Blog

Should Aadhaar be mandatory?

The article was published in Deccan Herald on December 9, 2017.

Getting their day in the court to hear interim matters is but a small victory in what has been a long and frustrating fight for the petitioners. In 2012, Justice K S Puttaswamy, a former Karnataka High Court judge, filed a petition before the Supreme Court questioning the validity of the Aadhaar project due its lack of legislative basis (the Aadhaar Act was passed by Parliament in 2016) and its transgressions on our fundamental rights.

Over time, a number of other petitions also made their way to the apex court challenging different aspects of the Aadhaar project. Since then, five different interim orders of the Supreme Court have stated that no person should suffer because they do not have an Aadhaar number.

Aadhaar, according to the Supreme Court, could not be made mandatory to avail benefits and services from government schemes. Further, the court has limited the use of Aadhaar to only specific schemes, namely LPG, PDS, MNREGA, National Social Assistance Program, the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojna and EPFO.

The then Attorney General, Mukul Rohatgi, in a hearing before the court in July 2015 stated that there is no constitutionally guaranteed right to privacy. But the judgement by the nine-judge bench earlier this year was an emphatic endorsement of the constitutional right to privacy.

In the course of a 547-page judgement, the bench affirmed the fundamental nature of the right to privacy, reading it into the values of dignity and liberty.

Yet months after the judgement, the Supreme Court has failed to hear arguments in the Aadhaar matter. The reference to a larger bench and subsequent deferrals have since delayed the entire matter, even as the government has moved to make Aadhaar mandatory for a number of government schemes.

At this point, up to 140 government services have made linking with Aadhaar mandatory to avail these services. Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra has promised a constitution bench this week, likely to look only into interim matters of stay on the deadline of Aadhaar-linking. It is likely that the hearings for the final arguments are still some months away. The refusal of the court to adjudicate on this issue has been extremely disappointing, and a grave disservice to the court's intended role as the champion of individual rights.

It is worth noting that the interim orders by the Supreme Court that no person should suffer because they do not have an Aadhaar number, and limiting its use only to specified schemes, still stand.

However, since the passage of the Aadhaar Act, which allows the use of Aadhaar by both private and public parties, permits making it mandatory for availing any benefits, subsidies and services funded by the Consolidated Fund of India, the spate of services for which Aadhaar has been made mandatory suggests that as per the government, the Aadhaar Act has, in effect, nullified the orders by the Supreme Court.

This was stated in so many words by Union Law Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad in the Rajya Sabha in April. This view is an erroneous one. While acts of Parliament can supersede previous judicial orders, they must do so either through an express statement in the objects of the Act, or implied when the two are mutually incompatible. In this case, the Aadhaar Act, while permitting the government authorities to make Aadhaar mandatory, does not impose a clear duty to do so.

Therefore, reading the orders and the legislation together leads one to the conclusion that all instances of Aadhaar being made mandatory under the Aadhaar Act are void.

The question may be more complicated for cases where Aadhaar has been made mandatory through other legislations, such as Prevention of Money Laundering Act, as they clearly mandate the linking of Aadhaar numbers, rather than merely allowing it. However, despite repeated appeals of the petitioners, the court has so far refused to engage with the question of the legality of such instances.

How may the issues finally be resolved? When the court deigns to hear final arguments, the Aadhaar case will be instructive in how the court defines the contours of the right to privacy. The right to privacy judgement, while instructive in its exposition of the different aspects of privacy, does not delve deeply into the question of what may be legitimate limitations on this right.

In one of the passages of the judgement, "ensuring that scarce public resources are not dissipated by the diversion of resources to persons who do not qualify as recipients" is mentioned as an example of a legitimate incursion into the right to privacy. However, it must be remembered that none of the opinions in the privacy judgement were majority judgements.

Therefore, in future cases, lawyers and judges must parse through the various opinions to arrive at an understanding of the majority opinion, supported by five or more judges. While the privacy judgement was a landmark one, its actual impact on the rights discourse and on matters like Aadhaar will depend extensively on the how the judges choose to interpret it.

It Hurts Them Too

Srinagar, J&K: For Mahender*, a member of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) posted in Srinagar for the last two years, the internet has been a way to feel virtually close to his children and wife in Bihar, nearly 1,900 kms away. After duty every day, he finds a quiet corner to start video-calling his wife. At the other end, she ensures their two children are beside her. “We discuss how our day went. Most of our conversations revolve around the kids, their schooling and food, and about my parents who live near our house,” says Mahender, who identified himself only with his first name.

However, Mahender and thousands of security personnel like him posted in the Kashmir Valley haven't found this easy connectivity always reliable, courtesy the government's frequent internet shutdowns, phone data connectivity cuts, and social media bans.

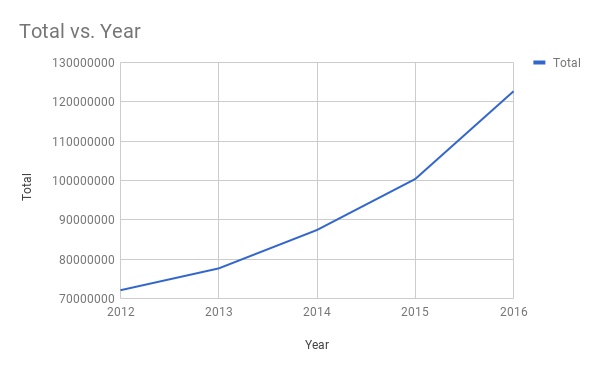

Jammu & Kashmir has faced 55 internet shutdowns between 2012 and 2017, as recorded by the Software Freedom Law Centre. The administration justifies this crackdown by citing "law-and-order situations" that occur during encounters of security forces with militants and, later, when protests and marches are carried out by civilians during militants' funerals.

Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani was killed by security forces and police on 8 July 2016, triggering a six-month-long “uprising” among civilians in Kashmir. Immediately after the shootout, security agencies shut the internet down. With 55 internet shutdowns in 2017 itself, it is something of a standard practice in Kashmir today to block social media or internet in a district or entire Valley each time there is an encounter. It is also a recurring practice of precaution against protests on Independence and Republic Day every year.

Security forces and police are not untouched by these shutdowns though. There are 47 CRPF battalions posted in the Kashmir region. “Our jawans experience difficulties during internet bans as they are not able to communicate with their families and friends as frequently as they do when internet is working,” says Srinagar-based CRPF Public Relations Officer Rajesh Yadav.

The J&K police, who are at the forefront of quelling protests and maintaining law & order in the Valley with a strength of nearly 100,000, also suffer. There have been growing instances of clashes between the Kashmiri police and protesters who believe their home force is being brutal during crowd control. The policemen have had to hide or operate in plain clothes. A senior police officer in Srinagar, who does not want to be named, says, “Our families are worried about our well-being when we are dealing with frequent agitations. In such a situation, when there is a ban, we find it difficult to stay in touch with our families.”

More dangerously, internet bans also hit the official communication of cops in action. Their offices are equipped with BSNL landline connections, which are rarely shut down, and they usually communicate through wireless; but for mobile internet most of them depend on private internet service providers, owing to their better connectivity, as the rest of the state. A senior police officer who deals with counter-insurgency in Kashmir speaks of the impact of cutting off phone data connectivity. "We have our own WhatsApp groups for quick official communication. We use broadband in offices only and can’t take it to sites of counter-insurgency operations.”

Yadav of the CRPF says, “While we have several effective means of communication for official purposes, social media is one that has accentuated our communication network. During internet bans, our work is not entirely hampered, but there is a little bit of pinch, since that speed and ease of working is not there.” Nevertheless, he defends the ban, insisting that Facebook and WhatsApp are handy tools for people to "flare up" the situation and "mobilise youths" during protests. "So, it becomes a compulsion for the administration to impose the ban."

Counter-insurgency forces have in the last few years created social media monitoring and surveillance cells. They say it is to equally match the extremists, including those in Pakistan, who use social media services like Telegram, Facebook and WhatsApp now, instead of their phones which can be tapped. It is also to keep an eye on suspected rumour-mongers and propagandists. For instance, 22-year-old Burhan Wani had gained the attention of security forces precisely because of the way he used his huge following, amassed through Facebook posts and gun-toting pictures, to inspire young Kashmiris to militancy.

“There is always monitoring and surveillance. If militants are using it, then they are within the loop,” says Yadav.

There is widespread public outrage against the state government and agencies who impose frequent net bans in Kashmir, but the CRPF official says it hampers their attempts to build an image and do public relations in Kashmir too. “We promote and highlight programmes like Civic Action and Sadhbhavana online, and that's not possible when there's no social media.”

"The public's criticism of the ban is justified,” the counter-insurgency official says. But they are compelled to use it in situations like during the recent scare around braid chopping, which was caused due to “rumour-mongering by persons with vested interests”. Kashmiri civil society had suggested that the police keep the internet up to issue online clarifications trashing the rumours, but it was not to be.

"The internet has made it possible to identify culprits while sitting in an office. But we have to shut it down in case of communal tensions which have the tendency to engulf the whole state,” says the senior cop. “When we have no option left, we go back to traditional human intelligence.”

Name changed to protect identity.

Mir Farhat is a journalist from Jammu & Kashmir, with an experience of reporting politics, conflict, environment, development and governance issues. His primary interests lie in reporting environment and development. He is a member of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.

Shutdown stories are the output of a collaboration between 101 Reporters and CIS with support from Facebook.

Digital Banking Dreams: Interrupted

Srinagar, J&K: Inside a buzzing branch of the Jammu & Kashmir Bank in Srinagar, 27-year-old Falak Akhtar is busy processing routine transactions. A member of the technical team, this young banker says that almost half of the branch's customers have registered their accounts with the M-Pay mobile app. However, the application built for convenience is not always dependable. As she attends to the rush of customers inside the branch, Falak reminds us that whenever there is an internet shutdown, the app is of no use. “The customers have to resort to traditional banking.” she says.

Every day, Falak’s branch executes 53% of its transactions online. “If the customers do online transactions, the cost per transaction for the bank is only Rs 7. But every time an internet ban is enforced in Kashmir, the cost of each transaction goes up to Rs 54,” she says.

Given that internet shutdowns in Kashmir are usually accompanied by an imposition of a physical curfew, simply going to the bank can be impossible. Ironically, it is during political tensions that Kashmiris, stuck indoors due to curfew or avoiding the streets to keep safe, need internet banking the most.

Zahid Maqbool, an information officer with the J&K government, uses the J&K Bank’s mobile app regularly to transfer money or do transactions. “But last year, when my brother studying outside the state needed money, I couldn’t use the app because of the internet ban,” he says. “During the tense situation and curfew, I took a huge risk to reach to the branch in Tral, where only two employees were present." It took him around three hours to transfer Rs 12,000 ($185) to his brother’s account "because the bank’s internet line was also running very slow”.

Showkat (name changed), manager of an ICICI Bank branch in Srinagar, says they use internet facilities of BSNL and Airtel during normal days. “Our branch has 20,000 customers, and around 40% of them use digital banking through an app called I-Mobile,” he says. Last year, as Kashmir plunged into a six-month-long political unrest after the killing of Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani on July 8, internet was snapped immediately and remained suspended for several months. The bank was not able to do online transactions throughout the summer. “And whenever there was a relaxation in curfew or strike, there used to be a huge rush of customers in the branch,” Showkat says.

“Whenever an internet ban is on in Kashmir, we suffer huge losses because we don’t manage to get new account holders,” says Showkat. “Since we run most of our operations online, the ban blocks the account holder from accessing the net and uploading scanned ID proofs.”

On an average, his branch opens 100 accounts per month. “But last year, amid the internet ban, we managed to open only 40 accounts in six months,” he says. For processing these account opening applications, the bank had to courier the forms to Chandigarh, the bank's nerve centre in North India. Account openings take 24 hours online, but here, the forms took six days to reach Chandigarh, after which it took another 8 days to process it.

To overcome hurdles faced during last year’s internet gag, the bank used the Indian Army’s VSAT network on lease. Showkat says such a line can be used for commercial purposes after clearance from the Army and a payment of Rs 15,000 per month. "Our ATMs were connected through that lease line," he says. "But the problem was that the gag had slowed down the VSAT as well.”

The slow-speed internet hampered cash withdrawals from ATMs, which created quite a furore. “The already frustrated customers started shouting that the bank employees were cheats, that we were irresponsible. It is very difficult to make them understand the technical aspects of it,” he says.

Although banks suffer during frequent internet gags, their plight is often overshadowed by the bigger political crisis in Kashmir. What's clear is that disrupted banking, fee payments, purchases and withdrawals, all severely cripple the everyday life of Kashmiris.

In 2016, angry customers, barred from e-banking due to internet clampdown, thronged banks after months, demanding they be given some respite on EMIs (monthly loan repayments) and other banking schemes. An official from the branch of a nationalised bank outside Srinagar says that when they refused to entertain such requests on procedural grounds, the customers entered into heated exchanges.

Showkat says that customers who had taken loans were neither able to repay the installments online, nor were they able to visit the branch because of unrest. “These customers then end up having to bear the high interest rate, and some of them had to face penalties.”

Mudasir Ahmad, the owner of a Kashmir Art Emporium in Central Kashmir’s Budgam, says that he had borrowed a loan of Rs 40 lakh ($62,400) from J&K Bank as capital for his handicraft business, but he had missed seven loan instalments last summer due to the internet clampdown. “I usually pay my loan installments through e-banking. Last year, when the internet was not working, I had to visit the bank to repay it. There are such long queues. It took me a whole day last year to pay one installment, which I otherwise pay within minutes through e-banking.”

Digital banking was introduced in Kashmir few years ago in an effort to reduce footfall in banks and increase online transactions. Online banking done through cards and apps was hailed as a step towards cashless economy. Abdul Rashid, a relationship executive of a State Bank of India branch in Srinagar, says, “But because of the internet gag at most times, we are not able to be a part of it."

Safeena Wani is an independent journalist from Kashmir. Her work has appeared in Al-Jazeera, Kashmir Reader and other regional publications. She is a member of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.

Shutdown stories are the output of a collaboration between 101 Reporters and CIS with support from Facebook.

Amid Unrest in the Valley, Students See a Dark Wall

Srinagar, J&K: On November 18, Srinagar lost 3G and 4G connectivity after a militant and a sub-inspector of the Jammu & Kashmir police force were killed, and one militant caught alive in a brief encounter on the outskirts of the city, near Zakoora crossing. District authorities said data connectivity was snapped to “maintain law and order”.

|  |  |  |

|---|

Students in Srinagar’s SPS Library. Picture Courtesy: Aakash Hassan

But to Jasif Ayoub, an aspiring chartered accountant, it seemed like an obstruction to his exam preparations. Not being able to access lectures and texts online, Ayoub was perturbed. He had moved from Anantnag in south Kashmir, to Srinagar, only to have an easy access to the vast pool of information on the world wide web. “My hometown witnesses internet shutdowns very frequently. That is why I moved to live with relatives in Srinagar to prepare for my exams. But the internet speed here too is getting worse by the day,” says Ayoub.

The internet is usually the first administrative casualty when any law & order situation arises in the Kashmir Valley, which has been restive and agitated over the last two decades. Despite the frequency of shutdowns, the state still does not issue a prior warning, or offer emergency connectivity measures. Residents know the pattern now: the mobile internet and SMS are the first to go down, and then broadband and other lease-line service providers follow.

J&K tops the list of Indian states that have witnessed most number of internet shutdowns, with 27 being the count from 2012 to 2017, according to internetshutdowns.in, run by Software Freedom Law Centre. There has been a sharp rise in the curbs on internet imposed this year, with over 30 shutdowns until November 22. Government authorities who issue and implement these bans say it is the only way to undercut the strength of social media in organising movements and resistance. The prime example is Burhan Wani, the 21-year-old Hizb-ul-Mujahideen commander who had used his Facebook account to popularise and justify militant resistance. Wani’s death saw protests erupting across the Valley, which made the state snap internet services for about six months on prepaid mobile networks. For four months, there was no internet access on postpaid mobile networks too. These have been the longest intervals of ban. However, day-long, hour-long and even week-long periods of non-connectivity are alarmingly common.

The incessant disruption of internet services prevents students from accessing online education resources. Class IX student Haiba Jaan in Srinagar depends on lectures from Khan Academy, an online coaching centre, to clarify a lot of concepts. A resident of Hyderpora in Srinagar, Haiba points to the i-Pad in her hand. “This is the best way of learning," she says. "I was not satisfied with my teachers in school or tuition classes. I found studying on the internet quite useful. But, the problem with that is the regular internet shutdowns." Her parents got a postpaid broadband connection the previous year to help Haiba. "But even that gives up many times during total internet shutdowns," says Haiba.

In May this year, the government suspended the use of 22 social media and messaging platforms in Kashmir for a month. Skype was one of the messaging services banned. This put Mehraj Din through great trouble. Shortlisted for a summer programme at Istanbul, Turkey, this scholar of Islamic Studies at Kashmir University, had to appear for the final interview via Skype. "The ban could have ended all my chances to get selected had the organisers not agreed to an audio interview considering the ground situation here," says Mehraj, who is currently compiling his dissertation for the university. "I have a deadline to meet, but repeated shutdowns have affected my work," he says. "This a punishment from the State."

Full libraries, half studies

When home and mobile internet connections are snapped, the state government's e-learning initiative in public libraries provides some respite. Mehrosha Rasool wants to secure an MBBS seat through the NEET competitive exam. She visits the SPS library in Srinagar religiously to access the study material that has been downloaded and made available on computers. The 17-year-old resident of Nishat in Srinagar says libraries are useful since one never knows how long the internet services at home will stay stable. Irshad Ahmad, another student utilising the facilities at SPS library, says he moved to Srinagar from Pattan town of north Kashmir because "this facility of accessing education material is not available at the library in my tehsil."

Most prominent libraries in Srinagar have computers and tablets for students’ access, "But the rooms often become overcrowded as hundreds of students have registered at the libraries for internet facilities," says Mehrosha.

Schools in the Valley, meanwhile, rely on traditional means in the absence of the e-learning systems. Javaid Ahmad Wani, a political science teacher from south Kashmir’s Anantnag, believes that with little time in the year to even complete the basic syllabus thanks to frequent and sudden school closures during periods of unrest, supplementary e-learning is a distant possibility. Even when teachers and students do have access to these resources to stay updated, internet shutdowns make them unreliable. Therefore, teachers and schools stick to conventional means. Javaid admits that he has himself lost opportunities to an internet shutdown. “I could not submit the form for the main exam of the J&K public service last year because there was no Internet,” he says.

Curbs pinch civil service aspirants

Many among the civil service aspirants are dependent on the internet for preparations. Anees Malik, a resident of Shopian, is preparing for the civil service exams. "I cannot afford coaching, so I rely on the internet," he says, especially for mock exams and previous question papers. "In such a situation, losing connectivity almost every other week is the worst thing to happen.”

Sakib Wani, a Kupwara resident who is currently studying chemistry in Uttarakhand, notices a marked indifference in Kashmir to using online resources. "Those applying for scholarships and pursuing higher education may be using it but not to the extent that students in other states of India do it,” Sakib says. He believes that the repeated internet ban could be a possible reason for students to not opt for online educational resources. With colleges and schools shut for weeks during conflict periods, the internet could have been a great way to continue education formally and personally, but the repeated shutdowns have closed that door of opportunity too.

Aakash Hassan is a Srinagar-based freelance writer and a member of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters. He has reported on conflict, environment, health and other issues for different publications across India.

Shutdown stories are the output of a collaboration between 101 Reporters and CIS with support from Facebook.

Online or Offline, Protest Goes On

Srinagar, J&K: Ahead of the Srinagar parliamentary by-polls held on 9 April 2017, the Jammu & Kashmir state government suspended mobile data services to prevent protests around the election. The constituency went to polls with strict restrictions on movement, and with no access to mobile internet. As soon as the electoral staff reached their respective polling booths, however, there were protests. People at dozens of locations in central Kashmir’s Budgam district began to gather to demonstrate against the central and state governments, which they believed had not safeguarded Kashmiri interests.

Faizan, a 12-year-old schoolboy, was killed in the Dalwan shooting |

Abbas, 21, was one of the victims of the shooting in Dalwan |

Abbas’ home in Dalwan |

The school in Dalwan where the shooting occurred |

Picture Courtesy: Junaid Nabi Bazaz

In Dalwan village, a picture-postcard village atop a hill 35 kms from Budgam town, no votes were cast: the officers fled the polling station, and the paramilitary forces and police shot at protesters. Two people – a 21-year-old son of a policeman and a 12-year-old schoolboy – died on the spot.

People of Dalwan have been voting in droves in every parliamentary, legislative and local body election, even on occasions where much of Kashmir boycotted polls. But in April, residents said they were fed up with legislators not working to ensure uninterrupted power, water supply, concrete roads, or even a permanent doctor at its only dispensary. So, a village that has never demonstrated or produced any militants in the last 30 years of uprisings in the Kashmir Valley erupted in protest that election day. Now, the cemetery in which the two killed civilians are buried has been renamed as Martyr’s Graveyard.

Bazil Ahmad, a resident of Dalwan, says that nothing could have prevented the protests that day. “We protested against state, it was a spontaneous response,” says 22-year-old Ahmad who threw his first stones that day. “If the government believes that an internet blockade could prevent protests, they’re living in a fool’s paradise.” He sees the internet only as a free platform to express his anger and disappointment. “The actual trigger for the anger comes from the denial of rights and state aggression, not because of the internet,” says Ahmad.

As the news about the killings spread to neighbouring villages word-of-mouth, residents there too protested. Journalists in these villages updated their newsrooms. In a few days, all newspapers in Kashmir carried the news of eight deaths, scores of injuries, and the appalling 6.5% voter turnout in Budgam and Ganderbal districts.

After the ban was lifted, videos captured on polling day were posted on Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp. One of them was a video of Farooq Dar, a voter returning from the polling booth, tied to the front bumper of a military vehicle as it patrolled villages. A paper with his name was tied to his chest, and a soldier announced on the loudspeaker, “Look at the fate of the stonepelter.” The video created an uproar internationally. The armed forces were accused of using a civilian as “a human shield”, pushing it to hold an inquiry, and the police to lodge an FIR.

After these videos emerged, the government on April 26 officially banned 22 social media sites and apps, including Facebook, WhatsApp and Twitter, for over a month. Once again, it seemed to have little effect on the protests – and protestors.

Sajad, who has been throwing stones for the past eight years at the armed forces, says, “The government is miscalculating the use of internet and the occurrence of protests.” The 28-year-old refers to the protests using the Kashmiri phrase kani jung, loosely translated as ‘stone battle’, which to him conveys a revolutionary zeal. Youths like Sajad who participate in the protests insist that they are provoked each time by an instance of human rights violation that exacerbates the long experience of militarisation, aspiration for “azadi”, and conflict in Kashmir. Internet shutdowns do nothing to erase this trigger, he says, and sometimes heighten their anger.

In just 2017, there have been 27 internet or social media bans in J&K, according to internetshutdowns.in. In the absence of evidence or study about its effects, it’s unclear if these blockades curb the spread of misinformation at all, or prevent the mobilisation of people for protests. For instance, on 15 April 2017, students from Degree College in south Kashmir’s Pulwama district protested against the armed forces for firing teargas and beating them. Though there was an internet ban in place, the incident went live on Facebook. It led to more student protests across the state. Schools, colleges and universities had to be closed for weeks.

Due to the frequency of blockades, several Kashmiris, including ministers, bureaucrats, civilians, protesters and police officers, have found a way out: they have turned to VPNs (Virtual Private Networks).

A VPN allows users to remain secure online and also enables them to access content or websites that are otherwise blocked. Sajad says, "A selective ban on the internet does not help, because we use VPNs. A person gains access to a network, and everyone in the area finds out how. Let the government block everything, it won’t stop protests.” To illustrate his point, Sajad gives the example of uprisings in the summer of 2016, during which internet, pre-paid and post-paid connections were shut for months. “Were there not protests?” he asks. “Kashmir was resisting Indian forces even before the internet existed, so why would it be difficult for us to use the same means now?”

Gulzar, a 30-year-old who has joined protests since he was 15, says the internet is more often used to disseminate information about the injustice, and not to organise protests. “A guy from Srinagar will only protest in Srinagar, and not go to other places. So, it is not too difficult to find out where protests are going on,” says Gulzar.

A DSP-rank police officer in the cyber crime cell of the J&K Police, on the condition of anonymity, says that bans have not yielded absolute results, but have been useful in preventing small-scale protests. He cited the example of district-level territorial internet blockades, done during gunfights between militants and the armed forces, to prevent immediate information sharing that may lead to the operation being compromised. “Say some militants are caught during an encounter in a village in Pulwama district. We block the internet as a precautionary measure in that area,” he says. “In case the district is violence-free, we reduce the bandwidth. That has now become the standard operating procedure.”

The police officer adds that accustomed to the bans, people now record the protests and later post videos on social media once the ban is lifted. “So, in effect, what the internet ban achieved is neutralised as soon as the internet is back on,” he says.

Names changed to protect identity.

Junaid Nabi Bazaz is a Srinagar-based journalist and a member of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters. He has been working as a journalist in Kashmir since 2010. He has covered human rights, economy, administration, crime and health over these years. He has also written for contributoria.com, an independent division of The Guardian.

Shutdown stories are the output of a collaboration between 101 Reporters and CIS with support from Facebook.

Business Woes from Saharanpur's Internet Ban

Saharanpur: The violence between groups of Thakurs and Dalits that engulfed Saharanpur district in Uttar Pradesh between April and June 2017 continues to haunt its residents. The UP administration had ordered an internet shutdown for 10 days, reportedly to prevent the spread of rumours that had erupted after another caste clash on May 23 in Shabbirpur.

Those running businesses in Saharanpur say they were affected in unexpected ways. They struggled to make regular transactions and incurred losses they haven't yet recovered from.

Forty-eight-year-old Rajkumar Jatav has been manufacturing ladies' shoes for 25 years in Saharanpur town. Helped by his sons Sushant and Rajkkumar, he runs a small-scale factory which employs 15 workers who make flat slippers, sandals, heeled shoes and joothis for the local market. Jatav says he suffered a loss of about Rs 1.25 lakh ($2000) during the 10-day internet shutdown.

"I did not get raw materials like paste solutions, synthetic leather, heels and sequins from my suppliers based in Kanpur and Agra when I failed to pay them the 50% advance through online transfer," says Jatav. "The situation outside the town was also tense. So there was no chance I could go or send someone to the banks either."

Jatav had started using the digital payment system only after demonetisation. "I started doing online payments after November 8, 2016, after I faced a lot of problems with cash availability during that time. Internet payments came as a boon for me and also for my suppliers," he says. But within six months of getting used to online transactions, Jatav faced this new hurdle: an internet shutdown. "To complete the shoe order, we have to invest from our pocket first, but when I couldn't, my suppliers refused to send me the material, which meant I could not complete a big order," he says. He calculates that the cancelled order cost him Rs 2 lakhs. In addition, a few of Jatav's reliable and talented shoe workers quit because he was unable to pay their wages on time.

Jatav's annual business turnover is around Rs 24 lakh (Rs 200,000 a month), and he gets his raw material from the markets of New Delhi, Bareilly and Agra. "I even tried to give my suppliers an account payee cheque but they declined it saying that it will take a lot of time to clear. I requested them again and again but to no use. For a supplier there are thousands of Rajkumar Jatavs. I am no special client to get the raw materials on credit," he says. Jatav admits that he is not prepared for another shutdown, and he would not be able to run his business if it happened again.

Many traders in Saharanpur city say narrate similar experiences. In May, a family business of trading edible oil wholesale saw its most unfamiliar financial challenge yet. It had been only three years since Shailendra Bhushan Gupta had taken over his elder brother's 26-year-old store. Gupta started to expand and diversify too, by launching an agency to trade the Fortune brand of oils. He employs five people, and his monthly turnover ranges between Rs 30-40 lakhs ($46,600-62,200). The 40-year-old also modernised some of the business practices, shifting much of the payments to suppliers online, for speed and ease of use.

During the internet shutdown in Saharanpur, Gupta did not expect to be affected, given the stability of his store and the large sale volume of his agency. But unexpectedly, his supplying company cancelled his order of 1000 litres of oil when he could not make the payment. "As per the agreement, I have to deposit at least 50% of the order amount in advance, and the rest of the payment is made when the oil is delivered to us. But during those 10 days, I could not make payment through any means, and my order was declined by the supplying company," he says. Gupta also tried to make the payment through RTGS but couldn't do that. The oil trader says that he ended up suffering a jolt of Rs 18 lakhs ($28,000).

Gupta is slowly trying to make up for the monetary loss and credit worthiness with his suppliers. "How can an internet shutdown be a solution for anything?" he asks. "I seriously don't know what to do if it happens again."

A property dealer in same central market faced a direct hit during the internet ban. Ashok Pundeer, who has been selling and renting commercial and residential properties for the past five years, estimates that he suffered a loss of Rs 22 lakhs ($34,200) during the internet shutdown as he could not get many properties registered in that period. "I had to return the token money to many buyers because there was no internet," he says. "All of us know that registry (property) and documentation is now done online in Uttar Pradesh. The clients were new and they refused to take the deal forward."

A property dealer is not easily trusted, admits Pundeer. This means he is paid only after the deal is done, and a lot of word-of-mouth business depends on his image and credibility. Every lost client is a potential loss of more. "It's not just me, but many dealers have incurred huge losses due to shutdown," says Pundeer. "Koi ration ki dukaan to hai nahi property dealing. Jo kuch hona hai online hi hona hai. Ab kya batayein, dekha jayega jo hona hoga," he throws his hand up in frustration, saying the real estate business is no grocery shop, and if there's no access to online transactions, then very little can be done.

Trying to keep an optimistic outlook, Pundeer says, "Jitna kuan khodo, utna paani milega". For his business to recover, he will have to double down with more focus and effort.

(With inputs from Saurabh Sharma)

Mahesh Kumar Shiva is a Saharanpur-based journalist and a member of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters. has been reporting for 23 years on crime, healthcare, society, politics, culture, sports, agriculture and tourism in his city. He has previously worked with publications like Dainik Janwani, Dainik Jagran, Amar Ujala, Ajit Samachar and more.

Shutdown stories are the output of a collaboration between 101 Reporters and CIS with support from Facebook.

Video

Rajkumar Jatav talks about the challenges his shoe manufacturing business faced during the shutdown. Video Courtesy: Mahesh Kumar Shiva

Internet and the Police: Tool to Some, Trash to Others

Panchkula, Haryana: Suspension of internet facilities to “prevent mishaps” has been a frequent exercise in Haryana during various agitations, but probing its effect on those responsible to maintain the law & order in the state shows a gap in acceptance of the information tool. There are some who understand its importance in bridging human interaction, and then, there are others who consider it nothing but an easy way to watch porn.

The tricity of Chandigarh, Panchkula and Mohali witnessed chaos and violence when Dera Sacha Sauda (DSS) chief Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh was convicted in two rape cases on August 25. Mobile internet services were shut down across Punjab, Haryana and Chandigarh for 72 hours as over one lakh followers of the much-revered “godman” started pouring into Panchkula, camping around the district court complex where the special CBI court was hearing the case. The ban was later extended for another 48 hours to last till August 29.

Reports claimed that 38 people died in the interim violence between August 25 and 29. The internet shutdown, evidently, didn’t serve the purpose. But it did affect the efficiency of the mechanism put in place to control the law and order situation.

Shutdowns obstruct us too: Cops

Panchkula police commissioner Arshinder Singh Chawla said they faced challenges in ascertaining size of the crowd gathering at various locations after the mobile internet communication was temporarily killed. “We were until then sharing information and photos on WhatsApp to figure out the number of people pouring in the city from various points as it helped identify problem areas. DSS followers had started gathering August 22 onwards,” said Chawla, who was heading the operations when DSS followers went on a rampage in Panchkula.

Unavailability of internet had hindered police operations during the Jat agitation in 2016 as well. Jagdish Sharma, a retired DSP who was part of the team countering agitators at the Munak canal when they targeted the chief source of Delhi’s water supply, said his team faced challenges in gathering strength due to the absence of mobile communication. “The protesters had a much larger count than our personnel at the canal, but they weren’t aware of this. We were fearful that our wireless messages asking for reinforcements may be tapped into by them. We could have easily conveyed the message if WhatsApp was working then,” said Sharma. The cops retained control over Munak canal by remaining at their position for two days, until the reinforcements arrived, while posing as if they were prepared to take on the Jat agitators, Sharma added.

The Panchkula police commissioner said that the drone they were using to take photographs and videos during the DSS violence also fell out of use once mobile internet was curtailed. With drones in operation, their tasks would have been much easier, Chawla said.

Panchkula deputy commissioner Gauri Parashar Joshi faced the brunt when her security staff could not communicate with the security personnel at the district court complex. SP Krishan Murari, who was heading a commando squad on the day, said they had to help Joshi scale a wall to escape the court complex as they could not ascertain a safe escape route. The DSS supporters had surrounded the entrances to the complex and were ready to clash with police authorities, he said. Joshi said she could not reach out to her colleagues in the administration to share important messages and orders as the mobile internet services didn’t work.

‘Ban can’t always be boon’

Ram Singh Bishnoi, who was cyber security in-charge with the Haryana police until January 2017, believes a medium like internet should not be broken down. “I agree that rumours spread like wildfire, but the government should devise other ways to counter the problem than imposing a ban on net services,” he said.

IG (Telecommunication) Paramjit Singh Ahlawat, however, said there is not much use of the internet when the situation turns volatile in the region. Things like internet don’t matter to people when their lives and property are in danger; these services are enjoyed when law and order is under control, he said.

The cops in Haryana, where internet has been shut down over 11 times in the past two years, may find some learning in the way former Mumbai police commissioner Rakesh Maria avoided a scuffle from turning into a communal riot. Maria was lauded for using WhatsApp and SMS service to convince people not to believe rumours being circulated on their phones when clashes broke out between two communities in Lalbaug during Eid celebrations in early 2015.

Former Haryana DGP Mahender Singh Malik does not believe a ban on internet prevents any untoward incident. Government authorities take such a step in the name of maintaining law and order, but the real reason behind clamping internet is to avoid the masses from being aware of the blunders committed by the same authorities, alleged Malik, terming the decision to ban internet as “unwise” and “against the digital India” initiative of the Centre.

Malik also suggested that people should get compensation when internet shutdown is forced on them.

‘Internet is for the jobless’

However, not all officials in the police department seem to agree with the benefits of internet.

SP (Telecommunication) Vinod Kumar of Haryana Police said: “How does it (internet) matter to a common man? Internet is for those who have no serious job. It is for those who have time to kill on mobile phones, laptops and at cyber cafes.”

In nearby Uttar Pradesh as well, some cops were of the view that internet shutdown did not have much of an impact on their job or general administration. Sub-inspector Vijay Singh was posted in Saharanpur when internet was banned from May 24 for 10 days following caste clashes. “Internet band hone se farak sirf un logon ko pada jinhe din bhar keval mobile hee chalana hota hai. Kaam karne wala aadmi mobile aur internet par samay nahi bitata (Only those who have no work suffer because of internet ban. Those who have work in hand do not spend time on mobile and internet),” said Singh, who is now posted in Lucknow.

“Internet matlab kya - video, Facebook, blue film... aur kya? Agar itne bade gyani hai jinhe internet band hone se farak pada to wo yaha kya kar rahe hai, kahe nahi jakar ke IIT me admission le liye? (What does internet mean - videos, Facebook, porn films… what else? If you are so affected with internet being banned, why not go and study at IITs,” said Kaushlendra Pandey, another SI-rank policeman from Azamgarh district in UP.

The government of India, on the other hand, is campaigning to promote digital inclusion and accessibility across the country.

With additional inputs from Sat Singh and Saurabh Sharma, both members of 101Reporters.com

Manoj Kumar is a Chandigarh based freelance writer and a member of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters. He has reported on a wide range of civic issues over the past 12 years. He has written for Dainik Jagran, Dainik Bhaskar, Amar Ujala, Outlook, etc.

Shutdown stories are the output of a collaboration between 101 Reporters and CIS with support from Facebook.

How Media beat the Shutdown in Darjeeling

Darjeeling, West Bengal: The West Bengal government banned internet in the hills of north Bengal on June 18. The ban was lifted on September 25, one hundred days later. The precautionary “law and order measure”, introduced in the wake of violence following the breakout of a fresh stir for separate Gorkhaland state, was used as a virtual tool by the administration to bargain for peace with protesters in subsequent weeks. Quite naturally, it caused severe hardships to over one million people. Journalists covering the agitation were among the most severely affected.

“It was a first for me — reporting breaking stories from the ground and having to dictate the development on the phone to my office back in Delhi,” says Amrita Madhukalya, a senior reporter with the DNA newspaper. “The first story I broke after reaching Darjeeling was how the agitation had caused losses in excess of Rs 100 crore ($15.6 million) for the tea industry. I sent that story via a string of five SMSes to office before reading it out to one of our subeditors to ensure no discrepancies crept in.”

Sometimes even phone networks were down. “I have a friend who owns a shop in a small market complex near Chowk Bazaar,” says another senior print journalist from New Delhi. “On this one occasion when even SMSes were not going through, this friend helped me access data from a location that only he knew of. There were at least five to ten journalists from national newspapers looking for internet in Darjeeling in mid-July. He clearly didn’t want to attract their or the district magistrate’s attention.”

The clampdown on internet connectivity began a day after three people died of bullet injuries following clashes between pro-Gorkhaland protesters and the police in the heart of Darjeeling town on June 17. One policeman was feared killed. It later came to light that, having braved a near fatal blow from a khukuri, a traditional Gorkha blade, he was severely injured but alive.

By the evening, several videos of an underprepared but infuriated police force thrashing protesters began to circulate on social media. The state intelligence informed Kolkata that the protesters were planning to march around town with the bodies of the three victims the next afternoon and that the social media outcry against the use of force by police was turning increasingly vitriolic. Internet services were clamped early next morning.

As the Gorkhaland movement lingered on and the intensity of violence waned, data services continued to remain a casualty. Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee said the service would be resumed once normality was restored. As the cycle of news shifted to more compelling narratives and senior journalists from big cities returned from Darjeeling, the vacuum was filled by Facebook news pages run by young social media activists, like With You Darjeeling, Chautari24, North Bengal Today, North Bengal Express, etc.

“A blanket ban on internet since June 17th, 2017 was the biggest challenge we faced,” says Rinchu D Dukpa, who edits the very popular Darjeeling Chronicle, a Facebook news page with over 140,000 subscribers. “Imagine over two months of no internet. Getting word out on important news events from the region was such a challenge those days. In addition, countering distorted, biased and unverified news and narratives spewed by mainstream media and even social media platforms paid for by the state was almost impossible due to lack of internet.”

On several occasions, especially after clashes between locals and the police, rumours quoting death toll would surface. During one such clash in Sukna near Siliguri, one news channel claimed three people had died. It later turned out that there was no casualty. One more interesting rumour that did the rounds was the imposition of President's rule in Darjeeling. Much of it was fuelled by a lack of healthy flow of information. That there was an internet ban did not help.

The administration of another popular Facebook page run from Darjeeling, which has over 35,000 likes, was taken over by the administrator’s friends in the US. Requesting that his and his page’s name be kept secret, the administrator says he requested his friends in the US to scour content from website reports and e-paper versions of the relevant newspapers.

The ban was eventually lifted on September 25, just five days after the Mamata Banerjee government succeeded in weaning away rebel leader Binay Tamang from the Gorkha Janmukti Morcha, the party leading the agitation. Binay went on to be appointed as the chairman of a new board of administrators for Darjeeling hills.

“The ban may have been very severe but Darjeeling’s geography did offer respite at certain locations,” says Biswa Yonzon, a freelance journalist. “Those area that face the hills of neighbouring Sikkim, would receive internet signals. The connectivity wasn’t always great but it did the job for most local journalists reporting for papers such as The Statesman, The Telegraph and The Times of India.”

In fact the area just behind Darjeeling’s town square Chowrasta, which faces the towns of Jorethang and Namchi in South Sikkim, is now known as the Jio hill, after the Reliance 4G network. In Kalimpong, the misty Carmichael hill too is called by the same name.

Manish Adhikary is a Siliguri-based freelance writer and a member of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.

Shutdown stories are the output of a collaboration between 101 Reporters and CIS with support from Facebook.

Was there an Unofficial Internet Shutdown in BHU & NTPC?

Varanasi/ Rae Bareli: , Uttar Pradesh: During the student-led protests at Banaras Hindu University in September, anger over how the university handled a sexual harassment complaint was exacerbated by the police brutality that rained down the protesting female students. Amidst this chaos, many students inexplicably found that they unable to communicate with their parents and peers because they couldn’t connect online.

Shraddha Singh, a second-year fine arts student at BHU, had to walk three kilometres to reserve her train ticket home and couldn’t call her mother to talk about the injuries she sustained during the lathi-charge on September 23. The 21-year-old student said, “First, the police came into the hostel to beat us up. Then the internet was blocked. Neither was the hostel WiFi working, nor the mobile internet. Forget about booking tickets, we weren’t even able to make calls.” She felt this was a deliberate attempt to disrupt the protest by those who were “afraid” of where it would lead.

Worse still, the hostel warden had asked the girls to vacate their dorms immediately, and the students were cast into the streets without access to the Internet. Tanjim Haroom, a Bangladeshi political science student at the university, found herself stranded in Varanasi like many of her classmates. "I go home only once in a year but this time, I was forced to vacate the hostel and I could not get in touch with any of my relatives or family due to this sudden shutdown of internet and phone services. I was helpless in this city and just had some Rs 700 ($11) with me. I finally got shelter at the Mumukshu Ashram and was able to contact my family from their landline phone.”

Predictably, officials from the university insisted that there wasn’t any clampdown on the internet. The then vice-chancellor, Professor Girish Chandra Tripathi, when asked about this unofficial shutdown, said that there was none. "There could have been a network issue because the internet was working fine in our office. I cannot say what the students have alleged. Making allegations is very easy," he said over the phone to 101reporters. Varanasi district magistrate Yogeshwar Ram Mishra also denied that internet or phone services were suspended during the protests.

But a worrying number of first-person accounts do prove otherwise. According to Avinash Ojha, a first-year post-graduate student at the university, internet and phone services were restricted in the varsity campus soon after the lathi-charge on the students. They weren’t able to get online from the night of September 23 to 25.

The students had to go to Assi Ghat or other far-flung places to talk to their families and make travel arrangements out of the city. Ojha also suspected the hand of the university’s vice-chancellor behind this move.

Another case of suspected unofficial shutdown might have occurred on November 1, when a boiler explosion occurred at the National Thermal Power Corporation plant in Rae Bareili, that has since killed 34 people.

A senior officer of NTPC, on the condition of anonymity, told 101reporters that Reliance Jio was asked to cap their services in the area until things settled down. "I had heard my seniors discussing the need for this in order to avoid panic. There are a large number of Jio users here, so that specific service was asked to restrict its internet speed and calling facility for a while.”

Here too, there is evidence that the outage affected several people in the area. Amresh Singh, a property dealer hailing from Baiswara area of Rae Bareli was in Unchahar when the explosion occurred. He discovered that his phone network was not working. "There was no internet on my mobile phone after 4pm. I was able to access internet only after reaching Jagatpur, which is around 10 kilometres away from Unchahar," said Singh. “It felt like the phone lines were deliberately disrupted. I initially thought something was wrong with my phone, but the people with me were also not able to use their phones. Maybe the government quietly shut down the network to prevent panic.”

Mantu Baruah, a labourer from Jharkhand working at the NTPC, had a near-identical experience. His Jio network stopped working after 4pm that day, and he was unable to contact his family on WhatsApp to tell them that he was safe. "I tried many times, maybe over a hundred times, to send an image but it didn’t work. Jio network was down. Neither video calls nor phone calls were working. The authorities had made this happen so people outside wouldn’t know what was going on here.”

But Ruchi Ratna, AGM (HR) at NTPC’s North Zone office in Lucknow, tells us that there was a network congestion that day, not a shutdown. "Even we were unable to talk to our officers and were getting our information through the media," she said. Sanjay Kumar Khatri, Rae Bareily's district magistrate said over the phone, "There is no question of an 'unofficial shutdown'. I myself faced issues in sending messages on WhatsApp but my BSNL mobile was working fine and even journalists here were sending images and videos real time.”

However, a senior communication manager at Reliance Jio's Vibhuti Khand office in Lucknow revealed to this reporter that the internet was indeed restricted in both these instances for 12 hours each. "This was only done on the order of the government. I do not hold any written information, but it must be with the head office," the communication manager said. At the time of publishing, our requests for comments from the official spokespeople of Jio had not received a response.

Arvind Kumar, principal secretary (Home), Uttar Pradesh government, said that there were no restrictions or shutdowns during either incident. "There could have been network issues. The government did not ask any service provider to restrict its services. I will look into the matter, about where the orders to restrict Jio were issued from, but it did not come from the Uttar Pradesh government," he said.

While activists have roundly criticised the Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services (Public Emergency of Public Safety) Rules, notified in August without public consultation, there is now a better-defined (albeit still vague) protocol for implementation of internet blackouts. For instance, only the central or state home secretary can issue the orders. Prior to this, internet restrictions were issued by various authorities, along with section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code, aimed at preventing “obstruction, annoyance or injury”. This wide berth has allowed the administration to quietly get away with short-term internet bans without proper explanation. In fact, those monitoring these shutdowns are only able to maintain such records by tracking media reports; no official records are available to the public. Without official transparency, often, if there is no news story, it is like there was no internet ban.

Saurabh Sharma is a Lucknow-based freelance writer and a member of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.

Shutdown stories are the output of a collaboration between 101 Reporters and CIS with support from Facebook.

Internet and Banking: A Trust Broken

Darjeeling, West Bengal: As the Internet shutdown in Darjeeling touched the notorious landmark of 100 days in late September, its impact was felt by members of Gorkha Janmukti Morcha (GJM) — the party agitating for a separate state of Gorkhaland. The state government’s move had managed to impair the communication and coordination among the agitators.

However, for most residents, lack of access to the internet meant months of crippled bank transactions and mounting financial strain. The impact of the move was felt by all sections of society and most services experienced a slowdown or complete paralysis.

Students from the town were among the worst hit as the internet ban cut off a steady flow of money from home for academic purposes.

“I had to cut down my daily meals to once a day to save whatever little currency notes I had, especially since it was not clear when the ban would be lifted,” said Shradha Subba, a resident of Darjeeling who is pursuing her Bachelors degree in Kolkata.

Her parents were not able to send her money due to the ban and arranging cash from another state was also not an option. “I had no option but to borrow money and even that was difficult as all my friends were from the hills and faced the same problem,” said Subba.

The parents of many students also felt hard done by the shutdown and said they often found it difficult to communicate with their children. Transferring money for their monthly educational needs was also impossible. “We were able to make phone-calls to our children once in a while, but we could not see them as video-calling was out of the question. We also could not send the money for their semester fees on time and had to ask our relatives in Sikkim to arrange cash for them,” said a concerned mother whose daughter was studying in Delhi.

The ban on mobile internet was imposed on June 18, 2017. Two days later, broadband service was also restricted. The initial shutdown was meant to last for only a week but it had since seen several extensions owing to non-cessation of agitations. Banks were left helpless especially in the face of uncertainty regarding when the restrictions would be lifted.

“None of the banking services were functional and no transactions were done during the period of internet shutdown. Even the ATMs were closed and people could not be provided normal service,” said Jagabandhu Mondal, district branch manager, State Bank of India.

People routinely missed bill payments and no online transactions were done during the course of the ban. Reports emerged of people travelling over 80 kilometres, either to Siliguri or to Sikkim, just to withdraw some money.

Those who had purchased new vehicles found themselves struggling to pay their monthly instalments despite having cash in their accounts. Travelling to Siliguri to pay the instalment was also daunting as the road transportation was restricted by agitating political parties and supporters picketing on the streets.

Santosh Rai, a resident who had purchased a car just before the internet ban, said: “I could not go to Siliguri or even pay online. Now I’m facing claims for penalty. It was very hard for the vehicle owners to pay the EMI for three months along with a penalty. I asked for help from my friends but how long will they pay.”

He claimed that several people were forced to default on payments due to the blanket ban imposed by the government. “We could have deposited the EMI but the banks were closed, and that is not our fault,” said Rai.

Another victim, Mukesh Rai, also echoed Santosh’s sentiments while describing how he had to default on EMI payments towards his new car. “I used to walk towards Melli, Rangpo, or Singtam (all small towns in Sikkim) to withdraw money as my family and I were in need of liquid cash. Even that became difficult mid-monsoon,” he said.

Experts also pointed out that the ban was enforced even as the rest of the country discussed Digital India and a push towards cashless economy.

Another resident, Pema Namgyal, said he had lost a job because of the ban on internet services. He had opted to work from home for an advertising agency based out of Bangalore. “I had taken up an editing and copywriting job with an advertising agency. I had an issue with my spine and since long leaves are not possible in creative agencies, I opted to work from home. Five days after I reached here, an indefinite strike was called and the internet was shut down. I couldn’t work as per my client’s schedule and when I could not coordinate with him, he looked for another copywriter and asked me to refund an advance payment he had made,” said Namgyal.

The manager of an HDFC bank branch, Paul Tshring Lepcha, said, “We use BSNL connections usually for banking work and once the network was down we had a hard time updating our system… there are alternative portals like Airtel and Vodafone but even that was of no use at the time,” recalls Lepcha,

Book size of private banks too saw a drop in these 100 days and the regulation regarding monthly maintenance of ₹5,000 in their customers’ accounts could not be continued. Officials from Indusland Bank said that people even started preferring government banks as they have a lower maintenance requirement. “During the ban period, no new account holders were registered and the mutual funds market also experienced a lull,” said an official from a private bank.

Roshan Gupta is a Siliguri-based journalist and a member of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.

Shutdown stories are the output of a collaboration between 101 Reporters and CIS with support from Facebook.

The Rising Stars in Music Loath Losing their Only Platform

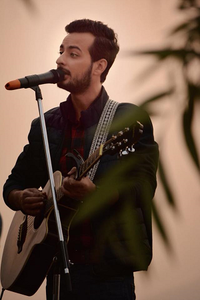

Srinagar, J&K: Amid the gaudy Old City area of Srinagar, where the air is heavy with the pungent smell of teargas shells, 25-year-old Ali Saifuddin has been busy working on compositions that he will perform at a prominent indie music festival in Pune in December 2017. Pune may be discovering Saifuddin’s music only now, but he has performed in Dubai and London too, owing to the fanbase he has garnered on social media.

|  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mehmeet Syed’s popularity on social media has taken her to countries like US, UK, Australia and Abu Dhabi (Picture Courtesy: Mehmeet Syed Facebook page) |

Umar Majeed shot to fame with his rendition of Pakistan’s national anthem on the Santoor | Yawar Abdal, a Kashmiri singer, says he doesn’t see the logic behind keeping the internet shut for months (Picture Courtesy: Yawar Abdal Facebook Page) |

|

It was in 2014 when the budding musician bought recording gear and created a Facebook page. Hours after uploading his first video, Saifuddin became an internet sensation. “I was stunned to see thousands of views on Facebook. People who I had never met with hailed my tunes and encouraged me to produce more,” Saifuddin says.

With 9,000 followers on Instagram and more than 6,000 ‘likes’ on his Facebook page, Saifuddin often gets offers to perform outside Kashmir.

“(As an artist) you need a platform, and in Kashmir, it is the internet that sides with you,” says Yawar Abdal, another popular Youtuber, whose song Tamanna has garnered over 400,000 views since June. “I uploaded a minute-long video on Facebook in April last year. It became viral and made me famous,” Abdal says.

The 23-year-old Pune University student has more than 13,000 followers on Instagram and above 10,000 likes on Facebook. “There are no shows organised in Kashmir. Internet is the only platform where people can broadcast what they posses,” he says.

Frequent curfews, even online, are like a curse for Kashmiris. Internet services are being clamped down in the Valley quite often, particularly after the killing of militant leader Burhan Wani on July 8. Wani’s killing sparked violent protests resulting in the deaths of 15 civilians the very next day. The clashes killed 383 people - including 145 civilians, 138 militants and 100 state and Central security personnel - and around 15,000 others were injured. While many were also put under illegal detention following the outbreak of deadly violence, the government suspended internet for more than six months in 2016.

In such a scenario, where shutdowns are stretching from streets to the social media, it is not surprising to see Kashmiris voice their dissent through art whenever they find a window open. In 2017, internet services were blocked 27 times across various districts of the Valley, either on mobile, or on both mobile and broadband, in the hope that it prevents rumour mongering and instigation of violence.

“This is unnatural and tantamount to choking a person’s right to free speech,” says Saifuddin, who has been criticising the human rights violations in Kashmir with songs that carry a political undertone. Son of medical doctors based in UK, Saifuddin got initiated to rock music through Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin during school days, before heading to Delhi University for a BA degree in 2011. “There I found the treasure of music. I finally had a computer and an internet connection. Youtube became my first, and so far, the only teacher,” recalls Saifuddin. His songs on Youtube include Aye Raah-e-Haq Ke Shaheedon, Phir Se Hum Ubharaygay, and Manzoor Nahi - a song he posted to protest against Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Kashmir in November 2015.

For Mehmeet Syed, whose music was limited to CDs since 2004, internet opened new avenues. Her popularity on social media has taken her to countries like US, UK, Australia and Abu Dhabi among others. “Being on social media is very important as it lets people stay updated about my work. My popularity touched new heights after I took to the internet,” says Syed, who owns a verified Facebook page with more than 1.20 lakh followers. On Instagram, she is a novice. But an internet ban means “heartbreak” to her. “Internet is not shut down in other places witnessing violence and conflict…We are very unfortunate to face internet bans,” says Syed.

“As singers, we have to record songs, mail them for editing, or receive content from studio. Without internet, we are stuck, paralysed,” she says.

Explaining how internet is more than a means of free expression, Mehmeet says, “Times have changed. This is the era of iTunes and YouTube. The songs we release in Kashmir are watched online across the globe. And this is how you earn today.”

The freedom to share content has empowered even the marginalised lot who were only known locally for their talent. Abdul Rashid, a transgender wedding singer popular as ‘Reshma’ in Srinagar’s Old City, became an online sensation after one of her wedding songs was widely viewed on Facebook, and media followed up with stories around her.

“Nobody knew me outside my locality. But today, I get calls from across Kashmir to sing on weddings. This became possible through Facebook. It gave me wide publicity,” Reshma says.

Umar Majeed, a Class 12 student from Zainakoot in Srinagar, is keeping the folk tradition of Kashmir alive with the help of internet. While the 19-year-old inherited skills on Santoor from his father, Abdul Majeed, it was social media that propelled him to fame. Umar played the national anthem of Pakistan on Santoor, accompanied by two other musicians on Rabaab. “The instrumental composition was viewed 450,000 times in two days,” says Umar, adding that they are working on a musical theme of the Indian national anthem as well.

With 5,000 friends on Facebooķ and 2,500 followers on Instagram, Umar has a quite wide network for a schoolkid. “We get a lot of encouragement and confidence when people comment on and appreciate our work online,” he says. But repeated internet ban keeps the young musician away from the much needed feedback.

“When I get an idea, I instantly compose it on Santoor and upload it on Facebook to get viewers’ response… But when there is internet ban, I have no mood to play even when I get an idea, and soon I forget it,” he says.

Mehmeet points out that internet not only promises freedom of expression but also provides monetary support to indie artists through platforms like iTunes, Google Play, Pandora, Amazon and Sawaan. She has been generating revenue to support her music through 21 of her tracks uploaded on these platforms, Mehmeet says.

The repeated shutdown of internet during the Republic Day and Independence Day also sends a wrong message to Kashmiris, says Mehmeet. “We realise that such attitude is step-motherly, which is unacceptable. And we as Kashmiris have not yet reached the stage where we think we have got independence.” Saifuddin seconds her sentiments. “If it is a democracy, then I have a right to speak my heart out. Why would the government choke my voice?” he asks.

When asked if the clamping down of internet service affects his music and earning, Saifuddin retorts poetically: “If not for the internet, I wouldn’t be around. So yes, it pains to see Kashmir being sealed on streets and on the cyberspace as well.

“It makes you angry at times to see things that happen nowhere but in Kashmir.”

Abdal, on the contrary, wants his music to be apolitical. “I sing the songs of Sufi saints and strive to rejuvenate the dying Kashmiri music,” he says.

But, the ban on internet services leaves him perturbed. “Without listeners, you begin losing interest. I hope one day the government understands that there is no logic in keeping the internet shut for weeks and months,” says Abdal, adding that he also observes a drop in demand for live gigs in the absence of internet.

“When you have a lot to share, but the medium through which you could take it to people is blocked, discomfort is what you’re left with.”

Umar Shah and Mir Farhat are Srinagar-based freelance writers and members of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.

Shutdown stories are the output of a collaboration between 101 Reporters and CIS with support from Facebook.

Stock Brokers Don't Love an Internet Shutdown

Ahmedabad, Gujarat: An internet shutdown means breaking contact with the lifeline of the stock market: information about share price movement. “The entire momentum for trading and investing comes from the control the trader feels he has on information about share prices," says Minesh Modi, a trader based in Ahmedabad. "The internet puts information on our fingertips, so the trader could play on the stock exchange. It gives you a sense of control on the data, and is also mechanism to trade."

So, when the Gujarat government shut the internet down for a week during the Patel agitation in September 2015, and for four hours to prevent cheating on phones during a Revenue Accountants Recruitment Exam in February 2016, Modi says, "That intense feeling of connect goes away, and the faith is shaken.”

An obvious fallout of mobile internet shutdown is that terminals connected via phone internet stop working, and mobile trade is not possible. However, many Gujarati investors say that while they check price variations and movements online, they still trade through brokerage houses. Playing the stock market is usually a part-time business activity for most Gujaratis. “I don’t trade online directly. I place actual orders of purchase/sell through my broker," says YK Gupta, an investor in the city. Still, he did struggle during the internet shutdown. “I couldn't keep a tab on the price movement, and had to call up my broker for updates. How many times can I take updates on the phone? The television gives prices of only a few stocks, and there is a delay of three to five minutes of prices on the television. Stock prices being as volatile as they are, that time gap can be life-changing in the stock market.” Not willing to risk a huge mistake, Gupta chose to stay away from making any stock transactions during internet shut down.

The stock market rides on people's aspirations and individual deductions about trends and data, which in turn impacts business valuations. Since internet penetration has increased, traders say there is a premium on speedy reaction as well. Anil Shah, a former director with the Bombay Stock Exchange (2011-14) and a member of the National Stock Exchange, believes that an internet shutdown, however partial, will paralyse the ecosystem that sustains the share market. “Most of our work is on the terminals and when they stop, the smooth flow gets disrupted. The information that is the base in the stock market, the actual trading and fund flow work, all this will stop. When the internet stops, data stops, and the flow of work stops. It's as simple as that,” he says.

Recalling the impact of the internet and how it has evolved and woven itself into the stock market ecosystem, Shah adds, “Earlier, when the telephone number was the basis of trading, we could establish connectivity via phones. But since 2006-7, we have slowly moved to the internet to establish interconnectivity. The more reliable, faster and cheaper the internet services got, the more it integrated itself into our trading patterns. More people shifted to it as a connecting platform. About 95% connections are now established online."

He says that NSE/BSE members now have a dedicated lease line so that they don’t lose contact with the stock market. "Many brokerage firms are connected via VSAT linkages, so that we, as Gujarat state, don’t get disconnected fully with the rest of India. The loss due to internet shutdown is not quantifiable. It will have to be measured as the cost of a missed opportunity."

It is not just the stocks, but also banking transactions that stop or decrease drastically in volume when the internet stops, Shah says. “During the Patidar agitation, mobile internet services in most areas were shut down. However, broadband services were not stopped, so the brokers managed to keep the ball rolling. But brokers will lose in volumes. It is difficult to put a figure to it, but the movement and momentum of trade goes down.”

Echoing a similar sentiment, VK Sharma, head of Public Consulting Group and Capital Market Strategy at HDFC Securities, says that large companies have the facility to call their other branch offices and get the transactions through. So only customers and traders who don’t have a landline fallback option will be affected. However, those who wish to transact on the stock market with help of mobiles will not be able to do so. “This way, the volume of transactions is not stopped completely, but definitely curtailed,” Sharma says. “The decrease can be roughly estimated to be around 3%, but the state-wise breakdown of transactions and impact is not available from the exchange. Moreover, internet slowdown or shutdown results in a lot of disputes among traders and brokers - about the price entered into for transaction and the price that the deal is finalised on.”

Sarit Choksi, an investor who trades regularly, lamented the absence of a recovery mechanism for the losses that the people incurred. “When the net shuts off, we have to call the broker, who does not have dedicated phone lines to handle the huge hike in calls, so getting through to him is itself a challenge,” he says. “Then, as we don’t have the information at our fingertips, we cannot adjust the mutual funds choice, ‘stop loss’ and set ‘buy or sell’ limits in tune with the market movement. By the time I see it on tv, and get through to the broker to execute the deal, the price has changed. Who is going to compensate for this loss?”

It’s impractical to tell the Stock Exchange Bureau of India or the traders that the transactions could not go through due to internet shutdown, or ask them to forgive the price difference due to the long waiting time on the telephone. If brokerage houses makes a mistake, Choksi explains, arbitration is available, but there is no platform to claim or address the kind of losses one incurs due to external limitations like an internet ban.

“If internet connectivity is put on ransom due to political ambitions, it is very disruptive,” Choksi says. “In a society deliberately being pushed to go digital, the impact of such a shutdown is felt in financial and social sectors. When such political decisions are taken without considering the other impacts, our bread and butter is affected, and we are left high and dry, with no recourse or means to compensate the loss.”

Binita Parikh is a Ahmedabad - based freelance writer and a member of 101Reporters.com, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.