Telecom Main

How the Telecom Act undermines personal liberties

The Telecommunications Act cements government’s power to suspend internet services, does not establish independent oversight mechanism for interception, suspension orders. The article originally published in the Indian Express can be read here.

“Is Big Brother watching you? At the press of a button a civil servant can inspect just about every detail of your life your tax, your medical record and periods of unemployment. That civil servant could be your neighbour. There is mounting concern over this powerful weapon that the computer revolution has put in the government’s hand. But no civil servant will be allowed to examine personal files from another department, without written authority from a Minister. I shall be announcing legislation enabling citizens to take action against any civil servant who gains unauthorised access to his file.” (Yes Minister). The year is 1980, the computer revolution is just about beginning and questions of surveillance have become pertinent; safeguards in the form of separation of powers between the executive and legislative are announced by the Minister for the protection of citizens.

Although theatrical, Yes Minister can yet be invoked to characterise governments in most parliamentary democracies especially India’s.

More than four decades on, the Indian Parliament witnessed the smooth passage of several pieces of legislation, including the Telecommunications Act (TA) 2023, which justifiably seeks to bury remnants of colonial-era laws. While the modern digital age creates conditions for unprecedented surveillance reflecting the Benthamite tenet of maximum monitoring at minimum cost, the question on everyone’s minds is whether the law has enough safeguards and an independent regulatory architecture to protect the rights of citizens.

Before contemplating this weighty query, let us set the narrative in context with a quick recap of the major markers in digital governance in India that have concluded, at least for the moment, in the passing of TA 2023.

The institutional regime for telecommunications dates back to the late 1990s and was created more by accident and less by design. The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) became necessary because private sector investment came in when the public sector operator was both player and referee. Massive litigation followed, leading to the setting up of TRAI. Within a few years, the Telecom Dispute Settlement Appellate Tribunal (TDSAT) was carved from TRAI to fast-track excessive litigation. In between, there was the dissolution of the first TRAI, only confirming who the “boss” was.

The desire to serve in regulatory regimes has surely been tainted by the goal of securing sinecures. This is not just an Indian phenomenon. For example, the Biden administrators wish they continue in office for long. It is in the nature of such positions that many of those appointed will never again be in a position of authority. There have been few instances after its dissolution that TRAI has taken on the government. The relationship between the legislature and the executive is complex but suffice it to say that such a separation in telecom is met much more in the breach.

The regulatory regime for telecom described above notifies subordinate legislation, enforces and adjudicates disputes — it performs the role of the executive and the adjudicator. One key safeguard for the protection of ordinary citizens is, therefore, already undermined. The separation of powers remains on paper and the exercise of authority through delegated rule-making ensures the government can intervene with little resistance.

In this background, TA 2023 poses challenges. Although undoing colonial-era laws is one of the stated goals, the re-purposing of some existing provisions and ambiguous drafting does little justice to that aim. For example, the definition of telecommunication services has been left open to interpretation. Internet-based services like WhatsApp and Gmail are, therefore, likely to fall under the Act’s ambit. Provisions empowering the government to notify standards and conformity measures or ask for alternatives to end-to-end encryption such as client-side scanning could undermine privacy. Further requiring messages to be disclosed in an “intelligible format” is irreconcilable with end-to-end privacy engineering. Tinkering with end-to-end encryption for compliance could create potential points of vulnerability.

The grounds on which such information may be sought, outlined in Section 20 (2) include sovereignty and integrity of India, security of the state and public order. Prima facie these appear reasonable. However, the current phrasing leaves room for expansive interpretation by overenthusiastic enforcement machinery — it could go beyond the letter of the law to please political masters. Research conducted in 2021 by Vrinda Bhandari and others found that many orders issued under the guise of public order restrictions would not qualify as legal per se. The Act cements the government’s power to suspend internet services (Section 20(2)(b)) and does not include procedural safeguards envisaged in the Supreme Court’s Anuradha Bhasin judgment such as the proportionality test, exploration of suitable alternatives and the adoption of least intrusive measures.

The Act also does not establish an independent oversight mechanism for interception and suspension orders related to telecommunications. These rules, framed in 1996 in line with the directions of the Supreme Court in PUCL v. Union of India and requiring a committee consisting exclusively of senior government officials, reflect inadequate separation. In the UK the law mandates approval of interception warrants by judicial commissioners. Separation of powers is however not a panacea; it is just a necessary condition for the effective functioning of institutions. We must also observe the counsel of John Stuart Mill for the maintenance of institutional integrity namely, not “to lay [their] liberties at the feet of even a great man, or to trust him with powers which enable him to subvert [their] institutions” — JS Mill, quoted by BR Ambedkar on November 25 1949, requoted by sitting Chief Justice of India on Constitution Day (November 26, 2018).

Kathuria is Dean, School of Humanities and Social Sciences and Professor of Economics at the Shiv Nadar Institution of Eminence and Suri is Research Lead, CIS.

Comments to the Telecommunications Bill, 2023

The comments were reviewed by Tanveer Hasan. Click to download the PDF

Key concerns

Definition of Telecommunication Service

The definition of the terms telecommunication (section 2(p) and telecommunication service (section 2(t)) is extremely broad and would effectively include transmission of any signal by any electromagnetic systems. This wide definition increases the scope of the Bill to include almost all kinds of means of communication used in modern times including messaging services, email, OTT services, among others. Even if one were to accept the argument that the scope of the Bill has been deliberately kept wide so that the government has the power to regulate all means of telecommunication in order to prevent mischief and illegal activities, the problem arises with the onerous language of section 3(1) which makes it compulsory to obtain an authorisation from the Central Government for any and all telecommunication services, unless specifically exempted under section 3(3).

In simpler words the Bill not only seeks to regulate all communication services, but requires government permission to provide such services in the first place. Such an approach has the very likely potential to hamper future telecom innovation especially in light of the fact that the penalty for not obtaining permission is imprisonment upto 3 years as well as fine of upto Rs. 2 crores.

Such a wide definition leads to ambiguity and lack of regulatory certainty to businesses as well as users participating in the ecosystem. This proposal triggers immediate concerns, particularly a confusing definition of telecommunication services which may also incorporate the provision of a broad range of digital and online services. Such a wide definition could lead to confusion and arbitrary implementation on one hand, and if made applicable to the content layer of the internet architecture stifle innovation in the digital ecosystem due to onerous licensing/registration requirements on the other hand. It is also pertinent to note that some of the internet-based services listed in the definition in 2(21) are already regulated under the Information Technology (IT) Act 2000. For example, the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 regulates intermediaries, including the significant social media intermediaries (SSMI) such as Facebook and Twitter. Putting an additional regulatory burden on these service layer companies will hamper innovation and competitiveness of the sector and also amount to regulatory overreach.

Power of authorisation and assignment

Section 3 (7) - Any authorised entity which provides such telecommunication services as may be notified by the Central Government, shall identify the person to whom it provides telecommunication services through use of any verifiable biometric based identification as may be prescribed.

All services do not require a biometric based identification of the person. While there is a legitimate need to verify a person in the case of financial transactions, however a similar level of scrutiny is not warranted for applications that a person might use once, or applications that do not pose a threat. For example the need to verify a person through Know Your Customer (KYC) or otherwise for an application to order food, or an application which is meant for communication can be excessive regulation. In addition to the enhanced burden of collecting and storing this data that will come on the telecommunication service, there will also be the added requirement to maintain strict data protection and security measures under the Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023. Furthermore, as has been seen in multiple instances of data breaches and cyber security attacks such as the one at AIIMS[1], Justpay[2] demonstrate that both public and private organisations can be affected by cyber attacks. It is therefore advisable to reduce the number of entities that store and collect sensitive personal data such as biometric information in the interest of privacy as well as national security.

The Supreme Court while looking at the constitutionality of the Aadhaar Act upheld the need for banking and financial institutions to require an individual’s Aadhaar number stating the legitimate aim of preventing money laundering; however, the Court struck down the provision that required any private entity to collect Aadhaar details. Justice Bhushan held that the collection by private entities violated the right to privacy, by failing the first prong of the test laid down in Puttaswamy judgement, the test of legality.[3]

More importantly, through the requirement of ‘verifiable biometric based identification’, the Bill is likely to nudge telecom service providers to incorporate Aadhar Based identification, even though the Indian Supreme Court in 2018 held that the mandatory linking of mobile connections with biometric identification is unlawful.

Standards, Public Safety, National Security and Protection of Telecommunication Networks

Power to notify standards

Section 19 (f) The power to notify standards and conformity measures on encryption is a sweeping power that allows the central government to potentially request for backdoors on encryption, or ask for alternatives to end to end encryption such as client side scanning, which have been critiqued[4] as measures that undermine privacy for all users. If the objective is to provide recommendations for certain encryption techniques when dealing with sensitive government data, a more specific compliance certification can be issued to such firms. For example, the United States government mandates certain government agencies to comply with the Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS)[5] which also apply to non-government firms holding government contracts. Standards like FIPS recommend specific cryptographic modules to ensure secure communication of sensitive data. Such conditions and cases must be explicitly scoped in defining the standard setting powers of government with regard to encryption, in consultation with the industry and civil society organisations.

Provisions for public emergency or public safety

Section 20(2) (a) - Messaging apps such as WhatsApp and Signal enable end to end encryption, where messages are encrypted on endpoints such as user devices. Service providers and intermediaries cannot decrypt messages. Requiring messages to be amenable to disclosure in an 'intelligible format' is technically impossible within the end to end paradigm of privacy engineering[6]. Technical means of disclosing the contents of messages can either reside on a user’s device, in a middle-box that mediates communication, or on servers where some computation can occur. Restructuring end-to-end encrypted communication networks to facilitate these technical means of disclosure would result in the creation of potential points of vulnerability and encryption backdoors. These vulnerabilities can be exploited by malicious actors and backdoors act as ‘intentional vulnerabilities’[7] that can be used for excessive surveillance of communication that users believe to be private.

Section 20 (2) states the grounds for which such information may be sought. These include sovereignty and integrity of India, defence and security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, and public order. Prima facie, these may appear to be reasonable grounds for facilitating government access, however, the current phrasing is too wide and leaves room for an expansive interpretation. This is particularly true for maintenance of “public order” that is routinely invoked in a variety of situations.[8] According to research conducted in 2021 by Vrinda Bhandari and others on the “Use and Misuse of Section 144 found orders issued under the guise of public order restrictions to regulate a variety of activities, many of which would not qualify as illegal activities per se. For instance, orders were issued to prohibit flying of hot air balloons, unmanned aerial vehicles, unmanned aircraft systems, use of “special” or “metallic” manjhas to fly kites and carrying tiffin boxes inside cinemas.[9] And tracing encrypted messages to thwart such perceived public order threats would be excessive and disproportionate. The order to intercept, detain, disclose or suspend a communication made between private individuals, acts as a violation of privacy and provides extensive grounds to surveil people.[10]

These grounds may be used to intercept or monitor all communication where a particular word or set of words is used. And its implementation would require communication of all users to be monitored effectively leading to a lower degree of privacy for all users[11] - including internet communication based apps due to definitional ambiguity. The Supreme Court has held that any infringement of the right to privacy should be proportionate to the need for such interference.[12] The judgement in the Puttaswamy case provides some guidance to assess the limits and scope of the constitutional right to privacy in the form of the three prong test. The test requires the existence of a law, a legitimate state interest and the restriction (to privacy) should be ‘proportionate'. This provision violates a user’s fundamental right to privacy since it fails to meet the proportionality requirement as laid down by the Supreme Court.

Section 20 (2) (b) provides for suspension of telecommunication service or class of services on similar grounds. The Bill empowers the DoT to suspend telecommunication services and if applicable to internet based communication services such as WhatsApp, Signal, among others without the need for any judicial oversight or procedural safeguards as enunciated by the Supreme Court in Anuradha Bhasin vs Union Of India. The provision must incorporate an independent oversight mechanism for such orders and also incorporate safeguards laid down by the Supreme Court in the Anuradha Bhasin judgement[13] to prevent arbitrary, frequent, and prolonged suspension of telecommunication services in India.

Protection of users

Measures for protection of users

Section 28 - This section should also provide mechanisms for de-registering from “specific messages” . While this section mentions the need for prior consent of users for receiving the specified messages/ class of specified messages, it should look at the full spectrum of rights the Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023 provides, which includes the right to withdraw consent. Hence we suggest that Section 28(3) adds that the authorised entity providing telecommunication services shall establish an online mechanism for withdrawal of consent, in addition to grievance redressal.

Duty of users

Section 29 - While listing out the duties of the users the Act puts the onus on the user to furnish correct information. It fails to take into account instances where the information is fed into the system by third parties, due to issues of access and literacy on the part of the users. While the section heading states “duty of the user” the preceding text “no user shall” has the potential to penalise users for acts carried out without a malicious intent. Additionally, there is also a need to look at how notices and terms and conditions of most telecommunication services are primarily in English, making it even more difficult for a large number of Indian users to read and hence understand the requirements. Furthermore, the associated penalty for failing to comply with these provisions are, i.e. up to INR 25,000 for the first offence and for the second or subsequent offences, up to INR 50,000 for every day till the contravention continues. Considering the low digital literacy rates, the government would be well advised to reconsider imposition of such hefty fines.

If applicable on internet based services, this will also impact the ability of a user to retain anonymity over the internet. Individuals may choose to remain anonymous online for a number of reasons. It is important to understand that an individual may remain anonymous for a variety of legitimate purposes such as expressing opinions about their employers and whistleblowers, providing anonymous tips to newspapers or law enforcement, expressing political opinions and criticism that may be subject to persecution, or simply someone saying something that they may be embarrassed about. [14] In India, in particular, an individual’s caste can be identified from their name, and they may choose to remain anonymous or adopt a pseudonym to escape centuries of stigma and discrimination that their communities have faced. The broad definition of telecommunication services as elaborated above places restrictions on anonymity online and severely degrades an individual’s ability to exercise their fundamental right to freedom of expression.

[1]Business Today Desk, “Cyber attack at AIIMS Delhi: Hackers demand Rs 200 cr in crypto, says report” Business Today, 22 November 2022, https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/in-focus/story/cyber-attack-at-aiims-delhi-hackers-demand-rs-200-cr-in-crypto-says-report-354475-2022-11-28.

[2]Ashwin Manikandan, Anandi Chandrashekhar, “Juspay Data Leak fallout: RBI swings into action to curb cyberattacks”, The Economic Times, 6 January 2021, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/technology/juspay-data-leak-fallout-rbi-swings-into-action-to-curb-cyberattacks/articleshow/80125430.cms

[3] “Judgement in Plain English Constitutionality of Aadhaar Act”, “Supreme Court Observer, accessed 22 December 2023,https://www.scobserver.in/reports/constitutionality-of-aadhaar-justice-k-s-puttaswamy-union-of-india-judgment-in-plain-english/

[4] “Why Adding Client-Side Scanning Breaks End-To-End Encryption”, The Electronic Freedom Foundation, accessed 22 December 2023, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/11/why-adding-client-side-scanning-breaks-end-end-encryption.

[5] “Compliance FAQs: Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS)”, NIST, accessed December 22 2023. https://www.nist.gov/standardsgov/compliance-faqs-federal-information-processing-standards-fips

[6] “Personal Data in the Cloud Is Under Siege. End-to-End Encryption Is Our Most Powerful Defense.”, Lawfare, accessed 22 December 2023, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/personal-data-in-the-cloud-is-under-siege.-end-to-end-encryption-is-our-most-powerful-defense

[7] “Breaking Encryption Myths”, Global Encryption Coalition, accessed 22 December 2023, https://www.globalencryption.org/2020/11/breaking-encryption-myths/

[8] Smriti Parsheera “Political misinformation is a problem. But asking WhatsApp to risk user privacy is the wrong solution”, The Indian Express, October 28 202 https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/editorials/remedy-worse-than-malaise-9002600/.

[9] Vrinda Bhandari, et al, The Use and Misuse of Section 144 Cr.P.C, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID4404496_code2801004.pdf?abstractid=4389147&mirid=1&type=2

[10]CIS’ Comments to the (Draft) Indian Telecommunication Bill 2022 “Centre for Internet and Society, accessed 22 December 2023 https://cis-india.org/telecom/blog/cis-comments-to-draft-indian-telecom-bill-2022#:~:text=Comment%3A%20The%20draft%20bill%20attempts,power%20over%20the%20local%20government.

[11] The Telecommunications Bill, 2023, PRS Legislative Research, accessed 22 December 2023, https://prsindia.org/billtrack/the-telecommunication-bill-2023

[12] Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd) vs Union of India, W.P.(Civil) No 494 of 2012, Supreme Court of India, September 26, 2018.

[13] Writ Petition (Civil) NO. 1031 OF 2019, accessed 22 Decmber 2023, https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2019/28817/28817_2019_2_1501_19350_Judgement_10-Jan-2020.pdf.

[14]Palme, Jacob, and Mikael Berglund. "Anonymity on the Internet." Accessed 22 December 2023: 2009.

CIS’ Comments to the (Draft) Indian Telecommunication Bill 2022

Preliminary

The Centre for Internet and Society (CIS) is a non-profit organization that undertakes interdisciplinary research on the internet and digital technologies from policy and academic perspectives. Through its diverse initiatives, CIS explores, intervenes in, and advances contemporary discourse and practices around the internet, technology, and society in India, and elsewhere. Over the last decade, CIS has worked extensively on policy issues related to telecommunication, internet access, digital inclusion, and so on.

In the past, CIS has responded to various public consultations pertaining to telecommunication such as the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) consultation on 5G Auctions[1], TRAI consultation on regulation of over-the-top (OTT) services[2], to name a few .

We appreciate the efforts of the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) for having consultation on the “Draft Indian Telecommunication Bill 2022”. We are grateful for the opportunity to put forth our views and comments to the draft bill.

Summary of Recommendations

- At the outset, we recommend that in the interest of transparency and accountability, prior to enacting important legislations like the Telecom Bill, the government would be well-advised to conduct an “impact assessment” exercise such as “regulatory impact assessment” and put the report in public as practised in jurisdictions such as the European Union.[3] We would also recommend the government to disclose responses and submissions that it receives during the process to ensure a transparent and consultative process of policymaking.

- We recommend that the scope of the bill should be reconsidered and internet-based services should be removed from the definition of telecommunication services. From this definition read with other clauses of the bill, it appears that the bill tries to licence (or control !) not just telecommunication but all kinds of communication and internet-based services. Putting onerous regulatory requirements on every bit and byte flowing through the internet is unnecessary and regulatory overreach.

- The draft bill’s attempt to provide for a non-discriminatory and an affordable Right-of-way (RoW) regime is appreciable. However, the central government has been given an overriding power over the local government which has constitutional powers with regard to permissions in their jurisdiction. The bill must clarify the modalities to ensure coordination between centre, state, and local authorities.

- We recommend that clause 46 of the draft bill which significantly dilutes TRAI’s power should be deleted. Moreover, the government must work towards further strengthening TRAI by hiring subject matter experts to ensure that India has a powerful sector regulator which is well prepared to usher in the next wave of innovation.

- We recommend that the Bill be inline with the Puttaswamy Judgement, and that of Anuradha Bhasin vs Union of India. The Bill, while paying close attention to the protection of users and duty of the user, fails to uphold rights of the user such as the right to privacy and the freedom of speech and expression.

- As per clause 29, the objectives for which Telecommunication Development Fund (TDF) can be utilised is broad and therefore the government would be well-advised to specify that TDF can only be utilised to ensure digital access, adoption and usage for digitally marginalised groups. Furthermore, TDF must be ring fenced and not credited to the Consolidated Fund of India to ensure timely implementation which has thus far remained a significant challenge with the universal funds (USOF) regime.

- The bill does not have any provisions upholding the principles of net neutrality. The government must act on TRAI’s recommendations and set up the multistakeholder body to check adherence to net neutrality requirements by incorporating provisions to that effect.

- In the interest of transparency and accountability, a clause requiring the government to report (quarterly or annually) vital statistics relating to the functioning and financial aspects of matters contained within the draft legislation. The reporting should also include the number of licences provided, licences revoked, number of blocking and suspension orders passed among others.

Detailed Response

Preamble |

No comments

Chapter 1: Short Title, Extent and Commencement |

No comments

Chapter 2: Definitions |

➔ 2(9): “message” means any sign, signal, writing, image, sound, video, data stream or intelligence or information intended for telecommunication.

Comment: The terms “intelligence” and “data stream” are not clear in the definition and these terms have not been defined elsewhere in the bill. Moreover, the definition of message is broad and may have implications with regard to surveillance and privacy of users, when read with clause 4(8) and clause 24(2)(a).

Recommendation: We recommend that the terms “intelligence” and “data stream” are defined under the bill, in order to reduce chances of excessive surveillance and to maintain the informational privacy of the individual. Additionally the definition could have an expansive list of what could constitute a message in order to prevent mission creep.

➔ 2(18): “telecommunication equipment” means any equipment, appliance, instrument, device, material or apparatus, including customer equipment, that can be or is being used for telecommunication, and includes software integral to such telecommunication equipment;”

Comment: The inclusion of customer equipment in the definition of telecommunication equipment has implications. The definition of the “customer equipment”[4] as provided in clause 2(5) of the Bill is broad enough to include personal devices such as phones, routers, among others. As per clauses 23 to 26 the Central Government has wide ranging powers with respect to telecommunications equipment and telecommunications networks such as issuing various directions for telecommunications networks and even has the power to take over such networks. As the definitions currently stand, these provisions would automatically become applicable to customer equipment as well which may be a violation of the right to privacy of the citizens of the country.

Moreover, according to 3(2)(c), possession of wireless equipment requires authorization. On reading 3(2)(c) with the definitions of wireless equipment in 2(23) and customer equipment in 2(5), an argument could be framed that the customer equipment could technically also require a licence, and so would the software integral to such equipment. If customer equipment is in fact included in telecom equipment and software integral to it is also included therein, then arguably even Android OS or other OS can be licensable.

Recommendation: Thus, we suggest that the government should remove customer equipment from the definition of telecommunication equipment.

➔ 2(21): “telecommunication services" means service of any description (including broadcasting services, electronic mail, voice mail, voice, video and data communication services, audiotex services, videotex services, fixed and mobile services, internet and broadband services, satellite based communication services, internet based communication services, in-flight and maritime connectivity services, interpersonal communications services, machine to machine communication services, over-the-top (OTT) communication services) which is made available to users by telecommunication, and includes any other service that the Central Government may notify to be telecommunication services;”

Comment: Clause 2(21) expands the scope of “telecommunication services” significantly. The overly-broad definition of “telecommunication services”, and what constitutes a “message”[5], brings within its ambit a host of internet services including but not limited to email, instant messaging, social media services, and even payments and e-commerce transactions. Neither the bill, nor the accompanying explanatory note provides a satisfactory rationale for an all-encompassing definition of “telecommunication services”. The explanatory note attached to the bill suggests that legislations in Australia, EU, UK, Singapore, Japan, and USA have been examined while drafting this bill. However, our research[6] suggests that none of these jurisdictions define “telecommunication services” so expansively and seek to regulate entities offering only internet based services companies through licensing, in particular. It may also be worthwhile to note that TRAI recommended against such an approach and also clarified that there is no issue of financial arbitrage.[7] However, the bill attempts to bring OTT communication services within the purview of licensing. From this definition read with other clauses of the bill, it appears that the bill tries to licence (or control !) not just telecommunication but all kinds of communication and internet-based services. Putting onerous regulatory requirements on every bit and byte flowing through the internet is unnecessary and regulatory overreach. There can be major implications of expanding the definition of telecommunication services, some of which are listed below:

● The draft bill has stringent provisions on surveillance and shutdowns [clause 23 to clause 28]. These clauses would be naturally applicable to the expanded bucket of telecommunication services. This has serious implications on user’s right to privacy and freedom of expression online. For example, the bill gives the government the power to surveil citizens over apps such as WhatsApp, Telegram, to name a few, and even email. [some of this will be delved into greater detail in the foregoing sections]

● Some of the internet-based services listed in the definition in 2(21) are already regulated under the Information Technology (IT) Act 2000. For example, the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 regulates intermediaries, including the significant social media intermediaries (SSMI) such as Facebook and Twitter. Putting an additional regulatory burden on these service layer companies in the form of licensing, as envisaged in clause 3 and clause 4 of the bill would hamper the innovation in the sector. Furthermore, it has been observed that the compliance burden of regulations is higher on small businesses in cases where regulations impose identical requirements on entities regardless of the firm size.[8] Therefore, inserting such a requirement would have a detrimental impact on innovation because excessive compliance requirements would act as a significant entry barrier for smaller firms.

Moreover, there is significant overlap between various services that are mentioned in the definition of telecommunication services which may lead to significant challenges. As these services are not defined elsewhere in the bill, it leaves scope for ambiguity. The bill makes a mention of “over-the-top (OTT) communication services” without defining it. We argue that making a distinction between communication and non-communication OTT services is superficial and does not take into account today’s realities where categorising applications into different categories is extremely difficult. A majority of the OTT applications such as e-commerce, healthcare, food delivery, payments, and so on, provide integrated communication channels. Disaggregation and making an artificial distinction of such apps into communication (with licensing requirements) and non-communication (without licensing requirements) would result in fragmentation of the internet which is definitely not a desirable outcome.

|

The “same-service same-rules” argument put forth by Telecommunication Service Providers (TSPs/ telcos) for the regulation of OTT apps which provide communication services [generally referred to as OTT communication services] at par with them is flawed for the reasons elaborated herein below: ● It is well recognized that there are significant differences at the technical and architectural level between TSPs and OTT apps which provide communication services . Regulating OTT apps which provide communication services at par with TSPs just on the basis of functionality without considering the inherent technical and architectural differences between them is a definite recipe for failure. ● Moreover, even at the functional level, OTT communication apps offer several additional features which are not available in the traditional TSP services.[9] Due to this, establishing functional equivalence between TSP’s services and OTT communication services is not only technically unfeasible but also unnecessary since those apps are better regulated by MEITY. ● Furthermore, TSPs enjoy privileges which OTTs don't. For example, TSPs have exclusive rights to spectrum, right of Way (RoW), numbering resources, to name a few. TSPs have control over underlying broadband infrastructure which OTTs and other internet-based service companies do not have. |

As opposed to what has been suggested in the bill i.e, licence all telecommunication services [clause 3(2)(a)] including the internet-based services, it may be prudent to explore alternative approaches to regulate this space. For instance, a “two-layered framework”[10] for regulatory intervention can be considered. In this two-layered framework, the first layer would be the network layer consisting of the network and infrastructure; and the second layer would be the service layer consisting of applications and services. The services in the second layer can be further refined into the following three categories: (i) services provided over a non-Internet Protocol (IP) based architecture e.g Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN) voice calls provided over a circuit switched network; (ii) specialised services that are provided over an IP based architecture in a closed network including facility-based services e.g., facilities-based VoLTE calls to PSTN and IPTV; (iii) IP-based/ Internet-based services such as OTTs. The gist[11] of the framework is:

- The network layer may be regulated by way of licensing.

- Non-IP Services and Specialised services may be regulated by way of licensing.

- Internet-based services should be regulated by instruments other than licensing. Such instruments should preferably be in the form of legislations like the IT Act and its rules thereunder.

While there can be approaches apart from the one described above to regulate internet-based services such as the OTT and those approaches can be discussed and debated, putting licensing requirements for every internet-based service is not the way forward.

Recommendation: We recommend that the scope of the bill should be reconsidered and internet-based services should be removed from the definition of telecommunication services. In the interest of transparency and accountability, prior to enacting such a legislation the government would be well-advised to conduct a “regulatory impact assessment” exercise and put the report in public, as done in jurisdictions such as the European Union.

Chapter 3: Licensing, Registration, Authorization and Assignment |

Clause 4. Licensing, Registration Authorization and Assignment

➔ 4(6): “The possession and use of any equipment that blocks telecommunication is prohibited, unless authorised by the Central Government for specific purposes.”

Comment: While assuming jurisdiction over equipment capable of blocking telecommunication via this clause is a welcome step, it is not clear why equipment capable of intercepting telecommunications has been kept out of the scope of this clause. Since unlawful and unauthorised interception of telecommunications is a violation of the fundamental right to privacy of an individual,[12] it is imperative that the scope of this clause be increased to include interception equipment as well. Furthermore, the latter part of the provision mentions “specific purposes” without adequate checks and balances in place. As such, the specific purposes must be defined exhaustively to ensure that this power is not misused.

➔ 4(7): "Any entity which is granted a licence under sub-clause (2) of clause 3, shall unequivocally identify the person to whom it provides services, through a verifiable mode of identification as may be prescribed."

Comment: All services do not require a verification of the identity of a person. There is a legitimate need to verify a person in the case of financial transactions, however a similar level of scrutiny is not warranted for applications that a person might use once, or applications that do not pose a threat to anyone. For example the need to verify a person through Know Your Customer (KYC) or otherwise for an application to order food, or an application which is meant for communication can be excessive regulation. Furthermore, number based internet communication apps such as Whatsapp require users to sign in through a mobile number, which have already gone through a KYC process. Therefore, dual KYC would be redundant and serve no purpose.

The Supreme Court while looking at the constitutionality of the Aadhaar Act upheld the need for banking and financial institutions to require an individual’s Aadhaar number stating the legitimate aim of preventing money laundering; however, the Court struck down the provision that required any private entity to collect Aadhaar details.[13] Justice Bhushan held that the collection by private entities violated the right to privacy, by failing the first prong of the test laid down in Puttaswamy, the test of legality.[14]

Recommendation : Clause 4(7) should be deleted.

➔ 4(8) “The identity of a person sending a message using telecommunication services shall be available to the user receiving such message, in such form as may be prescribed, unless specified otherwise by the Central Government.”

Comment: Although the intent behind this provision may have been to curb the menace of anonymous harassment of users, a blanket requirement to reveal the identity of the sender of a message in every instance may be considered a violation of the right to privacy of the sender. . There are clearly a number of competing rights involved here and the issue needs to be addressed in a more nuanced manner. Additionally there are a number of services such as chat applications providing support for mental health, that allow users to be anonymous in order to remove the concern and stigma around seeking help. A requirement that the user's name be revealed in these applications could hinder the functioning of these services as well as prevent more people from seeking help.

Anonymity was also explained in the Puttaswamy Judgment where it was stated that - “Privacy involves hiding information whereas anonymity involves hiding what makes it personal. An unauthorised parting of the medical records of an individual which have been furnished to a hospital will amount to an invasion of privacy.” In his judgement, Justice F. Nariman talks about different aspects of the right to privacy in the Indian context and observes “Informational privacy which does not deal with a person’s body but deals with a person’s mind, and therefore recognises that an individual may have control over the dissemination of material that is personal to him. Unauthorised use of such information may, therefore lead to infringement of this right”.[15]

In this backdrop it is perhaps preferable that the issue be addressed through separate guidelines rather than through a blanket direction in the Statute. Recently the Department of Telecom sent a reference to the TRAI for framing a mechanism for using KYC based identification.[16] It would be advisable if the TRAI in its response also takes into account the competing rights involved in this issue of caller identification and suggests a framework that addresses these concerns as well.

Retaining anonymity on the internet: Individuals may choose to remain anonymous online for a number of reasons. This includes employees expressing opinions about their employers and whistleblowers, people providing anonymous tips to newspapers or law enforcement, people expressing political opinions and criticism that may be subject to persecution, or simply someone saying something that they may be embarrassed about.[17] In India, in particular, an individual’s caste can be derived from their name, and they may choose to remain anonymous or adopt a pseudonym to escape centuries of stigma and discrimination that their communities have faced. Religious, gender and sexual minorities may also make this choice for similar reasons. The broad definition of telecommunication services in the bill places restrictions on anonymity online and severely degrades an individual’s ability to exercise their fundamental right to freedom of expression.

Right to privacy: The overly broad definition of “telecommunication services” and what constitutes a “message” also brings a number of digital services under the ambit of this bill. This can include email, instant messaging, social media services, and even payments and e-commerce transactions. Mandating identification of individuals as they navigate these services, which they require to go about their daily lives, creates an unprecedented potential for surveillance and abuse of personal information. To evaluate the legal validity of this infringement on privacy, we can utilise the necessity and proportionality tests put forth by the Puttaswamy Judgment. The explanatory note accompanying the bill states that the purpose of this provision is to “prevent cyber frauds”, establishing a legitimate aim for mandating identification. However, it fails to justify whether this is the least intrusive means necessary to achieve the stated aim. Law enforcement agencies have access to a wide variety of metadata, such as IP addresses, already collected by digital services today, which can be used to identify individuals committing cyber crimes. Furthermore, as the internet is a global network, bad actors can evade identification by routing their internet traffic through another country by using services such as Virtual Private Network (VPNs), proxies and onion routing. Well resourced actors can simply hire someone in another country to communicate on their behalf. The infringement upon the right to privacy by this provision is also disproportionate to the objective sought. By mandating storage of personally identifiable information that is not required for the operation of the wide range of services that fall under the ambit of this bill, it allows not only for state surveillance, but also creates the possibility of misuse by criminal actors and hostile states who may gain unlawful access to this information through data breaches. Overall, this provision can easily be circumvented by the bad actors it intends to catch, leaving us with a surveillance mechanism that is ripe for misuse against ordinary, law-abiding citizens.

Misunderstanding how the internet works: This draft bill assumes and propagates a centralised view of the internet. Unlike traditional telecommunication services, which require access to a finite spectrum or other physical infrastructure, the internet allows any individual or organisation to self-host their own communication service. Several organisations and technologically savvy individuals host their own email services, instant messaging services, blogs and social media networks. It is unclear how the licensing provisions in this bill apply to people developing and hosting their own communication equipment.

Recommendation : Clause 4(8) should be deleted.

Clause 5. Spectrum Management

➔ 5(2)(b): “administrative process for governmental functions or purposes in view of public interest or necessity as provided in Schedule 1; or”

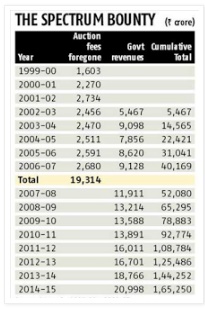

Comment: Even though the draft bill seeks to provide an explicit statutory framework and predictability for spectrum management policy in India, it appears that for the large part it would be relying on spectrum auctions for assignment of spectrum. While the bill provides for administrative allocation of spectrum for governmental functions or purposes in view of public interest or necessity as provided in Schedule 1, the explanatory note provided for the draft bill indicates auction to be the predominant method for spectrum assignment. Even though the explanatory memorandum cannot be used for legal interpretation, it can be used to indicate that for the foreseeable future the government intends to allocate spectrum predominantly through auctions. While it can be argued that an auction based regime ensures transparency, it also creates significant barriers to entry for smaller operators. It is also pertinent to mention that in the seven auctions held since 2010, the government has successfully sold 100 percent of the auction only once. Relying solely on auctions since 2010 has led to unsold spectrum, lost revenue, and deferring of the rural digital ecosystem.[18] Therefore, auctions should be supplemented with “administrative allocation” and other innovative approaches to ensure that affordable broadband connectivity does not remain within the remit of a few. For instance, Canada has initiated a consultation on a non-competitive local licensing framework in the 3900-3980 MHz Band and Portions of the 26, 28 and 38 GHz Bands, and one of its objectives is to facilitate broadband connectivity in rural areas.[19] Therefore, we would like to recommend the DoT to explore other forms of spectrum assignment and not rely solely on auctions to ensure efficient utilisation of available spectrum and to also ensure affordable access to hitherto underserved regions.

Moreover, the bill does not provide clarity with regard to unlicensed spectrum for public Wi-Fi, and assignment of shared spectrum for satcom services.[20] Spectrum allocation for satcom becomes all the more important as the draft bill seems to give a preference to auction for spectrum assignment, while the global practice on spectrum assignment for satcom has been administrative allocation.

Furthermore, clause 5(2)(b) read with Schedule 1 suggests that BSNL and MTNL can acquire spectrum through an administrative process in view of public interest or necessity. However, we would like to submit that spectrum assignment to BSNL and MTNL may no longer serve the public interest and it only protects a very small interest group. For context, BSNL and MTNL have a combined market share of only 9.83%, as per TRAI subscription data of Aug 31, 2022.[21] For such a small subscriber share, it cannot be argued that these PSUs serve a public interest. The government can easily migrate these subscribers to the other three telcos. Moreover, this also provides the PSUs with an unfair advantage over its competitors and distorts the level playing field, thereby creating competition concerns in the market.

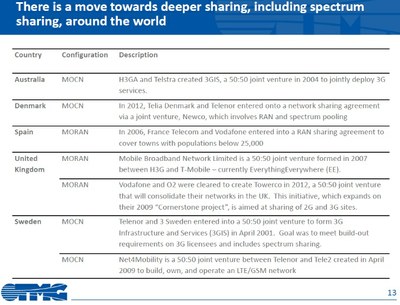

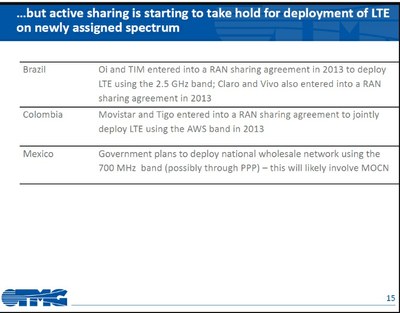

➔ 5(8): “The Central Government may, to promote optimal use of the available spectrum assign a particular part of a spectrum that has already been assigned to an entity (“primary assignee”), to one or more additional entity/ entities (“secondary assignees”), where such secondary assignment does not cause harmful interference in the use of the relevant part of the spectrum by the primary assignee, subject to the terms and conditions as may be prescribed.”

Comment: “Secondary assignment” of spectrum and the shift from “right to exclusive use” to “right to protection from interference”, as envisaged in 5(8) is a progressive move towards efficient utilisation of spectrum.

CIS, in its past submission[22] to the TRAI had highlighted the merits of a “use-or-share” approach in spectrum. The chasm that exists between expensive exclusive spectrum licensing and the licence-exempt ecosystem can be bridged by enshrining “use-it-or-share-it” provisions in spectrum licences. As such, ‘use-it-or-share-it’ rules enable the regulator to grant secondary access to licensed or governmental spectrum that is unused or underutilised.[23] ‘Use-it-or-share-it’ rules expand the productive use of spectrum without risking harmful interference or undermining the deployment plans of primary licensees. Clauses such as 5(8) enable “use-or-share” provisions are a step in the right direction.

➔ 5(9): “The Central Government, after providing a reasonable opportunity of being heard to the assignee concerned, if it determines that spectrum that has been assigned, has remained unutilized for insufficient reasons for a prescribed period, may terminate such assignment, or a part of such assignment, or prescribe further terms and conditions relating to spectrum utilization.”

Comment: There is lack of coherence between 5(8) and 5(9) when read together. 5(8) and 5(9) should be put as sub-clauses under a parent clause to ensure clarity.

We believe that the provision must be articulated clearly to state that licensees would first be given an opportunity to share spectrum and in cases where the entity fails to do so within a reasonable amount of time, the spectrum licence would be cancelled to prevent wilful spectrum hoarding. The Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA) in the 2nd Information Memorandum has expressed similar provisions with clarity. While, we feel five years may be an unnecessarily long timeframe for the government to enact spectrum sharing provisions, the language put forth by ICASA captures the essence of our argument:

“11.6.2 In cases where the spectrum is not fully utilised by the licensee within 5 years of issuance of the Radio Frequency Spectrum Licences, the Authority will initiate the process for the Licensee:

11.6.2.1 to share unused spectrum in all areas to ECNS licensees who may, inter alia, combine licensed spectrum in any innovative combinations in order to address local and rural connectivity in some municipalities including by entrepreneurial SMMEs;

11.6.2.2 to surrender the radio frequency spectrum licence or portion of the unused assigned spectrum in accordance with Radio Frequency Spectrum Regulations, 2015”

Recommendation: Clause 5(8) and 5(9) must be brought under one clause and it must be clarified that licence holders would lose their licence in case they fail to successfully incorporate spectrum sharing.

Clause 7. Breach of Terms and Conditions

➔ 7(1): “In case of breach of any of the terms and conditions of licence, registration, authorization or assignment granted under this Act, the Central Government may, after providing an opportunity of being heard to the party concerned, do any one or more of the following: ……”

Comment: Usually the consequences of breach are specifically illustrated in the licence. Listing the consequences of breach in the statute itself may lead to lack of clarity unless the terms of licence are also referenced. It could also be argued by a defaulting licensee that the powers listed in clause 7(1) are exhaustive and the Central Government cannot add any other conditions for breach of the conditions of the licence as in the licence agreement and any such conditions not specified in clause 7(1) are void and ultra vires the Statute.

Recommendation: In order to avoid such a situation, the clause should clearly state whether the powers listed in clause 7(1) are in addition to the terms and conditions that may be specified in the licence.

Chapter 4: Right of Way for Telecommunication Infrastructure |

Comment: The draft bill attempts to provide for a non-discriminatory and an affordable Right-of-way regime, which is appreciable. However, the provision suggests that the central government has an overriding power over the local government. Provided that the Constitution of India defines certain powers which reside with the local authority in terms of providing permissions in the local areas, it is unclear from the bill on how the coordination between various authorities will take place. We recommend that there needs to be a mechanism that ensures coordination between centre, state, and local authorities.

❖ 14(3) : “In the event the person under sub-clause (1) does not provide the right of way requested, and the Central Government determines that it is necessary to do so in the public interest, it may, either by itself or through any other authority designated by the Central Government for this purpose, proceed to acquire the right of way for enabling the facility provider to establish, operate, maintain such telecommunication infrastructure, in the manner as may be prescribed.”

Comment: The right of the Central Government to acquire the right of way should be in lieu of adequate and appropriate compensation to be paid to the property owner. This requirement should be clearly mentioned in sub-clause (3). The clause as it currently stands only mentions the Central Government’s right to acquire but contains no mention of said acquisition being in lieu of adequate and proportionate compensation.

Chapter 5. Restructuring, Defaults in Payment and Insolvency |

➔ 19(1): “Any licensee or registered entity may undertake any merger, demerger or acquisition, or other forms of restructuring, subject to provisions of applicable law, after providing notice to the Central Government of the same.”

Comment: Sub-clause (1) only requires that the Central Government be given a notice in case of merger, demerger, acquisition or restructuring of the licensee. Although sub-clause (2) requires that the successor entity shall comply with all the terms and conditions of the licence, considering the strategic nature of the telecommunications sector[24] it would be advisable to change the requirement of notice to a requirement of permission from the Central Government for restructuring the business rather than a mere notice requirement. In order for this requirement to not be a hindrance to the growth of the industry there could be a provision for deemed approval if the approval is not granted within a particular period of time.[25]

Recommendation: Any merger in the sector must be approved by the DoT. In order to ensure that this does not lead to unnecessary delays, a deemed approval route may be considered.

Chapter 6: Standards, Public Safety and National Security |

❖ 24(2): “On the occurrence of any public emergency or in the interest of the public safety, the Central Government or a State Government or any officer specially authorised in this behalf by the Central or a State Government, may, if satisfied that it is necessary or expedient to do so, in the interest of the sovereignty, integrity or security of India, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, or preventing incitement to an offence, for reasons to be recorded in writing, by order:

(a) direct that any message or class of messages, to or from any person or class of persons, or relating to any particular subject, brought for transmission by, or transmitted or received by any telecommunication services or telecommunication network, shall not be transmitted, or shall be intercepted or detained or disclosed to the officer mentioned in such order; or

(b) direct that communications or class of communications to or from any person or class of persons, or relating to any particular subject, transmitted or received by any telecommunication network shall be suspended”.

Comment: The pre-conditions for interception contained in the Bill are similar to those contained in the Telegraph Act, 1885, i.e. “occurrence of any public emergency or in the interest of the public safety, the Central Government or a State Government or any officer specially authorised in this behalf by the Central or a State Government, may, if satisfied that it is necessary or expedient to do so, in the interest of the sovereignty, integrity or security of India, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, or preventing incitement to an offence”. Although more stringent, these conditions are different from those contained in the Information Technology Act, 2000 which does not contain the added safeguard of there being a “public emergency or in the interest of public safety”.[26] With consumers spending more and more time on the internet and using internet based technologies and applications for communications, there is significant regulatory overlap between the Telecommunications Bill and the Information Technology Act, 2000. It is therefore advisable that the interception and blocking provisions under both the legislations should be aligned and standardised.

The judgement in the Puttaswamy case provides some guidance to assess the limits and scope of the constitutional right to privacy in the form of the three prong test. The test requires the existence of a law, a legitimate state interest and the restriction (to privacy) should be ‘proportionate'. The order to intercept, detain, disclose or suspend a communication made between private individuals, acts as a violation of privacy and to ensure that this does not provide extensive grounds to surveil people, the three prong test especially the grounds of proportionality combined with the necessity provision are essential to ensure that this provision is not used disproportionately.

More recently in Anuradha Bhasin vs Union Of India the Supreme Court stated “A public emergency usually would involve different stages and the authorities are required to have regards to the stage, before the power can be utilised under the aforesaid rules. The appropriate balancing of the factors differs, when considering the stages of emergency and accordingly, the authorities are required to triangulate the necessity of imposition of such restriction after satisfying the proportionality requirement.” The court while passing the judgement also stated “The concept of proportionality requires a restriction to be tailored in accordance with the territorial extent of the restriction, the stage of emergency, nature of urgency, duration of such restrictive measure and nature of such restriction. The triangulation of a restriction requires the consideration of appropriateness, necessity and the least restrictive measure before being imposed.”[27] The judgement while examining the duration of the suspension mentioned that any order which suspends the internet must adhere to the principle of proportionality and must not extend beyond necessary duration.

Recommendation: There is a need to look at the implications of such an order enabling blocking or suspension of services post the Puttaswamy judgement where informational privacy, and dignity were considered as some of the aspects of privacy. While this clause uses the test of necessity and expediency, we suggest that along with these two the clause also introduce the three prong test laid out in Puttaswamy I. In addition to this since this legislation has been drafted subsequent to the Anuradha Bhasin judgement the provisions of the legislation must be in conformity with the same in order to avoid confusion and reduce litigation.

Chapter 7: Telecommunication Development Fund |

➔ Clause 29: “The sums of money received towards the Telecommunication Development Fund under clause 27, shall first be credited to the Consolidated Fund of India, which shall be appropriated by the Central Government, in accordance with law made by the Parliament, to the Telecommunication Development Fund from time to time for being utilised to meet any or all of the following objectives:

(a) support universal service through promoting access to and delivery of telecommunication services in underserved rural, remote and urban areas;

(b) research and development of new telecommunication services, technologies, and products;

(c) support skill development and training in telecommunication;

(d) support pilot projects, consultancy assistance and advisory support towards provision of universal service under sub-clause (a) of this clause; and

(e) support introduction of new telecommunication services, technologies, and products.”

Comment: Clause 27 of the draft bill proposes to rename the Universal Service Obligation Fund (USOF) to Telecommunication Development Fund (TDF) and expand its scope to include underserved urban areas in addition to rural and remote areas. This has been done, ostensibly to expand the scope of current USOF to include within its ambit underserved urban areas, research and development, and skill development, among others.[28] While there is a need to spend the vast amount of unspent balance within the USOF, and spending it on skill development, investments in innovative low cost-technology that enables affordable broadband connectivity for all is important, the manner in which the TDF is currently defined is loose and vague. In order to ensure that the fund is spent to include digitally marginalised groups only, the purpose for which the TDF can be used needs to have an “exact” and “specific definition”. The purpose should be narrowly defined to include only those activities that have the potential to mitigate and bridge the many digital divides that exist in our country because in its absence TDF may be misused to subsidise urban middle class users as opposed to originally intended beneficiaries - the hitherto marginalised sections of the society.

Furthermore, the Bill suggests that the money received towards the TDF shall first be credited to the Consolidated Fund of India, which shall be appropriated by the Central Government, in accordance with law made by the Parliament. This is a relic of the erstwhile USOF policy funds, and allocations are made on a demand and review basis. One of the reasons that India has an unspent balance of nearly INR 50,000 crore in USOF is owing to a delay in its implementation due to bureaucratic delays since all credits to this fund require parliamentary approvals.[29] In order to ensure that funds received through USOF/TDF are utilised efficiently, the government must ring fence these funds and ensure that they are only spent on the objectives envisaged under the TDF. Furthermore, funds collected for this purpose must not be credited to the Consolidated Fund of India since requiring additional approvals delays implementation of the fund. For instance, the rural road fund is ring fenced which has ensured smoother flow of funds.[30] Moreover, auction proceeds, and other levies on the sector such as service tax and GST are already credited to the Consolidated Fund of India, therefore the government can afford to ring fence funds collected for universal service as opposed to crediting them to the Consolidated Fund of India.

Recommendation: The objectives for which the TDF can be utilised is vague and too broad and therefore the government would be well-advised to specify that TDF can only be utilised to ensure digital access, adoption and usage for digitally marginalised groups. This would go a long way in ensuring that the funds are not misspent on providing subsidies to users that may not be in need for such a subsidy. Furthermore, TDF must be ring fenced and not credited to the Consolidated Fund of India to ensure timely implementation.

Chapter 9: Protection of users |

➔ Clause 34 : “In the interest of the sovereignty, integrity or security of India, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, or preventing incitement to an offence, no user shall furnish any false particulars, suppress any material information or impersonate another person while establishing identity for availing telecommunication services.”

Comment: The intent behind this provision appears to be to prevent misrepresentation or identity and the giving of false information for availing telecom services. Whilst it is understandable that there may be privacy issues involved in the matter of revealing one’s identity for availing telecommunications services, the requirement to provide correct identity documents is a well established and accepted norm in the industry today which is manifest in the KYC requirements that have to be fulfilled by every customer. Therefore there is no need to qualify the obligation to provide true and accurate documents with the phrase “in the interest of the sovereignty, integrity or security of India, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, or preventing incitement to an offence”.

Chapter 10: Miscellaneous |

➔ Clause 46: Amendment to Act 24 of 1997

Comment: Clause 46 of the Bill significantly dilutes the power of TRAI and effectively renders the Regulator to the role of the government’s rubber stamp through proposed amendments to clause 11[31] of the TRAI Act. Section 11 of the TRAI Act as it currently stands requires DoT to solicit recommendations from TRAI on issues pertaining to licensing, new services, and spectrum management, where the powers vest with the government. However, if the Bill becomes a law, this would not be mandatory on the government’s part. It may or may not seek the Regulator’s recommendations, thus eroding the transparency which was built in the process of policymaking. Consequently, as per the current Bill, the government will effectively be the licensor, operator, and the Regulator. Since the government owns BSNL/MTNL (a telecom operator) the role of an independent regulator assumes even more significance. Even without the proposed amendments, the Indian regulator has been largely ineffective since it lacks significant functional autonomy including negligible penalisation powers, limited role in its hiring decisions, and lack of financial autonomy since it needs DoT’s approvals for its budget.[32] Even in its present form, TRAI has lesser power as compared to many regulators across the globe. For instance Federal Communications Commission (FCC) of the USA, Ofcom of the UK, and regulators in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka have powers over spectrum and licensing, while TRAI has only recommendatory powers.[33] With the advent of 5G, the lines between telecom and digital services are likely to blur even more and in order to ensure that we are able to exploit the vast potential this new wave of innovations could unleash, it is important to have skilled policymakers well-versed with technology at the helm of affairs. Amidst this backdrop, it is important to invest in enhancing TRAI’s competence by hiring subject matter experts, and ensuring that TRAI functions as an independent and transparent regulator.

Furthermore, the bill empowers the government to set up an alternate dispute resolution mechanism effectively making the role of Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal (TDSAT) redundant. Currently, TDSAT is the first body which looks into any dispute between two (i) telecom operators, (ii) telecom operators and the government, and (iii) between operators, the government and as well as the regulator. Only once the TDSAT has passed orders on such disputes can they be appealed in the Supreme Court. Therefore, clauses diluting the power of TRAI must be deleted. The government must also clarify what it means by an alternate dispute resolution mechanism, and the role it envisages for TDSAT.

Lastly, TRAI process is consultative by design providing various stakeholders with an opportunity to participate in the policymaking process. However, the proposed bill does not have any provisions mandating the DoT to hold transparent stakeholder consultations.

Recommendation: Clause 46 of the proposed bill should be deleted. Furthermore, the government must work towards further strengthening TRAI by hiring subject matter experts and further empowering TRAI by giving it penalising powers. Also, TRAI must be responsible for conducting spectrum audits and ensuring that licensees are adhering to licensing conditions.

➔ 46(k): “Provided further that the Authority may direct a licensee or class of licensees to abstain from predatory pricing that is harmful to the overall health of the telecommunication sector, competition, long term development and fair market mechanism” shall be inserted.”

Comment: The Bill through clause 46 (k) empowers the TRAI to decide on ‘predatory pricing’, which falls within the remit of the Competition Commission of India (CCI) which could potentially create jurisdictional overlaps between the two regulators. Even in the past, there has been friction between the two regulators on whether TRAI has jurisdiction to decide on matters relating to competition and predatory pricing in telecom tariffs.[34] In Competition Commission of India v. Bharti Airtel Limited & Ors[35], Supreme Court of India rejected the contention by the incumbent dominant operators (IDOs) that TRAI, as the sectoral regulator, had exclusive jurisdiction to rule on competition-related aspects in the industry. It ruled that if TRAI had determined that the IDOs had formed a cartel or colluded to block Jio’s entry, the CCI then would have jurisdiction to decide whether the IDOs’ actions had an appreciable adverse effect on competition. While TRAI’s powers of sanction were limited by the TRAI Act, the CCI had the power to prescribe and enforce structural remedies to promote genuine competition in the telecom sector. The court prescribed comity between TRAI and the CCI in the discharge of their roles.[36] Over time, the telecom sector has evolved from being a rudimentary voice service to being a complex data-centric converged service, and even though overlapping jurisdictions cannot be completely wished away,[37] there is a need for clearly defined roles for various ministries and regulators. And there will also be a need to adopt a consultative approach towards policymaking through inter-departmental consultations, an area that India has thus far been lacking in. As evidenced by the International Telecommunication Union’s (ITU) Global ICT Regulatory Outlook 2020, which ranks India at 94 (out of a total of 193) countries in terms of the maturity and collaborative approach shown by telecom regulatory bodies, lower than countries such as Japan, Singapore, Korea, Pakistan, Kenya, and Nigeria.[38]

Therefore, inserting such a provision may create more chaos and regulatory uncertainty. It is advisable that the government ensures there are no jurisdictional issues between the two regulators by clearly defining the role of TRAI and inserting provisions to facilitate inter regulatory consultation mechanism.

➔ Clause 48: “If the person committing an offence under this Act is a company, the employee(s) who at the time the offence was committed, was responsible to the company for the conduct of the business relating to the offence, shall be liable to be proceeded against and punished accordingly.”

Comment: While there is a need to ensure that offenders and violators of provisions under this Act are provided with penalties, there is a need to look at ways to ensure that the fear of penalties does not stifle innovation. This legislation intends to bring into its ambit a number of new stakeholders who might not be able to comply with all the requirements due to the inexperience, which could lead to inadvertent offences and violations. The current wording of clause 48, does not make any distinction between offences that were done with prior knowledge and malafide intentions and those done without knowledge of its commission.

Recommendation: We suggest that the Act keeps the wordings in line with similar legislations such as the draft Personal Data Protection Bill 2019. The revised text could have a proviso that reads as “Nothing contained in sub-clause (1) shall render any such person liable to any punishment provided in this Act, if he proves that the offence was committed without his knowledge or that he had exercised all due diligence to prevent the commission of such offence.”

Keeping in mind the existing burden of work both on the executive and the judiciary, and the time sensitive nature of the provisions of the Bill there is a need to look at different, swift, and inexpensive strategies. One possible way could be through Informal Guidances, similar to Security and Exchange Board of India (SEBI)’s Informal Guidance Scheme, which enables regulated entities to approach the Authority for non-binding advice on the position of law.[39] As there will be a number of new players that will be under the Bill, it would be useful for entities to get guidance. Another possible step could be to use Undertakings, where the regulator enforces the errant party to seek contractual undertakings to take certain remedial steps.[40]

➔ Clause 51: “Notwithstanding anything contained in any law for the time being in force, where the Central Government, a State Government or a Government of a Union Territory is satisfied that any information, document or record in possession or control of any licensee, registered entity or assignee relating to any telecommunication services, telecommunication network, telecommunication infrastructure or use of spectrum, availed of by any entity or consumer or subscriber is necessary to be furnished in relation to any pending or apprehended civil or criminal proceedings, an officer, specially authorised in writing by such Government in this behalf, shall direct such licensee, registered entity or assignee to furnish such information, document or record to him and the licensee, registered entity or assignee shall comply with the direction of such officer.”

Comment: The requirement to provide information or document even for “pending or apprehended civil or criminal proceedings” is too wide and could be misutilised, specially given the fact that there is no judicial authority making the determination that the information or document is required for such proceedings. Even in clause 91 of the Cr.P.C. , the requirement to provide documents or information is only for existing investigations, inquiries, trials or proceedings. Therefore the requirement to provide information, document or record for apprehended civil proceedings should be deleted.

Additional Comments |

➔ Comment: The bill fails to incorporate net neutrality requirements

Technological convergence and vertical integration within the sector make adherence to net neutrality critical to keep discrimination and anti-competitive conduct in check. While extant TRAI regulations, forbid TSPs from discriminating on the basis of content, sender or receiver, protocols or user equipment based on prior arrangements, by slowing down one application or providing fast lanes to another. However, there is lack of clarity on how adherence to net-neutrality principles is currently being monitored. In 2020, TRAI had recommended setting up a Multistakeholder body for monitoring adherence to net neutrality by licensees.[41] However, the draft bill fails to codify net neutrality requirements and as such non-discriminatory treatment of traffic does not find a mention in the bill or the explanatory note accompanying it.

Recommendation: The government must act on TRAI’s recommendations and set up the multistakeholder body to check adherence to net neutrality requirements by incorporating provisions to that effect.

➔ Comment: There is no provision in the bill that requires the government to report vital statistics and other information relating to the sector. We understand that both TRAI and DoT have taken efforts in publishing those statistics through DoT dashboard and reports such as the annual report, performance indicator reports, and subscriber reports. But, putting reporting requirements in the statute would be better.

Recommendation: In the interest of transparency and accountability, a clause requiring the government to report (quarterly or annually) vital statistics relating to the functioning and financial aspects of matters contained within the draft legislation. The reporting should also include the number of licences provided, licences revoked, number of blocking and suspension orders passed among others.

[1] “Response to TRAI consultation on Auction of Spectrum in frequency bands identified for IMT/5G”, Centre for Internet and Society, accessed 10 November 2022,https://cis-india.org/telecom/blog/response-to-trai-consultation-auction-of-spectrum-in-frequency-bands-identified-for-imt-5g

[2] “Response to TRAI Consultation Paper on Regulatory Framework for Over-The-Top (OTT) Communication Services”,Centre for Internet and Society, accessed 10 November 2022, https://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/response-to-trai-consultation-paper-on-regulatory-framework-for-over-the-top-ott-communication-services