Blog

Presentation on MLATS

Presentation on MLATS-1.pdf

—

PDF document,

313 kB (321475 bytes)

Presentation on MLATS-1.pdf

—

PDF document,

313 kB (321475 bytes)

Internet-driven Developments — Structural Changes and Tipping Points

The symposium served as an inaugural event for the Global Network of Interdisciplinary Centers, which currently includes as its members:

- The Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University

- The Alexander von Humboldt Institute for Internet & Society

- The Centre for Internet and Society, Bangalore

- The Center for Technology & Society at the Fundacao Getulio Vargas Law School, Keio University

- The MIT Media Lab and its Center for Civic Media

- The NEXA Center for Internet & Society at Politicnico di Torino.

Individuals and researchers from the Centers focused on understanding the effects of internet and society. The participants were brought together to explore the past, present, and future tipping points of the internet, to identify knowledge gaps, and to find areas of collaboration and future action between institutes and individuals. Specifically, the symposium set out to examine fundamental questions about the internet, identify structural changes that are occurring because of the internet, and the forces that are catalyzing these changes. Questions asked and discussed included:

- What forces are changing production and service models?

- What forces are influencing entrepreneurship and innovation? and

- What forces are changing political participation?

Production and Service Models

Discussion

When participants discussed the changes that are happening to production and service models, concepts such as big data, algorithms, peer based models of production, and intermediaries were identified as actors and tools that are driving change in production and service models in the context of the internet. For example, big data and algorithms are being used to alter the nature, scope, and reach of business by allowing for the personalization and customization of services. To this end, many organizations have incorporated customer participation into business models, and provide platforms for feedback and input. The personalization of services has placed greater emphasis on the voice of the customer, allowing customers to guide and influence business by voicing preferences, satisfaction levels, etc. In this way, consumers can determine what type of service they want, and can also make political statements through their choices and feedback. In the process, however, such platforms generate and depend on large amounts of data and thus raise concerns about privacy.

Knowledge gaps that were identified during the conversation included how to predict what would make a participatory platform and peer based model successful, and how these platforms can be effectively researched. When looking at big data, a knowledge gap that was identified included how to ensure that data are collected ethically and accurately, as well as the related question: once large data sets are collected, how can the data be analyzed and used in a meaningful way?

There was also discussion about the increasingly critical and powerful role that intermediaries serve within the scope of the internet as they act as the platform provider and regulator for internet content. Intermediaries both allow for content to be posted on the internet, and determine what information is accessed through the filtering of web searches. Increasingly, governments are seeking to regulate intermediaries and create strict rules of compliance with governmental mandates. At the same time governments are placing the responsibility and liability of regulating what content is posted on internet on intermediaries, essentially placing them in the role of an adjudicator. This is one example of how the relationship between the private sector, the government, and the individual is changing, because it is only recently that private intermediaries have been held responsible first to governments, and only secondarily to customers.

Knowledge gaps identified in the discussion on intermediaries included understanding and researching how intermediaries decide to filter content found through searches. On what basis is each filter done? Are there actors influencing this process? And what are the economics behind the process?

Personal Thoughts

When reflecting on how the internet is changing and influencing the production of goods and services, I personally would add to the points discussed in the meeting the fact that the internet has also impacted the job economy. Reports show that jobs in the extraction and manufacturing sector are decreasing, as the internet has created a mandatory new tech oriented skill set that often outweighs the need for other skill sets. This change is far reaching as the job economy influences what skills students choose to learn, why and for what purposes individuals migrate across borders for employment, and in what industries governments invest money towards domestic development. In addition to changing the nature of skills in demand, the nature of the services themselves is changing. Though services are becoming more personalized and tailored to the individual, this personalization is automated, and replacing the ‘human touch’ that was once prized in business. Whether customers care if the service they are given is generated by an algorithm or delivered by an individual may depend on a person’s preference, but the European Union has seen this shift as being significant enough to address automated decision making in Article 15 of the EU directive, which provides individuals the right to not be subject to a decision which legally impacts him/her which is based only on automated processing of data. This directive encompasses decisions such as evaluation of a person’s performance at work, creditworthiness, reliability, conduct, etc.

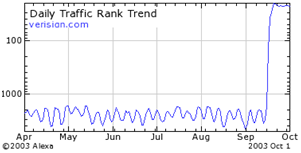

The internet has also increased the cost of small mistakes made by businesses, as any mistake will now potentially impact millions of customers. The impact of any mistake makes risk management much more important and difficult, as businesses must seek to anticipate and mitigate any and all mistakes. The internet has also created a new level of dependency on the network, as businesses shift all of their services and functions over to the internet. Thus, if the network goes down, businesses will lose revenue and customers. This level of dependency on the network that exists today is different from past reliance’s on technology — in the sense that in the past there was not one single type of technology that would be essential for many businesses to run. The closest analogue was transportation: if trucks, trains, or ships were unavailable, multiple industries would be impacted. The difference is that those who relied on rail could shift temporarily to ships or trucks. Those relying on the network have no alternatives. Furthermore, past technologies were constantly evolving in the resources they depended on — from coal to gas, etc, but for the internet, it seems that the resource is not evolving, so much as expanding as increased bandwidth and connectivity are the solution to allowing technological evolution and innovation through the internet.

As discussed above, intermediaries are becoming key and powerful players, but they also seem to be increasingly placed between a rock and a hard place, as governments around the world are asking national and multinational intermediaries to filter content that violates national laws in one context, but not another context. Furthermore, intermediaries are increasingly being asked to comply with law enforcement requests for access to data that is often not within the jurisdiction of the requesting country. The difficult position intermediaries are placed in demonstrates how the architecture of the internet is borderless but the regulation and use of the internet is still tied to borders and jurisdiction.

Entrepreneurship and Innovation

Discussion

When discussing entrepreneurship and innovation it was pointed out by participants that grey markets and market failures are important indicators for possibilities of new business models and forms of innovation. Because of that, it is important to study what has failed and why when identifying new possibilities and trends. The importance of policies and laws that allow for innovation and entrepreneurship was also highlighted.

Personal Thoughts

When thinking about entrepreneurship and innovation on the internet and forces driving them, it seems clear that tethering, conglomerating, and organizing information from multiple sources is one direction that innovation is headed. Services are coming out that have the ability to search the internet based on individual preferences and provide more accurate data quickly. This removes the need for individuals to search the internet at length to find the information or products they want. Along the same lines, it seems that there is a greater trend towards personalization. Services are finding new and innovative ways to bring individuals customized products. Another trend is the digitization of all services — from moving libraries online, to bookstores online, to grocery stores online. Lastly, there is a constant demand for new applications to be developed. These can range from applications enabling communication through social networking, to applications that act as personal financial consultants, to applications that act as personal trainers. The ability for concepts, trends, etc to go viral on the internet has also added another dimension to entrepreneurship and innovation as any individual can potentially become successful by something going viral. The ability for something to go viral on the internet does not just impact entrepreneurship and innovation, but also impacts political participation and production and service models.

Political Participation

Discussions also centered on how political participation is changing as the internet is being used as a new platform for participation. For example, it is now possible for individuals to leverage their voice and message to local and global communities. Furthermore, this message can be communicated on a seemingly personal scale. Individuals from one community are able to connect to communities from another location — both local and abroad, and to work together to catalyze change. Messages and communications can be spread easily to millions of people and can go viral. This ability has changed and created new public spheres, where anyone can contribute to a dialogue from anywhere. Empowerment is shifting as well, because the internet allows for new power structures to be created by any actor who knows how to leverage the network. These factors allow for more voices to be heard and for greater citizen participation. The role of the youth in political movements was also emphasized in the discussions. On the other hand governments have responded by more heavily regulating speech and content on the internet when dissenting voices and campaigns are seen as a threat. It was also brought out that though emerging forms of online political participation have been heralded by many for achievements such as facilitating democracy, transparency, and bringing a voice to the silenced — many have warned that analysis of these political forms of participation overlook individual contributions and time. Other critiques that were discussed included the fact that digital revolutions also exclude individuals who do not have access to the internet or to platforms/applications and overlook actions and movements that take place offline.

Knowledge gaps that were identified included understanding the basics of the change that is happening in political participation through the internet. For example, it is unclear who the actors are that determine the conditions and scope for these changes, and like participatory forms of business, what enables and mobilizes change. Furthermore, it is unclear who specifically benefits from these changes and how, and who participates in the changes — and in what capacity. Additionally, much of the change has been quantified in the dialogue of the ‘global’ — global voices, global movements — but that dialogue ignores the local.

Personal Thoughts

In addition to the discussions on political participation, I believe the internet has created the possibility for ‘social governance’. To address situations in which there is no particular law against an action, but individuals come together and speak out against actions that they see on the internet that they believe should be stopped or changed. Depending on the extent individuals choose to enforce these decisions, this can be potentially dangerous as individuals are essentially rewriting laws and social norms without subjecting them to the crucible of consensus decision-making or review. In addition, forms of political participation are not changing just in terms of how the individual engages politically with states and governments, but also in the ways that politicians are engaging with citizens. For example, politicians are using Facebook and Twitter as means to communicate and gather feedback from supporters. Politicians are also using technology to reach more individuals with their messages — from experimenting with 3D holograms, to web casting, to using technology like CCTV cameras to prove transparency. The impact of this could be interesting, as technology is becoming a mediating tool that works in both directions between citizens and governments. Is this changing the traditional understandings of the State and the relationship between the State and the citizen?

Conclusion and ways forward

The discussions also pulled out dichotomies that apply to the internet and illustrate tensions arising from different forces. These dichotomies can be shaped by individuals and actors attempting to regulate the internet, as for example with new models of regulation vs. old models of regulation, private vs. public, local vs. global, owned vs. unowned, and zoned vs. unzoned. These dichotomies can be shaped by how the internet is used. For example, fair vs. unfair, just vs. unjust, represented vs. silenced, and uniform vs. diverse.

Common questions being asked and areas for potential research that came out of these discussions included information communication and media, how to address different and at times contradictory policies and levels of development in different countries, and what is the impact of big data on different sectors and industries like e-health and journalism? What is the importance of ICT in creating economic progress? How is the Internet changing the nature of democracy?

When discussing ways forward and areas for future collaboration it was brought out that exploring ways to leverage open data, ways to effectively use and build off of perspectives and experiences from other contexts and cultures, and ways to share resources across borders including funding, human presence, and expertise were important questions to answer. Common challenges that were identified by participants ranged from cyber security and the rise of state and non-state actors in cyber warfare, finding adequate funding to support research, sustaining international collaborations, ensuring that research is meaningful and can translate into useful resources for policy and law makers, and ensuring that projects are designed with a long-term objective and vision in mind.

The discussions, presentations, and contributions by participants during the two day symposium were interesting and important as they demonstrated just how multi-faced the internet is, and how it is never one dimensional. How the internet is researched, how it is used, and how it is regulated will be constantly changing. Whether this change is a step forward, or a re-invention of what has already been done, is up to all who use the internet including the individual, the corporation, the researcher, the policy maker, and the government.

The Worldwide Web of Concerns

Pranesh Prakash's column was published in the Deccan Chronicle on December 10, 2012.

Much has changed since the 1988 Melbourne conference. Since 1988, mobile telephony has grown by leaps and bounds, the Internet has expanded and the World Wide Web has come into existence.

Telecommunications is now, by and large, driven by the private sector and not by state monopolies.

While there are welcome proposals (consumer protection relating to billing of international roaming), there have also been contentious issues that Internet activists have raised: a) process-related problems with the ITU; b) scope of the ITRs, and of ITU’s authority; c) content-related proposals and “evil governments” clamping down on free speech; d) IP traffic routing and distribution of revenues.

Process-related problems: The ITU is a closed-door body with only governments having a voice, and only they and exorbitant fees-paying sector members have access to documents and proposals. Further, governments generally haven’t held public consultations before forming their positions. This lack of transparency and public participation is anathema to any form of global governance and is clearly one of the strongest points of Internet activists who’ve raised alarm bells over WCIT.

w Scope of ITRs: Most telecom regulators around the world distinguish between information services and telecom services, with regulators often not having authority over the former. A few countries even believe that the wide definition of telecommunications in the ITU constitution and the existing ITRs already covers certain aspects of the Internet, and contend that the revisions are in line with the ITU constitution. This view should be roundly rejected, while noting that there are some legitimate concerns about the shift of traditional telephony to IP-based networks and the ability of existing telecom regulations (such as those for mandatory emergency services) to cope with this shift.

ITU’s relationship with Internet governance has been complicated. In 1997, it was happy to take a hands-off approach, cooperating with Internet Society and others, only to seek a larger role in Internet governance soon after. In part this has been because the United States cocked a snook at the ITU and the world community in 1998 through the way it established Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) as a body to look after the Internet’s domain name system. While the fact that the US has oversight over ICANN needs to change (with de-nationalisation being the best option), Russia wants to supersede ICANN and that too through current revisions of the ITRs. Russia’s proposal is a dreadful idea, and must not just be discarded lightly but thrown away with great force. The ITU should remain but one among multiple equal stakeholders concerned with Internet governance.

One important, but relatively unnoticed, proposed change to ITU’s authority is that of making the standards that ITU’s technical wing churns out mandatory. This is a terrible idea (especially in view of the ITU’s track record at such standards) that only a stuffy bureaucrat without any real-world insight into standards adoption could have dreamt up.

Content-related proposals: Internet activists, especially US-based ones, have been most vocal about the spectre of undemocratic governments trying to control online speech through the ITRs. Their concerns are overblown, especially given that worse provisions already exist in the ITU’s constitution. A more real threat is that of increasing national regulation of the Internet and its subsequent balkanisation, and this is increasingly becoming reality even without revisions to the ITRs.

Having said that, we must ensure that issues like harmonisation of cyber-security and spam laws, which India has been pushing, should not come under ITU’s authority. A further worry is the increasing militarisation of cyberspace, and an appropriate space must be found by nation-states to address this pressing issue, without bringing it under the same umbrella as online protests by groups like Anonymous.

Division of revenue: Another set of proposals is being pushed by a group of European telecom companies hoping to revive their hard-hit industry. They want the ITU to regulate how payments are made for the flow of Internet traffic, and to prevent socalled “net neutrality” laws that aim to protect consumers and prevent monopolistic market abuse. They are concerned that the Googles and Facebooks of the world are free-riding on their investments. That all these companies pay to use networks just as all home users do, is conveniently forgotten. Thankfully, most countries don’t seem to be considering these proposals seriously.

Can general criteria be framed for judging these proposals? In submissions to the Indian government, the Centre for Internet and Society suggested that any proposed revision of the ITRs be considered favourably only if it passes all the following tests: if international regulation is required, rather than just national-level regulation (i.e., the principle of subsidiarity); if it is a technical issue limited to telecommunications networks and services, and their interoperability; if it is an issue that has to be decided exclusively at the level of nation-states; if the precautionary principle is satisfied; and if there is no better place than the ITRs to address that issue. If all of the above are satisfied, then it must be seen if it furthers substantive principles, such as equity and development, competition and prevention of monopolies, etc. If it does, then we should ask what kind of regulation is needed: whether it should be mandatory, whether it is the correct sort of intervention required to achieve the policy objectives.

The threat of a “UN takeover” of the Internet through the WCIT is non-existent. Since the ITU’s secretary-general is insisting on consensus (as is tradition) rather than voting, the possibility of bad proposals (of which there are many) going through is slim. However, that doesn’t mean that activists have been crying themselves hoarse in vain. That people around the world are a bit more aware about the linkage between the technical features of the Internet and its potential as a vehicle for free speech, commerce and development, is worth having to hear some shriller voices out there.

The writer is policy director at the Centre for Internet and Society, Bengaluru

Tomorrow, Today

Nishant Shah's end of the year column was published in the Indian Express on December 29, 2012.

And I find myself in a similar frame of mind, celebrating with joy the promises that were kept, reflecting sombrely on the opportunities we missed, and speculating about what the new year is going to bring in for the future of digital and internet technologies, and how they are going to change the ways in which we understand what it means to be human, to be social, and to be the political architects of our lives.

We all know that dramatic change is rare. Nothing transforms overnight, and a lot of what we can look forward to in the next year, is going to be contingent on how we have lived in this one. And yet, the rapid pace at which digital technologies change and morph, and the ways in which they produce new networked conditions of living, make it worthwhile to speculate on what are the top five things to look out for in 2013, when it comes to the internet and how it is going to affect our techno-social lives.

Head in the Cloud

If the last year was the year of the mobile, as more and more smartphones started penetrating societies, providing new conditions of portable and easy computing, making ‘app’ the word of the year, then the next year definitely promises to be the year of the cloud. As internet broadband and mobile data access become affordable, increasingly we are going to see services that no longer require personal computing power. All you will need is a screen and a Wi-Fi connection and everything else will happen in the cloud. No more hard drives, no more storage, no more disconnectivity, and data in the cloud.

More Talk

One of the biggest problems with the internet has been that it has been extremely text heavy. We often forget that the text is still a matter of privilege as questions of illiteracy and translation still hound a large section of the global population. However, with the new protocols of access, availability of 4G spectrum and the release of IPV6 as the new standard, we can expect faster voice and video-based communication at almost zero costs. It might be soon time to say goodbye to the SMS.

Big Data

You think you are suffering from information overload now? Wait for the next year as mobile and internet penetration are estimated to rise by 30 per cent around the world! This is going to be the year of Big Data — data so big that it can no longer be fathomed or understood by human beings. We will be dependent on machines to read it, process it, and show us patterns and trends because we are now at a point in our information societies where we are producing data faster than we can process it. Our governments, markets and societies are going to have to produce new ways of governing these data landscapes, leading to dramatic changes in notions of privacy, property and safety.

No Next Big Thing

If you haven’t noticed it, the pace of dramatic innovation has slowed down in the last few years and it will slow down even more. We have been riding the wave of the next big thing, in the last few years, constantly in search of new gadgets, platforms and ways of networking. However, the coming year is going to make innovation granular. It will be a year where things become better, and innovation happens behind the scene. So if you thought this was the year that Facebook will finally become obsolete and something else will take over, you might want to reconsider deleting your account, and start looking at the changes that shall happen behind the scenes, for better or for worse.

The Return of the Human

The rise of the social network has distracted us from looking at the human conditions. We have been so engaged in understanding friendship in the time of Facebook, analysing relationships, networked existences and our own performance as actors of information, that we haven’t given much thought to what it means to be human in our rapidly digitising worlds. And yet, the revolutions and the uprisings we have witnessed have been about people using these social networks to reinforce the ideas of equity, justice, inclusion, peace and rights across the world. As these processes strengthen and find new public spaces of collaboration, we will hopefully see social and political movements which reinforce, that at the end of the day, what really counts, is being human.

The future, specially in our superconnected times, is always unpredictable. But the rise of digital technologies has helped us revisit some of the problems that have been central to a lot of emerging societies — problems of inequity, injustice, violence and violation of rights. And here is hoping that the tech trends in the coming year, will be trends that help create a better version of today, tomorrow.

State Surveillance and Human Rights Camp: Summary

This research was undertaken as part of the 'SAFEGUARDS' project that CIS is undertaking with Privacy International and IDRC.

The camp also examined different types of data, understanding tools that governments can use to access data, and looked at examples of surveillance measures in different contexts. The camp was divided into plenary sessions and individual participatory workshops, and brought together activists, researchers, and experts from all over the world. Experiences from multiple countries were shared, with an emphasis on the experience of surveillance in Latin America. Among other things, this blog summarizes my understanding of the discussions that took place.

The camp also served as a platform for collaboration on the Draft International Principles on Communications Surveillance and Human Rights. These principles seek to set an international standard for safeguards to the surveillance of communications that recognizes and upholds human rights, and provide guidance for legislative changes related to communications and communications meta data to ensure that the use of modern communications technology does not violate individual privacy. The principles were first drafted in October 2012 in Brussels, and are still in draft form. A global consultation is taking place to bring in feedback and perspective on the principles.

The draft principles were institutionalized for a number of reasons including:

- Currently there are no principles or international best standards specifically prescribing necessary and important safeguards to surveillance of communication data.

- Practices around surveillance of communications by governments and the technology used by governments is rapidly changing, while legislation and safeguards protecting individual communications from illegal or disproportionate surveillance are staying the same, and thus rapidly becoming outdated.

- New legislation that allows surveillance through access to communication data that is being proposed often attempts to give sweeping powers to law enforcement for access to data across multiple jurisdictions, and mandates extensive cooperation and assistance from the private sector including extensive data retention policies, back doors, and built in monitoring capabilities.

- Surveillance of communications is often carried out with few safeguards in place including limited transparency to the public, and limited forms of appeal or redress for the individual.

This has placed the individual in a vulnerable position as opaque surveillance of communications is carried out by governments across the world — the abuse of which is unclear. The principles try to address these challenges by establishing standards and safeguards which should be upheld and incorporated into legislation and practices allowing the surveillance of communications.

A summary of the draft principles is below. As the principles are still a working draft, the most up to date version of the principles can be accessed here.

Summary of the Draft International Principles on Communications Surveillance and Human Rights

Legality: Any surveillance of communications undertaken by the government must be codified by statute.

Legitimate Purpose: Laws should only allow surveillance of communications for legitimate purposes.

Necessity: Laws allowing surveillance of communications should limit such measures to what is demonstrably necessary.

Adequacy: Surveillance of communications should only be undertaken to the extent that is adequate for fulfilling legitimate and necessary purposes.

Competent Authority: Any authorization for surveillance of communications must be made by a competent and independent authority.

Proportionality: All measures of surveillance of communications must be specific and proportionate to what is necessary to achieve a specific purpose.

Due process: Governments undertaking surveillance of communications must respect and guarantee an individual’s human rights. Any interference with an individual's human rights must be authorized by a law in force.

User notification: Governments undertaking surveillance of communications must allow service providers to notify individuals of any legal access that takes place related to their personal information.

Transparency about use of government surveillance: The governments ability to survey communications and the process for surveillance should be transparent to the public.

Oversight: Governments must establish an independent oversight mechanism to ensure transparency and accountability of lawful surveillance measures carried out on communications.

Integrity of communications and systems: In order to enable service providers to secure communications securely, governments cannot require service providers to build in surveillance or monitoring capabilities.

Safeguards for international cooperation: When governments work with other governments across borders to fight crime, the higher/highest standard should apply.

Safeguards against illegitimate access: Governments should provide sufficient penalties to dissuade against unwarranted surveillance of communications.

Cost of surveillance: The financial cost of the surveillance on communications should be borne by the government undertaking the surveillance.

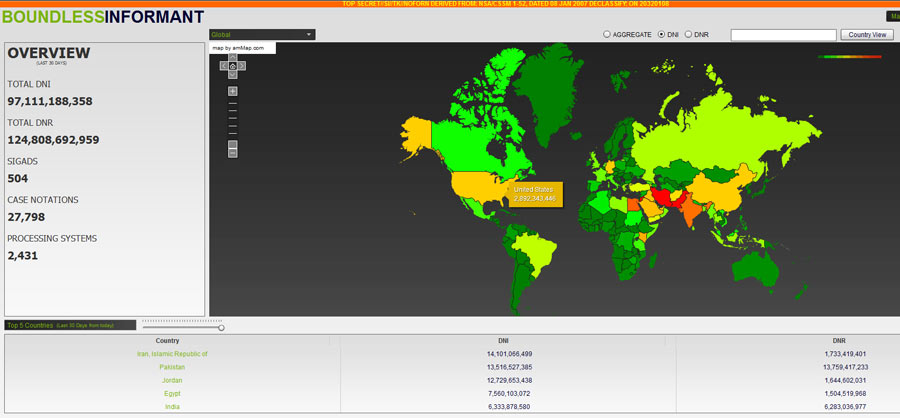

Types of Data

The conversations during the camp reviewed a number of practices related to surveillance of communications, and emphasized the importance of establishing the draft principles. Setting the background to various surveillance measures that can be carried out by the government, the different categories of communication data that can be easily accessed by governments and law enforcement were discussed. For example, law enforcement frequently accesses information such as IP address, account name and number, telephone number, transactional records, and location data. This data can be understood as 'non-content' data or communication data, and in many jurisdictions can easily be accessed by law enforcement/governments, as the requirements for accessing communication data are lower than the requirements for accessing the actual content of communications. For example, in the United States a court order is not needed to access communication data whereas a judicial order is needed to access the content of communications.[1]

Similarly, in the UK law enforcement can access communication data with authorization from a senior police officer.[2]

It was discussed how it is concerning that communication data can be accessed easily, as it provides a plethora of facts about an individual. Given the sensitivity of communication data and the ability for personal information to be derived from the data, the ease that law enforcement is accessing the data, and the unawareness of the individual about the access- places the privacy of users at risk.

Ways of Accessing Data

Ways in which governments and law enforcement access information and associated challenges was discussed, both in terms of the legislation that allows for access and the technology that is used for access.

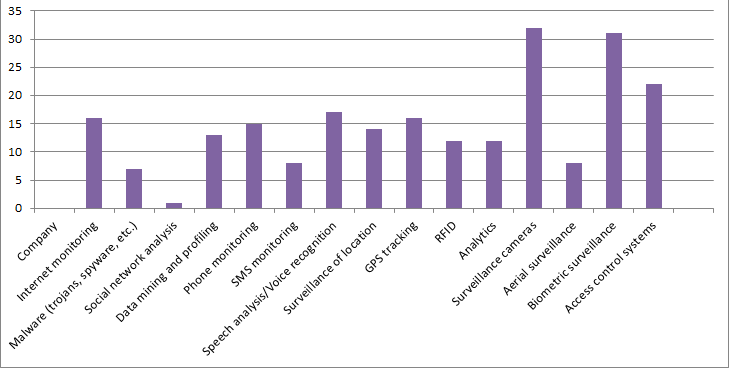

Access and Technology

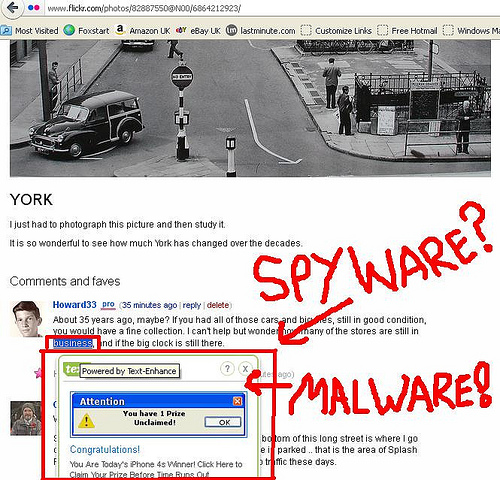

In this discussion it was pointed out that in traditional forms of accessing data governments are no longer effective for a number of reasons. For example, in many cases communications and transactions, etc., that take place on the internet are encrypted. The ubiquitous use of encryption means more protection for the individual in everyday use of the internet, but serves as an obstacle to law enforcement and governments, as the content of a message is even more difficult to access. Thus, law enforcement and governments are using technologies like commercial surveillance software, targeted hacking, and malware to survey individuals. The software is sold off the shelf at trade shows by commercial software companies to law enforcement and governments. Though the software has been developed to be a useful tool for governments, it was found that in some cases it has been abused by authoritarian regimes. For example in 2012, it was found that FinSpy, a computer espionage software made by the British company Gamma Group was being used to target political dissidents by the Government of Bahrain. FinSpy has the ability to capture computer screen shots, record Skype chats, turn on computer cameras and microphones, and log keystrokes.[3]

In order to intercept communications or block access to sites, governments and ISPs also rely on the use of deep packet inspection (DPI).[4] Deep packet inspection is a tool traditionally used by internet service providers for effective management of the network. DPI allows for ISP's to monitor and filter data flowing through the network by inspecting the header of a packet of data and the content of the packet.[5] With this information it is possible to read the actual content of packets, and identify the program or service being used.[6]

DPI can be used for the detection of viruses, spam, unfair use of bandwidth, and copyright enforcement. At the same time, DPI can allow for the possibility of unauthorized data mining and real time interception to take place, and can be used to block internet traffic whether it is encrypted or not.[7]

Governmental requirements for deep packet inspection can in some cases be found in legislation and policy. In other cases it is not clear if it is mandatory for ISP's to provide DPI capabilities, thus the use of DPI by governments is often an opaque area. Recently, the ITU has sought to define an international standard for deep packet inspection known as the "Y.2770" standard. The standard proposes a technical interoperable protocol for deep packet inspection systems, which would be applicable to "application identification, flow identification, and inspected traffic types".[8]

Access and Legislation

The discussions also examined similarities across legislation and policy which allows governments legal access to data. It was pointed out that legislation providing access to different types of data is increasingly becoming outdated, and is unable to distinguish between communications data and personal data. Thus, relevant legislation is often based on inaccurate and outdated assumptions about what information would be useful and what types of safeguards are necessary. For example, it was discussed how US surveillance law has traditionally established safeguards based on assumptions like: surveillance of data on a personal computer is more invasive than access to data stored in the cloud, real-time surveillance is more invasive than access to stored data, surveillance of newer communications is more invasive than surveillance of older communications, etc. These assumptions are no longer valid as information stored in the cloud, surveillance of older communications, and surveillance of stored data can be more invasive than access to newer communications, etc. It was also discussed that increasingly relevant legislation also contains provisions that have generic access standards, unclear authorization processes, and provide broad circumstances in which communication data and content can be accessed. The discussion also examined how governments are beginning to put in place mandatory and extensive data retention plans as tools of surveillance. These data retention mandates highlight the changing role of internet intermediaries including the fact that they are no longer independent from political pressure, and no longer have the ability to easily protect clients from unauthorized surveillance.

1]. EFF. Mandatory Data Retention: United States. Available at: https://www.eff.org/issues/mandatory-data-retention/us

[2].Espiner, T. Communications Data Bill: Need to Know. ZDNet. June 18th 2012. http://www.zdnet.com/communications-data-bill-need-to-know-3040155406/

[3]. Perlroth, M. Software Meant to Fight Crime is Used to Spy on Dissidents. The New York Times. August 30th 2012. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/31/technology/finspy-software-is-tracking-political-dissidents.html?_r=0

[4]. Wawro, A. What is Deep Packet Inspection?. PCWorld. February 1st 2012. Available at: http://www.pcworld.com/article/249137/what_is_deep_packet_inspection_.html

[5]. Geere, D. How deep packet inspection works. Wired. April 27th 2012. Available at: http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2012-04/27/how-deep-packet-inspection-works

[6]. Kassner. M. Deep Packet Inspection: What You Need to Know. Tech Republic. July 27th 2008. Available at: http://www.techrepublic.com/blog/networking/deep-packet-inspection-what-you-need-to-know/609

[7]. Anonyproz. How to Bypass Deep Packet Inspection Devices or ISPs Blocking Open VPN Traffic. Available at: http://www.anonyproz.com/supportsuite/index.php?_m=knowledgebase&_a=viewarticle&kbarticleid=138

[8].Chirgwin. R. Revealed: ITU's deep packet snooping standard leaks online: Boring tech doc or Internet eating monster. The Register. December 6th 2012. Available at: http://www.theregister.co.uk/2012/12/06/dpi_standard_leaked/

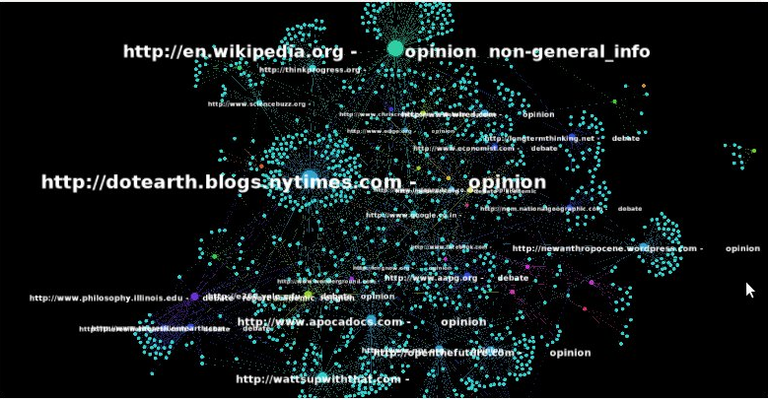

Mining the Web Collective

While the context of this workshop focussed on deciphering and mapping opinions related to academic controversies surrounding climate change, the very same techniques of deploying digital tools to crawl through associated content on the websphere, maybe used to map any other controversy that has been actively influencing public and political opinion.

As one of the participants in the workshop, in an attempt to make my interpretation as accessible as possible to a wider inter-disciplinary audience, below is my own assimilation and extrapolation of the musings and discussions that entailed. Further I have drawn out limitations and future directions towards more viable paradigms that augment the mapping and democratization of public opinion.

The session drew an outset around how new digital tools could aid researchers by enabling them to quickly see an individual entity’s data as well as it’s associated aggregates, and register all of this within a single view in real-time. Contrasting the traditional methods of data collection through individual surveys, new digital methods can almost instantaneously bridge the gap between the individual and the collective and help us answer the question that Latour poses in his most recent paper that revisits social theory around the Tardean concept of reciprocally connected ‘monads’ -- ''.... is there an alternative to the common sense version that distinguishes atoms, interactions and wholes as successive sequences (whatever the order and the timing)? An alternative that should not oblige the inquirer to change gears from the micro to the macro levels ..... but remains fully continuous ...'' [Latour et al , 2012].

Encompassing the Collective

The geometric basis of the universe as expressed by Edgar Allan Poe, asserts that the ‘universe.. is a sphere of which the centre is everywhere and circumference nowhere’ (Eureka, p 20) This is essentially a post-Euclidean conception of space, in line with the view of early 20th century physicist Alexander Friedmann who posits that the ‘universe is not finite in space, but neither does space have any boundary’ and so the centre of the universe is relative to every single atom — hence every single observer.

In many ways, the process of data collection and visualization that was carried out at the workshop tried at best to mimic this geometric basis of space. By starting with a single entity (say, mammals) the empiricist begins with nothing more than a named 'label'. One then extends the specification of this entity, by populating a list with an increasing number of elements. This process of 'learning' about an entity is essentially an infinite process, as many abstract associations maybe permitted to enter the list. However, the observer stops this iterative process at a point when he feels that he has enough knowledge to describe the entity within the (seemingly finite) 'scope' of study. What we then have is a highly individualized point of view with respect to one entity that has a view of all it's associated attributes.

It is worth noting here that the attributes themselves can be looked at as individualized entities, and vice versa, from their own view point, depending on the way in which one navigates, thereby making the map invertible. For instance while 'egg-laying' maybe one of the attributes of a 'mammal', if we navigated to define 'egg-laying' to be our starting entity, it's view point can contain attributes like 'mammals' and 'birds'. This process is entirely different from the bottom up approach of constructing a general view by combining individual counterparts. In fact, there is no one general view here, as the picture is an exploded graph emanating from a single entity's view point, each to it's own 'umwelt'.[Kaveli et al, 2010].

(Re)formation of Opinion

The formation of a fundamental percept in the human brain, for instance, during the cognitive activity of reading a text, is in itself a bottom-up serial process where individual words progressively make up semantic associations to form a meaningful structure (just as this sentence), along with contextual association with previously acquired knowledge. This capacity limit for information processing [Rene and Ivanoff, 2005] which is a prerequisite for our highly focussed mechanism of attention is the reason why we cannot capture the entire star map within a single glance at the night sky.

Somewhere down this iterative line of observing an entity, and not having access to all of its attributes in entirety, leads to over-specification and an entanglement with isolated systems, thereby falling into a local maxima as opposed to a global solution. This is the basis of opinion formation and by envisaging it as a 'closed' object it is transformed into a percept, open to interpretation and often conflicting with another, thereby resulting in a controversy.

One of the objectives of the controversy mapping workshop was to transform the 'immutable' percept surrounding a controversy into a visual map that all at once registers weblinked attributes surrounding it, to give us a possibly emergent and unbiased picture.

The Method to the Madness

The process of framing of a ‘controversial topic’ and the collation of massive data and links on the internet that surround the topic could indeed be a cumbersome task. An informed approach is thus required in order to achieve a meaningful result.

Firstly, one needs to consider reliable sources and means of knowledge production that provide enough fuel to kindle the analysis of the controversy. One needs to move on from casual matters of opinion or statements (such as “the cumulative effects of CFC result in ozone layer depletion”) to identifying a hypothesis or theory that is being actively contested by academicians and experts through research and publication. This serves to outline an important preliminary sketch of the controversy that exists within the community.

Secondly, it is essential to remember that specialized researchers do not exist in self-centered isolation but often operate in tandem with multiple stakeholders, investors, donors, sponsors and a diverse audience that they cater to through articles, books, research projects and published journals. For instance, several theorists who are into the business of developing a so-called ‘language of critique’ often ensure through working group meetings that a selected group of researchers are on the ‘same page’ while using common words to canvass a spearhead towards prospective calls from popular journals. At other times, one may perceive a very direct link between mainstream press and cutting-edge research. This group comprising allies and endorsers are an important constituent of the mapping process as they provide key points of entry into the controversy.

Further, as more and more data relating to a controversy is accrued, one must decipher not only how the position of the controversy is being dynamically shaped over time along with its stakeholders but also be able to extrapolate how and why its current position of uncertainty might evolve. This would involve identifying potential points of contention that could respark a debate over an issue that has reached near closure.

Mapping the Controversy around ‘Anthropocene’

|

|---|

The topic chosen by my group (which consisted of scholars Neesha Dutt, Muthatha Ramanathan and Prasanna Kolte) was ‘Anthropocene’, a geo-chronological term that was informally introduced by a Nobel laureate in the field of atmospheric chemistry, Paul Crutzen, at a dinner party. ‘Anthropocene’ apparently marks the post industrial period as a time window that represents the impact that human activities have had on earth’s ecological systems, thereby affecting climate change. The widespread acceptance and popularity of the the word has even seen a move to officially recognize ‘Anthropocene’ as geological unit of time, complemented by a number of dubious research projects that assume the ‘anthropocenic’ view of climate change. The tools used were Navicrawler to populate a massive list of webpages that featured the keyword and other landing websites that each of the webpages point to. The context of the websites based on their content were labelled manually and no native text parsing and analysis was used. An interconnected visual graph structure was then obtained using Gephi, a software that uses Force Layout -2 , a graph layout algorithm for network visualization. [M. Bastian et al, 2009].

Future Directions

Including a layer of geographical representation to the formation and spread of an opinion is a key direction towards which opinion mining and controversy mapping is headed. A limiting factor while crawling articles over the web using currently available digital tools is the inaccurate representation of geographical source. An article posted in a popular science blog in India, may actually have its server hosted in California and this fact may often be abstracted to our crawler.

Furthermore, apart from the geographical source of a web article, an interesting direction would be to employ geo-located public opinion interfaces to collect a sample set of public opinion related to an issue, across diverse geographical locations in realtime. This would serve as valuable layer to overlay onto the controversy web map.

Another constraint of the digital methods referred to here within, is the medium specific approach that does not look beyond the sample space of the internet. Listening to and analyzing internet social media dynamics and combing large data sets to churn out a report is not much of a challenge. Cross media influences in public and political opinion have become increasingly clear with television broadcasts and newspaper reports directly contributing to discussions that happen on internet forums and websites. Take for instance Blue Fin Labs that started off within the Cognitive Machines group of MIT Media Lab. Initially known as the Human Speechome project which used deep machine learning algorithms to map out relationships between spoken word and context, Blue Fin Labs now applies the same technique to map internet comments and posts to corresponding audio-visual stimuli in television broadcasts that caused those comments to be made on the web.

Video

Data visualization of connecting the social graph to the TV content graph

References

- Cappi, Alberto (1994). "Edgar Allan Poe's Physical Cosmology". The Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 35: 177–192

- Castells, M. (2000). Materials for an exploratory theory of the network society. British Journal of Sociology Vol. No. 51 Issue No. 1 (January/March 2000).

- Edgar Allen Poe (1848) ‘Eureka : A Prose Poem'.

- Kull, Kaveli 2010. Umwelt. In: Cobley, Paul (ed.), The Routledge Companion to Semiotics. London: Routledge, 348–349.

- Latour, B. et al 2012 “The Whole is Always Smaller Than It’s Parts A Digital Test of Gabriel Tarde’s Monads” British Journal of Sociology (forthcoming)http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/123-WHOLE-PART-FINAL.pdf

- M. Bastian, S. Heymann, and M. Jacomy, “Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks,” in International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence, 2009.

- M. E. J. Newman, “Analysis of weighted networks,” 2004, arxiv:cond-mat/0407503.

- Reynolds, C. W. (1987) Flocks, Herds, and Schools: A Distributed Behavioral Model, in Computer Graphics, 21(4) (SIGGRAPH '87 Conference Proceedings) pp. 25-34.

- Rene Marois and Jason Ivanoff, Capacity limits of information processing in the brain, TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences Vol.9 No.6 June 2005

- T. M. J. Fruchterman and E. M. Reingold, “Graph drawing by force-directed placement,” Softw: Pract. Exper., vol. 21 no. 11, pp. 1129–1164, Nov. 1991.

No Civil Society Members in the Cyber Regulations Advisory Committee

In multiple op-eds (Indian Express and Mint), I have pointed out the need for the government to reconstitute the "Cyber Regulations Advisory Committee" (CRAC) under section 88 of the Information Technology Act. That it be reconstituted along the model of the Brazilian Internet Steering Committee was also part of the suggestions that CIS sent to the government after a meeting FICCI had convened along with the government on September 4, 2012.

Section 88 requires that people "representing the interests principally affected" by Internet policy or "having special knowledge of the subject matter" be present in this advisory body. The main function of the CRAC is to advise the the Central Government "either generally as regards any rules or for any other purpose connected with this Act".

Despite this important function, the CRAC had — till November 2012 — only ever met twice, both times in 2001. The response to an RTI informed us that the body had never provided any advice to the government.

Government Not Serious

The increasing pressure on the government for botching up Internet regulations has led it to reconstitute the CRAC. However, the list of members of the committee shows that the government is not serious about this committee representing "the interests primarily affected" by Internet policy.

Importantly, this goes against the express wish of the Shri Kapil Sibal, the Union Minister for Communications and IT, who has repeatedly stated that he believes that Internet-related policymaking should be an inclusive process. Most recently, at the 2012 Internet Governance Forum he stated that we need systems that are:

"collaborative, consultative, inclusive and consensual, for dealing with all public policies involving the Internet"

Interestingly, despite the Hon'ble Minster verbally inviting civil society organizations (on November 23, 2012) for a meeting of the CRAC that happened on November 25, 2012, the Department of Electronics and Information Technology refused to send us invitations for the meeting. This hints at a disconnect between the political and bureaucratic wings of the government, at least at some levels.

Interestingly, this isn't the first time this has been pointed out. Na. Vijayashankar was levelling similar criticisms against the CRAC way back in August 2000 when the original CRAC was constituted.

Breakdown by Stakeholder Groupings

While there is no one universal division of stakeholders in Internet governance, but four goups are widely recognized: governments (national and intergovernmental), industry, technical community, and civil society. Using that division, we get:

- Government - 15 out of 22 members

- Industry bodies - 6 out of 22 members

- Technical community / Academia - 1 out of 22 members

- Civil society - 0 out of 22 members.

List of Members of Cyber Regulatory Advisory Committee

The official notification (G.S.R. 827(E)) is available on the DEIT website and came into force on November 16, 2012.

(Note: Names with strikethroughs have been removed from the CRAC since 2000, and those with emphasis have been added.)

- Minister, Ministry of Communication and Information Technology - Chairman

- Minister of State, Ministry of Communications and Information Technology - Member

- Secretary, Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, Department of Electronics and Information Technology - Member

- Secretary, Department of Telecommunications - Member

Finance Secretary - Member - Secretary, Legislative Department - Member

- Secretary, Department of Legal Affairs - Member

Shri T.K. Vishwanathan, Presently Member Secretary, Law Commission - Member - Secretary, Ministry of Commerce - Member

- Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs - Member

- Secretary, Ministry of Defence - Member

- Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India - Member

- Information Technology Secretary from the states by rotation - Member

- Director, IIT by rotation from the IITs - Member

- Director General of Police from the States by rotation - Member

- President, NASSCOM - Member

- President, Internet Service Provider Association - Member

- Director, Central Bureau of Investigation - Member

- Controller of Certifying Authority - Member

- Representative of CII - Member

- Representative of FICCI - Member

- Representative of ASSOCHAM - Member

- President, Computer Society of India - Member

- Group Coordinator, Department of Electronic and Information Technology - Member Secretary

7th India Digital Summit 2013

Agenda-2.pdf

—

PDF document,

963 kB (986588 bytes)

Agenda-2.pdf

—

PDF document,

963 kB (986588 bytes)

Draft International Principles on Communications Surveillance and Human Rights

The principles are still in draft form. The most recent version can be accessed here. This research was undertaken as part of the 'SAFEGUARDS' project that CIS is undertaking with Privacy International and IDRC.

Our goal is that these principles will provide civil society groups, industry, and governments with a framework against which we can evaluate whether current or proposed surveillance laws and practices are consistent with human rights. We are concerned that governments are failing to develop legal frameworks to adhere to international human rights and adequately protect communications privacy, particularly in light of innovations in surveillance laws and techniques.

These principles are the outcome of a consultation with experts from civil society groups and industry across the world. It began with a meeting in Brussels in October 2012 to address shared concerns relating to the global expansion of government access to communications. Since the Brussels meeting we have conducted further consultations with international experts in communications surveillance law, policy and technology.[1]

We are now launching a global consultation on these principles. Please send us comments and suggestions by January 3rd 2013, by emailing rights (at) eff (dot) org.

Preamble

Privacy is a fundamental human right, and is central to the maintenance of democratic societies. It is essential to human dignity and it reinforces other rights, such as freedom of expression and association, and is recognised under international human rights law.[2] Activities that infringe on the right to privacy, including the surveillance of personal communications by public authorities, can only be justified where they are necessary for a legitimate aim, strictly proportionate, and prescribed by law.[3]

Before public adoption of the Internet, well-established legal principles and logistical burdens inherent in monitoring communications generally limited access to personal communications by public authorities. In recent decades, those logistical barriers to mass surveillance have decreased significantly. The explosion of digital communications content and information about communications, or “communications metadata”, the falling cost of storing and mining large sets of data, and the commitment of personal content to third party service providers make surveillance possible at an unprecedented scale.[4]

While it is universally accepted that access to communications content must only occur in exceptional situations, the frequency with which public authorities are seeking access to information about an individual’s communications or use of electronic devices is rising dramatically—without adequate scrutiny. [5] When accessed and analysed, communications metadata may create a profile of an individual's private life, including medical conditions, political and religious viewpoints, interactions and interests, disclosing even greater detail than would be discernible from the content of a communication alone. [6] Despite this, legislative and policy instruments often afford communications metadata a lower level of protection and do not place sufficient restrictions on how they can be subsequently used by agencies, including how they are data-mined, shared, and retained.

It is therefore necessary that governments, international organisations, civil society and private service providers articulate principles establishing the minimum necessary level of protection for digital communications and communications metadata (collectively "information") to match the goals articulated in international instruments on human rights— including a democratic society governed by the rule of law. The purpose of these principles is to:

- Provide guidance for legislative changes and advancements related to communications and communications metadata to ensure that pervasive use of modern communications technology does not result in an erosion of privacy.

- Establish appropriate safeguards to regulate access by public authorities (government agencies, departments, intelligence services or law enforcement agencies) to communications and communications metadata about an individual’s use of an electronic service or communication media.

We call on governments to establish stronger protections as required by their constitutions and human rights obligations, or as they recognize that technological changes or other factors require increased protection.

These principles focus primarily on rights to be asserted against state surveillance activities. We note that governments are required not only to respect human rights in their own conduct, but to protect and promote the human rights of individuals in general.[7] Companies are required to follow data protection rules and yet are also compelled to respond to lawful requests. Like other initiatives,[8] we hope to provide some clarity by providing the below principles on how state surveillance laws must protect human rights.

The Principles

Legality: Any limitation to the right to privacy must be prescribed by law. Neither the Executive nor the Judiciary may adopt or implement a measure that interferes with the right to privacy without a previous act by the Legislature that results from a comprehensive and participatory process. Given the rate of technological change, laws enabling limitations on the right to privacy should be subject to periodic review by means of a participatory legislative or regulatory process

Legitimate Purpose: Laws should only allow access to communications or communications metadata by authorised public authorities for investigative purposes and in pursuit of a legitimate purpose, consistent with a free and democratic society.

Necessity: Laws allowing access to communications or communications metadata by authorised public authorities should limit such access to that which is strictly and demonstrably necessary, in the sense that an overwhelmingly positive justification exists, and justifiable in a democratic society in order for the authority to pursue its legitimate purposes, and which the authority would otherwise be unable to pursue. The onus of establishing this justification, in judicial as well as in legislative processes, is on the government.

Adequacy: Public authorities should restrain themselves from adopting or implementing any measure of intrusion allowing access to communications or communications metadata that is not appropriate for fulfillment of the legitimate purpose that justified establishing that measure.

Competent Authority: Authorities capable of making determinations relating to communications or communications metadata must be competent and must act with independence and have adequate resources in exercising the functions assigned to them.

Proportionality: Public authorities should only order the preservation and access to specifically identified, targeted communications or communications metadata on a case-by-case basis, under a specified legal basis. Competent authorities must ensure that all formal requirements are fulfilled and must determine the validity of each specific attempt to access or receive communications or communications metadata, and that each attempt is proportionate in relation to the specific purposes of the case at hand. Communications and communications metadata are inherently sensitive and their acquisition should be regarded as highly intrusive. As such, requests should at a minimum establish a) that there is a very high degree of probability that a serious crime has been or will be committed; b) and that evidence of such a crime would be found by accessing the communications or communications metadata sought; c) other less invasive investigative techniques have been exhausted; and d) that a plan to ensure that the information collected will be only that information reasonably related to the crime and that any excess information collected will be promptly destroyed or returned. Neither the scope of information types, the number or type of persons whose information is sought, the amount of data sought, the retention of that data held by the authorities, nor the level of secrecy afforded to the request should go beyond what is demonstrably necessary to achieve a specific investigation.

Due process: Due process requires that governments must respect and guarantee an individual’s human rights, that any interference with such rights must be authorised in law, and that the lawful procedure that governs how the government can interfere with those rights is properly enumerated and available to the general public.[9]While criminal investigations and other considerations of public security and safety may warrant limited access to information by public authorities, the granting of such access must be subject to guarantees of procedural fairness. Every request for access should be subject to prior authorisation by a competent authority, except when there is imminent risk of danger to human life. [10]

User notification: Notwithstanding the notification and transparency requirements that governments should bear, service providers should notify a user that a public authority has requested his or her communications or communications metadata with enough time and information about the request so that a user may challenge the request. In specific cases where the public authority wishes to delay the notification of the affected user or in an emergency situation where sufficient time may not be reasonable, the authority should be obliged to demonstrate that such notification would jeopardize the course of investigation to the competent judicial authority reviewing the request. In such cases, it is the responsibility of the public authority to notify the individual affected and the service provider as soon as the risk is lifted or after the conclusion of the investigation, whichever is sooner.

Transparency about use of government surveillance: The access capabilities of public authorities and the process for access should be prescribed by law and should be transparent to the public. The government and service providers should provide the maximum possible transparency about the access by public authorities without imperiling ongoing investigations, and with enough information so that individuals have sufficient knowledge to fully comprehend the scope and nature of the law, and when relevant, challenge it. Service providers must also publish the procedure they apply to deal with data requests from public authorities.

Oversight: An independent oversight mechanism should be established to ensure transparency of lawful access requests. This mechanism should have the authority to access information about public authorities' actions, including, where appropriate, access to secret or classified information, to assess whether public authorities are making legitimate use of their lawful capabilities, and to publish regular reports and data relevant to lawful access. This is in addition to any oversight already provided through another branch of government such as parliament or a judicial authority. This mechanism must provide – at a minimum – aggregate information on the number of requests, the number of requests that were rejected, and a specification of the number of requests per service provider and per type of crime. [11]

Integrity of communications and systems: It is the responsibility of service providers to transmit and store communications and communications metadata securely and to a degree that is minimally necessary for operation. It is essential that new communications technologies incorporate security and privacy in the design phases. In order, in part, to ensure the integrity of the service providers’ systems, and in recognition of the fact that compromising security for government purposes almost always compromises security more generally, governments shall not compel service providers to build surveillance or monitoring capability into their systems. Nor shall governments require that these systems be designed to collect or retain particular information purely for law enforcement or surveillance purposes. Moreover, a priori data retention or collection should never be required of service providers and orders for communications and communications metadata preservation must be decided on a case-by-case basis. Finally, present capabilities should be subject to audit by an independent public oversight body.

Safeguards for international cooperation: In response to changes in the flows of information and the technologies and services that are now used to communicate, governments may have to work across borders to fight crime. Mutual legal assistance treaties (MLATs) should ensure that, where the laws of more than one state could apply to communications and communications metadata, the higher/highest of the available standards should be applied to the data. Mutual legal assistance processes and how they are used should also be clearly documented and open to the public. The processes should distinguish between when law enforcement agencies can collaborate for purposes of intelligence as opposed to sharing actual evidence. Moreover, governments cannot use international cooperation as a means to surveil people in ways that would be unlawful under their own laws. States must verify that the data collected or supplied, and the mode of analysis under MLAT, is in fact limited to what is permitted. In the absence of an MLAT, service providers should not respond to requests of the government of a particular country requesting information of users if the requests do not include the same safeguards as providers would require from domestic authorities, and the safeguards do not match these principles.

Safeguards against illegitimate access: To protect individuals against unwarranted attempts to access communications and communications metadata, governments should ensure that those authorities and organisations who initiate, or are complicit in, unnecessary, disproportionate or extra-legal interception or access are subject to sufficient and significant dissuasive penalties, including protection and rewards for whistleblowers, and that individuals affected by such activities are able to access avenues for redress. Any information obtained in a manner that is inconsistent with these principles is inadmissible as evidence in any proceeding, as is any evidence derivative of such information.

Cost of surveillance: The financial cost of providing access to user data should be borne by the public authority undertaking the investigation. Financial constraints place an institutional check on the overuse of orders, but the payments should not exceed the service provider’s actual costs for reviewing and responding to orders, as such would provide a perverse financial incentive in opposition to user’s rights.

Signatories

Organisations

- Article 19 (International)

- Bits of Freedom (Netherlands)

- Center for Internet & Society India (CIS India)

- Derechos Digitales (Chile)

- Electronic Frontier Foundation (International)

- Privacy International (International)

- Samuelson-Glushko Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic (Canada)

- Statewatch (UK)

Individuals

- Renata Avila, human rights lawyer (Guatemala)

Footnotes

[1]For more information about the background to these principles and the process undertaken, see https://www.privacyinternational.org/blog/towards-international-principles-on-communications-surveillance

[2]Universal Declaration of Human Rights Article 12, United Nations Convention on Migrant Workers Article 14, UN Convention of the Protection of the Child Article 16, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Article 17; regional conventions including Article 10 of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, Article 11 of the American Convention on Human Rights, Article 4 of the African Union Principles on Freedom of Expression, Article 5 of the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, Article 21 of the Arab Charter on Human Rights, and Article 8 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms; Johannesburg Principles on National Security, Free Expression and Access to Information, Camden Principles on Freedom of Expression and Equality.

[3]Martin Scheinin, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism,” p11, available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/terrorism/rapporteur/docs/A_HRC_13_37_AEV.pdf. See also General Comments No. 27, Adopted by The Human Rights Committee Under Article 40, Paragraph 4, Of The International Covenant On Civil And Political Rights, CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.9, November 2, 1999, available at http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/0/6c76e1b8ee1710e380256824005a10a9?Opendocument.

[4]Communications metadata may include information about our identities (subscriber information, device information), interests, including medical conditions, political and religious viewpoints (websites visited, books and other materials read, watched or listened to, searches conducted, resources used), interactions (origins and destinations of communications, people interacted with, friends, family, acquaintances), location (places and times, proximities to others); in sum, logs of nearly every action in modern life, our mental states, interests, intentions, and our innermost thoughts.

[5]For example, in the United Kingdom alone, there are now approximately 500,000 requests for communications metadata every year, currently under a self-authorising regime for law enforcement agencies, who are able to authorise their own requests for access to information held by service providers. Meanwhile, data provided by Google’s Transparency reports shows that requests for user data from the U.S. alone rose from 8888 in 2010 to 12,271 in 2011.

[6]See as examples, a review of Sandy Petland’s work, ‘Reality Mining’, in MIT’s Technology Review, 2008, available at http://www2.technologyreview.com/article/409598/tr10-reality-mining/ and also see Alberto Escudero-Pascual and Gus Hosein, ‘Questioning lawful access to traffic data’, Communications of the ACM, Volume 47 Issue 3, March 2004, pages 77 - 82.

[7]Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, Frank La Rue, May 16 2011, available at http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/17session/a.hrc.17.27_en.pdf

[8]The Global Network Initiative establishes standards to help the ICT sector protect the privacy and free expression of their users. See http://www.globalnetworkinitiative.org/

[9]As defined by international and regional conventions mentioned above.

[10]Where judicial review is waived in such emergency cases, a warrant must be retroactively sought within 24 hours.

[11]One example of such a report is the US Wiretap report, published by the US Court service. Unfortunately this applies only to interception of communications, and not to access to communications metadata. See http://www.uscourts.gov/Statistics/WiretapReports/WiretapReport2011.aspx. The UK Interception of Communications Commissioner publishes a report that includes some aggregate data but it is does not provide sufficient data to scrutinise the types of requests, the extent of each access request, the purpose of the requests, and the scrutiny applied to them. See http://www.intelligencecommissioners.com/sections.asp?sectionID=2&type=top.

Statement of Solidarity on Freedom of Expression and Safety of Internet Users in Bangladesh

Bangladeshi blogger Asif Mohiuddin was brutally attacked in a stabbing last evening. His condition is currently said to be critical. Violent attacks on mediapersons have led to at least four deaths in the past year. This trend is now extending to those writing online.

It is the duty of societies at large to ensure that principles we universally consider sacrosanct, such as the right to life and liberty and of freedom of expression are in fact ideas, and of the government to actively protect the rights guaranteed under the Constitution of Bangladesh and to ensure they are not just words on paper.

Article 39 of the Constitution of Bangladesh—and Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—guarantee both the freedom of thought and conscience, as well as the right of every citizen of freedom of speech and expression, and freedom of the press.

Article 32 of the Constitution of Bangladesh—and Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—guarantee that no person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty except by law.

The attack on Asif Mohiuddin constitutes a violation these fundamental principle by criminals, and we request the government to act decisively to show it will not tolerate such violations.

Reporters Without Borders note that "the ability of those in the media to work freely has deteriorated alarmingly in Bangladesh, which is now ranked 129th of 179 countries in the 2011-2012 World Press Freedom Index".

In general, the situation of those working as non-professional 'citizen journalists' is even worse. In a 2010 report, the UN Special Rapporteur wrote: