From Open Citizen Radio Networks to the Race for .RADIO gTLD

On the afternoon of April 11, 2013, the president of the National University of Athens (NTUA) ,Simos Simopolous ordered the university’s Network Operations Centre (NOC) to pull the network plug off the IndyMedia Athens server that shared the university’s network infrastructure. With it went down the Internet radio stream of Radio98FM, an independent radio station broadcasting from within NUTA along with Radio Entasi. The takedown as it were later revealed, was an order by the Minister of Public Order, Nikos Dendias followed by the MP Adonis Georgiadis of the New Democracy Party tweeting in praise of the Minister’s decision. (Translate Tweet here : http://bit.ly/ZiBDuR ) Indymedia Athens still continues to be accessible through the Tor network at http://gutneffntqonah7l.onion/

The choice and use of broadcast networks in political and citizen uprisings have had a culturally specific side to it. The massive 2006 democracy movement in Nepal was fuelled entirely by pirate FM radio broadcasts, as most mountainous regions have no access to telephony, Internet or print news delivery services. Recently the world saw the power of social media , youtube and Twitter -- in Iran after the police killed student activist Neda and later in the landmark crisis of Tunisia.

By combining the power of seamless accessibility that the audio medium provides by allowing the user to multi-task, along with the viral broadcasting ability of the Internet, we indeed have an effective tool for networked citizen science. Are there popular models that the community can emulate, and what are the barriers to entry in a trans-medial paradigm such as Internet audio re-transmission?

An Overview of Open Radio Networks

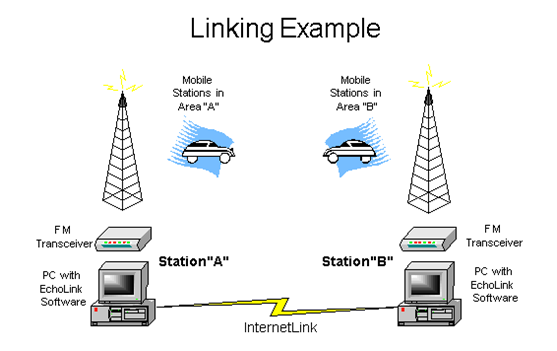

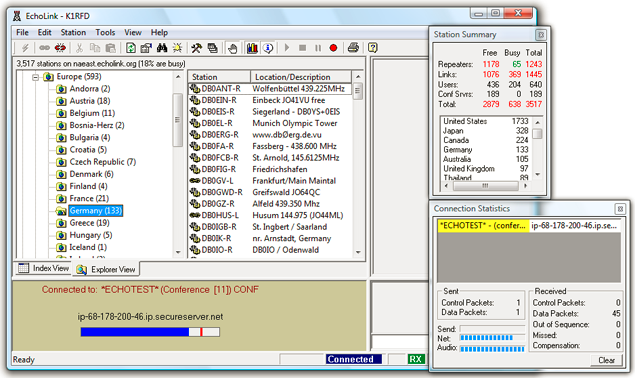

Let’s a take a quick peek into the wireless radio –VoIP service named ECHOLINK that I am fortunate to have had access to, over the last decade. Available to only ‘licensed’ and verified amateur radio operators, one maybe rest assured that strict legalities have unfortunately made such an open and transparent trans-medial global networked infrastructure impossible for commercial deployment or of use to the common citizen.

The ECHOLINK network was made possible thanks to the relentless efforts of amateur radio operators from around the world. It has enabled numerous wireless VHF local repeaters and links around the globe to be accessible over the Internet from practically any remote machine/device connected to the Internet, for both transmission as well as reception.

|

|---|

|

A memorable event was when I connected to a local Florida repeater from my bedroom’s PC and ended up conversing with an amateur radio operator who was driving around in his car through the Hurricane Katrina flooded streets with a VHF Handheld FM Transceiver, limited food supply and a gallon of reserve fuel canned in his backseat. Despite this, there was a sense of brethren and calm in his crackling radio voice that made it to the Florida repeater and then all the way to my home-station in Bangalore.

More recently, after the Fukushima Tsunami and Nuclear fallout, we observed that the Japanese government had jammed almost every radio repeater link, including the Emergency Amateur Radio service in Japan as they did not want any international contact to be made regarding the situation. Nevertheless after hours of trying, I intercepted a number of conference link nodes in Japan with people passing on information to each other about the deteriorating conditions in various prefectures. Below is a recorded excerpt from a conversation between two concerned citizens that I intercepted:

The Internet Radio Linking Project (IRLP) was a precursor to the Echolink network, invented by Dave Cameron (Callsign: VE7LTD) who installed the first three Windows O/S based IRLP nodes in Vancouver, British Columbia in 1997, followed by a more reliable Linux Node (VE7RHS) in 1998, after which the IRLP network soon spread worldwide. Amateur Radio operators with a VHF handheld transceiver and a custom (also DIY) IRLP interface hardware could connect to any local node within their RF Range and by using particular DTMF codes could establish a connection to any other node in the world by referring to a global list of node numbers. (http://status.irlp.net/).

ECHOIRLP enables Radio network node owners to support both IRLP as well as ECHOLINK networks on their repeater. A publically open trans-medial network such as this would certainly transform global information dissemination and accessibility, citizen journalism, community networks as well as disaster management.

Impedances and Emerging Trends in Commercial radio webcasting:

Similar radio network paradigms, albeit highly commercial, already exist within the mobile phone infrastructure, and with location-based services and audio databases like Spotify and audio detection apps like SoundHound on the rise, one could expect a huge boom in Internet radio services with contextual advertising on personal devices in the coming years. As with the press wars during the early 1930s in America, when newspapers viewed radio broadcasting as a formidable competitor, various impedances have kept Internet streaming away from the space that local wireless broadcasters and telecommunications networks have enjoyed for so long.

Unlike in the US or EU Copyright law, in India, there is currently no copyright law that clearly regulates Internet webcasting and radio retransmission on the Internet. In the United States however, webcasting of copyrighted audio content as well as internet retransmission of over-the air FM and AM radio broadcasts are subject to a per-performance royalty and an ‘ephemeral’ license fee. For the royalty calculations, transmission to each individual recipient is considered to be one ‘performance’. Estimating the market value of a ‘performance’ however is tricky, and the standing example that served as a reference, was the agreement reached between the RIAA (Recording Industry Association of America) that represents a majority of record labels that own copyrighted sound recordings and YAHOO! Inc , a then major webcaster and Internet re-transmitter. The RIAA-Yahoo! Agreement involved a lump sump payment of USD 1.25 million for the first 1.5 billion transmissions that amounted to about 0.08 cents/performance. The initial proposal by the CARP (Copyright Arbitration Royalty Panel) however, set this at 0.14 cents/performance for pure internet webcasts and 0.07 cents/performance for over-the air retransmissions, which later was rejected and equalized to 0.07cents/performance for both, after another recommendation by the Register of Copyrights was accepted by the Librarian of Congress.

In addition to this, an ephemeral license fee has to be paid by a webcaster and is currently set to be at about 8.8 per cent of the gross performance fee. ‘Ephemeral recordings’ in traditional broadcasting refer to the temporary copy made off a phono-record to facilitate transmission of the final studio mix. The twist in webcasting however is that temporary server copies necessary for Internet retransmission are subject to this ephemeral license fee.

Another limitation is bandwidth. Unlike wireless radio broadcasting that has a radial spread over line of sight depending on the wattage of transmission, the number of listeners that a server’s Internet radio streaming can tend to simultaneously, depends on the available bandwidth at the transmitting end. For instance, a 128kbps homebrew audio transmitted over a 1Mbps line using ShoutCast or Icecast, could probably support no more than 10 listeners although the advantage that listeners maybe geographically disparate cannot be overlooked.

The possibility of having a central webspace that provides access to streams of re-transmission of say, every FM news channel across the world still remains unfeasible. The logical next step would be to install multiple repeater servers that can access radio Internet servers located in different parts of the world retransmitting both commercial FM broadcasts as well as independent radio broadcasts, and constructed similar to the Echolink infrastructure. Ofcourse this would only be possible with a community-funded initiative led by the global amateur radio community in tandem with commercial pubic service broadcasters who agree to sacrifice on re-transmission royalties in view of mass accessibility. This collaboration now seems very possible with the latest .RADIO gTLD community based application that was filed by the EBU in 2013.

The .RADIO TLD competition

With ICANN launching the gTLD program, a notable contest has started for ownership of the .radio gTLD. The latest applicant is the Eurovision Broadcasting Union (EBU), the largest international association of broadcasters with supporters including the World Broadcasting Unions (WBU) and the Association Mondiale des Radiodiffuseurs Communautaires (AMARC). The EBU has filed for a ‘community based designation’ application, a move that has been actively supported by the International Amateur Radio Union (IARU), (http://goo.gl/H23YF), the founding fathers of the global amateur radio community. The European Broadcasting union, created in 1950, is a not-for-profit association and is one of the key sector members and technical advisors of the International Telecommunications Union. It’s primary function has been to advocate and negotiate the interests of European public broadcasters.

But three other standard applications for the .RADIO domain have been made to the ICANN as early as in 2012 by – BRS Media, AFILIAS and Tin Dale (LLC) all of whom have decried the latest application of EBU. BRS Media, as early as in 1998, entered into an ingenious agreement with the Federated States of Micronesia (country code .FM) and Armenia (country code .AM) and began offering the pricey .FM and .AM domains to Internet radio broadcasters and media services. AFILIAS Inc., who own the .MOBI and .INFO top level domains with it’s employees and investors in the ICANN Board have applied for 31 additional TLDs apart from .RADIO.

The ICANN reviews each applicant on the basis of descriptions of their mission and purpose of interest in the .RADIO TLD. While all the others allow ‘Open registrations’ of second level .RADIO domain-names by any organization, the EBU application entails a much more restrictive registration process where the initial round of registrations shall be limited to existing broadcasters, trademark owners, internet radio, amateur radio broadcasters and radio professionals.

The support of AMARC as well as the International Amateur Radio Union (IARU), (http://goo.gl/H23YF), has helped EBU to fulfill ICANN’s important pre-requisites for a community-based TLD application – that is “to substantiate its status as representative of the community it names in application by submission of written endorsements in support of the application.”

Does this mean that we shall finally see the dawn of widely accessible Internet radio and digital re-transmissions of over the air broadcasts, with the amateur radio networks working in tandem with commercial public service broadcasters? Will the EBU truly be a representative of the global broadcasting community and will it treat US counterparts no different from EU and rest of the world? And finally, what impact shall all this have on Internet governance, dissemination of public opinion and citizen interventions? These are but some of the burning questions that shall surface in the near future.

Key References

- http://www.echolink.org

- http://www.irlp.net/

- Summary of the Determination of the Librarian of Congress on Rates and Terms for Webcasting and Ephemeral Recordings (http://goo.gl/xPEj8)

- http://newgtlds.icann.org/en/

- http://www.arrl.org/