Blog

Paper-thin Safeguards and Mass Surveillance in India

This need for better safeguards was made apparent when the Gujarat government illegally placed a young woman under surveillance for obviously illegitimate purposes, demonstrating that the current system is prone to egregious misuse. While the lack of proper safeguards is problematic even in the context of targeted surveillance, it threatens the health of our democracy in the context of mass surveillance. The proliferation of mass surveillance means that vast amounts of data are collected easily using information technology, and lie relatively unprotected.

This paper examines the right to privacy and surveillance in India, in an effort to highlight more clearly the problems that are likely to emerge with mass surveillance of communication by the Indian Government. It does this by teasing out Indian privacy rights jurisprudence and the concerns underpinning it, by considering its utility in the context of mass surveillance and then explaining the kind of harm that might result if mass surveillance continues unchecked.

The first part of this paper threads together the evolution of Indian constitutional principles on privacy in the context of communication surveillance as well as search and seizure. It covers discussions of privacy in the context of our fundamental rights by the draftspersons of our constitution, and then moves on to the ways in which the Supreme Court of India has been reading the right to privacy into the constitution.

The second part of this paper discusses the difference between mass surveillance and targeted surveillance, and international human rights principles that attempt to mitigate the ill effects of mass surveillance.

The concluding part of the paper discusses mass surveillance in India, and makes a case for expanding our existing privacy safeguards to protect the right to privacy in a meaningful manner in face of state surveillance.

Paper-thin Safeguards and Mass Surveillance in India File

Chinmayi-Arun-Paper-thin-Safeguards-and-Mass-Surveillance-in-India.pdf

—

PDF document,

1224 kB (1254181 bytes)

Chinmayi-Arun-Paper-thin-Safeguards-and-Mass-Surveillance-in-India.pdf

—

PDF document,

1224 kB (1254181 bytes)

DesiSec: Cybersecurity and Civil Society in India

Originally the idea was to do 24 interviews with an array of international experts: Technical, political, policy, legal, and activist. The project was initiated at the University of Toronto and over time a possibility emerged. Why not shape these interviews into a documentary about cybersecurity and civil society? And why not focus on the world’s largest democracy, India? Whether in India or the rest of the world there are several issues that are fundamental to life online: Privacy, surveillance, anonymity and, free speech. DesiSec includes all of these, and it examines the legal frameworks that shape how India deals with these challenges.

From the time it was shot till the final edit there has only been one change in the juridical topography: the dreaded 66A of the IT Act has been struck down. Otherwise, all else is in tact. DesiSec was produced by Purba Sarkar, shot and edited by Aaron Joseph, and directed by Oxblood Ruffin. It took our team from Bangalore to Delhi and, Dharamsala. We had the honour of interviewing: Malavika Jayaram, Nitin Pai, Namita Malhotra, Saikat Datta, Nishant Shah, Lawrence Liang, Anja Kovacs, Sikyong Lobsang Sangay and, Ravi Sharada Prasad. Everyone brought something special to the discussion and we are grateful for their insights. Also, we are particularly pleased to include the music of Charanjit Singh for the intro/outro of DesiSec. Mr. Singh is the inventor of acid house music, predating the Wikipedia entry for that category by five years. Someone should correct that.

DesiSec is released under the Creative Commons License Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC by 3.0). You can watch it on Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/123722680 or download it legally and free of charge via torrent. Feel free to show, remix, and share with your friends. And let us know what you think!

Video

IANA Transition Stewardship & ICANN Accountability (II)

The discussions and the processes established for transition plan have moved rapidly, though not fast enough—given the complicated legal and technical undertaking it is. ICG will be considering the submitted proposals and moving forward on consultations and recommendations for pending proposals. ICANN53 saw a lot of discussion on the implementation of the proposals from the numbers and protocols community, while the CWG addressed the questions related to the 2nd draft of the names community proposal. The Protocol Parameters (IANA PLAN Working Group) submitted to ICG on 6 January 2015, while the Numbering Resources (CRISP Team) submitted on 15 January 2015. The Domain Names (CWG-Stewardship) submitted its second draft to ICG on 25 June 2015. The ICG had a face-to-face meeting in Buenos Aires and their proposal to transition the stewardship of the IANA functions is expected to be out for public comment July 31 to September 8, 2015. Parallelly, the CCWG on Enhancing ICANN Accountability offered its first set of proposals for public comment in June 2015 and organised two working sessions at ICANN'53. More recently, the CCWG met in Paris focusing on the proposed community empowerment mechanisms, emerging concerns and progress on issues so far.

Number and Protocols Proposals

The numbering and the protocol communities have developed and approved their plans for the transition. Both communities are proposing a direct contractual relationship with ICANN, in which they have the ability to end the contract on their terms. The termination clause has seen push back from ICANN and teams involved in the negotiations have revealed that ICANN has verbally represented that they will reject any proposed agreement in which ICANN is not deemed the sole source prime contractor for IANA functions in perpetuity.[1] The emerging contentious negotiations on the issue of separability i.e., the ability to change to a different IANA functions operator, is an important issue.[2] As Milton Mueller points out, ICANN seems to be using these contract negotiations to undo the HYPERLINK "http://www.internetgovernance.org/2015/04/28/icann-wants-an-iana-functions-monopoly-and-its-willing-to-wreck-the-transition-process-to-get-it/#comment-40045"community process and that ICANN’s staff members are viewing themselves, rather than the formal IANA transition process shepherded by the ICG, as the final authority on the transition.[3] The attempts of ICANN Staff to influence or veto ideas regarding what solutions will be acceptable to NTIA and the Congress goes beyond its mandate to facilitate the transition dialogue. The ARIN meeting[4] and the process of updating MoU with IETF which mandates supplementary SLAs[5] are examples of ICANN leveraging its status as the incumbent IANA functions operator, with which all three operational communities must negotiate, to ensure that the outcome of the IANA transition process does not threaten its control.

Names Proposal

Recently, the CWG working on recommendations for the names related functions provided an improved 2nd draft of their earlier complex proposal which attempts to resolve the internal-external debate with a middle ground, with the creation of Post-Transition IANA (PTI). PTI a subsidiary/affiliate of the current contract-holder, ICANN, will be created and handed the IANA contract and its related technology and staff. Therefore, ICANN takes on the role of the contracting authority and PTI as the contracted party will perform the names-related IANA functions. Importantly, under the new proposal CWG has done away altogether with the requirement of “authorisation” to root zone changes and the reasons for this decision have not been provided. The proposal also calls for creation of a Customer Standing Committee (CSC) to continuously monitor the performance of IANA and creation a periodic review process, rooted in the community, with the ability to recommend ICANN relinquishing its role in names-related IANA functions, if necessary. A key concern area is the external oversight mechanism Multistakeholder Review Team– has been done away with. This is a significant departure from the version placed for public comment in December 2014. It is expected that clarification will be sought from the CWG on how it has factored in inputs from the first round of public comments.

Consensus around the CWG 2nd Draft

There is a growing consensus around the model proposed—the numbers community has commented on the proposal that it does "not foresee any incompatibility between the CWG's proposal”.[6] On the IANA PLAN list, members of the protocols community have also expressed willingness to accept the new arrangement to keep all the IANA functions together in PTI during the transition and view this as merely a reorganization.[7] However, acceptance of the proposal is pending till clarification related to how the PTI will be set up and its legal standing and scope are provided.

Structure of PTI

Presently, two corporate forms are being considered for the PTI, a nonprofit public benefit corporation (PBC) or a limited liability corporation (LLC), with a single member, ICANN, at its outset. Milton Mueller has advocated for the incorporation of PTI as a PBC rather than as a LLC, with its board composed of a mix of insiders and outsiders.[8] He is of the view that LLC form makes the implementation of PTI much more complex and risky as the CWG would need to debate mechanisms of control for the PTI as part of the transition process. The choice of structure is important as it will define the limitations and responsibilities that will be placed on the PTI Board—an important and necessary accountability mechanism.

Broadly, the division of views is around selection of the Board Members that is if they should be chosen either by IANA's customers or representative groups within ICANN or solely by the Board. The degree of autonomy which the PTI has given the existing ICANN structure is also a key developing question. Debate on autonomy of PTI are broadly centered around two distinct views of PTI being incorporated in a different country, to prevent ICANN from slowly subsuming the organization. The other view endorsed by ICANN states that a high degree of autonomy risks creates additional bureaucracy and process for no discernible improvement in actual services.

Functional Separability

Under the CWG-Stewardship draft proposal, ICANN would assume the role currently fulfilled by NTIA (overseeing the IANA function), while PTI would assume the role currently played by ICANN (the IANA functions operator). A divisive area here is that the goal of “functional separation” is defeated with PTI being structured as an “affiliate” wholly owned subsidiary, as it will be subject to management and policies of ICANN. From this view, while ICANN as the contracting party has the right of selecting future IANA functions operators, the legal and policy justification for this has not been provided. It is expected that ICANN'53 will see discussions around the PTI will focus on its composition, legal standing and applicability of the California law.

Richard Hill is of the view that the details of how PTI would be set up is critical for understanding whether or not there is "real" separation between ICANN and PTI leading to the conclusion of a meaningful contract in the sense of an agreement between two separate entities.[9] This functional separation and autonomy is granted by the combination of a legally binding contract, CSC oversight, periodic review and the possibility of non-renewal of the contract.[10]

Technical and policy roles - ICANN and PTI

The creation of PTI splits the technical and policy functions between ICANN and PTI. The ICANN Board comments on CWG HYPERLINK "http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-cwg-stewardship-draft-proposal-22apr15/pdfrIUO5F9nY4.pdf"PrHYPERLINK "http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-cwg-stewardship-draft-proposal-22apr15/pdfrIUO5F9nY4.pdf"oHYPERLINK "http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-cwg-stewardship-draft-proposal-22apr15/pdfrIUO5F9nY4.pdf"posal also confirm PTI having no policy role, nor it being intended to in the future, and that while it will have control of the budget amounts ceded to it by ICANN the funding of the PTI will be provided by ICANN as part of the ICANN budgeting process.[11] The comments from the Indian government on the proposal states this as an issue of concern, as it negates ICANN's present role as a merely technical coordination body. The concerns stem from placing ICANN in the role of the perpetual contracting authority for the IANA function makes ICANN the sole venue for decisions relating to naming policy as well as the entity with sole control over the PTI under the present wholly subsidiary entity.[12]

Key areas of work related to the distinction between the PTI and ICANN policy and technical functions include addressing how the new PFI Board would be structured, what its role would be, and what the legal construction between it and ICANN. The ICANN Board too has sought some important clarifications on its relationship as a parent body including areas where the PTI is separate from ICANN and areas where CWG sees shared services as being allowable (shared office space, HR, accounting, legal, payroll). It also sought clarification on the line of reporting, duties of the PTI Directors and alignment of PTI corporate governance with that of ICANN.

The Swedish government has commented that the next steps in this process would be clarification of the process for designing the PTI-IANA contract, a process to establish community consent before entering the contract, explicit mention of whom the contracting parties are and what their legal responsibilities would be in relation to it.[13]

Internal vs External Accountability

The ICANN Board, pushing for an internal model of full control of IANA Functions is of the view that a more independent PTI could somehow be "captured" and used to thwart the policies developed by ICANN. However, others have pointed out that under proposed structure PTI has strong ties to ICANN community that implements the policies developed by ICANN.[14] With no funding and no authority other than as a contractor of ICANN, if PTI is acting in a manner contrary to its contract it would be held in breach and could be replaced under the proposal.

Even so, as the Indian government has pointHYPERLINK "http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-cwg-stewardship-draft-proposal-22apr15/pdfJGK6yVohdU.pdf"edHYPERLINK "http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-cwg-stewardship-draft-proposal-22apr15/pdfJGK6yVohdU.pdf" out from the point of view of institutional architecture and accountability, this model is materially worse off than the status quo.[15]

The proposed PTI and ICANN relationship places complete reliance on internal accountability mechanisms within ICANN, which is not a prudent institutional design. The Indian government anticipates a situation where, in the event there is customer/ stakeholder dissatisfaction with ICANN’s role in naming policy development, there would be no mechanism to change the entity which fulfils this role. They feel that the earlier proposal for the creation of a Contract Co, a lightweight entity with the sole purpose of being the repository of contracting authority, and award contracts including the IANA Functions Contract provided a much more effective mechanism for external accountability. While the numbers and protocol communities have proposed a severable contractual relationship with ICANN for the performance of its SLAs no such mechanism exists with respect to ICANN's role in policy development for names.

Checks and Balances

Under the current proposal the Customer Standing Committee (CSC) has the role, of constantly reviewing the technical aspects of the naming function as performed by PTI. This, combined with the proposed periodic IANA Function Review (IFR), would act as a check on the PTI. The current draft proposal does not specify what will be the consequence of an unfavourable IANA Functions Review.

Some other areas of focus going forward relate to the IFR team inclusion in ICANN bylaws along the lines of the AOC established in 2009.[16] Also, ensuring the IFR team clarifies the scope of separability. The circumstances and procedures in place for pulling the IANA contract away if it has been established that ICANN is not fulfilling it contractual agreements. This will be a key accountability mechanism and deterrent for ICANN controlling the exercise of its influence.

CCWG Accountability

Work Stream (WS1): Responsible for drafting a mechanism for enhancing ICANN accountability, which must be in place before the IANA stewardship transition.

Work Stream (WS2): Addressing long term accountability topics which may extend beyond the IANA Stewardship Transition.

The IANA transition was recognized to be dependent on ICANN’s wider accountability, and this has exposed the trust issues between community and leadership and the proposal must be viewed in this context. The CCWG Draft Proposal attempts 4 significant new undertakings:

A. Restating ICANN’s Mission, Commitments, and Core Values, and placing those into the ICANN Bylaws. The CCWG has recommended that some segments of the Affirmation of Commitments (AOC)– a contract on operating principles agreed upon between ICANN and the United States government – be absorbed into the Corporation’s bylaws.

B. Establishing certain bylaws as “Fundamental Bylaws” that cannot be altered by the ICANN Board acting unilaterally, but over which stakeholders have prior approval rights;

C. Creating a formal “membership” structure for ICANN, along with “community empowerment mechanisms”. Some of the community empowerment mechanisms including (a) remove individual Board members, (b) recall the entire Board, (c) veto or approve changes to the ICANN Bylaws, Mission Statement, Commitments, and Core Values; and (d) to veto Board decisions on ICANN’s Strategic Plan and its budget;

D. Enhancing and strengthening ICANN's Independent Review Process (IRP) by creating a standing IRP Panel empowered to review actions taken by the corporation for compliance both with stated procedures and with the Bylaws, and to issue decisions that are binding upon the ICANN Board.

The key questions likely to be raised at ICANN 53 on several of these proposals will likely concern how these empowerment mechanisms affect the “legal nature” of the community.

Membership and Accountability

At the heart of the distrust between the ICANN Board and the community is the question of membership. ICANN as a corporation is a private sector body that is largely unregulated, with no natural competitors, cash-rich and directly or indirectly supports many of its participants and other Internet governance processes. Without effective accountability and transparency mechanisms, the opportunities for distortion, even corruption, are manifold. In such an environment, placing limitations on the Board’s power is critical to invoke trust. Three keys areas of accountability related to the Board include: no mechanisms for recall of individual board directors; the board’s ability to amend the company’s constitution (its bylaws), and the track record of board reconsideration requests.[17]

With no membership, ICANN’s directors represent the end of the line in terms of accountability. While there is a formal mechanism to review board decisions, the review is conducted by a subset of the same people. The CCWG’s proposal to create SOs/ACs as unincorporated “members” with Articles of Association has met with a lot of discussion, especially in the Governmental Advisory Council (GAC).[18] The GAC has posed several critical questions on this set up, some of which are listed here:

- Can a legal person created and acting on behalf of the GAC become a member of ICANN, even though the GAC does not appoint Board members?

- If GAC does not wish to become a member, how could it still be associated to the exercise of the 6 (community empowerment mechanisms) powers?

- It is still unclear what the liability of members of future “community empowered structures” would be.

- What are the legal implications on rights, obligations and liabilities of an informal group like the GAC creating an unincorporated association (UA) and taking decisions as such UA, from substantial (like exercising the community powers) to clerical (appointing its board, deciding on its financing) and whether there are implications when the members of such an UA are Governments?

Any proposal to strengthen accountability of ICANN needs to provide for membership so that there is ability to remove directors, creates financial accountability by receiving financial accounts and appointing editors and can check the ICANN’s board power to change bylaws without recourse to a higher authority.

Constitutional Undertaking

David Post and Danielle Kehl have pointed out that the CCWG correctly identifies the task it is undertaking – to ensure that ICANN’s power is adequately and appropriately constrained – as a “constitutional” one.[19] Their interpretation is based on the view that even if ICANN is not a true “sovereign,” it can usefully be viewed as one for the purpose of evaluating the sufficiency of checks on its power. Subsequently, the CCWG Draft Proposal, and ICANN’s accountability post-transition, can be understood and analyzed as a constitutional exercise, and that the transition proposal should meet constitutional criteria. Further, from this view the CCWG draft reflects the reformulation of ICANN around the broadly agreed upon constitutional criteria that should be addressed. These include:

- A clear enumeration of the powers that the corporation can exercise, and a clear demarcation of those that it cannot exercise.

- A division of the institution’s powers, to avoid concentrating all powers in one set of hands, and as a means of providing internal checks on its exercise.

- Mechanism(s) to enforce the constraints of (1) and (2) in the form of meaningful remedies for violations.

Their comments reflect that they support CCWG in their approach and progress made in designing a durable accountability structure for a post-transition ICANN. However, they have stressed that a number of important omissions and/or clarifications need to be addressed before they can be confident that these mechanisms will, in practice, accomplish their mission. One such suggestion relates to ICANN’s policy role and PTI technical role separability. Given ICANN’s position in the DNS hierarchy gives it the power to impose its policies, via the web of contracts with and among registries, registrars, and registrants, on all users of the DNS, a constitutional balance for the DNS must preserve and strengthen the separation between DNS policy-making and policy-implementation. Importantly, they have clarified that even if ICANN has the power to choose what policies are in the best interest of the community it is not free to impose them on the community. ICANN's role is a critical though narrow one: to organize and coordinate the activities of that stakeholder community – which it does through its various Supporting Organizations, Advisory Committees, and Constituencies – and to implement the consensus policies that emerge from that process. Their comments on the CCWG draft call for stating this clarification explicitly and institutionalizing separability to be guided by this critical safeguard against ICANN’s abuse of its power over the DNS.

An effective implementation of this limitation will help clarify the role mechanisms being proposed such as the PTI and is critical for creating sustainable mechanisms, post-transition. More importantly, clarifying ICANN’s mission would ensure that in the post-transition communities could challenge its decisions on the basis that it is not pertaining to the role outlined or based on strengthening the stability and security of the DNS. Presently, it is very unclear where ICANN can interfere in terms of policymaking and implementation.

Other Issues

Other issues expected to be raised in the context of ICANN's overall accountabiltiy will likey concern the following:

Strengthening financial transparency and oversight

Given the rapid growth of the global domain name industry, one would imagine that ICANN is held up to the same standard of accountability as laid down in the right to information mechanisms countries such as India. CIS has been raising this issue for a while and has managed to received the list of ICANN’s current domain name revenues.[20]

By sharing this information, ICANN has shown itself responsive to repeated requests for transparency however, the shared revenue data is only for the fiscal year ending June 2014, and historical revenue data is still not publicly available. Neither is a detailed list (current and historical) of ICANN’s expenditures publicly available. Accountability mechanisms and discussions must seek that ICANN provide the necessary information during its regular Quarterly Stakeholder Reports, as well as on its website.

Strengthening transparency

A key area of concern is ICANN's unchecked influence and growing role as an institution in the IG space. Seen in the light of the impending transition, the transparency concerns gain significance and given ICANN's vocal interests in maintaining the status quo of its role in DNS Management. While financial statements (current and historic) are public and community discussions are generally open, the complexity of the contractual arrangements in place tracking the financial reserves available to ICANN through these processes are not sufficient.

Further, ICANN as a monopoly is presently constrained only by the NTIA review and few internal mechanisms like the Documentary Information Disclosure Policy (DIDP)[21], Ombudsman[22], Reconsideration and Independent Review[23] and the Accountability and Transparency Review (ATRT)[24]. These mechanisms are facing teething issues and some do not conform to the principles of natural justice. For example, a Reconsideration Request can be filed if one is aggrieved by an action of ICANN’s Board or staff. Under ICANN’s By-laws, it is the Board Governance Committee, comprising ICANN Board members, that adjudicates Reconsideration Requests.[25]

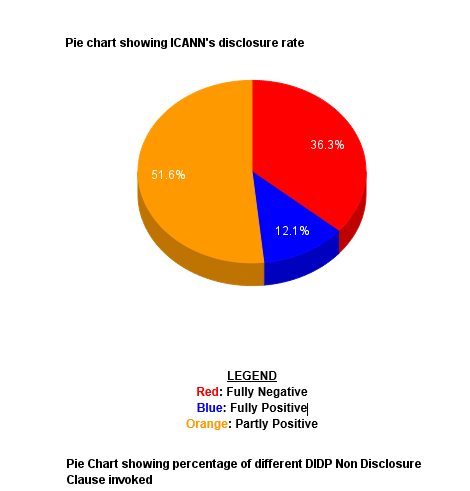

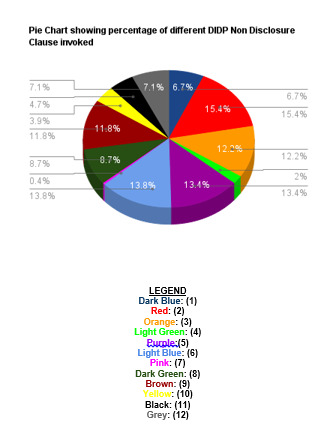

Responses to the DIDP requests filed by CIS reveal that the mechanism in its current form, is not sufficient to provide the transparency necessary for ICANN’s functioning. For instance, in the response to DIDP pertaining to the Ombudsman Requests[26], ICANN cites confidentiality as a reason to decline providing information as making Ombudsman Requests public would violate ICANN Bylaws, toppling the independence and integrity of the Ombudsman. Over December ’14 and January ’15, CIS sent 10 DIDP requests to ICANN with an aim was to test and encourage discussions on transparency from ICANN. We have received responses for 9 of our requests, and in 7 of those responses ICANN provides very little new information and moving forward we would stress the improvements of existing mechanisms along with introduction of new oversight and reporting parameters towards facilitating the transition process.[27]

[1]John Sweeting and others, 'CRISP Process Overview' (ARIN 35, 2015) https://regmedia.co.uk/2015/04/30/crisp_panel.pdf

[2]Andrew Sullivan, [Ianaplan] Update On IANA Transition & Negotiations With ICANN (2015), Email http://www.ietf.org/mail-archive/web/ianaplan/current/msg01680.html

[3]Milton Mueller, ‘ICANN WANTS AN IANA FUNCTIONS MONOPOLY – WILL IT WRECK THE TRANSITION PROCESS TO GET IT?’ (Internet Governance Project, 28 April 2015) http://www.internetgovernance.org/2015/04/28/icann-wants-an-iana-functions-monopoly-and-its-willing-to-wreck-the-transition-process-to-get-it/#comment-40045

[4]Tony Smith, 'Event Wrap: ICANN 52' (APNIC Blog, 20 February 2015) http://blog.apnic.net/2015/02/20/event-wrap-icann-52/

[5]Internet Engineering Task Force, 'IPROC – IETF Protocol Registries Oversight Committee' (2015) https://www.ietf.org/iana/iproc.html

[6]Axel Pawlik, Numbers Community Proposal Contact Points With CWG’S Draft IANA Stewardship Transition Proposal (2015), Email http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-cwg-stewardship-draft-proposal-22apr15/msg00003.html

[7]Jari Arkko, Re: [Ianaplan] CWG Draft And Its Impact On The IETF (2015), Email http://www.ietf.org/mail-archive/web/ianaplan/current/msg01843.html

[8]Milton Mueller, Comments Of The Internet Governance Project (2015), Email http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-cwg-stewardship-draft-proposal-22apr15/msg00021.html

[9]Richard Hill, Initial Comments On CWG-Stewardship Draft Proposal (2015), Email http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-cwg-stewardship-draft-proposal-22apr15/msg00000.html

[10]Brenden Kuerbis, 'Why The Post-Transition IANA Should Be A Nonprofit Public Benefit Corporation' (Internet Governance Project, 18 May 2015) http://www.internetgovernance.org/2015/05/18/why-the-post-transition-iana-should-be-a-nonp

[11]ICANN Board Comments On 2Nd Draft Proposal Of The Cross Community Working Group To Develop An IANA Stewardship Transition Proposal On Naming Related Functions (20 May 2015) http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-cwg-stewardship-draft-proposal-22apr15/pdfrIUO5F9nY4.pdf

[12]Comments Of Government Of India On The ‘2nd Draft Proposal Of The Cross Community Working Group To Develop An IANA Stewardship Transition Proposal On Naming Related Functions’ (2015) http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-cwg-stewardship-draft-proposal-22apr15/pdfJGK6yVohdU.pdf

[13]Anders Hektor, Sweden Comments To CWG-Stewardship (2015), Email http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-cwg-stewardship-draft-proposal-22apr15/msg00016.html

[14]Brenden Kuerbis, 'Why The Post-Transition IANA Should Be A Nonprofit Public Benefit Corporation |' (Internet Governance Project, 18 May 2015) http://www.internetgovernance.org/2015/05/18/why-the-post-transition-iana-should-be-a-nonprofit-public-benefit-corporation/

[15]Comments Of Government Of India On The ‘2nd Draft Proposal Of The Cross Community Working Group To Develop An IANA Stewardship Transition Proposal On Naming Related Functions’ (2015) http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-cwg-stewardship-draft-proposal-22apr15/pdfJGK6yVohdU.pdf

[16]Kieren McCarthy, 'Internet Kingmakers Drop Ego, Devise Future Of DNS, IP Addys Etc' (The Register, 24 April 2015) http://www.theregister.co.uk/2015/04/24/internet_kingmakers_drop_ego_devise_future_of_the_internet/

[17]Emily Taylor, ICANN: Bridging The Trust Gap (Paper Series No. 9, Global Commission on Internet Governance March 2015) https://regmedia.co.uk/2015/04/02/gcig_paper_no9-iana.pdf

[18]Milton Mueller, 'Power Shift: The CCWG’S ICANN Membership Proposal' (Internet Governance Project, 4 June 2015) http://www.internetgovernance.org/2015/06/04/power-shift-the-ccwgs-icann-membership-proposal/

[19]David Post, Submission Of Comments On CCWG Draft Initial Proposal (2015), Email http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-ccwg-accountability-draft-proposal-04may15/msg00050.html

[20] Hariharan, 'ICANN reveals hitherto undisclosed details of domain names revenues', 8 December, 2014 See: http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/cis-receives-information-on-icanns-revenues-from-domain-names-fy-2014

[21] ICANN, Documentary Information Disclosure Policy See: https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/didp-2012-02-25-en

[22] ICANN Accountability, Role of the Ombudsman https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/accountability/ombudsman-en

[23] ICANN Reconsideration and independent review, ICANN Bylaws, Article IV, Accountability and Review https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/reconsideration-and-independent-review-icann-bylaws-article-iv-accountability-and-review

[24] ICANN Accountability and Transparency Review Final Recommendations https://www.icann.org/en/system/files/files/final-recommendations-31dec13-en.pdf

[25] ICANN Bylaws Article iv, Section 2 https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/governance/bylaws-en#IV

[26] ICANN Response to DIDP Ombudsman https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/20141228-1-ombudsman-2015-01-28-en

[27] Table of CIS DIDP Requests See: http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/table-of-cis-didp-requests/at_download/file

IANA Transition Stewardship & ICANN Accountability (I)

In developing these papers we have been guided by Kieren McCarthy's writings in The Register, Milton Mueller writings on the Internet Governance Project, Rafik Dammak emails on the mailings lists, the constitutional undertaking argument made in the policy paper authored by Danielle Kehl & David Post for New America Foundation.

Introduction

The 53rd ICANN conference in Buenos Aires was pivotal as it marked the last general meeting before the IANA transition deadline on 30th September, 2015. The multistakeholder process initiated seeks communities to develop transition proposals to be consolidated and reviewed by the the IANA Stewardship Transition Coordination Group (ICG). The names, number and protocol communities convened at the conference to finalize the components of the transition proposal and to determine the way forward on the transition proposals. The Protocol Parameters (IANA PLAN Working Group) submitted to ICG on 6 January 2015, while the Numbering Resources (CRISP Team) submitted on 15 January 2015. The Domain Names (CWG-Stewardship) submitted its second draft to ICG on 25 June 2015. The ICG had a face-to-face meeting in Buenos Aires and their proposal to transition the stewardship of the IANA functions is expected to be out for public comment July 31 to September 8, 2015.

Parallelly, the CCWG on Enhancing ICANN Accountability offered its first set of proposals for public comment in June 2015 and organised two working sessions at ICANN'53. More recently, the CCWG met in Paris focusing on the proposed community empowerment mechanisms, emerging concerns and progress on issues so far. CIS reserves its comments to the CCWG till the second round of comments expected in July.

This working paper explains the IANA Transition, its history and relevance to management of the Internet. It provides an update on the processes so far, including the submissions by the Indian government and highlights areas of concern that need attention going forward.

How is IANA Transition linked to DNS Management?

The IANA transition presents a significant opportunity for stakeholders to influence the management and governance of the global network. The Domain Name System (DNS), which allows users to locate websites by translating the domain name with corresponding Internet Protocol address, is critical to the functioning of the Internet. The DNS rests on the effective coordination of three critical functions—the allocation of IP Addresses (the numbers function), domain name allocation (the naming function), and protocol parameters standardisation (the protocols function).

History of the ICANN-IANA Functions contract

Initially, these key functions were performed by individuals and public and private institutions. They either came together voluntarily or through a series of agreements and contracts brokered by the Department of Commerce’s National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) and funded by the US government. With the Internet's rapid expansion and in response to concerns raised about its increasing commercialization as a resource, a need was felt for the creation of a formal institution that would take over DNS management. This is how ICANN, a California-based private, non-profit technical coordination body, came at the helm of DNS and related issues. Since then, ICANN has been performing the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) functions under a contract with the NTIA, and is commonly referred to as the IANA Functions Operator.

IANA Functions

In February 2000, the NTIA entered into the first stand-alone IANA Functions HYPERLINK "http://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/sf_26_pg_1-2-final_award_and_sacs.pdf"contract[1] with ICANN as the Operator. While the contractual obligations have evolved over time, these are largely administrative and technical in nature including:

(1) the coordination of the assignment of technical Internet protocol parameters;

(2) the allocation of Internet numbering resources; and

(3) the administration of certain responsibilities associated with the Internet DNS root zone management;

(4) other services related to the management of the ARPA and top-level domains.

ICANN has been performing the IANA functions under this oversight, primarily as NTIA did not want to let go of complete control of DNS management. Another reason was to ensure NTIA's leverage in ensuring that ICANN’s commitments, conditional to its incorporation, were being met and that it was sticking to its administrative and technical role.

Root Zone Management—Entities and Functions Involved

NTIA' s involvement has been controversial particularly in reference to the Root Zone Management function, which allows allows for changes to the HYPERLINK "http://www.internetsociety.org/sites/default/files/The Internet Domain Name System Explained for Non-Experts (ENGLISH).pdf"highest level of the DNS namespace[2] by updating the databases that represent that namespace. DNS namespace is defined to be the set of names known as top-level domain names or TLDs which may be at the country level (ccTLDs or generic (gTLDs). This HYPERLINK "https://static.newamerica.org/attachments/2964-controlling-internet-infrastructure/IANA_Paper_No_1_Final.32d31198a3da4e0d859f989306f6d480.pdf"function to maintain the Root was split into two parts[3]—with two separate procurements and two separate contracts. The operational contract for the Primary (“A”) Root Server was awarded to VeriSign, the IANA Functions Contract—was awarded to ICANN.

These contracts created contractual obligations for ICANN as IANA Root Zone Management Function Operator, in co-operation with Verisign as the Root Zone Maintainer and NTIA as the Root Zone Administrator whose authorisation is explicitly required for any requests to be implemented in the root zone. Under this contract, ICANN had responsibility for the technical functions for all three communities under the IANA Functions contract.

ICANN also had policy making functions for the names community such as developing HYPERLINK "https://www.iana.org/domains/root/files"rules and procedures and policies under HYPERLINK "https://www.iana.org/domains/root/files"which any changes to the Root Zone File[4] were to be proposed, including the policies for adding new TLDs to the system. The policy making of numbers and protocols is with IETF and RIRs respectively. HYPERLINK "http://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/ntias_role_root_zone_management_12162014.pdf"NTIA role in root zone management[5] is clerical and judgment free with regards to content. It authorizes implementation of requests after verifying whether procedures and policies are being followed.

This contract was subject to extension by mutual agreement and failure of complying with predefined commitments could result in the re-opening of the contract to another entity through a Request For Proposal (RFP). In fact, in 2011 HYPERLINK "http://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/11102011_solicitation.pdf"NTIA issued a RFP pursuant to ICANNHYPERLINK "http://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/11102011_solicitation.pdf"'HYPERLINK "http://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/11102011_solicitation.pdf"s Conflict of Interest Policy.[6]

Why is this oversight needed?

The role of the Administrator becomes critical for ensuring the security and operation of the Internet with the Root Zone serving as the directory of critical resources. In December 2014, HYPERLINK "http://www.theregister.co.uk/2015/04/30/confidential_information_exposed_over_300_times_in_icann_security_snafu/"a report revealed 300 incidents of internal security breaches[7] some of which were related to the Centralized Zone Data System (CZDS) – where the internet core root zone files are mirrored and the WHOIS portal. In view of the IANA transition and given ICANN's critical role in maintaining the Internet infrastructure, the question which arises is if NTIA will let go of its Administrator role then which body should succeed it?

Transition announcement and launch of process

On 14 March 2014, the NTIA HYPERLINK "http://www.ntia.doc.gov/press-release/2014/ntia-announces-intent-transition-key-internet-domain-name-functions"announced[8] “its intent to transition key Internet domain name functions to the global multistakeholder community”. These key Internet domain name functions refer to the IANA functions. For this purpose, the NTIA HYPERLINK "http://www.ntia.doc.gov/press-release/2014/ntia-announces-intent-transition-key-internet-domain-name-functions"asked[9] the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) to convene a global multistakeholder process to develop a transition proposal which has broad community support and addresses the following four principles:

- Support and enhance the multistakeholder model;

- Maintain the security, stability, and resiliency of the Internet DNS;

- Meet the needs and expectation of the global customers and partners of the IANA services; and

- Maintain the openness of the Internet.

The transition process has been split according to the three main communities naming, numbers and protocols.

Structure of the Transition Processes

ICANN performs both technical functions and policy-making functions. The technical functions are known as IANA functions and these are performed by ICANN are for all three communities.

I. Naming function: ICANN performs technical and policy-making for the names community. The technical functions are known as IANA functions and the policy-making functions relates to their role in deciding whether .xxx or .sucks should be allowed amongst other issues. There are two parallel streams of work focusing on the naming community that are crucial to completing the transition. The first, Cross-Community Working Group to Develop an IANA Stewardship Transition Proposal on Naming Related Functions will enable NTIA to transition out of its role in the DNS. Therefore, accountability of IANA functions is the responsibility of the CWG and accountability of policy-making functions is outside its scope. CWG has submitted its second draft to the ICG.

The second, Cross-Community Working Group on Accountability (CCWG-Accountability) is identifying necessary reforms to ICANN’s bylaws and processes to enhance the organization’s accountability to the global community post-transition. Therefore accountability of IANA functions is outside the scope of the CCWG. The CCWG on Enhancing ICANN Accountability offered its first set of proposals for public comment in June 2015.

II. Numbers function: ICANN performs only technical functions for the numbers community. The policy-making functions for numbers are performed by RIRs. CRISP is focusing on the IANA functions for numbers and has submitted their proposal to the ICG earlier this year.

III. Protocols function: ICANN performs only technical functions for the protocols community. The policy-making functions for protocols are performed by IETF. IETF-WG is focusing on the IANA functions for protocols and has submitted their proposal to the ICG earlier this year.

Role of ICG

After receiving the proposals from all three communities the ICG must combine these proposals into a consolidated transition proposal and then seek public comment on all aspects of the plan. ICG’s role is crucial, because it must build a public record for the NTIA on how the three customer group submissions tie together in a manner that ensures NTIA’s HYPERLINK "http://www.ntia.doc.gov/press-release/2014/ntia-announces-intent-transition-key-internet-domain-name-functions"criteria[10] are met and institutionalized over the long term. Further, ICG's final submission to NTIA must include a plan to enhance ICANN’s accountability based on the CCWG-Accountability proposal.

NTIA Leverage

Reprocurement of the IANA contract is HYPERLINK "http://www.newamerica.org/oti/controlling-internet-infrastructure/"essential for ICANNHYPERLINK "http://www.newamerica.org/oti/controlling-internet-infrastructure/"'HYPERLINK "http://www.newamerica.org/oti/controlling-internet-infrastructure/"sHYPERLINK "http://www.newamerica.org/oti/controlling-internet-infrastructure/" legitimacy[11] in the DNS ecosystem and the authority to reopen the contract and in keeping the policy and operational functions separate meant that, NTIA could simply direct VeriSign to follow policy directives being issued from the entity replacing ICANN if they were deemed to be not complying. This worked as an effective leverage for ICANN complying to their commitments even if it is difficult to determine how this oversight was exercised. Perceptually, this has been interpreted as a broad overreach particularly, in the context of issues of sovereignty associated with ccTLDs and the gTLDs in their influence in shaping markets. However, it is important to bear in mind that the NTIA authorization comes after the operator, ICANN—has validated the request and does not deal with the substance of the request rather focuses merely on compliance with outlined procedure.

NTIA's role in the transition process

NTIA in its HYPERLINK "http://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/ntia_second_quarterly_iana_report_05.07.15.pdf"Second Quarterly Report to the Congress[12] for the period of February 1-March 31, 2015 has outlined some clarifications on the process ahead. It confirmed the flexibility of extending the contract or reducing the time period for renewal, based on community decision. The report also specified that the NTIA would consider a proposal only if it has been developed in consultation with the multi-stakeholder community. The transition proposal should have broad community support and does not seek replacement of NTIA's role with a government-led or intergovernmental organization solution. Further the proposal should maintain security, stability, and resiliency of the DNS, the openness of the Internet and must meet the needs and expectations of the global customers and partners of the IANA services. NTIA will only review a comprehensive plan that includes all these elements.

Once the communities develop and ICG submits a consolidated proposal, NTIA will ensure that the proposal has been adequately “stress tested” to ensure the continued stability and security of the DNS. NTIA also added that any proposed processes or structures that have been tested to see if they work, prior to the submission—will be taken into consideration in NTIA's review. The report clarified that NTIA will review and assess the changes made or proposed to enhance ICANN’s accountability before initiating the transition.

Prior to ICANN'53, Lawrence E. Strickling Assistant Secretary for Communications and Information and NTIA Administrator HYPERLINK "http://www.ntia.doc.gov/blog/2015/stakeholder-proposals-come-together-icann-meeting-argentina"has posed some questions for consideration[13] by the communities prior to the completion of the transition plan. The issues and questions related to CCWG-Accountability draft are outlined below:

- Proposed new or modified community empowerment tools—how can the CCWG ensure that the creation of new organizations or tools will not interfere with the security and stability of the DNS during and after the transition? Do these new committees and structures create a different set of accountability questions?

- Proposed membership model for community empowerment—have other possible models been thoroughly examined, detailed, and documented? Has CCWG designed stress tests of the various models to address how the multistakeholder model is preserved if individual ICANN Supporting Organizations and Advisory Committees opt out?

- Has CCWG developed stress tests to address the potential risk of capture and barriers to entry for new participants of the various models? Further, have stress tests been considered to address potential unintended consequences of “operationalizing” groups that to date have been advisory in nature?

- Suggestions on improvements to the current Independent Review Panel (IRP) that has been criticized for its lack of accountability—how does the CCWG proposal analyze and remedy existing concerns with the IRP?

- In designing a plan for improved accountability, should the CCWG consider what exactly is the role of the ICANN Board within the multistakeholder model? Should the standard for Board action be to confirm that the community has reached consensus, and if so, what accountability mechanisms are needed to ensure the Board operates in accordance with that standard?

- The proposal is primarily focused on the accountability of the ICANN Board—has the CCWG considered accountability improvements that would apply to ICANN management and staff or to the various ICANN Supporting Organizations and Advisory Committees?

- NTIA has also asked the CCWG to build a public record and thoroughly document how the NTIA criteria have been met and will be maintained in the future.

- Has the CCWG identified and addressed issues of implementation so that the community and ICANN can implement the plan as expeditiously as possible once NTIA has reviewed and accepted it.

NTIA has also sought community’s input on timing to finalize and implement the transition plan if it were approved. The Buenos Aires meeting became a crucial point in the transtion process as following the meeting, NTIA will need to make a determination on extending its current contract with ICANN. Keeping in mind that the community and ICANN will need to implement all work items identified by the ICG and the Working Group on Accountability as prerequisites for the transition before the contract can end, the community’s input is critical.

NTIA's legal standing

On 25th February, 2015 the US Senate Committee on Commerce, Science & Transportation on 'Preserving the Multi-stakeholder Model of Internet Governance'[14] heard from NTIA head Larry Strickling, Ambassador Gross and Fadi Chehade. The hearing sought to plug any existing legal loopholes, and tighten its administrative, technical, financial, public policy, and political oversight over the entire process no matter which entity takes up the NTIA function. The most important takeaway from this Congressional hearing came from Larry Strickling’s testimony[15] who stated that NTIA has no legal or statutory responsibility to manage the DNS.

If the NTIA does not have the legal responsibility to act, and its role was temporary; on what basis is the NTIA driving the current IANA Transition process without the requisite legal authority or Congressional mandate? Historically, the NTIA oversight, effectively devised as a leverage for ICANN fulfilling its commitments have not been open to discussion. HYPERLINK "http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-ccwg-accountability-draft-proposal-04may15/pdfnOquQlhsmM.pdf"Concerns have also been raised[16] on the lack of engagement with non-US governments, organizations and persons prior to initiating or defining the scope and conditions of the transition. Therefore, any IANA transition plan must consider this lack of consultation, develop a multi-stakeholder process as the way forward—even if the NTIA wants to approve the final transition plan.

Need to strengthen Diversity Principle

Following submissions by various stakeholders raising concerns regarding developing world participation, representation and lack of multilingualism in the transition process—the Diversity Principle was included by ICANN in the Revised Proposal of 6 June 2014. Given that representatives from developing countries as well as from stakeholder communities outside of the ICANN community are unable to productively involve themselves in such processes because of lack of multilingualism or unfamiliarity with its way of functioning merely mentioning diversity as a principle is not adequate to ensure abundant participation. As CIS has pointed out[17] before issues have been raised about the domination by North American or European entities which results in undemocratic, unrepresentative and non-transparent decision-making in such processes. Accordingly, all the discussions in the process should be translated into multiple native languages of participants in situ, so that everyone participating in the process can understand what is going on. Adequate time must be given for the discussion issues to be translated and circulated widely amongst all stakeholders of the world, before a decision is taken or a proposal is framed. This was a concern raised in the recent CCWG proposal which was extended as many communities did not have translated texts or adequate time to participate.

Representation of the global multistakeholder community in ICG

Currently, the Co-ordination Group includes representatives from ALAC, ASO, ccNSO, GNSO, gTLD registries, GAC, ICC/BASIS, IAB, IETF, ISOC, NRO, RSSAC and SSAC. Most of these representatives belong to the ICANN community, and is not representative of the global multistakeholder community including governments. This is not representative of even a multistakeholder model which the US HYPERLINK "http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/iana-transition-suggestions-for-process-design"gHYPERLINK "http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/iana-transition-suggestions-for-process-design"ovHYPERLINK "http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/iana-transition-suggestions-for-process-design"ernment HYPERLINK "http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/iana-transition-suggestions-for-process-design"has announced[18] for the transition; nor in the multistakeholder participation spirit of NETmundial. Adequate number of seats on the Committee must be granted to each stakeholder so that they can each coordinate discussions within their own communities and ensure wider and more inclusive participation.

ICANN's role in the transition process

Another issue of concern in the pre-transition process has been ICANN having been charged with facilitating this transition process. This decision calls to question the legitimacy of the process given that the suggestions from the proposals envision a more permanent role for ICANN in DNS management. As Kieren McCarthy has pointed out [19]ICANN has taken several steps to retain the balance of power in managing these functions which have seen considerable pushback from the community. These include an attempt to control the process by announcing two separate processes[20] – one looking into the IANA transition, and a second at its own accountability improvements – while insisting the two were not related. That effort was beaten down[21] after an unprecedented letter by the leaders of every one of ICANN's supporting organizations and advisory committees that said the two processes must be connected.

Next, ICANN was accused of stacking the deck[22] by purposefully excluding groups skeptical of ICANN’s efforts, and by trying to give ICANN's chairman the right to personally select the members of the group that would decide the final proposal. That was also beaten back. ICANN staff also produced a "scoping document"[23], that pre-empt any discussion of structural separation and once again community pushback forced a backtrack.[24]

These concerns garner more urgency given recent developments with the community working HYPERLINK "http://www.ietf.org/mail-archive/web/ianaplan/current/msg01680.html"groups[25] and ICANN divisive view of the long-term role of ICANN in DNS management. Further, given HYPERLINK "https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yGwbYljtNyI#t=1164"ICANNHYPERLINK "https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yGwbYljtNyI#t=1164" HYPERLINK "https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yGwbYljtNyI#t=1164"President Chehade’s comments that the CWG is not doing its job[26], is populated with people who do not know anything and the “IANA process needs to be left alone as much as possible”. Fadi also specified that ICANN had begun the formal process of initiating a direct contract with VeriSign to request and authorise changes to be implemented by VeriSign. While ICANN may see itself without oversight in this relationship with VeriSign, it is imperative that proposals bear this plausible outcome in mind and put forth suggestions to counter this.

The HYPERLINK "http://www.ietf.org/mail-archive/web/ianaplan/current/msg01680.html"update from IETF on the ongoing negotiation with ICANN on their proposal[27] related to protocol parameters has also flagged that ICANN is unwilling to cede to any text which would suggest ICANN relinquishing its role in the operations of protocol parameters to a subsequent operator, should the circumstances demand this. ICANN has stated that agreeing to such text now would possibly put them in breach of their existing agreement with the NTIA. Finally, HYPERLINK "https://twitter.com/arunmsukumar/status/603952197186035712"ICANN HYPERLINK "https://twitter.com/arunmsukumar/status/603952197186035712"Board Member, Markus Kummer[28] stated that if ICANN was to not approve any aspect of the proposal this would hinder the consensus and therefore, the transition would not be able to move forward.

ICANN has been designated the convenor role by the US government on basis of its unique position as the current IANA functions contractor and the global coordinator for the DNS. However it is this unique position itself which creates a conflict of interest as in the role of contractor of IANA functions, ICANN has an interest in the outcome of the process being conducive to ICANN. In other words, there exists a potential for abuse of the process by ICANN, which may tend to steer the process towards an outcome favourable to itself.

Therefore there exists a strong rationale for defining the limitations of the role of ICANN as convenor. The community has suggested that ICANN should limit its role to merely facilitating discussions and not extend it to reviewing or commenting on emerging proposals from the process. Additional safeguards need to be put in place to avoid conflicts of interest or appearance of conflicts of interest. ICANN should further not compile comments on drafts to create a revised draft at any stage of the process. Additionally, ICANN staff must not be allowed to be a part of any group or committee which facilitates or co-ordinates the discussion regarding IANA transition.

How is the Obama Administration and the US Congress playing this?

Even as the issues of separation of ICANN's policy and administrative role remained unsettled, in the wake of the Snowden revelations, NTIA initiated the long due transition of the IANA contract oversight to a global, private, non-governmental multi-stakeholder institution on March 14, 2014. This announcement immediately raised questions from Congress on whether the transition decision was dictated by technical considerations or in response to political motives, and if the Obama Administration had the authority to commence such a transition unilaterally, without prior open stakeholder consultations. Republican HYPERLINK "http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/06/02/us-usa-internet-icann-idUSKBN0OI2IJ20150602"lawmakers have raised concerns about the IANA transition plan [29]worried that it may allow other countries to capture control.

More recently, HYPERLINK "https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2251"Defending Internet Freedom Act[30] has been re-introduced to US Congress. This bill seeks ICANN adopt the recommendations of three internet community groups, about the transition of power, before the US government relinquishes control of the IANA contract. The bill also seeks ownership of the .gov and .mil top-level domains be granted to US government and that ICANN submit itself to the US Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), a legislation similar to the RTI in India, so that its records and other information gain some degree of public access.It has also been asserted by ICANN that neither NTIA nor the US Congress will approve any transition plan which leaves open the possibility of non-US IANA Functions Operator in the future.

Funding of the transition

The Obama administration is also HYPERLINK "http://www.broadcastingcable.com/news/washington/house-bill-blocks-internet-naming-oversight-handoff/141393"fighting a Republican-backed Commerce, Justice, Science, and HYPERLINK "http://www.broadcastingcable.com/news/washington/house-bill-blocks-internet-naming-oversight-handoff/141393"Related Agencies Appropriations Act (H.R. 2578)[31] which seeks to block NTIA funding the IANA transition. One provision of this bill restricts NTIA from using appropriated dollars for IANA stewardship transition till the end of the fiscal year, September 30, 2015 also the base period of the contact in function. This peculiar proviso in the Omnibus spending bill actually implies that Congress believes that the IANA Transition should be delayed with proper deliberation, and not be rushed as ICANN and NTIA are inclined to.

The IANA Transition cannot take place in violation of US Federal Law that has defunded it within a stipulated time-window. At the Congressional Internet Caucus in January 2015, NTIA head Lawrence Strickling clarified that NTIA will “not use appropriated funds to terminate the IANA functions...” or “to amend the cooperative agreement with Verisign to eliminate NTIA's role in approving changes to the authoritative root zone file...”. This implicitly establishes that the IANA contract will be extended, and Strickling confirmed that there was no hard deadline for the transition.

DOTCOM Act

The Communications and Technology Subcommittee of the House Energy and Commerce Committee HYPERLINK "http://energycommerce.house.gov/markup/communications-and-technology-subcommittee-vote-dotcom-act"amended the DOTCOM Act[32], a bill which, in earlier drafts, would have halted the IANA functions transition process for up to a year pending US Congressional approval. The bill in its earlier version represented unilateral governmental interference in the multistakeholder process. The new bill reflects a much deeper understanding of, and confidence in, the significant amount of work that the global multistakeholder community has undertaken in planning both for the transition of IANA functions oversight and for the increased accountability of ICANN. The amended DOTCOM Act would call for the NTIA to certify – as a part of a proposed GAO report on the transition – that “the required changes to ICANN’s by-laws contained in the final report of ICANN’s Cross Community Working Group on Enhancing ICANN Accountability and the changes to ICANN’s bylaws required by ICANN’s IANA have been implemented.” The bill enjoys immense bipartisan support[33], and is being lauded as a prudent and necessary step for ensuring the success of the IANA transition.

[1] IANA Functions Contract <http://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/sf_26_pg_1-2-final_award_and_sacs.pdf> accessed 15th June 2015

[2] Daniel Karrenberg, The Internet Domain Name System Explained For Nonexperts <http://www.internetsociety.org/sites/default/files/The%20Internet%20Domain%20Name%20System%20Explained%20for%20Non-Experts%20(ENGLISH).pdf> accessed 15 June 2015

[3] David Post and Danielle Kehl, Controlling Internet Infrastructure The “IANA Transition” And Why It Matters For The Future Of The Internet, Part I (1st edn, Open Technology Institute 2015) <https://static.newamerica.org/attachments/2964-controlling-internet-infrastructure/IANA_Paper_No_1_Final.32d31198a3da4e0d859f989306f6d480.pdf> accessed 10 June 2015.

[4] Iana.org, 'IANA — Root Files' (2015) <https://www.iana.org/domains/root/files> accessed 11 June 2015.

[5] 'NTIA's Role In Root Zone Management' (2014). <http://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/ntias_role_root_zone_management_12162014.pdf> accessed 15 June 2015.

[6] Contract ( 2011) <http://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/11102011_solicitation.pdf> accessed 10 June 2015.

[7] Kieren McCarthy, 'Confidential Information Exposed Over 300 Times In ICANN Security Snafu' The Register (2015) <http://www.theregister.co.uk/2015/04/30/confidential_information_exposed_over_300_times_in_icann_security_snafu/> accessed 15 June 2015.

[8] NTIA, ‘NTIA Announces Intent To Transition Key Internet Domain Name Functions’ (2014) <http://www.ntia.doc.gov/press-release/2014/ntia-announces-intent-transition-key-internet-domain-name-functions> accessed 15 June 2015.

[9] NTIA, ‘NTIA Announces Intent To Transition Key Internet Domain Name Functions’ (2014) <http://www.ntia.doc.gov/press-release/2014/ntia-announces-intent-transition-key-internet-domain-name-functions> accessed 15 June 2015.

[10] NTIA, ‘NTIA Announces Intent To Transition Key Internet Domain Name Functions’ (2014) <http://www.ntia.doc.gov/press-release/2014/ntia-announces-intent-transition-key-internet-domain-name-functions> accessed 15 June 2015.

[11] David Post and Danielle Kehl, Controlling Internet Infrastructure The “IANA Transition” And Why It Matters For The Future Of The Internet, Part I (1st edn, Open Technology Institute 2015) <https://static.newamerica.org/attachments/2964-controlling-internet-infrastructure/IANA_Paper_No_1_Final.32d31198a3da4e0d859f989306f6d480.pdf> accessed 10 June 2015.

[12] National Telecommunications and Information Administration, 'REPORT ON THE TRANSITION OF THE STEWARDSHIP OF THE INTERNET ASSIGNED NUMBERS AUTHORITY (IANA) FUNCTIONS' (NTIA 2015) <http://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/ntia_second_quarterly_iana_report_05.07.15.pdf> accessed 10 July 2015.

[13] Lawrence Strickling, 'Stakeholder Proposals To Come Together At ICANN Meeting In Argentina' <http://www.ntia.doc.gov/blog/2015/stakeholder-proposals-come-together-icann-meeting-argentina> accessed 19 June 2015.

[14] Philip Corwin, 'NTIA Says Cromnibus Bars IANA Transition During Current Contract Term' <http://www.circleid.com/posts/20150127_ntia_cromnibus_bars_iana_transition_during_current_contract_term/> accessed 10 June 2015.

[15] Sophia Bekele, '"No Legal Basis For IANA Transition": A Post-Mortem Analysis Of Senate Committee Hearing' <http://www.circleid.com/posts/20150309_no_legal_basis_for_iana_transition_post_mortem_senate_hearing/> accessed 9 June 2015.

[16] Comments On The IANA Transition And ICANN Accountability Just Net Coalition (2015) <http://forum.icann.org/lists/comments-ccwg-accountability-draft-proposal-04may15/pdfnOquQlhsmM.pdf> accessed 12 June 2015.

[17] The Centre for Internet and Society, 'IANA Transition: Suggestions For Process Design' (2014) <http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/iana-transition-suggestions-for-process-design> accessed 9 June 2015.

[18] The Centre for Internet and Society, 'IANA Transition: Suggestions For Process Design' (2014) <http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/iana-transition-suggestions-for-process-design> accessed 9 June 2015.

[19] Kieren McCarthy, 'Let It Go, Let It Go: How Global DNS Could Survive In The Frozen Lands Outside US Control Public Comments On Revised IANA Transition Plan' The Register (2015) <http://www.theregister.co.uk/2015/05/26/iana_icann_latest/> accessed 15 June 2015.

[20] Icann.org, 'Resources - ICANN' (2014) <https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/process-next-steps-2014-08-14-en> accessed 13 June 2015.

[21] <https://www.icann.org/en/system/files/correspondence/crocker-chehade-to-soac-et-al-18sep14-en.pdf> accessed 10 June 2015.

[22] Richard Forno, '[Infowarrior] - Internet Power Grab: The Duplicity Of ICANN' (Mail-archive.com, 2015) <https://www.mail-archive.com/[email protected]/msg12578.html> accessed 10 June 2015.

[23] ICANN, 'Scoping Document' (2014) <https://www.icann.org/en/system/files/files/iana-transition-scoping-08apr14-en.pdf> accessed 9 June 2015.

[24] Milton Mueller, 'ICANN: Anything That Doesn’T Give IANA To Me Is Out Of Scope |' (Internetgovernance.org, 2014) <http://www.internetgovernance.org/2014/04/16/icann-anything-that-doesnt-give-iana-to-me-is-out-of-scope/> accessed 12 June 2015.

[25] Andrew Sullivan, '[Ianaplan] Update On IANA Transition & Negotiations With ICANN' (Ietf.org, 2015) <http://www.ietf.org/mail-archive/web/ianaplan/current/msg01680.html> accessed 14 June 2015.

[26] DNA Member Breakfast With Fadi Chehadé (2015-02-11) (The Domain Name Association 2015).

[27] Andrew Sullivan, '[Ianaplan] Update On IANA Transition & Negotiations With ICANN' (Ietf.org, 2015) <http://www.ietf.org/mail-archive/web/ianaplan/current/msg01680.html> accessed 14 June 2015.

[28] Mobile.twitter.com, 'Twitter' (2015) <https://mobile.twitter.com/arunmsukumar/status/603952197186035712> accessed 12 June 2015.

[29] Alina Selyukh, 'U.S. Plan To Cede Internet Domain Control On Track: ICANN Head' Reuters (2015) <http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/06/02/us-usa-internet-icann-idUSKBN0OI2IJ20150602> accessed 15 June 2015.

[30] 114th Congress, 'H.R.2251 - Defending Internet Freedom Act Of 2015' (2015).

[31] John Eggerton, 'House Bill Blocks Internet Naming Oversight Handoff: White House Opposes Legislation' Broadcasting & Cable (2015) <http://www.broadcastingcable.com/news/washington/house-bill-blocks-internet-naming-oversight-handoff/141393> accessed 9 June 2015.

[32] Communications And Technology Subcommittee Vote On The DOTCOM Act (2015).

[33] Timothy Wilt, 'DOTCOM Act Breezes Through Committee' Digital Liberty (2015) <http://www.digitalliberty.net/dotcom-act-breezes-committee-a319> accessed 22 June 2015.

The generation of e-Emergency

The article was published in Livemint on June 22, 2015.

Censorship during the Emergency in the 1970s was done by clamping down on the media by intimidating editors and journalists, and installing a human censor at every news agency with a red pencil. In the age of both multicast and broadcast media, thought and speech control is more expensive and complicated but still possible to do. What governments across the world have realized is that traditional web censorship methods such as filtering and blocking are not effective because of circumvention technologies and the Streisand effect (a phenomenon in which an attempt to hide or censor information proves to be counter-productive). New methods to manipulate the networked public sphere have evolved accordingly. India, despite claims to the contrary, still does not have the budget and technological wherewithal to successfully pull off some of the censorship and surveillance techniques described below, but thanks to Moore’s law and to the global lack of export controls on such technologies, this might change in the future.

First, mass technological-enabled surveillance resulting in self-censorship and self-policing. The coordinated monitoring of Occupy protests in the US by the Department of Homeland Security, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) counter-terrorism units, police departments and the private sector showcased the bleeding edge of surveillance technologies. Stingrays or IMSI catchers are fake mobile towers that were used to monitor calls, Internet traffic and SMSes. Footage from helicopters, drones, high-res on-ground cameras and the existing CCTV network was matched with images available on social media using facial recognition technology. This intelligence was combined with data from the global-scale Internet surveillance that we know about thanks to the National Security Agency (NSA) whistle-blower Edward Snowden, and what is dubbed “open source intelligence” gleaned by monitoring public social media activity; and then used by police during visits to intimidate activists and scare them off the protests.

Second, mass technological gaming—again, according to documents released by Snowden, the British spy agency, GCHQ (Government Communications Headquarters), has developed tools to seed false information online, cast fake votes in web polls, inflate visitor counts on sites, automatically discover content on video-hosting platform and send takedown notices, permanently disable accounts on computers, find private photographs on Facebook, monitor Skype activity in real time and harvest Skype contacts, prevent access to certain websites by using peer-to-peer based distributed denial of service attacks, spoof any email address and amplify propaganda on social media. According to The Intercept, a secret unit of GCHQ called the Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group (JTRIG) combined technology with psychology and other social sciences to “not only understand, but shape and control how online activism and discourse unfolds”. The JTRIG used fake victim blog posts, false flag operations and honey traps to discredit and manipulate activists.

Third, mass human manipulation. The exact size of the Kremlin troll army is unknown. But in an interview with Radio Liberty, St. Petersburg blogger Marat Burkhard (who spent two months working for Internet Research Agency) said, “there are about 40 rooms with about 20 people sitting in each, and each person has their assignments.” The room he worked in had each employee produce 135 comments on social media in every 12-hour shift for a monthly remuneration of 45,000 rubles. According to Burkhard, in order to bring a “feeling of authenticity”, his department was divided into teams of three—one of them would be a villain troll who would represent the voice of dissent, the other two would be the picture troll and the link troll. The picture troll would use images to counter the villain troll’s point of view by appealing to emotion while the link troll would use arguments and references to appeal to reason. In a day, the “troika” would cover 35 forums.

The next generation of censorship technology is expected to be “real-time content manipulation” through ISPs and Internet companies. We have already seen word filters where blacklisted words or phrases are automatically expunged. Last week, Bengaluru-based activist Thejesh GN detected that Airtel was injecting javascript into every web page that you download using a 3G connection. Airtel claims that it is injecting code developed by the Israeli firm Flash Networks to monitor data usage but the very same method can be used to make subtle personalized changes to web content. In China, according to a paper by Tao Zhu et al titled The Velocity of Censorship: High-Fidelity Detection of Microblog Post Deletions, “Weibo also sometimes makes it appear to a user that their post was successfully posted, but other users are not able to see the post. The poster receives no warning message in this case.”

More than two decades ago, John Gilmore, of Electronic Frontier Foundation, famously said, “the Net interprets censorship as damage and routes around it.” That was when the topology of the Internet was highly decentralized and there were hundreds of ISPs that competed with each other to provide access. Given the information diet of the average netizen today, the Internet is, for all practical purposes, highly centralized and therefore governments find it easier and easier to control.

Anti-Spam Laws in Different Jurisdictions: A Comparative Analysis

Note:- This analysis is a part of a larger attempt at formulating a model anti-spam law for India by analyzing the existing spam laws across the world.

|

CAN-SPAM Act, 2003 |

Spam Act, 2003 (Australia) |

Spam Control Act, 2007 (Singapore) |

Canada's Anti-Spam Legislation, 2014 |

The Privacy and Electronic Communications (EC Directive) Regulations, 2003 (United Kingdom) |

|

|

Jurisdiction |

National Jurisdiction. The defendant must be either an inhabitant of the United States or have a physical place of business in the US.[1] |

National Jurisdiction. Must have an "Australian link" i.e. (a) the message originates in Australia; or (b) the individual or organisation who sent the message, or authorised the sending of the message, is: (i) an individual who is physically present in Australia when the message is sent; or (ii) an organisation whose central management and control is in Australia when the message is sent; or (c) the computer, server or device that is used to access the message is located in Australia; or (d) the relevant electronic account-holder is: (i) an individual who is physically present in Australia when the message is Spam Act, 2003, § 7 Spam Control Act, 2007, § 7(2) Canada's Anti-Spam Legislation, 2014, §accessed; or (ii) an organisation that carries on business or activities in Australia when the message is accessed; or (e) if the message cannot be delivered because the relevant electronic address does not exist-assuming that the electronic address existed, it is reasonably likely that the message would have been accessed using a computer, server or device located in Australia.[2] |

National Jurisdiction. Must have a "Singapore link" An electronic message has a Singapore link in the following circumstances: (a) the message originates in Singapore; (b) the sender of the message is - (i) an individual who is physically present in Singapore when the message is sent; or (ii) an entity whose central management and control is in Singapore when the message is sent; © the computer, mobile telephone, server or device that is used to access the message is located in Singapore; the recipient of the message is- (i) an individual who is physically present in Singapore when the message is accessed; or (ii)an entity that carries on business or activities in Singapore when the message is accessed; or (e) if the message cannot be delivered because the relevant electronic address has ceased to exist (assuming that the electronic address existed), it is reasonably likely that the message would have been accessed using a computer, mobile telephone, server or device located in Singapore.[3] |