Plugging into India’s broadband revolution

The article by Navadha Pandey was published in Livemint on June 4, 2019. Sunil Abraham was quoted.

All through 2018, 58-year-old Ashok Kumar Rai’s Lucknow-based small architecture firm used to spend a princely sum of ₹11,800 each month for the privilege of a good broadband internet connection. “We used to send building walk-through files to clients every day and the size of each file could go up to 1GB (gigabytes)," he says. Doling out cash for reliable internet was a necessity. All that changed when a new player, Atria Convergence Technologies Ltd (ACT), came to Rai’s upmarket Gomti Nagar neighbourhood in Lucknow. In the summer of 2019, Rai’s internet access speed has shot up from 4 to 150 Mbps (megabits per second). And the monthly bill has come crashing down to about ₹1,000.

For far too long, India’s internet action lay centered in its metros, leaving out even relatively big cities like Lucknow. The fledgling online access push into smaller cities and rural India happened primarily via mobile data transmitted over wireless spectrum. Home broadband was nowhere in the picture. But all that seems set for some dramatic change. If the country’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani, has his way, high-speed broadband will become a reality in at least 1,600 cities.

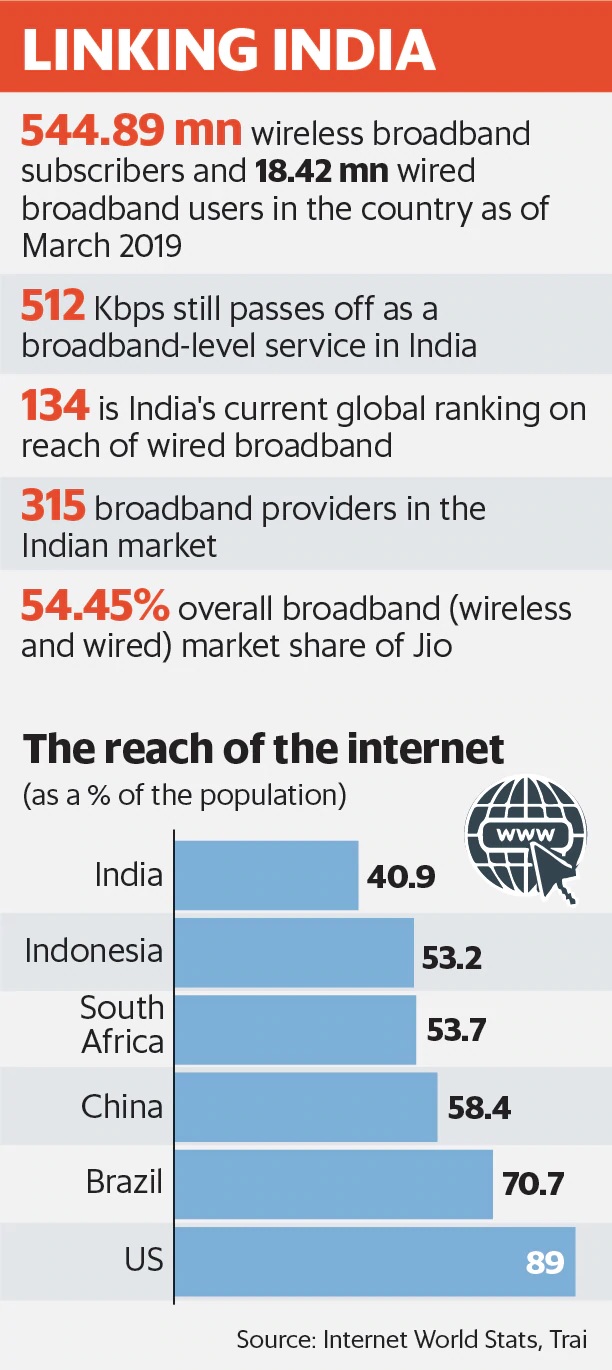

In the process, he aims to also leapfrog India from its current rank—134—in fixed-line broadband penetration to the top five with the help of Jio GigaFiber.

The dream of a broadband revolution, however, has its fair share of detractors. Bhaskar Ramamurthi, for example, who helms the Centre of Excellence in Wireless Technology (CWEiT at Indian Institute of Technology Madras (IIT Madras), says: “Fiber penetration will take a long time in India."

The logic is simple: unlike mobile towers, fiber needs to reach each home physically. China’s broadband boom happened because it has rebuilt nearly its entire housing stock in the last 15 years, fuelled by a construction-led growth bubble. “In India, initially only all the upcoming new buildings may get connected to fiber-based (fast) internet," says Ramamurthi.

But India’s untapped millions are about to set off a race. And this journey, which will clearly not be a cakewalk, has huge rewards in store. Sample this: India has 1.16 billion mobile subscribers but just 18.42 million wired broadband subscribers. And many of them, like Rai, are data hungry. There is an existing playbook: what happened to mobile broadband after 2014.

In 2014, the cost of one GB of mobile data was ₹270. Now, it is ₹10 per GB. As a result, mobile data consumption has soared. In late-2014, an average user on Airtel’s network (India’s largest telecom operator back then) used 622 megabytes (MB) of data in a month. By late-2018, the number of users had tripled, but, despite a broader base, average data usage stood at 10GB a month.

First-mover advantage

The expansion in wired broadband access may have far-reaching implications beyond a mere spike in data usage. When Mukesh Ambani, chairman and managing director of Reliance Industry Ltd which owns Reliance Jio Infocomm Ltd, declared optical fibre based fixed-line broadband as “the future" last July, the real play was not on the infrastructure itself, but the services that would ride on top—from smart home experiences to new forms of e-commerce. The revenue and the first-mover advantage lie in who gets to tap into the “ecosystem"—of how a household connects to the wider world to buy, watch, and exchange.

Essentially, new businesses could emerge to feed the “ecosystem". And some existing small and medium-scale businesses may finally become viable enough to expand and go big. Netflix, for example, emerged as one of the world’s largest video streaming platform, riding on top of the US broadband boom. But India already has a crowded pack of 34 web video streaming entertainment platforms, most of which have cropped up to sustain the attention of mobile data guzzling Indians. With wired broadband following mobile usage expansion, unlike in most other countries, India’s new-age internet businesses are likely to be unique and different.

Home-based surveillance and security systems could be one space that could gain significant traction, says Sunil Abraham, executive director of the Bengaluru-based think-tank Centre for Internet and Society. “If there are 40 families (in a high-rise apartment) who have babies and need surveillance facilities, each apartment going for an individual connection from a telecom service provider would involve a huge amount of money. But a fibre-based intranet or peer network could connect all 40 flats for a much smaller price," he says.

There could also be unintended consequences for the country’s digital gender divide. Only 29% of India’s current internet users are women, according to a recent Unicef report. If the cost of wired broadband begins to crash—thereby increasing the number of homes which have access—women who will never get access to a phone (due to the cost of device and patriarchy) will finally be able to see things on the internet, says Nandini Chami, a researcher at IT for Change, a non-governmental organization. “How this negotiation will happen inside the house, we will have to wait and watch," she says. Household-level access would also confuse corporate entities trying to “hyper-profile" users since multiple people will be accessing the internet through shared devices at home, she adds.

But as internet access improves, making the digital economy more vital, Chami says, governments would have an important role in ensuring women get to use the internet “on terms that are empowering". “We can think of innovative models when fixed broadband becomes cheap. The household is not the space for this. It can be libraries which have special times for young girls or digital labs for women. We need to rethink the missed opportunity of the BharatNet and the national optic fibre network. Internet access should not stop at just the panchayat office. We must think of different points of access, particularly for women," Chami adds.

The possibility of many of these radical changes in both the social and business realms will, of course, entirely rely on the pace at which India goes broadband. Despite the rapid expansion in mobile internet, data originating from mobile devices still account for only 20% of India’s data consumption. That is why what happens in the wired broadband space will matter increasingly. And that is also why Jio is betting big on expanding the existing wired user base (18 million) to 50 million.

The Jio gameplan

Jio is currently running beta trials for GigaFiber in New Delhi and Mumbai, providing 100GB of data at 100 Mbps for free, except for the ₹4,500 one-time deposit for a router. While the landline will come with unlimited calling facility, television channels will be delivered over the internet (Internet Protocol Television, or IPTV). The packaged trio of fast Internet, landline telephony, and television access will remain free for a while—similar to what had happened in the mobile phone services segment in 2016. After commercial launch, the per month cost is expected to be ₹600, roughly half of what similar services cost currently.

Jio’s rival Bharti Airtel Ltd has decided that it is not interested in the entire pie but just the creamy top layer. It will focus on premium customers and expand its broadband services across India’s top 100 cities, instead of copying Reliance Jio’s ambitious plan to create a fibre-optic network across the country. To achieve this, Airtel, which already has 2.36 million fibre customers, will stay focussed on high-rise buildings rather than horizontal deployment, as this business model is more economical and logical.

The dark horse in this race is, of course, ACT with its existing 1.42 million customers. Its presence is much smaller with just 18 cities, largely in the south India and the newly expanded zones of Delhi, Jaipur and Lucknow. On the ACT fibre network, average data consumption per user is already at 130GB a month.

“We have seen a 150% increase in average consumption in the last 18 months," says Bala Malladi, chief executive officer, ACT. “People are now looking at higher speeds and the experience is taking precedence over cost. In fact, even in the hinterland, people want higher speeds and non-buffered experience," he adds.

But why hasn’t fibre penetration gone up if the demand is booming? Why did India miss the bus when other countries like the US have an 80% fibre penetration?

Policy paralysis

Firstly, fibre is expensive to lay, unlike a SIM card which can be given away for free. Moreover, India till a few years ago was mostly a voice calls market and not a data market. Secondly, municipalities in India have complicated right-of-way (RoW) procedures which act as a big hurdle for digging and laying fibre. This is one of the reasons why even government (such as the Delhi government) plans to set up citywide surveillance and Wi-Fi hotspots have failed.

“The centre has finally issued a very good RoW model, but now every state has to come up with its own policy modelled on the central guidelines. They are taking their own sweet time," says Rajan Mathews, director general, Cellular Operators Association of India (COAI).

The lack of forward movement on these fixable policy issues assumes significance given the government’s focus on fibre in its National Digital Communications Policy-2018, which has a target of attracting $100 billion worth of investments in digital communications.

The policy’s goals include universal broadband for all, creating four million jobs in digital communications, and raising the share of digital communications in India’s gross domestic product (GDP) to 8% (from less than 6% in 2017). Deployment of five million public Wi-Fi hotspots by 2020 through a National Broadband Mission is also on the agenda. The key goal, however, is to provide 1 Gbps (gigabit per second) connectivity to all gram panchayats by 2020 and 10 Gbps by 2022.

The sad reality is that the last five years were an absolute failure in laying fibre in the country. BharatNet, the flagship mission to connect 250,000 gram panchayats with broadband, which was being implemented by Bharat Broadband Network Ltd (BBNL), a special purpose vehicle set up under the department of telecommunications (DoT) in February 2012, has been a disappointment, to say the least.

The government has completed laying optical fibre cables across more than 100,000 gram panchayats in the first phase and had aimed to complete connecting the remaining 150,000 councils by March 2019. The second phase has seen “zero progress", according to government officials close to the matter. Pained by poor utilization of digital infrastructure, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (Trai) suggested auctioning BharatNet infrastructure on an “as is where is" basis after a meeting held in December at the prime minister’s office to take stock of the mission.

To start with, the DoT plans to monetize fibre assets built by the government under its flagship mission BharatNet through outright sale to private players or by leasing these assets for a 20-year period after a bidding process. If successful, it could boost connectivity in Indian villages, which have so far been kept out of the digital dividend.

Bigger cities, however, will have a different consumption story. With intra-city fibre coverage leading to improved penetration, wired broadband would not just offer an enhanced content viewing experience, but also open doors for internet of things, or IoT. “Home security is going to become a big business going forward, riding on fibre. Even gaming will see a lot of traction as you can enjoy a 4K game in real-time, thanks to low latency and high speed of an optic network," Malladi of ACT says.

The looming question, however, is how much investment can operators put in given the current low tariff environment in the telecom sector. Big players are stressed for funds and are diluting their non-core assets to generate funds to keep networks afloat. “If you are looking at what will happen in the next three years... I believe that there is a business case to be made and tariffs should sustain it (the investment)," Mathews says.

Whether that happens or not could become an important footnote in India’s growth story. The far-reaching implications of fast internet access pushed billionaire tech entrepreneur Elon Musk, chief executive officer of Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (SpaceX), to launch 60 internet-beaming satellites last month. The grand scheme is a response to the practical constraint of laying fibre, a concern which is more pressing in India’s vast landmass.

Unlike Musk, the country’s broadband dreams, however, still remain rooted to the ground—in the simple tech of optic fibre. And the success or failure of those dreams will be written by how fast the fibre network expands.