed by the Cambridge and Oxford publication press against Delhi University and a small photocopy shop for copyright infringement. The store, who they accuse of creating photocopied “course packs” in agreement with the University that include content from their textbooks, is selling these bundles for much cheaper than the original books. The presses are demanding more than US$110,000 in damages. On one hand we have powerful international publishing houses and on the other students who do not have access to study material from these houses due to their impoverished backgrounds. It is unlikely that the publishing houses’ revenues would increase post this suit, as most students cannot afford to purchase the study material unless the university foots the bill. It is also important to note that a previous lawsuit that Cambridge publication house lost was due to the defendant using only 10% of the book. In this case we have: Average percentage of entire book copied = 8.81 %. The breakup of the amount of material used per book can be found here.[28] Out of the 23 books in question, only 5 extracts exceed the 10% threshold(these have been marked in red in the document). To suggest that the photocopy shop and Delhi University should have to shell out Rs. 60,00,000 in damages for this case, is a case of publishing houses flexing their muscle power over students in the developing world who deserve equal access to academic material.

|

[1]. Peter Dravos

[2]. Ibid

[3]. Ibid

[4]. Ibid

[5]. For more on intellectual property see http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/intellectual-property/

[6]. Supra note above.

[7]. For more see Darryl J. Murphy “Are Intellectual Property rights compatible with Rawlsian principles of justice?, Springer, available at http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10676-012-9288-8

[8]. For more see Ashish Rajadhyaksha, “The Last Cultural Mile”, Centre for Internet and Society, available at http://cis-india.org/raw/histories-of-the-internet/last-cultural-mile.pdf, last accessed on February 1, 2014.

[9]. See citation above.

[10]. Geert Lovink and Nathaniel Tkacz, Critical Point of View: A Wikipedia Reader, published by CIS and Institute of Network Cultures, available at http://www.networkcultures.org/_uploads/%237reader_Wikipedia.pdf

[11]. The Access to Knowledge (Wikipedia) team from CIS has held several workshops and produced more than 50 blog entries in nearly 10 months.

[12]. See Pranesh Prakash, Nishant Shah, Sunil Abraham and Glover Wright, “Open Government Data Study: India” published by Transparency & Accountability Initiative, available at http://cis-india.org/openness/blog/publications/open-government.pdf

[13]. A term coined by the Brazilian theatre practitioner Augusto Boal in the context of theatre. This formulation of spect-actor is very useful in reimagining the citizen in the digital era that has created preconditions for the citizen to effectively participate in governance. For more on Spect-actor see Augusto, Boal (1993). Theater of the Oppressed. New York: Theatre Communications Group.

[14]. For more see Article 27 available at http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/index.shtml#a27, last accessed on January 31, 2014.

[15]. Read the full Covenant at https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%20999/volume-999-I-14668-English.pdf

[16]. Stephan Kinsella, “Against Intellectual Property”, Journal of Libertarian Studies 15, no. 2 (Spring 2001), available at http://www.stephankinsella.com/publications/against-intellectual-property/, last accessed on February 1, 2014.

[17]. See “Inventing the Funture: An Introduction to Patents for Small and Medium-sized Enterprises, World Intellectual Property Organization”, available at http://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/freepublications/en/sme/917/wipo_pub_917.pdf , last accessed on January 31, 2014.

[18]. See “Types of Patents”, available at http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/patdesc.htm , last accessed on January 31 , 2014

[19]. See “Inventions not Patentable in India”, available at http://www.cazri.res.in/itmu/pdf/Inventions%20not%20Patentable%20in%20India.pdf, last accessed on January 31, 2014.

[20]. Supra note 62 above.

[21]. See Research Proposal on Pervasive Technologies available at http://cis-india.org/a2k/pervasive-technologies-research-proposal.pdf , last accessed on January 31, 2014.

[22]. Ibid.

[23]. Ibid.

[24]. Ibid.

[25]. See Tech Corp Legal http://bit.ly/NBRg1F

[26]. Ariel Bogle, Cambridge & Oxford University Press sue Delhi University for copyright infringement — over course packs, March 18, 2013, Melville House, available at http://www.mhpbooks.com/cambridge-university-press-oxford-university-press-sue-delhi-university-for-copyright-infringement-over-course-packs/,last accessed on January 29, 2014.

[27]. http://www.irro.in/about.php

[28]. Book-wise Percentage Analysis (DU Photocopying Case), available at https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AnUBa-WkvhlOdDItVENnYkpZZ1ZYYTYwRGVycXVtZ1E#gid=0, last accessed on January 29, 2014.