Blog

Interview with Mr. Billy Hawkes - Irish Data Protection Commissioner

This research was undertaken as part of the 'SAFEGUARDS' project that CIS is undertaking with Privacy International and IDRC

The Irish Data Protection Commissioner was asked the following questions:

1. What powers does the Irish Data Commissioner´s office have? In your opinion, are these sufficient? Which powers have been most useful? If there is a lack, what would you feel is needed?

2. Does your office differ from other EU data protection commissioner offices?

3. What challenges has your office faced? What is the most common type of privacy violation that your office has faced?

4. Why should privacy legislation be enacted in India?

5. Does India need a Privacy Commissioner? Why? If India creates a Privacy Commissioner, what structure / framework would you suggest for the office?

6. How do you think data should be regulated in India? Do you support the idea of co-regulation or self-regulation?

7. How can India protect its citizens´ data when it is stored in foreign servers?

video

Interview with the Citizen Lab on Internet Filtering in India

A few days ago, Masashi Crete-Nishihata (research manager) and Jakub Dalek (systems administrator) from the Citizen Lab visited the Centre for Internet and Society (CIS) to share their research with us.

The Citizen Lab is an interdisciplinary laboratory based at the Munk School of Global Affairs at the University of Toronto, Canada. The OpenNet Initiative is one of the Citizen Lab's ongoing projects which aims to document patterns of Internet surveillance and censorship around the world. OpenNet.Asia is another ongoing project which focuses on censorship and surveillance in Asia.

The following video entails an interview of both Masashi Crete-Nishihata and Jakub Dalek on the following questions:

1. Why is it important to investigate Internet filtering around the world?

2. How high are the levels of Internet filtering in India, in comparison to the rest of the world?

3. "Censorship and surveillance of the Internet aim at tackling crime and terrorism and in increasing overall security." Please comment.

4. What is Netsweeper and how is it being used in India? What consequences does this have?

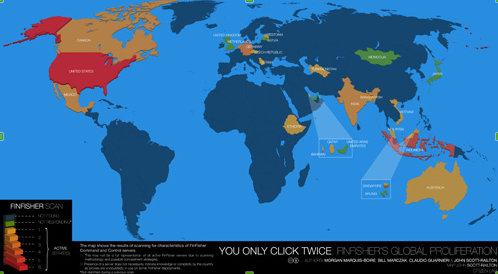

5. What is FinFisher and how could it be used in India?

Video

Report on the 4th Privacy Round Table meeting

This research was undertaken as part of the 'SAFEGUARDS' project that CIS is undertaking with Privacy International and IDRC

In furtherance of Internet Governance multi-stakeholder Initiatives and Dialogue in 2013, the Centre for Internet and Society (CIS) in collaboration with the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), and the Data Security Council of India (DSCI), is holding a series of six multi-stakeholder round table meetings on “privacy” from April 2013 to August 2013. The CIS is undertaking this initiative as part of their work with Privacy International UK on the SAFEGUARD project.

In 2012, the CIS and DSCI were members of the Justice AP Shah Committee which created the “Report of Groups of Experts on Privacy”. The CIS has recently drafted a Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013, with the objective of contributing to privacy legislation in India. The CIS has also volunteered to champion the session/workshops on “privacy” in the meeting on Internet Governance proposed for October 2013.

At the roundtables the Report of the Group of Experts on Privacy, DSCI´s paper on “Strengthening Privacy Protection through Co-regulation” and the text of the Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013 will be discussed. The discussions and recommendations from the six round table meetings will be presented at the Internet Governance meeting in October 2013.

The dates of the six Privacy Round Table meetings are enlisted below:

-

New Delhi Roundtable: 13 April 2013

-

Bangalore Roundtable: 20 April 2013

-

Chennai Roundtable: 18 May 2013

-

Mumbai Roundtable: 15 June 2013

-

Kolkata Roundtable: 13 July 2013

-

New Delhi Final Roundtable and National Meeting: 17 August 2013

Following the first three Privacy Round Tables in Delhi, Bangalore and Chennai, this report entails an overview of the discussions and recommendations of the fourth Privacy Round Table meeting in Mumbai, on 15th June 2013.

Discussion of the Draft Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013

Discussion of definitions: Chapter 1

The fourth Privacy Round Table meeting began with a discussion of the definitions in Chapter 1 of the draft Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013. In particular, it was stated that in India, the courts argue that the right to privacy indirectly derives from the right to liberty, which is guaranteed in article 21 of the constitution. However, this provision is inadequate to safeguard citizens from potential abuse, as it does not protect their data adequately. Thus, all the participants in the meeting agreed with the initial notion that India needs privacy legislation which will explicitly regulate data protection, the interception of communications and surveillance within India. To this extent, the participants started a thorough discussion of the definitions used in the draft Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013.

It was specified in the beginning of the meeting that the definition of personal data in the Bill applies to natural persons and not to juristic persons. A participant argued that the Information Technology Act refers to personal data and that the draft Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013 should be harmonised with existing rules. This was countered by a participant who argued that the European Union considers the Information Technology Act inadequate in protecting personal data in India and that since India does not have data secure adequacy, the Bill and the IT Act should not be harmonised.

Other participants argued that all other relevant acts should be quoted in the discussion so that it does not overlap with existing provisions in other rules, such as the IT Act. Furthermore, this was supported by the notion that the Bill should not clash with existing legislation, but this was dismissed by the argument that this Bill – if enacted into law – would over right all other competing legislation. Special laws over right general laws in India, but this would be a special law for the specific purpose of data protection.

The definition of sensitive personal data includes biometric data, political affiliation and past criminal history, but does not include ethnicity, caste, religion, financial information and other such information. It was argued that one of the reasons why such categories are excluded from the definition of sensitive personal data is because the government requests such data on a daily basis and that it is not willing to take any additional expense to protect such data. It was stated that the Indian government has argued that such data collection is necessary for caste census and that financial information, such as credit data, should not be included in the definition for sensitive personal data, because a credit Act in India specifically deals with how credit data should be used, shared and stored.

Such arguments were backlashed by participants arguing that definitions are crucial because they are the “building blocks” of the entire Bill and that ethnicity, caste, religion and financial information should not be excluded from the Bill, as they include information which is sensitive within the Indian context. In particular, some participants argued that the Bill would be highly questioned by countries with strong privacy legislation, as certain categories of information, such as ethnicity and caste, are definitely considered to be sensitive personal information within India. The argument that it is too much of a bureaucratic and financial burden for the Indian government to protect such personal data was countered by participants who argued that in that case, the government should not be collecting that information to begin with – if it cannot provide adequate safeguards.

The debate on whether ethnicity, religion, caste and financial information should be included in the definition for sensitive personal data continued with a participant arguing that no cases of discrimination based on such data have been reported and that thus, it is not essential for such information to be included in the definition. This argument was strongly countered by participants who argued that the mere fact that the government is interested in this type of information implies that it is sensitive and that the reasons behind the governments´ interest in this information should be investigated. Furthermore, some participants argued that a new provision for data on ethnicity, religion, caste and financial information should be included, as well as that there is a difference between voluntarily handing over such information and being forced to hand it over.

The inclusion of passwords and encryption keys in the definition of sensitive personal data was highly emphasized by several participants, especially since their disclosure can potentially lead to unauthorised access to volumes of personal data. It was argued that private keys in encryption are extremely sensitive personal data and should definitely be included within the Bill.

In light of the NSA leaks on PRISM, several participants raised the issue of Indian authorities protecting data stored in foreign servers. In particular, some participants argued that the Bill should include provisions for data stored in foreign servers in order to avoid breaches for international third parties. However, a participant argued that although Indian companies are subject to the law, foreign data processors cannot be subject to Indian law, which is why they should instead provide guarantees through contracts.

Several participants strongly argued that the IT industry should not be subject to some of the privacy principles included in the Report of the Group of Experts on Privacy, such as the principle of notice. In particular, they argued that customers choose to use specific services and that by doing so, they trust companies with their data; thus the IT industry should not have to comply with the principle of notice and should not have to inform individuals of how they handle their data.

On the issue of voluntary disclosure of personal data, a participant argued that, apart from the NPR and UID, Android and Google are conducting the largest data collection within India and that citizens should have the jurisdiction to go to court and to seek that data. The issue of data collection was further discussed over the next sessions.

Right to Privacy: Chapter 2

The discussion of the right to privacy, as entailed in chapter 2 of the draft Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013, started with a participant stating that governments own the data citizens hand over to them and that this issue, along with freedom from surveillance and illegal interception, should be included in the Bill.

Following the distinction between exemptions and exceptions to the right to privacy, a participant argued that although it is clear that the right to privacy applies to all natural persons in India, it is unclear if it also applies to organizations. This argument was clarified by a participant who argued that chapter 2 clearly protects natural persons, while preventing organisations from intervening to this right. Other participants argued that the language used in the Bill should be more gender neutral and that the term “residential property” should be broadened within the exemptions to the right to privacy, to also include other physical spaces, such as shops. On this note, a participant argued that the word “family” within the exemptions should be more specifically defined, especially since in many cases husbands have controlled their wives when they have had access to their personal accounts.

The definition of “natural person” was discussed, while a participant raised the question of whether data protection applies to persons who have undergone surgery and who have changed their sexual orientation; it was recommended that such provisions are included within the Bill. The above questions were answered by a participant who argued that the generic European definitions for “natural persons” and “family” could be adopted, as well as that CCTV cameras used in public places, such as shops, should be subject to the law, because they are used to monitor third parties.

Other participants suggested that commercial violations are not excluded from the Bill, as the broadcasting of people, for example, can potentially lead to a violation of the right to privacy. In particular, it was argued that commercial establishments should not be included in the exemptions section of the right to privacy, in contrast to other arguments that were in favour of it. Furthermore, participants argued that the interaction between transparency and freedom of information should be carefully examined and that the exemptions to the right to privacy should be drafted accordingly.

Protection of Personal Data: Chapter 3

Some of the most important discussions in the fourth Privacy Round Table meeting revolved around the protection of personal data.

Collection of personal data

The discussion on the collection of personal data started with a statement that the issue of individual consent prior to data collection is essential and that in every case, the data subject should be informed of its data collection, data processing, data sharing and data retention.

It was pointed out that, unlike most privacy laws around the world, this Bill is affirmative because it states that data can only be collected once the data subject has provided prior consent. It was argued that if this Bill was enacted into law, it would probably be one of the strictest laws in the world in terms of data collection, because data can only be collected with individual consent and a legitimate purpose. Data collection in the EU is not as strict, as there are some exemptions to individual consent; for example, if someone in the EU has a heart attack, other individuals can disclose his or her information. It was emphasized that as this Bill limits data collection to individual consent, it does not serve other cases when data collection may be necessary but individual consent is not possible. A participant pointed out that, although the Justice AP Shah Report of the Group of Experts on Privacy states that “consent may not be acquired in some cases”, such cases are not specified within the Bill.

Other issues that were raised are that the Bill does not specify how individual consent would be obtained as a prerequisite to data collection. In particular, it remains unclear whether such consent would be acquired through documentation, a witness or any other way. Thus it was emphasized that the method for acquiring individual consent should be clearly specified within the Bill, especially since it is practically hard to obtain consent for large portions of the Indian population that live below the line of poverty.

A participant argued that data collection on private detectives, from reality TV shows and on physical movement and location should also be addressed in the Bill. Furthermore, other participants argued that specific explanations to exempt medical cases and state collection of data which is directly related to the provision of welfare should be included in the Bill. Participants recommended that individuals should have the right to opt out from data collection for the purpose of providing welfare programmes and other state-run programmes.

The need to define the term “legitimate purpose” was pointed out to ensure that data is not breached when it is being collected. A participant recommended the introduction of a provision in the Bill for anonymising data in medical case studies and it was pointed out that it is very important to define what type of data can be collected. In particular, it was argued that a large range of personal data is being collected in the name of “public health” and “public security” and that, in many cases, patients may provide misinformed consent, because they may think that the revelation of their personal data is necessary, when actually it might not be. It was recommended that this issue is addressed and that necessary provisions are included in the Bill.

In the cases where data is collected for statistics, individuals may not be informed of their data being collected and may not provide consent. It was also recommended that this issue is addressed and included in the Bill. However, it was also pointed out that in many cases, individuals may choose to use a service, but they may not be able to consent to their data collection and Android is an example of this. Thus it was argued that companies should be transparent about how they handle users´ data and that they should require individuals´ consent prior to data collection.

It was emphasized that governments have a duty of transparency towards their citizens and that the fact that, in many cases, citizens are obliged to hand over their data without giving prior consent to how their data is being used should be taken into consideration. In particular, it was argued that many citizens need to use specific services or welfare programmes and that they are obliged to hand over their personal information. It was recommended that the Bill incorporates provisions which would oblige all services to acquire individual consent prior to data collection. However, the issue that was raised is that often companies provide long and complicated contracts and policy guides which discourage individuals from reading them and thus from providing informed consent; it was recommended that this issue is addressed as well.

Storage and destruction of personal data

The discussion on the storage and destruction of personal data started with a statement that different sectors should have different data retention frameworks. The proposal that a ubiquitous data retention framework should not apply to all sectors was challenged by a participant who stated that the same data retention period should apply to all ISPs and telecoms. Furthermore, it was added that regulators should specify the data retention period based on specific conditions and circumstances. This argument was countered by participants who argued that each sector should define its data retention framework depending on many variables and factors which affect the collection and use of data.

In European laws, no specific data retention periods are established. In particular, European laws generally state that data should only be retained for a period related to the purpose of its collection. Hence it was pointed out that data retention frameworks should vary from sector to sector, as data, for example, may need to be retained longer for medical cases than for other cases. This argument, however, was countered by participants who argued that leaving the prescription of a data retention period to various sectors may not be effective in India.

Questions of how data retention periods are defined were raised, as well as which parties should be authorised to define the various purposes for data retention. One participant recommended that a common central authority is established, which can help define the purpose for data retention and the data retention period for each sector, as well as to ensure that data is destroyed once the data retention period is over. Another participant recommended that a three year data retention period should be applied to all sectors by default and that such periods could be subject to change depending on specific cases.

Security of personal data and duty of confidentiality

Participants recommended that the definition of “data integrity” should be included in Chapter 1 of the draft Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013. Other participants raised the need to define the term “adequacy” in the Bill, as well as to state some parameters for it. It was also suggested that the term “adequacy” could be replaced by the term “reasonable”.

One of the participants raised the issue of storing data in a particular format, then having to transfer that data to another format which could result in the modification of that data. It was pointed out that the form and manner of securing personal data should be specifically defined within the Bill. However, it was argued that the main problem in India is the implementation of the law, and that it would be very difficult to practically implement the draft Privacy (Protection) Bill in India.

Disclosure of personal data

The discussion on the disclosure of personal data started with a participant arguing that the level of detail disclosed within data should be specified within the Bill. Another participant argued that the privacy policies of most Internet services are very generic and that the Bill should prevent such services from publicly disclosing individuals´ data. On this note, a participant recommended that a contract and a subcontract on the disclosure of personal data should be leased in order to ensure that individuals are aware of what they are providing their consent to.

It was recommended that the Bill should explicitly state that data should not be disclosed for any other purpose other than the one for which an individual has provided consent. Data should only be used for its original purpose and if the purpose for accessing data changes within the process, consent from the individual should be acquired prior to the sharing and disclosure of that data. A participant argued that banks are involved with consulting and other advisory services which may also lead to the disclosure of data; all such cases when information is shared and disclosed to (unauthorised) third parties should be addressed in the Bill.

Several participants argued that companies should be responsible for the data they collect and that should not share it or disclose it to unauthorised third parties without individuals´ knowledge or consent. On this note, other participants argued that companies should be legally allowed to share data within a group of companies, as long as that data is not publicly disclosed. An issue that was raised by one of the participants is that online companies, such as Gmail, usually acquire consent from customers through one “click” to a huge document which not only is usually not read by customers, but which vaguely entails all the cases for which individuals would be providing consent for. This creates the potential for abuse, as many specific cases which would require separate, explicit consent, are not included within this consent mechanism.

This argument was countered by a participant who stated that the focus should be on code operations for which individuals sign and provide consent, rather than on the law, because that would have negative implications on business. It was highlighted that individuals choose to use specific services and that by doing so they trust companies with their data. Furthermore, it was argued that the various security assurances and privacy policies provided by companies should suffice and that the legal regulation of data disclosure should be avoided.

Consent-based sharing of data should be taken into consideration, according to certain participants. The factor of “opt in” should also be included when a customer is asked to give informed consent. Participants also recommended that individuals should have the power to “opt out”, which is currently not regulated but deemed to be extremely important. Generally it was argued that the power to “opt in” is a prerequisite to “opt out”, but both are necessary and should be regulated in the Bill.

A participant emphasized the need to regulate phishing in the Bill and to ensure that provisions are in place which could protect individuals´ data from phishing attacks. On the issue of consent when disclosing personal data, participants argued that consent should be required even for a second flow of data and for all other flows of data to follow. In other words, it was recommended that individual consent is acquired every time data is shared and disclosed. Moreover, it was argued that if companies decide to share data, to store it somewhere else or to disclose it to third parties years after its initial collection, the individual should have the right to be informed.

However, such arguments were countered by participants who argued that systems, such as banks, are very complex and that they don´t always have a clear idea of where data flows. Thus, it was argued that in many cases, companies are not in a position to control the flow of data due to a lack of its lack of traceability and hence to inform individuals every time their data is being shared or disclosed.

Participants argued that the phrase “threat to national security” in section 10 of the Bill should be explicitly defined, because national security is a very broad term and its loose interpretation could potentially lead to data breaches. Furthermore, participants argued that it is highly essential to specify which authorities would determine if something is a threat to national security.

The discussion on the disclosure of personal data concluded with a participant arguing that section 10 of the Bill on the non-disclosure of information clashes with the Right to Information Act (RTI Act), which mandates the opposite. It was recommended that the Bill addresses the inevitable clash between the non-disclosure of information and the right to information and that necessary provisions are incorporated in the Bill.

Presentation by Mr. Billy Hawkes – Irish Data Protection Commissioner

The Irish Data Protection Commissioner, Mr. Billy Hawkes, attended the fourth Privacy Round Table meeting in Mumbai and discussed the draft Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013.

In particular, Mr. Hawkes stated that data protection law in Ireland was originally introduced for commercial purposes and that since 2009 privacy has been a fundamental right in the European Union which spells out the basic principles for data protection. Mr. Hawkes argued that India has successful outsourcing businesses, but that there is a concern that data is not properly protected. India has not been given data protection adequacy by the European Union, mainly because the country lacks privacy legislation.

There is a civic society desire for better respect for human rights and there is the industrial desire to be considered adequate by the European Union and to attract more international customers. However, privacy and data protection are not covered adequately in the Information Technology Act, which is why Mr. Hawkes argued that the draft Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013 should be enacted in compliance with the principles from the Justice AP Shah Report on the Group of Experts on Privacy. Enacting privacy legislation in India would, according to Mr. Hawkes, be a prerequisite so that India can potentially be adequate in data protection in the future.

The Irish Data Protection Commissioner referred to the current negotiations taking place in the European Union for the strengthening of the 1995 Directive on Data Protection, which is currently being revisited and which will be implemented across the European Union. Mr. Hawkes emphasized that it is important to have strong enforcement powers and to ask companies to protect data. In particular, he argued that data protection is good customer service and that companies should acknowledge this, especially since data protection reflects respect towards customers.

Mr. Hawkes highlighted that other common law countries, such as Canada and New Zealand, have achieved data secure adequacy and that India can potentially be adequate too. More and more countries in the world are seeking European adequacy. Privacy law in India would not only safeguard human rights, but it´s also good business and would attract more international customers, which is why European adequacy is important. In every outsourcing there needs to be a contract which states that the requirements of the data controller have been met. Mr. Hawkes emphasized that it is a competitive disadvantage in the market to not be data adequate, because most countries will not want their data outsourced to countries which are inadequate in data security.

As a comment to previous arguments stated in the meeting, it was pointed out that in Ireland, if companies and banks are not able to track the flow of data, then they are considered to be behaving irresponsibly. Furthermore, Mr. Hawkes states that data adequacy is a major reputational issue and that inadequacy in data security is bad business. It is necessary to know where the responsibility for data lies, which party initially outsourced the data and how it is currently being used. Data protection is a fundamental right in the European Union and when data flows outside the European Union, the same level of protection should apply. Thus other non-EU countries should comply with regulations for data protection, not only because it is a fundamental human right, but also because it is bad business not to do so.

The Irish Data Protection Commissioner also referred to the “Right to be Forgotten”, which is the right to be told how long data will be retained for and when it will be destroyed. This provides individuals some control over their data and the right to demand this control.

On the funding of data protection authorities, Mr. Hawkes stated that funding varies and that in most cases, the state funds the data protection authority – including Ireland. Data protection authorities are substantially funded by their states across the European Union and they are allocated a budget every year which is supposed to cover all their costs. The Spanish data protection authorities, however, are an exception because a large amount of their activities are funded by fines.The data protection authorities in the UK (ICO) are funded through registration fees paid by companies and other organizations.

When asked about how many employees are working in the Irish data protection commissioner´s office, Mr. Hawkes replied that only thirty individuals are employed. Employees working in the commissioner´s office are responsible for overseeing the protection of the data of Facebook users, for example. Facebook-Ireland is responsible for handling users´ data outside of North America and the commissioner´s office conducted a detailed analysis to ensure that data is protected and that the company meets certain standards. Facebook´s responsibility is limited as a data controller as individuals using the service are normally covered by the so-called "household exemption" which puts them outside the scope of data protection law. The data protection commissioner conducts checks and balances, writes reports and informs companies that if they comply with privacy and data protection, then they will be supported.

Data protection in Ireland covers all the organizations, without exception. Mr. Hawkes stated that EU data protection commissioners meeting in the "Article 29" Working Party spend a significant amount of their time dealing with companies like Google and Facebook and with whether they protect their customers´ data.

The Irish Data Protection Commissioner recommended that India establishes a data protection commission based on the principles included in the Justice AP Shah Report of the Group of Experts on Privacy. In particular, an Indian data protection commission would have to deal with a mix of audit inspections, complaints, greater involvement with sectors, transparency, accountability and liability to the law. Mr. Hawkes emphasized that codes of practice should be implemented and that the focus should not be on bureaucracy, but on accountability. It was recommended that India should adopt an accountability approach, where punishment will be in place when data is breached.

On the recent leaks on the NSA´s surveillance programme, PRISM, Mr. Hawkes commented that he was not surprised. U.S. companies are required to give access to U.S. law enforcement agencies and such access is potentially much looser in the European Union than in the U.S., because in the U.S. a court order is normally required to access data, whereas in the European Union that is not always the case. Mr. Hawkes stated that there needs to be a constant questioning of the proportionality, necessity and utility of surveillance schemes and projects in order to ensure that the right to privacy and other human rights are not violated.

Mr. Hawkes stated that the same privacy law should apply to all organizations and that India should ensure its data adequacy over the next years. The Irish Data Protection Commissioner is responsible for Facebook Ireland and European law is about protecting the rights of any organisation that comes under European jurisdiction, whether it is a bank or a company. Mr. Billy Hawkes emphasized that the focus in India should be on adequacy in data security and in protecting citizens´ rights.

Meeting conclusion

The fourth Privacy Round Table meeting entailed a discussion of the draft Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013 and Mr. Billy Hawkes, the Irish Data Protection Commissioner, gave a presentation on adequacy in data security and on his thoughts on data protection in India. The discussion on the draft Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013 led to a debate and analysis of the definitions used in the Bill, of chapter 2 on the right to privacy, and on data collection, data retention, data sharing and data disclosure. The participants provided a wide range of recommendations for the improvement of the draft Privacy (Protection) Bill and all will be incorporated in the final draft. The Irish Data Protection Commissioner, Mr. Billy Hawkes, stated that the European Union has not given data adequacy to India because it lacks privacy legislation and that data inadequacy is not only a competitive disadvantage in the market, but it also shows a lack of respect towards customers. Mr. Hawkes strongly recommended that privacy legislation in compliance with the Justice AP Shah report is enacted, to ensure that India is potentially adequate in data security in the future and that citizens´ right to privacy and other human rights are guaranteed.

Open Letter to Prevent the Installation of RFID tags in Vehicles

This research was undertaken as part of the 'SAFEGUARDS' project that CIS is undertaking with Privacy International and IDRC

This letter is with regards to the installation of Radio Frequency Identification Tags (RFID) in vehicles in India.

On behalf of the Centre for Internet and Society, we urge you to prevent the installation of RFID tags in vehicles in India, as the legality, necessity and utility of RFID tags have not been adequately proven. Such technologies raise major ethical concerns, since India lacks privacy legislation which could safeguard individuals' data.

The proposed rule 138A of the Central Motor Vehicle Rules, 1989, mandates that RFID tags are installed in all light motor vehicles in India. However, section 110 of the Motor Vehicles Act (MV Act), 1988, does not bestow on the Central Government a specific empowerment to create rules in respect to RFID tags. Thus, the legality of the proposed rule 138A is questioned, and we urge you to not proceed with an illegal installation of RFID tags in vehicles until the Supreme Court has clarified this issue.

The installation of RFID tags in vehicles is not only currently illegal, but it also raises majors privacy concerns. RFID tags yield locational information, and thus reveal information as to an individual’s whereabouts. This could lead to a serious invasion of the right to privacy, which is at the core of personal liberty, and constitutionally protected in India. Moreover, the installation of RFID tags in vehicles is not in compliance with the privacy principles of the Report of the Group of Experts on Privacy, as, among other things, the architecture of RFID tags does not allow for consent to be taken from individuals for the collection, use, disclosure, and storage of information generated by the technology.[1]

The Centre for Internet and Society recently drafted the Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013 – a citizen's version of a possible privacy legislation for India.[2] The Bill defines and establishes the right to privacy and regulates the interception of communications and surveillance, and would include the regulation of technologies like RFID tags. As this Bill has not been enacted into law and India lacks a privacy legislation which could safeguard individuals' data, we strongly urge you to not require the mandatory installation of RFID tags in vehicles, as this could potentially violate individuals' right to privacy and other human rights.

As the proposed rule 138A, which mandates the installation of RFID tags in vehicles, is currently illegal and India lacks privacy legislation which would regulate the collection, use, sharing of, disclosure and retention of data, we strongly urge you to ensure that RFID tags are not installed in vehicles in India and to play a decisive role in protecting individuals' right to privacy and other human rights.

Thank you for your time and for considering our request.

Sincerely,

Centre for Internet and Society (CIS)

[1]. Report of the Group of Experts on Privacy: http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/rep_privacy.pdf

[2].Draft Privacy (Protection) Bill 2013: http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/privacy-protection-bill-2013.pdf

The State is Snooping: Can You Escape?

The Snowden Leaks have made it amply clear that the covert surveillance conducted by governments is no longer covert. Information by its very nature is prone to leaks. The discretion lies completely in the hands of the personnel handling your data or information. Whether it is through knowledge obtained by an intelligence analyst about the US Government conducting indiscriminate surveillance, or hackers infiltrating a secure system and leaking personal information, stored information has a tendency to come out in the open sooner or later.

This raises the question whether, with the advancement of technologies, we should trust our personal information and data with computers. Should we have more stringent laws and procedural safeguards to protect our personal information? Of course, the broader question that remains is whether we have a ‘Right to be Forgotten’.

Similar to PRISM in the US, India is also implementing a Centralized Monitoring System (CMS) which would have the capabilities to conduct multiple privacy-intrusive activities, ranging from call data record analysis to location based monitoring. Given the circumstances and the current revelations by a whistleblower in the US, it is more than imperative to take a closer look at the surveillance technologies which are being deployed by India and question what implications it might have in the future.

Technological shift and procedural safeguards

The need for procedural safeguards was brought to light in the Supreme Court case, when news reports surfaced about the tapping of politicians' phones by the CBI. The Court while deciding on the issue of phone tapping in the case of People’s Union of Civil Liberties v. Union of India (1996), observed that the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885 is an ancient legislation and does not address the issue of telephone tapping. Thereafter, the court issued guidelines, which were implemented by the Government by amending and inserting Rule 419A of the Indian Telegraph Rules, 1951. These procedural safeguards ensure that due process will be followed by any law enforcement agency, while conducting surveillance.

Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885 grants the power to the Government to conduct surveillance provided that there is an occurrence of any public emergency or public safety. If and only if the conditions of public safety and public emergency are compromised, and if the concerned authority is convinced that it is expedient to issue such an order for interception in the interest of “the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States or public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of an offence” is surveillance legitimized. The same was reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in the 1996 judgment on wire tapping.

Now, as the Government of India is planning to launch a new technology, the Centralized Monitoring System (CMS) which would snoop, track and monitor communication data flowing through telecom and data networks, the question arises: can we have procedural safeguards which would protect our right to privacy against technologies such as the CMS?

The key component of a procedural safeguard is human discretion; either a court authorization or an order from a high ranking government official is necessary to conduct targeted surveillance and the reasons for conducting surveillance have to be recorded in writing. This is the procedure which is ordinarily followed by law enforcement agencies before conducting any form of surveillance. However, with the computational turn, governments have resorted to practices which would do away with the human discretion. Dragnet surveillance allows for blanket surveillance. Before getting to the problems in evolving a due process for systems like CMS, it is imperative to examine the capabilities of the system.

Centralized Monitoring System and death of due process

Setting up of a CMS was conceptualized in India after the 2008 Mumbai attacks. It was further consolidated and found a place in the Report of the Telecom Working Group on the Telecom Sector for the Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012-2017). The Report was published in August, 2011 and goes into the details of the CMS.

When machines and robots are deployed to conduct blanket surveillance and impinge on the most fundamental right to life and liberty, and also violate the basic tenets of due process, then much cannot be done by way of procedures. What then do we resort to, is the primary question. Can there be a compromise between the right to privacy and security?

The Report indicates that the technology will cater to “the requirements of security management for law enforcement agencies for interception, monitoring, data analysis/mining, antiâ€socialâ€networking using the country’s telecom infrastructure for unlawful activities.”

The CMS will also be capable of running algorithms for interception of connection oriented networks, algorithms for interception of voice over internet protocol (VoIP), video over IP and GPS based monitoring systems. These algorithms would be able to intercept any communication without any intervention from the telecom or internet service provider. It would also have the capability to intercept and analyze data on any communication network as well as to conduct location based monitoring by tracking GPS locations. Given such capabilities, it is clear that a computer system will be sifting through the internet/communication data and will conduct surveillance as instructed through algorithms. This would include identifying patterns, profiling and also storing data for posterity. Moreover, the CMS will have direct access to the telecommunication infrastructure and would be monitoring all forms of communication.

With the introduction of CMS, state surveillance will shift to blanket surveillance from the current practice of targeted surveillance which can be carried out under specific circumstances that are well defined in the law and in judgments. Moreover, when it comes to current means of surveillance, there are well-defined procedures under the law which have the ability to prevent misuse of the surveillance systems. This is not to say that the current procedural safeguards under the laws are not prone to abuse, but if implemented properly, there is less chance of them being misused. Furthermore, with strong privacy and data protection laws, unlawful and illegal surveillance can be minimized.

In the current legal framework, with respect to surveillance, if CMS is implemented then it will be in violation of the fundamental right to privacy and freedom of speech as guaranteed under our Constitution. It will be also in contravention of the procedural safeguards laid down in the Supreme Court judgement and the Rule 419A of Indian Telegraph Rules, thereof. Strong privacy laws and data protection laws may be put in place, which are completely absent now. But at the end of the day, a machine will be spying on every citizen of India or anyone using any communication services, without any specific targets or suspects.

In the People’s Union of Civil Liberties v. Union of India (1996), the Supreme Court laid down that “the substantive law as laid down in Section 5(2) of the [Indian Telegraph Act, 1885] must have procedural backing so that the exercise of power is fair and reasonable.” But with technologies such as CMS, it will be very difficult to have any form of procedural backing because the system would do away with human discretion which happens to be a key ingredient of any legal procedure.

The argument which can be made in favour of CMS, if any, is that a machine will be going through personal data and it will not be available to any personnel or law enforcement agency without authorization and therefore, it will adhere to the due process. However, such a system will be keeping track of all personal information. Right to privacy is the right to be left alone and any incursion on this fundamental right can only be allowed in special cases, in cases of public emergency or threat of public safety. So, electronic blanket surveillance without human intervention also amounts to violation of the substantive law, which specifically allows surveillance only to be conducted under certain conditions, and not through a system such as CMS that is designed to keep a constant watch on everyone, irrespective of the fact whether there is a need to do so.

Additionally, there exists a strong, pre-established notion that whatever comes out of a computer is bound to be true and authentic and there cannot be any mistakes. We have witnessed this in the past where an IT professional from Bangalore was arrested and detained by the Maharashtra Police for posting derogatory content on Orkut about Shivaji. Later, it was found that the records acquired from the Internet Service Provider were incorrect and the individual had been arrested and detained illegally.

Telephone bills, credit card bills coming out from a computer system are often held to be authentic and error-free. With UID, our identity has been reduced to a number and biometrics stored in a database corresponding to that number. It is this trust in anything which comes out of a computer or a machine that can lead to massive abuse of the system in the absence of any form of checks and balance in place. Artificial things taking control over human lives and our almost unflinching trust in technology will not only cause gross violations of privacy but will also be the death of due process and basic human rights as we know it.

In this regard, due emphasis should be given to the landmark Supreme Court judgment in the case of Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978) which deals with issues related to due process and privacy. It states that "procedure which deals with the modalities of regulating, restricting or even rejecting a fundamental right falling within Article 21 has to be fair, not foolish, carefully designed to effectuate, not to subvert, the substantive right itself. Thus, understood, ‘procedure’ must rule out anything arbitrary, freakish or bizarre. A valuable constitutional right can be canalised only by canalised processes".

When machines and robots are deployed to conduct blanket surveillance and impinge on the most fundamental right to life and liberty and also violate the basic tenets of due process, then much cannot be done by way of procedures. What then do we resort to, is the primary question. Can there be a compromise between the right to privacy and security?

A no-win situation

In reality, dragnet surveillance or blanket surveillance is not very useful for gathering valuable intelligence to prevent instances of threat to national security, public safety and public emergency. For example, if the CMS is used to mine data, analyse content related to anti-social activities and even if the system is 99 per cent accurate, the remaining 1 per cent which is a false positive happens to be a large set. So, 1 out of every 100 individuals identified as an anti-social element by CMS may actually be an innocent citizen. Given the possibility of false positives and which may be more than 1 per cent, the number of innocent citizens caught in the terrorist net would be much higher.

Even though blanket surveillance or dragnet surveillance can keep a tab on everyone, it is nearly impossible for an algorithm to separate the terrorists from the rest. Moreover, the data set collected by the machine is too big for any human analyst, to actually analyze and identify the terrorist in the midst of a deluge of information. Therefore, the argument that a system like CMS will ensure security in lieu of minor intrusions of privacy is a flawed one. Implementation of CMS will not really ensure security but will be a case of blatant violation of individual’s right to privacy anyway.

What is perhaps more shocking is that not only will CMS be futile in preventing security breaches or neutralizing security threats, it will on the contrary expose individual Indian citizens to breach of personal security. If personal data and information are stored for future reference through a centralized mechanism, which is also the case with UID, it will be highly susceptible to attacks and security threats. It will be a Pandora’s Box with a potential to create havoc the moment someone is able to gain access to the information with intention to misuse that. Leaking of personal information and data on a large scale can be detrimental to society and give rise to instances of public emergency.

The ‘Right to be Forgotten’

Currently, the European Union is engulfed in the debate on the “Right to be Forgotten” laws. The Right to be Forgotten finds its origins in the French Law le droit à l’oubli or the right of oblivion, where a convict who has served his sentence can object to the publication of facts of his conviction and imprisonment or penalty. This law has a new found meaning in the context of social media and the internet, where we have the right to delete all our personal information permanently. This is an important issue which India should debate and discuss, as we live in an era where privacy comes at a cost.

On the one hand, technology has made it easier to track, trace, monitor and snoop, on the other it has also seen innovation in the field of encryption and anonymity tools. Encryption tools such as Open PGP exist online, which can secure information from third party access. Tor Browser, allows an user to surf the web anonymously. The use of such technologies should be encouraged as there is no law which prohibits their use. If systems are being built to spy on us, it will be better if we use technologies which protect our personal information from such surveillance technologies.

SEBI and Communication Surveillance: New Rules, New Responsibilities?

This research was undertaken as part of the 'SAFEGUARDS' project that CIS is undertaking with Privacy International and IDRC

Introduction

The Securities Exchange Board of India (SEBI) is the country’s securities and market regulator, an investigation agency which seeks to combat market offenses such as insider trading. SEBI has received much media attention this month regarding its recent expansion of authority; the agency is reportedly on track to be granted powers to access telecom companies’ CDRs. These CDRs are kept by telecommunication companies for billing purposes, and contain information on who sent a call, who received a call, and how long the call lasted, but does not disclose information about call content. Although SEBI has emphatically sought several new investigative powers since 2009 (including access to CDRs, surveillance of email, and monitoring of social media), India’s Ministry of Finance only recently endorsed SEBI’s plea for direct access to service providers’ CDRs. In SEBI’s founding legislation, this capability is not mentioned. Very recently, however, the Ministry of Finance has decided to support expansion of current legislation in regards to CDR access for SEBI, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), and potentially other agencies, when it comes to prevention of money laundering and other economic offenses.

SEBI’s Authority (Until Now)

Established in 1992 under the Securities and Exchange Board of India Act, SEBI was created with the power of "registering and regulating the working of… [individuals] and intermediaries who may be associated with securities markets in any manner."[1] Its powers have included "calling for information from, undertaking inspection, conducting inquires and audits of the intermediaries and self-regulatory organisations in the securities market."[2] Although the agency has held the responsibility to investigate records on market activity, they have never explicitly enjoyed a right to CDRs or other communications data. Now, with the intention of “meeting new challenges thrown forward by the technological and market advances,”[3] SEBI and the Ministry of Finance want to extend their record keeping scope and investigative powers to include CDR access, a form of communications surveillance.

But the ultimate question is whether agencies like SEBI need this type of easy access to records of communication.

What is the Importance of CDR Access?

Reports on SEBI’s recent expansion are quick to ensure that the agency is not looking for phone-tapping rights, which intercepts messages within telephonic calls, but instead only seeks call records. CDRs, in effect, are “metadata,” a sort of information about information. In this case, it is data about communications, but it is not the communications themselves. Currently, there a total of nine agencies which are able to make actual phone-tapping requests in India. But when it comes to access of CDRs, the government seems much more generous in expanding powers of existing agencies. SEBI, as well as RBI and others, are all looking to be upgraded in their authority over CDRs. Experts argue, however, that "metadata and other forms of non-content data may reveal even more about an individual than the content itself, and thus deserves equivalent protection."[4] Therefore, a second crucial question is whether this sensitive CDR data will feature the same detail of protection and safeguards which exist for communication interception.

One reason for the recent move in CDR access is that SEBI and RBI have found the process of obtaining CDRs too arduous and ill-defined.[5] Currently, under section 92 of the CrPc, Magistrates and Commissioners of Police can request a CDR only with an official corresponding first information report (FIR), while there exists no explicit guideline for SEBI’s role in the process of CDR acquisition.[6] Although the government may seek to relax this procedure, SEBI’s founding legislation prohibits investigation without the pretense of “reasonable grounds," as stipulated in section 11C of the SEBI Act.[7] It has always stood that only under these reasonable grounds could SEBI begin inspection of an intermediary’s "books, registers, and other documents."[7] With the government creating a way for SEBI and similar agencies to circumvent the traditional procedures for access to CDRs, these new standards should incorporate safeguards to ensure the protection of individual privacy. Banking companies, financial institutions, and intermediaries have already been obliged to maintain extensive record keeping of transactions, clients, and other financial data under section 12 of the Prevention of Money-Laundering Act of 2002.[8] But books and records containing financial data differ greatly from communication data, which can include much more personal information and therefore may compromise individuals’ freedom of speech and expression, as well as the right to privacy.

Significance and Responsibility in this Decision

Judging from SEBI’s prior capabilities of inspection and inquiry, this change may initially seem only a minor expansion of power for the agency, but it actually represents a significant transition in governmental leniency toward access to private records. As mentioned, the recent goal of the Ministry of Finance to extend rights to CDRs is resulting in amended powers for more agencies than only SEBI. Moreover, this power expansion comes on the heels of controversy surrounding America’s National Security Agency (NSA) amassing millions of CDRs and other datasets both domestically and internationally. There is obvious room for concern over Indian citizen’s call records being made more easily accessible, with fewer checks and balances in place. The benefits of the new policy include easier access to evidence which could incriminate those involved in financial crimes. But is that benefit actually worth giving SEBI the right to request citizen’s call records? In the cases against economic offenses, CDR access often amounts only to circumstantial evidence. With its ongoing battle against insider trading and other financial malpractice, crimes which are inherently difficult to prove, SEBI could have aspirations to grow progressively more omnipresent. But as the agency’s breadth expands, citizen’s rights to privacy are simultaneously being curtailed. Ultimately, the value of preventing economic offense must be balanced with the value of the people’s rights to privacy.

[1]. 1992 Securities and Exchange Board of India Act, section 11, part 2(b).

[2]. 1992 Securities and Exchange Board of India Act, section 11, part 2(i).

[3]. “Sebi Finalising new Anti-money laundering guidelines,” The Times of India, June 16, 2013

[4]. International Principles on the Application of Human Rights to Communications Surveillance -http://www.necessaryandproportionate.net/#_edn1

[5]. “Sebi to soon to get Powers to Access Call Records,” Business Today, June 13, 2013

http://businesstoday.intoday.in/story/sebi-call-record-access/1/195815.html

[6]. 1973 Criminal Procedure Code, Section 92 http://trivandrum.gov.in/~trivandrum/pdf/act/CODE_OF_CRIMINAL_PROCEDURE.pdf

“Govt gives Sebi, RBI Access to Call Data Records,” The Times of India, June 14, 2013

[7]. 1992 Securities and Exchange Board of India Act, section 11C, part 8

[8]. 2002 Prevention of Money-Laundering Act, section 12

Privacy Round Table Kolkata

Invite-Kolkata.pdf

—

PDF document,

1090 kB (1116261 bytes)

Invite-Kolkata.pdf

—

PDF document,

1090 kB (1116261 bytes)

Way to watch

Chinmayi Arun's column was published in the Indian Express on June 26, 2013.

A petition has just been filed in the Indian Supreme Court, seeking safeguards for our right to privacy against US surveillance, in view of the PRISM controversy. However, we should also look closer home, at the Indian government's Central Monitoring System (CMS) and other related programmes. The CMS facilitates direct government interception of phone calls and data, doing away with the need to justify interception requests to a third party private operator. The Indian government, like the US government, has offered the national security argument to defend its increasing intrusion into citizens' privacy. While this argument serves the limited purpose of explaining why surveillance cannot be eliminated altogether, it does not explain the absence of any reasonably effective safeguards.

Instead of protecting our privacy rights from the domestic and international intrusions made possible by technological development, our government is working on leveraging technology to violate privacy with greater efficiency. The CMS infrastructure facilitates large-scale state surveillance of private communication, with very little accountability. The dangers of this have been illustrated throughout history. Although we do have a constitutional right to privacy in India, the procedural safeguards created by our lawmakers thus far offer us very little effective protection of this right.

We owe the few safeguards that we have to the intervention of the Supreme Court of India, in PUCL vs Union of India and Another. In the context of phone tapping under the Telegraph Act, the court made it clear that the right to privacy is protected under the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution of India, and that telephone tapping would also intrude on the right to freedom of speech and expression under Article 19. The court therefore ruled that there must be appropriate procedural safeguards to ensure that the interception of messages and conversation is fair, just and reasonable. Since lawmakers had failed to create appropriate safeguards, the Supreme Court suggested detailed safeguards in the interim. We must bear in mind that these were suggested in the absence of any existing safeguards, and that they were framed in 1996, after which both communication technology and good governance principles have evolved considerably.

The safeguards suggested by the Supreme Court focus on internal executive oversight and proper record-keeping as the means to achieving some accountability. For example, interception orders are to be issued by the home secretary, and to later be reviewed by a committee consisting of the cabinet secretary, the law secretary and the secretary of telecommunications (at the Central or state level, as the case may be). Records are to be kept of details such as the communications intercepted and all the persons to whom the material has been disclosed. Both the Telegraph Act and the more recent Information Technology Act have largely adopted this framework to safeguard privacy. It is, however, far from adequate in contemporary times. It disempowers citizens by relying heavily on the executive to safeguard individuals' constitutional rights. Additionally, it burdens senior civil servants with the responsibility of evaluating thousands of interception requests without considering whether they will be left with sufficient time to properly consider each interception order.

The extreme inadequacy of this framework becomes apparent when it is measured against the safeguards recommended in the recent report on the surveillance of communication by Frank La Rue, the United Nations special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of speech and expression. These safeguards include the following: individuals should have the legal right to be notified that they have been subjected to surveillance or that their data has been accessed by the state; states should be transparent about the use and scope of communication surveillance powers, and should release figures about the aggregate surveillance requests, including a break-up by service provider, investigation and purpose; the collection of communications data by the state, must be monitored by an independent authority.

The safeguards recommended by the special rapporteur would not undermine any legitimate surveillance by the state in the interests of national security. They would, however, offer far better means to ensure that the right to privacy is not unreasonably violated. The emphasis placed by the special rapporteur on transparency, accountability and independent oversight is important, because our state has failed to recognise that in a democracy, citizens must be empowered as far as possible to demand and enforce their rights. Their rights cannot rest completely in the hands of civil servants, however senior. There is no excuse for refusing to put these safeguards in place, and making our domestic surveillance regime transparent and accountable, in compliance with our constitutional and international obligations.

World Wide Rule

Click to read the original published in the Indian Express here

Book: The New Digital Age

Author: Eric Schmidt & Jared Cohen

Publisher: Hachette

Price: Rs 650

Pages: 315

When I first heard that Eric Schmidt the chairman of Google and Jared Cohen, the director of the techno-political think-tank Google Ideas, are co-authoring a book about our future and how it is going to be re-shaped with the emergence of digital technologies, I must confess I was sceptical. When people who do things that you like start writing about those things, it is not always a pretty picture. Or an easy read. However, like all sceptics, I am only a romantic waiting to be validated. So, when I picked up The New Digital Age I was hoping to be entertained, informed and shaken out of my socks as the gurus of the interwebz spin science fiction futures for our times. Sadly, I have been taught my lesson and have slid back into hardened scepticism.

Here is the short version of the book: Technology is good. Technology is going to be exciting. There are loads of people who haven't had it yet. There are not enough people who have figured out how things work. Everybody needs to go online because no matter what, technologies are here to stay and they are going to be the biggest corpus of power. They write, "There is a canyon dividing people who understand technology and people charged with addressing the world's toughest geopolitical issues, and no one has built a bridge…As global connectivity continues its unprecedented advance, many old institutions and hierarchies will have to adapt or risk becoming obsolete, irrelevant to modern society." So the handful who hold the reigns of the digital (states, corporates, artificial intelligence clusters) are either going to rule the world, or, well, write books about it.

The long version is slightly more nuanced, even though it fails to give us what we have grown to expect of all things Google — the bleeding edge of back and beyond. For a lay person, observations that Schmidt and Cohen make about the future of the digital age might be mildly interesting in the way title credits to your favourite movie can be. Once they have convinced us, many, many times, that the internet is fast and fluid and that it makes things fast and fluid and hence the future we imagine is going to be fast and fluid, the authors tell us that the internet is spawning a new "caste system" of haves, have-nots, and wants-but-does-not-haves.

Citing the internet as "the largest experiment involving anarchy in history" they look at the new negotiations of power around the digital. Virulent viruses from the "Middle East" make their appearance. Predictably wars of censorship and free information in China get due attention. Telcos get a big hand for building the infrastructure which can sell Google phones to people in Somalia. The book offers a straightforward (read military) reading of drones and less-than-expected biased views on cyberterrorism, which at least escapes the jingoism that the USA has been passing off in the service of a surveillance state. And more than anything else, the book shows politicos and governments around the world, that the future is messy, anarchy is at hand, but as long as they put their trust in Big Internet Brothers, the world will be a manageable place.

So while you can clearly see where my review for the book is heading, I must give it its due credit.

There are three things about this book that make it interesting. The first is how Schmidt and Cohen seem to be in a seesaw dialogue with themselves. They realise that five billion people are going to get connected online. They gush a little about what this net-universality is going to mean. And then immediately, they also realise that we have to prepare ourselves for a "Brave New World," which is going to be infinitely more messy and scary. They recognise that the days of anonymity on the Web are gone, with real life identities becoming our primary digital avatars. However, they also hint at a potential future of pseudonymity that propels free speech in countries with authoritarian regimes. This oscillation between the good, the bad, the plain and the incredible, keeps their writing grounded without erring too much either on the side of techno-euphoria or dystopic visions of the future.

Second, and perhaps justly so, the book doles out a lot of useful information not just for the techno-neophytes but also the amateur savant. There are stories about "Currygate" in Singapore, or of what Vodaphone did in Egypt after the Arab Spring, or of the "Human Flesh Search Engine" in China, which offer a comprehensive, if not critical, view of the way things are. Schmidt and Cohen have been everywhere on the ether and they have cyberjockeyed for decades to tell us stories that might be familiar but are still worth the effort of writing.

Third, it is a readable book. It doesn't require you to Telnet your way into obscure meaning sets in the history of computing. It is written for people who are still mystified not only about the past of the Net but also its future, and treads a surprisingly balanced ground in both directions. It is a book you can give to your grandmother, and she might be inspired to get herself a Facebook (or maybe a Google +) account.

But all said and done, I expected more. It is almost as if Schmidt and Cohen are sitting on a minefield of ideas which they want to hint at but don't yet want to share because they might be able to turn it into a new app for the Nexus instead. It is a book that could have been. It wasn't. It is ironic how silent the book is about the role that big corporations play in shaping our techno-futures, and the fact that it is printed on dead-tree books with closed licensing so I couldn't get a free copy online. For people claiming to build new and political futures, the fact that this wisdom could not come out in more accessible forms and formats, speaks a lot about how seriously we can take their views of the future.

A Technological Solution to the Challenges of Online Defamation

This blog post written by Eduardo Bertoni was published in GlobalVoices on May 28, 2013. CIS has cross-posted this under the Creative Commons Licence.

Consider this scenario:

A public figure, let’s call her Senator X, enters her name into a search engine. The results surprise her — some of them make her angry because they come from Internet sites that she finds offensive. She believes that her reputation has been damaged by certain content within the search results and, consequently, that someone should pay for the personal damages inflicted.

Her lawyer recommends appealing to the search engine – the lawyer believes that the search engine should be held liable for the personal injury caused by the offensive content, even though the search engine did not create the content. The Senator is somewhat doubtful about this approach, as the search engine will also likely serve as a useful tool for her own self-promotion. After all, not all sites that appear in the search results are bothersome or offensive. Her lawyer explains that while results including her name will likely be difficult to find, the author of the offensive content should also be held liable. At that point, one option is to request that the search engine block any offensive sites related to the individual’s name from its searches. Yet the lawyer knows that this cannot be done without an official petition, which will require a judge’s intervention.

“We must go against everyone – authors, search engines – everyone!” the Senator will likely say. “Come on!” says the lawyer, “let's move forward.” However, it does not occur to either the Senator or the lawyer that there may be an alternative approach to that of classic courtroom litigation. The proposal I make here suggests a change to the standard approach – a change that requires technology to play an active role in the solution.

Who is liable?

The “going against everyone” approach poses a critical question: Who is legally liable for content that is available online? Authors of offensive content are typically seen as primarily liable. But should intermediaries such as search engines also be held liable for content created by others?

This last question raises a very specific, procedural question: Which intermediaries will be the subjects of scrutiny and viewed as liable in these types of situations? To answer this question, we must distinguish between intermediaries that provide Internet access (e.g. Internet service providers) and intermediaries that host content or offer content search functions. But what exactly is an ‘intermediary’? And how do we evaluate where an intermediary’s responsibility lies? It is also important to distinguish those intermediaries which simply connect individuals to the Internet from those that offer different services.

What kind of liability might an intermediary carry?

This brings us to the second step in the legal analysis of these situations: How do we determine which model we use in defining the responsibility of an intermediary? Various models have been debated in the past. Leading concepts include:

- strict liability, under which the intermediary must legally respond to all offensive content

- subjective liability, under which the intermediary’s response depends on what it has done and what it was or is aware of

- conditional liability – a variation on subjective liability – under which, if an intermediary was notified or advised that it was promoting or directing users to illegal content and did nothing in response, it is legally required to respond to the offensive content.

These three options for determining liability and responses to offensive online content have been included in certain legislation and have been used in judicial decisions by judges around the world. But not one of these three alternatives provides a perfect standard. As a result, experts continue to search for a definition of liability that will satisfy those who have a legitimate interest in preventing damages that result from offensive content online.

How are victims compensated?

Now let’s return to the example presented earlier. Consider the concept of Senator X’s “satisfaction.” In these types of situations, “satisfaction” is typically economic — the victim will sue for a certain amount of money in “damages”, and she can target anyone involved, including the intermediary.

Interestingly, in the offline world, alternatives have been found for victims of defamation: For example, the “right to reply” aims to aid anyone who feels that his or her reputation or honor has been damaged and allows individuals to explain their point of view.

We must also ask if the right to reply is or is not contradictory to freedom of expression. It is critical to recognize that freedom of expression is a human right recognized by international treaties; technology should be able to achieve a similar solution to issues of online defamation without putting freedom of expression at risk.

Solving the problem with technology

In an increasingly online world, we have unsuccessfully attempted to apply traditional judicial solutions to the problems faced by victims like Senator X. There have been many attempts to apply traditional standards because lawyers are accustomed to using in them in other situations. But why not change the approach and use technology to help “satisfy” the problem?

The idea of including technology as part of the solution, when it is also part of the problem, is not new. If we combine the possibilities that technology offers us today with the older idea of the right to reply, we could change the broader focus of the discussion.

My proposal is simple: some intermediaries (like search engines) should create a tool that allows anyone who feels that he or she is the victim of defamation and offensive online content to denounce and criticize the material on the sites where it appears. I believe that for victims, the ability to say something and to have their voices heard on the sites where others will come across the information in question will be much more satisfactory than a trial against the intermediaries, where the outcome is unknown.

This proposal would also help to limit regulations that impose liability on intermediaries such as search engines. This is important because many of the regulations that have been proposed are technologically impractical. Even when they can be implemented, they often result in censorship; requirements that force intermediaries to filter content regularly infringe on rights such as freedom of expression or access to information.

This proposal may not be easy to implement from a technical standpoint. But I hope it will encourage discussion about the issue, given that a tool like the one I have proposed, although with different characteristics, was once part of Google’s search engine (the tool, “Google Sidewiki” is now discontinued). It should be possible improve upon this tool, adapt it, or do something completely new with the technology it was based on in order to help victims of defamation clarify their opinions and speak their minds about these issues, instead of relying on courts to impose censorship requirements on search engines. This tool could provide much greater satisfaction for victims and could help prevent the violation of the rights of others online as well.

Critics may argue that people will not read the disclaimers or statements written by “defamed” individuals and that the impact and spread of the offensive content will continue unfettered. But this is a cultural problem that will not be fixed by placing liability on intermediaries. As I explained before, the consequences of doing so can be unpredictable.

If we continue to rely on traditional regulatory means to solve these problems, we’ll continue to struggle with the undesirable results they can produce, chiefly increased controls on information and expression online. We should instead look to a technological solution as a viable alternative that cannot and should not be ignored.

Eduardo Bertoni is the Director of the Center for Studies on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information at Palermo University School of Law in Buenos Aires. He served as the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression to the Organization of American States from 2002-2005.

Indian surveillance laws & practices far worse than US