Blog

Mastering the Art of Keeping Indians Under Surveillance

The article was published in the Wire on May 30, 2015.

In a statement to the Rajya Sabha in 2009, Gurudas Kamat, the erstwhile United Progressive Alliance’s junior communications minister, said the CMS was a project to enable direct state access to all communications on mobile phones, landlines, and the Internet in India. He meant the government was building ‘backdoors’, or capitalising on existing ones, to enable state authorities to intercept any communication at will, besides collecting large amounts of metadata, without having to rely on private communications carriers.

This is not new. Legally sanctioned backdoors have existed in Europe and the USA since the early 1990s to enable direct state interception of private communications. But the laws of those countries also subject state surveillance to a strong regime of state accountability, individual freedoms, and privacy. This regime may not be completely robust, as Edward Snowden’s revelations have shown, but at least it exists on paper. The CMS is not illegal by itself, but it is coloured by the compromised foundation of Indian surveillance law upon which it is built.

Surveillance and social control

The CMS is a technological project. But technology does not exist in isolation; it is contextualised by law, society, politics, and history. Surveillance and the CMS must be seen in the same contexts.

The great sociologist Max Weber claimed the modern state could not exist without monopolising violence. It seems clear the state also entertains the equal desire to monopolise communications technologies. The state has historically shaped the way in which information is transmitted, received, and intercepted. From the telegraph and radio to telephones and the Internet, the state has constantly endeavoured to control communications technologies.

Law is the vehicle of this control. When the first telegraph line was laid down in India, its implications for social control were instantly realised; so the law swiftly responded by creating a state monopoly over the telegraph. The telegraph played a significant role in thwarting the Revolt of 1857, even as Indians attempted to destroy the line; so the state consolidated its control over the technology to obviate future contests.

This controlling impulse was exercised over radio and telephones, which are also government monopolies, and is expressed through the state’s surveillance prerogative. On the other hand, because of its open and decentralised architecture, the Internet presents the single greatest threat to the state’s communications monopoly and dilutes its ability to control society.

Interception in India

The power to intercept communications arises with the regulation of telegraphy. The first two laws governing telegraphs, in 1854 and 1860, granted the government powers to take possession of telegraphs “on the occurrence of any public emergency”. In 1876, the third telegraph law expanded this threshold to include “the interest of public safety”. These are vague phrases and their interpretation was deliberately left to the government’s discretion.

This unclear formulation was replicated in the Indian Telegraph Act of 1885, the fourth law on the subject, which is currently in force today. The 1885 law included a specific power to wiretap. Incredibly, this colonial surveillance provision survived untouched for 87 years even as countries across the world balanced their surveillance powers with democratic safeguards.

The Indian Constitution requires all deprivations of free speech to conform to any of nine grounds listed in Article 19(2). Public emergencies and public safety are not listed. So Indira Gandhi amended the wiretapping provision in 1972 to insert five grounds copied from Article 19(2). However, the original unclear language on public emergencies and public safety remained.

Indira Gandhi’s amendment was ironic because one year earlier she had overseen the enactment of the Defence and Internal Security of India Act, 1971 (DISA), which gave the government fresh powers to wiretap. These powers were not subject to even the minimal protections of the Telegraph Act. When the Emergency was imposed in 1975, Gandhi’s government bypassed her earlier amendment and, through the DISA Rules, instituted the most intensive period of surveillance in Indian history.

Although DISA was repealed, the tradition of having parallel surveillance powers for fictitious emergencies continues to flourish. Wiretapping powers are also found in the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act, 1999 which has been copied by Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, and Gujarat.

Procedural weaknesses

Meanwhile, the Telegraph Act with its 1972 amendment continued to weather criticism through the 1980s. The wiretapping power was largely exercised free of procedural safeguards such as the requirements to exhaust other less intrusive means of investigation, minimise information collection, limit the sharing of information, ensure accountability, and others.

This changed in 1996 when the Supreme Court, on a challenge brought by PUCL, ordered the government to create a minimally fair procedure. The government fell in line in 1999, and a new rule, 419A, was put into the Indian Telegraph Rules, 1951.

Unlike the United States, where a wiretap can only be ordered by a judge when she decides the state has legally made its case for the requested interception, an Indian wiretap is sanctioned by a bureaucrat or police officer. Unlike the United Kingdom, which also grants wiretapping powers to bureaucrats but subjects them to two additional safeguards including an independent auditor and a judicial tribunal, an Indian wiretap is only reviewed by a committee of the original bureaucrat’s colleagues. Unlike most of the world which restricts this power to grave crime or serious security needs, an Indian wiretap can even be obtained by the income tax department.

Rule 419A certainly creates procedure, but it lacks crucial safeguards that impugn its credibility. Worse, the contours of rule 419A were copied in 2009 to create flawed procedures to intercept the content of Internet communications and collect metadata. Unlike rule 419A, these new rules issued under sections 69(2) and 69B(3) of the Information Technology Act 2000 have not been constitutionally scrutinised.

Three steps to tap

Despite its monopoly, the state does not own the infrastructure of telephones. It is dependent on telecommunications carriers to physically perform the wiretap. Indian wiretaps take place in three steps: a bureaucrat authorises the wiretap; a law enforcement officer serves the authorisation on a carrier; and, the carrier performs the tap and returns the information to the law enforcement officer.

There are many moving parts in this process, and so there are leaks. Some leaks are cynically motivated such as Amar Singh’s lewd conversations in 2011. But others serve a public purpose: Niira Radia’s conversations were allegedly leaked by a whistleblower to reveal serious governmental culpability. Ironically, leaks have created accountability where the law has failed.

The CMS will prevent leaks by installing servers on the transmission infrastructure of carriers to divert communications to regional monitoring centres. Regional centres, in turn, will relay communications to a centralised monitoring centre where they will be analysed, mined, and stored. Carriers will no longer perform wiretaps; and, since this obviates their costs of compliance, they are willing participants.

In its annual report of 2012, the Centre for the Development of Telematics (C-DOT), a state-owned R&D centre tasked with designing and creating the CMS, claimed the system would intercept 3G video, ILD, SMS, and ISDN PRI communications made through landlines or mobile phones – both GSM and CDMA.

There are unclear reports of an expansion to intercept Internet data, such as emails and browsing details, as well as instant messaging services; but these remain unconfirmed. There is also a potential overlap with another secretive Internet surveillance programme being developed by the Defence R&D Organisation called NETRA, no details of which are public.

Culmination of surveillance

In its present state, Indian surveillance law is unable to bear the weight of the CMS project, and must be vastly strengthened to protect privacy and accountability before the state is given direct access to communications.

But there is a larger way to understand the CMS in the context of Indian surveillance. Christopher Bayly, the noted colonial historian, writes that when the British set about establishing a surveillance apparatus in colonised India, they came up against an established system of indigenous intelligence gathering. Colonial rule was at its most vulnerable at this point of intersection between foreign surveillance and indigenous knowledge, and the meeting of the two was riven by suspicion. So the colonial state simply co-opted the interface by creating institutions to acquire local knowledge.

The CMS is also an attempt to co-opt the interface between government and the purveyors of communications; because if the state cannot control communications, it cannot control society. Seen in this light, the CMS represents the natural culmination of the progression of Indian surveillance. No challenge against it that does not question the construction of the modern Indian state will be successful.

The Four Parts of Privacy in India

Traditionally traced to classical liberalism’s public/private divide, there are now several theoretical conceptions of privacy that collaborate and sometimes contend. Indian privacy law is evolving in response to four types of privacy claims: against the press, against state surveillance, for decisional autonomy, and in relation to personal information. The Indian Supreme Court has selectively borrowed competing foreign privacy norms, primarily American, to create an unconvincing pastiche of privacy law in India. These developments are undermined by a lack of theoretical clarity and the continuing tension between individual freedoms and communitarian values.

This was published in Economic & Political Weekly, 50(22), 30 May 2015. Download the full article here.

The Four Parts of Privacy in India

Acharya - The Four Parts of Privacy in India (EPW Insight).pdf

—

PDF document,

610 kB (625400 bytes)

Acharya - The Four Parts of Privacy in India (EPW Insight).pdf

—

PDF document,

610 kB (625400 bytes)

Multi-stakeholder Advisory Group Analysis

The researcher has collected the data from the lists of members available in the public domain from 2010-2015. The lists prior to 2010 have been procured by the Centre for Internet and society from the UN Secretariat of the Internet Governance Forum (IGF).

This research is based solely upon the members and the nature of their stake holding has been analysed in the light of MAG terms of reference. No data has been made available regarding the nomination process and the criteria on which a particular member has been re-elected to the MAG (The IGF Secretariat does not share this data).

According to the analysis, in these six years, the MAG has had around 182 members from various stakeholder groups.

We have divided it into five stakeholder groups, Government, Civil Society, Industry, Technical Community and Academia. Any overlap between two or more of these groups has also been taken into account, for example- A member of the Internet Society (ISOC) being both in the Civil Society and Technical Community.

According to the MAG Terms of Reference[1], it is the prerogative of the UN Secretary General to select MAG Members. The general policy is that the MAG members are appointed for a period of one year, which is automatically renewed for 2 more years consecutively depending on their engagement in MAG activities.

There is also a policy of rotating off 1/3rd members of MAG every year for diversity and taking new viewpoints in consideration. There is also an exceptional circumstance where a person might continue beyond three years in case there is a lack of candidates fitting the desired area.

However, it seems like the exception has become the norm as a whopping number of members have continued beyond 3 years, ranging from 4 years up to as long as 8 years, this figure rounds up to around 49. No doubt some of them are exceptional talents and difficult to replace. However, the lack of transparency in the nomination system makes it difficult to determine the basis on which these people continued beyond the usual term.

|

S. No. |

Stakeholder |

Number of years |

Total Members continuing beyond 3 years |

|

1 |

Civil Society |

8, 6, 6, 4, 4, |

5 |

|

2 |

Government/Industry |

4, 5 |

2 |

|

3 |

Technical community/ Civil society |

8, 8, 8, 6, 6, 4, 4, 4, 4,4 |

10 |

|

4 |

Industry/ Civil society |

8, 6, |

2 |

|

5 |

Industry |

8, 7, 7, 6, 6, 4, |

6 |

|

6 |

Industry/Tech Community/ Civil Society |

8, |

1 |

|

7 |

Government |

7, 7, 7, 6, 6, 6, 6, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, 4, |

19 |

|

8 |

Academia |

6, 6, 5, |

3 |

|

9 |

Industry/ Tech community |

6, |

1 |

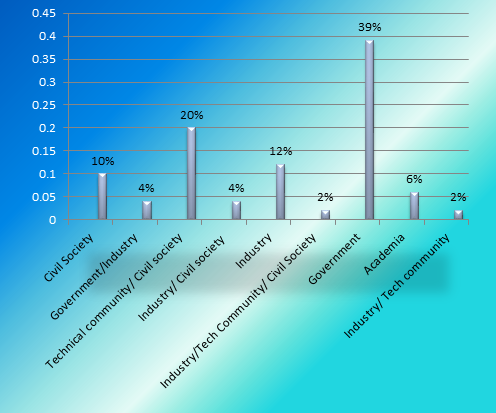

The stakeholders that have continued beyond 8 years have around 39% members from Government and related agencies. The next being Technical Community/Civil Society with around 20% representation, followed by Industry at 12%, 10% from the Civil Society, 6% from Academia, 4% from Government/Industry, 4% from Industry/Civil Society and 2% each from Industry/Technical Community and Industry/Technical Community/Civil Society respectively.

|

|

|---|

Table with overlapping interests merged

|

S. No. |

Stakeholder |

Total Members continuing beyond 3 years |

|

1 |

Civil Society |

7 + 9 + 1+1 = 18 |

|

2 |

Government |

19 |

|

3 |

Tech Community |

9 + 1 + 1+1 = 12 |

|

4 |

Industry |

6 + 2 + 1 + 1+2 = 13 |

|

5 |

Academia |

3 |

When the overlap is grouped separately, as in if a Technical Community/Civil Society person is placed both in Technical Community and Civil Society groups individually, then the representation of stakeholder representation is as follows(approximate values)-

Government- 29%

Civil Society- 28%

Industry- 20%

Technical Community-17%

Academia-5%

This clearly shows us that stakeholders from academia generally did not stay on MAG beyond 3 years. Even when all members that have ever been on MAG are taken into consideration, only around 8% representation has been from the academic community. This needs to be taken into account when new MAG members are selected in 2016.

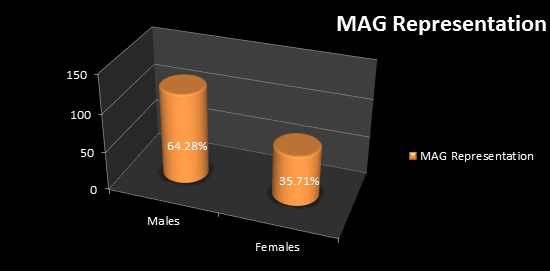

The researcher has also looked at the MAG Representation based on gender and UN Regional Groups. The results of the analysis were as follows-

The ratio of male members is to female members is approximately 16:9 in the MAG and the approximate value in percentage being 64% and 36% respectively.

|

|

|---|

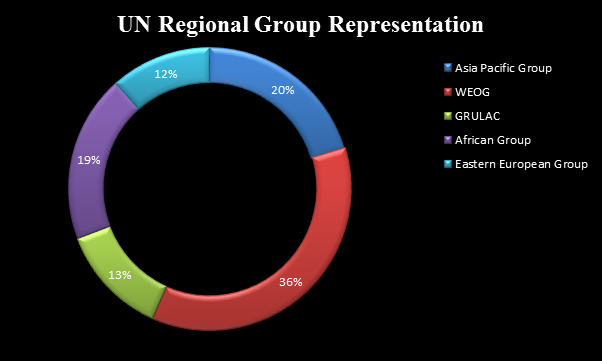

Now coming to the UN Regional Groups, the results that the analysis yielded were as follows-

The Western European and Others Group (WEOG) has the highest representation in MAG, a large number of members being from Switzerland, USA and UK. This is followed by the Asia Pacific Group which has 20% representation. The third largest is the African group with 19% representation followed by Latin American and Caribbean Group (GRULAC) and Eastern European Group with 13% and 12% representation respectively.

|

|---|

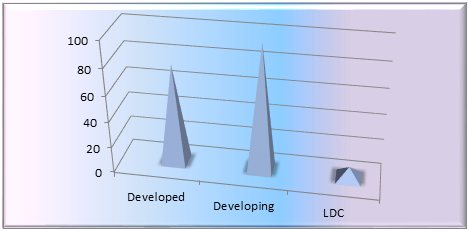

The representation of developed, developing and Least Developed Countries is as follows-

Developed countries have approximately 42% representation, developing countries having 53% and LDCs having a mere 5% representation. There should be some effort to strive for better LDC representation as they are the most backward when it comes to Global ICT Penetration. [2]

[1] Intgovforum.org, 'MAG Terms Of Reference' (2015) <http://www.intgovforum.org/cms/175-igf-2015/2041-mag-terms-of-reference> accessed 13 July 2015.

[2] ICT Facts And Figures (1st edn, International Telecommunication Union 2015) <http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Documents/facts/ICTFactsFigures2015.pdf> accessed 11 July 2015.

Supreme Court Order is a Good Start, but is Seeding Necessary?

Introduction

On August 11th 2015, in the writ petition Justice K.S Puttaswamy (Retd.) & Another vs. Union of India & Others1, the Supreme Court of India issued an interim order regarding the constitutionality of the UIDAI scheme. In response to the order, Dr. Usha Ramanathan published an article titled 'Decoding the Aadhaar judgment: No more seeding, not till the privacy issue is settled by the court' which, among other points, highlights concerns around the seeding of Aadhaar numbers into service delivery databases. She writes that "seeding' is a matter of grave concern in the UID project. This is about the introduction of the number into every data base. Once the number is seeded in various databases, it makes convergence of personal information remarkably simple. So, if the number is in the gas agency, the bank, the ticket, the ration card, the voter ID, the medical records and so on, the state, as also others who learn to use what is called the 'ID platform', can 'see' the citizen at will."2

Building off of this statement, this article seeks to unpack the 'seeding' process in the UIDAI scheme, understand the implications of the Supreme Court order on this process, and identify questions regarding the UID scheme that still need to be clarified by the Court in the context of the seeding process.

What is Seeding?

In the UID scheme, data points within databases of service providers and banks are organized via individual Aadhaar numbers through a process known as 'seeding'. The UIDAI has released two documents on the seeding process - "Approach Document for Aadhaar Seeding in Service Delivery Databases version 1.0" (Version 1.0)3 and "Standard Protocol Covering the Approach & Process for Seeding Aadhaar Number in Service Delivery Databases June 2015 Version 1.1" (Version 1.1)4

According to Version 1.0 "Aadhaar seeding is a process by which UIDs of residents are included in the service delivery database of service providers for enabling Aadhaar based authentication during service delivery."5 Version 1.0 further states that the "Seeding process typically involves data extraction, consolidation, normalization, and matching".6 According to Version 1.1, Aadhaar seeding is "a process by which the Aadhaar numbers of residents are included in the service delivery database of service providers for enabling de-duplication of database and Aadhaar based authentication during service delivery".7 There is an extra clause in Version 1.1's definition of seeding which includes "de-duplication" in addition to authentication.

Though not directly stated, it is envisioned that the Aadhaar number will be seeded into the databases of service providers and banks to enable cash transfers of funds. This was alluded to in the Version 1.1 document with the UIDAI stating "Irrespective of the Scheme and the geography, as the Aadhaar Number of a given Beneficiary finally has to be linked with the Bank Account, Banks play a strategic and key role in Seeding."8

How does the seeding process work?

The seeding process itself can be done through manual/organic processes or algorithmic/in-organic processes. In the inorganic process the Aadhaar database is matched with the database of the service provider - namely the database of beneficiaries, KYR+ data from enrolment agencies, and the EID-UID database from the UIDAI. Once compared and a match is found - for example between KYR fields in the service delivery database and KYR+ fields in the Aadhaar database - the Aadhaar number is seeded into the service delivery database.9

Organic seeding can be carried out via a number of methods, but the recommended method from the UIDAI is door to door collection of Aadhaar numbers from residents which are subsequently uploaded into the service delivery database either manually or through the use of a tablet or smart phone. Perhaps demonstrating the fact that technology cannot be used as a 'patch' for a broken or premature system, organic (manual) seeding is suggested as the preferred process by the UIDAI due to challenges such as lack of digitization of beneficiary records, lack of standardization in Name and Address records, and incomplete data.10

According to the 1.0 Approach Paper, to facilitate the seeding process, the UIDAI has developed an in house software known as Ginger. Service providers that adopt the Aadhaar number must move their existing databases onto the Ginger platform, which then organizes the present and incoming data in the database by individual Aadhaar numbers. This 'organization' can be done automatically or manually. Once organized, data can be queried by Aadhaar number by person's on the 'control' end of the Ginger platform.11

In practice this means that during an authentication in which the UIDAI responds to a service provider with a 'yes' or 'no' response, the UIDAI would have access to at least these two sets of data: 1.) Transaction data (date, time, device number, and Aadhaar number of the individual authenticating) 2.) Data associated to an individual Aadhaar number within a database that has been seeded with Aadhaar numbers (historical and incoming). According to the Approach Document version 1.0, "The objective here is that the seeding process/utility should be able to access the service delivery data and all related information in at least the read-only mode." 12 and the Version 1.1 document states "Software application users with authorized access should be able to access data online in a seamless fashion while providing service benefit to residents." 13

What are the concerns with seeding?

With the increased availability of data analysis and processing technologies, organisations have the ability to link disparate data points stored across databases in order that the data can be related to each other and thereby analysed to derive holistic, intrinsic, and/or latent assessments. This can allow for deeper and more useful insights from otherwise standalone data. In the context of the government linking data, such "relating" can be useful - enabling the government to visualize a holistic and more accurate data and to develop data informed policies through research14. Yet, allowing for disparate data points to be merged and linked to each other raises questions about privacy and civil liberties - as well as more intrinsic questions about purpose, access, consent and choice. To name a few, linked data can be used to create profiles of individuals, it can facilitate surveillance, it can enable new and unintended uses of data, and it can be used for discriminatory purposes.

The fact that the seeding process is meant to facilitate extraction, consolidation, normalization and matching of data so it can be queried by Aadhaar number, and that existing databases can be transposed onto the Ginger platform can give rise to Dr. Ramanthan's concerns. She argues that anyone having access to the 'control' end of the Ginger platform can access all data associated to a Aadhaar number, that convergence can now easily be initiated with databases on the Ginger platform, and that profiling of individuals can take place through the linking of data points via the Ginger platform.

How does the Supreme Court Order impact the seeding process and what still needs to be clarified?

In the interim order the Supreme Court lays out four welcome clarifications and limitations on the UID scheme:

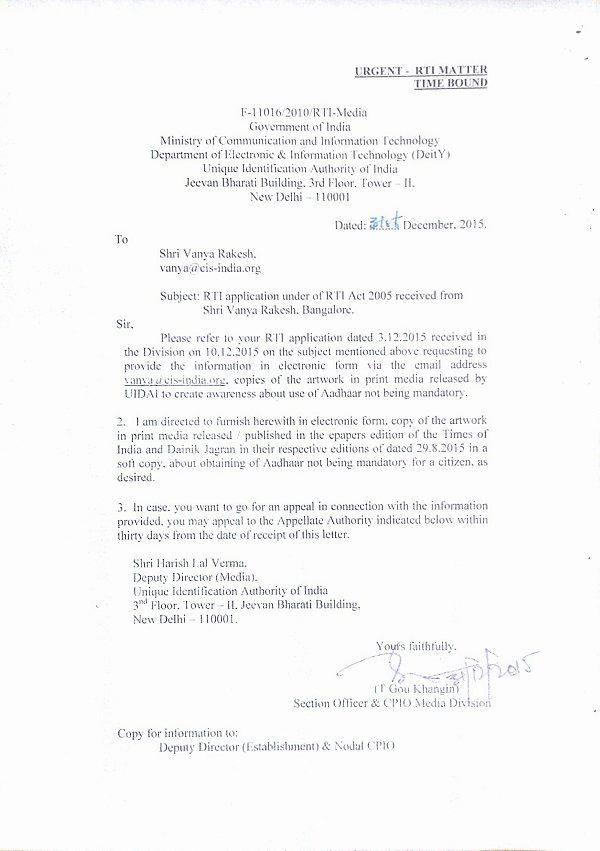

- The Union of India shall give wide publicity in the electronic and print media including radio and television networks that it is not mandatory for a citizen to obtain an Aadhaar card;

- The production of an Aadhaar card will not be condition for obtaining any benefits otherwise due to a citizen;

- The Unique Identification Number or the Aadhaar card will not be used by the respondents for any purpose other than the PDS Scheme and in particular for the purpose of distribution of foodgrains, etc. and cooking fuel, such as kerosene. The Aadhaar card may also be used for the purpose of the LPG Distribution Scheme;

- The information about an individual obtained by the Unique Identification Authority of India while issuing an Aadhaar card shall not be used for any other purpose, save as above, except as may be directed by a Court for the purpose of criminal investigation."15

In some ways, the court order addresses some of the concerns regarding the seeding of Aadhaar numbers by limiting the scope of the seeding process to the PDS scheme, but there are still a number of aspects of the scheme as they pertain to the seeding process that need to be addressed by the court.

These include:

The Process of Seeding

Prior to the Supreme Court interim order, the above concerns were quite broad in scope as Aadhaar could be adopted by any private or public entity - and the number was being seeded in databases of banks, the railways, tax authorities, etc. The interim order, to an extent, lessens these concerns by holding that "The Unique Identification Number or the Aadhaar card will not be used by the respondents for any purpose other than the PDS Scheme…".

However, the Court could have perhaps been more specific regarding what is included under the PDS scheme, because the scheme itself is broad. That said, the restrictions put in place by the court create a form of purpose limitation and a boundary of proportionality on the UID scheme. By limiting the purpose of the Aadhaar number to use in the PDS system, the Aadhaar number can only be seeded into the databases of entities involved in the PDS Scheme, rather than any entity that had adopted the number. Despite this, the seeding process is an issue in itself for the following reasons:

Consent: Upon enrolling for an Aadhaar number, individuals have the option of consenting to the UIDAI sharing information in three instances:

- "I have no objection to the UIDAI sharing information provided by me to the UIDAI with agencies engaged in delivery of welfare services."

- "I want the UIDAI to facilitate opening of a new Bank/Post Office Account linked to my Aadhaar Number.

- "I have no objection to sharing my information for this purpose""I have no objection to linking my present bank account provided here to my Aadhaar number"17

Withdrawing Consent: The Court also did not directly address if individuals could withdraw consent after enrolling in the UID scheme - and if they did - whether Aadhaar numbers should be 'unseeded' from PDS related databases. Similarly, the Court did not clarify whether services that have seeded the Aadhaar number, but are not PDS related, now need to unseed the number. Though news items indicate that in some cases (not all) organizations and government departments not involved in the PDS system are stopping the seeding process19, there is no indication of departments undertaking an 'unseeding' process. Nor is there any indication of the UIDAI allowing indivduals enrolled to 'un-enroll' from the scheme. In being silent on issues around consent, the court order inadvertently overlooks the risk of function creep possible through the seeding process, which "allows numerous opportunities for expansion of functions far beyond those stated to be its purpose"20.

Verification and liability: According to Version 1.0 and Version 1.1 of the Seeding documents, "no seeding is better than incorrect seeding". This is because incorrect seeding can lead to inaccuracies in the authentication process and result in individuals entitled to benefits being denied such benefits. To avoid errors in the seeding process the UIDAI has suggested several steps including using the "Aadhaar Verification Service" which verifies an Aadhaar number submitted for seeding against the Aadhaar number and demographic data such as gender and location in the CIDR. Though recognizing the importance of accuracy in the seeding process, the UIDAI takes no responsibility for the same. According to Version 1.1 of the seeding document, "the responsibility of correct seeding shall always stay with the department, who is the owner of the database."21 This replicates a disturbing trend in the implementation of the UID scheme - where the UIDAI 'initiates' different processes through private sector companies but does not take responsibility for such processes. 22

The Scope of the UIDAI's mandate and the necessity of seeding

Aside from the problems within the seeding process itself, there is a question of the scope of the UIDAI's mandate and the role that seeding plays in fulfilling this. This is important in understanding the necessity of the seeding process.

On the official website, the UIDAI has stated that its mandate is "to issue every resident a unique identification number linked to the resident's demographic and biometric information, which they can use to identify themselves anywhere in India, and to access a host of benefits and services." 23 Though the Supreme Court order clarifies the use of the Aadhaar number, it does not address the actual legality of the UIDAI's mandate - as there is no enabling statute in place -and it does not clarify or confirm the scope of the UIDAI's mandate.

In Version 1.0 of the Seeding document the UIDAI has stated the "Aadhaar numbers of enrolled residents are being 'seeded' ie. included in the databases of service providers that have adopted the Aadhaar platform in order to enable authentication via the Aadhaar number during a transaction or service delivery."24 This statement is only partially correct. For only providing and authenticating of an Aadhaar number - seeding is not necessary as the Aadhaar number submitted for verification alone only needs to be compared with the records in the CIDR to complete authentication of the same. Yet, in an example justifying the need for seeding in the Version 1.0 seeding document the UIDAI states "A consolidated view of the entire data would facilitate the social welfare department of the state to improve the service delivery in their programs, while also being able to ensure that the same person is not availing double benefits from two different districts."25 For this purpose, seeding is again unnecessary as it would be simple to correlate PDS usage with a Aadhaar number within the PDS database. Even if limited to the PDS system, seeding in the databases of service providers is only necessary for the creation and access to comprehensive information about an individual in order to determine eligibility for a service. Further, seeding is only necessary in the databases of banks if the Aadhaar number moves from being an identity factor - to a transactional factor - something that the UIDAI seems to envision as the Version 1.1 seeding document states that Aadhaar is sufficient enough to transfer payments to an individual and thus plays a key role in cash transfers of benefits.26

Conclusion

Despite the fact that adherence to the interim order from the Supreme Court has been adhoc27, the order does provide a number of welcome limitations and clarifications to the UID Scheme. Yet, despite limited clarification from the Supreme Court and further clarification from the Finance Ministry's Order, the process of seeding and its necessity remain unclear. Is the UIDAI taking fully informed consent for the seeding process and what it will enable? Should the UIDAI be liable for the accuracy of the seeding process? Is seeding of service provider and bank databases necessary for the UIDAI to fulfill its mandate? Is the UIDAI's mandate to provide an identifier and an authentication of identity mechanism or is it to provide authentication of eligibility of an individual to receive services? Is this mandate backed by law and with adequate safeguards? Can the court order be interpreted to mean that to deliver services in the PDS system, UIDAI will need access to bank accounts or other transactions/information stored in a service provider's database to verify the claims of the user?

Many news items reflect a concern of convergence arising out of the UID scheme.28 To be clear, the process of seeding is not the same as convergence. Seeding enables convergence which can enable profiling, surveillance, etc. That said, the seeding process needs to be examined more closely by the public and the court to ensure that society can reap the benefits of seeding while avoiding the problems it may pose.

[1]. Justice K.S Puttaswamy & Another vs. Union of India & Others. Writ Petition (Civil) No. 494 of 2012. Available at: http://judis.nic.in/supremecourt/imgs1.aspx?filename=42841

[2]. Usha Ramanthan. Decoding the Aadhaar judgment: No more seeding, not till the privacy issues is settled by the court. The Indian Express. August 12th 2015. Available at: http://indianexpress.com/article/blogs/decoding-the-aadhar-judgment-no-more-seeding-not-till-the-privacy-issue-is-settled-by-the-court/

[3]. UIDAI. Approach Document for Aadhaar Seeding in Service Delivery Databases. Version 1.0. Available at: https://authportal.uidai.gov.in/static/aadhaar_seeding_v_10_280312.pdf

[4]. UIDAI. Standard Protocol Covering the Approach & Process for Seeding Aadhaar Numbers in Service Delivery Databases. Available at: https://uidai.gov.in/images/aadhaar_seeding_june_2015_v1.1.pdf

[5]. Version 1.0 pg. 2

[6]. Version 1.0 pg. 19

[7]. Version 1.1 pg. 3

[8]. Version 1.1 pg. 7

[9]. Version 1.1 pg. 5 -7

[10]. Version 1.1 pg. 7-13

[11]. Version 1.0 pg 19-22

[12]. Version 1.0 pg. 4

[13]. Version 1.1 pg. 5, figure 3.

[14]. David Card, Raj Chett, Martin Feldstein, and Emmanuel Saez. Expanding Access to Adminstrative Data for Research in the United States. Available at: http://obs.rc.fas.harvard.edu/chetty/NSFdataaccess.pdf

[15]. Justice K.S Puttaswamy & Another vs. Union of India & Others. Writ Petition (Civil) No. 494 of 2012. Available at: http://judis.nic.in/supremecourt/imgs1.aspx?filename=42841

[16]. Version 1.1 pg. 18

[17]. Aadhaar Enrollment Form from Karnataka State. http://www.karnataka.gov.in/aadhaar/Downloads/Application%20form%20-%20English.pdf

[18]. Business Line. Aadhaar only for foodgrains, LPG, kerosene, distribution. August 27th 2015. Available at: http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/aadhaar-only-for-foodgrains-lpg-kerosene-distribution/article7587382.ece

[19]. Bharti Jain. Election Commission not to link poll rolls to Aadhaar. The Times of India. August 15th 2015. Available at: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Election-Commission-not-to-link-poll-rolls-to-Aadhaar/articleshow/48488648.cms

[20]. Graham Greenleaf. “Access all areas': Function creep guaranteed in Australia's ID Card Bill (No.1) Computer Law & Security Review. Volume 23, Issue 4. 2007. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0267364907000544

[21]. Version 1.1 pg. 3

[22]. For example, the UIDAI depends on private companies to act as enrollment agencies and collect, verify, and enroll individuals in the UID scheme. Though the UID enters into MOUs with these organizations, the UID cannot be held responsible for the security or accuracy of data collected, stored, etc. by these entities. See draft MOU for registrars: https://uidai.gov.in/images/training/MoU_with_the_State_Governments_version.pdf

[23]. Justice K.S Puttaswamy & Another vs. Union of India & Others. Writ Petition (Civil) No. 494 of 2012. Available at: http://judis.nic.in/supremecourt/imgs1.aspx?filename=42841

[24]. Version 1.0 pg.3

[25]. Version 1.0 pg.4

[26]. Version 1.1 pg. 3

[27]. For example, there are reports of Aadhaar being introduced for different services such as education. See: Tanu Kulkarni. Aadhaar may soon replace roll numbers. The Hindu. August 21st, 2015. For example: http://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/bangalore/aadhaar-may-soon-replace-roll-numbers/article7563708.ece

[28]. For example see: Salil Tripathi. A dangerous convergence. July 31st. 2015. The Live Mint. Available at: http://www.livemint.com/Opinion/xrqO4wBzpPbeA4nPruPNXP/A-dangerous-convergence.html

Are we Throwing our Data Protection Regimes under the Bus?

Consent is complicated. What we think of as reasonably obtained consent varies substantially with the circumstance. For example, in treating rape cases, the UK justice system has moved to recognise complications like alcohol and its effect on explicit consent[1]. Yet in contracts, consent may be implied simply when one person accepts another’s work on a contract without objections[2]. These situations highlight the differences between the various forms of informed consent and the implications on its validity.

Consent has emerged as a key principle in regulating the use of personal data, and different countries have adopted different regimes, ranging from the comprehensive regimes like of the EU to more sectoral approaches like that in the USA. However, in our modern epoch characterised by the big data analytics that are now commonplace, many commentators have challenged the efficacy and relevance of consent in data protection. I argue that we may even risk throwing our data protection regimes under the proverbial bus should we continue to focus on consent as a key pillar of data protection.

Consent as a tool in Data Protection Regimes

In fact, even a cursory review of current data protection laws around the world shows the extent of the law’s reliance on consent. In the EU for example, Article 7 of the Data Protection Directive, passed in 1995, provides that data processing is only legitimate when “the data subject has unambiguously given his consent”[3]. Article 8, which guards against processing of sensitive data, provides that such prohibitions may be lifted when “the data subject has given his explicit consent to the processing of those data”[4]. Even as the EU attempts to strengthen data protection within the bloc with the proposed reforms to data protection[5], the focus on the consent of data subject remains strong. There are proposals for an “unambiguous consent by the data subject”[6] requirement to be put in place. Such consent will be mandatory before any data processing can occur[7].

Despite adopting very different overall approaches to data protection and privacy, consent is an equally integral part of data protection frameworks in the USA. In his book Protectors of Privacy[8], Abraham Newman describes two main types of privacy legislation: comprehensive and limited. He argues that places like the EU have adopted comprehensive regimes, which primarily seek to protect individuals because of the “informational and power asymmetry” between individuals and organisations[9]. On the other hand, he classifies the American approach as limited, focusing on more sectoral protections and principles of fair information practice instead of overarching legislation[10]. These sectors include the Fair Credit Reporting Act[11] (which governs consumer credit reporting), the Privacy Act[12] (which governs data collected by Federal government) and Electronic Communications Privacy Act[13] (which deals with email communications) among others. However, the Federal Trade Commission describes itself as having only “limited authority over the collection and dissemination of personal data collected online”[14].

This is because the general data processing that is commonplace in today’s era of big data is only regulated by the privacy protections that come from the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs). Expectedly, consent is equally important under the FTC’s FIPPs. The FTC describes the principle of consent as “the second widely-accepted core principle of fair information practice”[15] in addition to the principle of notice. Other guidelines on fair data processing published by organisations like the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development[16] (OECD) or Canadian Standards Association[17] (CSA) also include consent as a key mechanism in data protection.

The origins of consent in privacy and data protection

Given the clearly extensive reliance on consent in data protection, it seems prudent to examine the origins of consent in privacy and data protection. Just why does consent have so much weight in data protection?

One reason is that data protection, along with inextricably linked concerns about privacy, could be said to be rooted in protecting private property. It was argued that the “early parameters of what was to become the right to privacy were set in cases dealing with unconventional property claims”[18], such as unconsented publication of personal letters[19] or photographs[20]. It was the publication of Brandeis and Warren’s well-known article “The Right to Privacy”[21], that developed “the current philosophical dichotomy between privacy and property rights”[22], as they asserted that privacy protections ought to be recognised as a right in and of themselves and needed separate protection[23]. Indeed, it was Warren and Brandeis who famously borrowed Justice Cooley's expression that privacy is the “right to be let alone”[24].

On the other side of the debate are scholars like Epstein and Posner, who see privacy protections as part of protecting personal property under tort law[25]. However, the central point is that most scholars seem to acknowledge the relationship between privacy and private property. Even Brandeis and Warren themselves argued that one general aim of privacy is “to protect the privacy of private life, and to whatever degree and in whatever connection a man's life has ceased to be private”[26].

It is also important to locate the idea of consent within the domain of privacy and private property protections. Ostensibly, consent seems to have the effect of lessening the privacy protections afforded in a particular situation to a person, because by acquiescing to the situation, one could be seen as waiving their privacy concerns. Brandeis and Warren concur with this position as they acknowledge how “the right to privacy ceases upon the publication of the facts by the individual, or with his consent”[27]. They assert that this is “but another application of the rule which has become familiar in the law of literary and artistic property”[28].

Perhaps the most eloquent articulation of the importance of consent in privacy comes from Sir Edward Coke’s idea that “every man’s house is his castle”[29]. Though the ‘Castle Doctrine’ has been used as a justification for protecting one’s property with the use of force[30], I think that implied in the idea of the ‘Castle Doctrine’ is that consent is necessary in order to preserve privacy. If not, why would anyone be justified in preventing trespass, other than to prevent unconsented entry or use of their property. The doctrine of “Volenti non fit injuria”[31], or ‘to one who consents no injury is done’, is thus the very embodiment of the role of consent in protecting private property. And as conceptions of private property develop to recognise that the data one gives out is part of his private property, for example in US v. Jones, which led scholars to assert that “people should be able to maintain reasonable expectations of privacy in some information voluntarily disclosed to third parties”[32], so does consent act as an important aspect of privacy protection.

Yet, linking privacy with private property is not universally accepted as the conception of privacy. For instance, Alan Westin, in his book Privacy and Freedom[33], describes privacy as “the right to control information about oneself”[34]. Another scholar, Ruth Gavison, contends instead that “our interest in privacy is related to our concern over our accessibility to others: the extent to which we are known to others, the extent to which others have physical access to us, and the extent to which we are the subject of others' attention”[35].

While these alternative notions about privacy’s foundational principles may differ from those related to linking privacy with private property, locating consent within these formulations of privacy is possible. Regarding Westin’s argument, I think that implicit in the right to control one’s information are ideas about individual autonomy, which is exercised through giving or withholding one’s consent. Similarly, Gavison herself states that privacy functions to advance “liberty, autonomy and selfhood”[36]. Consent plays a key role in upholding this liberty, autonomy and selfhood that privacy affords us. Clearly therefore, it is far from unfounded to claim that consent is an integral part of protecting privacy.

Consent, Big Data and Data protection

Given the solid underpinnings of the principle of consent in privacy protection, it was hardly a coincidence that consent became an integral part of data protection. However, with the rise of big data practices, one quickly finds that consent ceases to work effectively as a tool for protecting privacy. In a big data context, Solove argues that privacy regulation rooted in consent is ineffective, because garnering consent amidst ubiquitous data collection for all the online services one uses as part of daily life is unmanageable[37]. Additionally, the secondary uses of one’s data are difficult to assess at the point of collection, and subsequently meaningful consent for secondary use is difficult to obtain[38]. This section examines these two primary consequences of prioritising consent amidst Big data practises.

Consent places unrealistic and unfair expectations on the Individual

As noted by Tene and Polonetsky, the first concern is that current privacy frameworks which emphasize informed consent “impose significant, sometimes unrealistic, obligations on both organizations and individuals”[39]. The premise behind this argument stems from the way that consent is often garnered by organisations, especially regarding use of their services. An examination of various terms of use policies from banks, online video streaming websites, social networking sites, online fashion or more general online shopping websites reveals a deluge of information that the user has to comprehend. Moreover, there are a too many “entities collecting and using personal data to make it feasible for people to manage their privacy separately with each entity”[40].

As Cate and Mayer-Schönberger note in the Microsoft Global Privacy Summit Summary Report, “almost everywhere that individuals venture, especially online, they are presented with long and complex privacy notices routinely written by lawyers for lawyers, and then requested to either “consent” or abandon the use of the desired service”[41]. In some cases, organisations try to simplify these policies for the users of their service, but such initiatives make up the minority of terms of use policies. Tene and Polonetsky assert that “it is common knowledge among practitioners in the field that privacy policies serve more as liability disclaimers for businesses than as assurances of privacy for consumers”[42].

However, it is equally important to consider the principle of consent from perspective of companies. At a time where many businesses have to comply with numerous regulations and processes in the name of ‘compliance’[43], the obligations for obtaining consent could burden some businesses. Firms have to gather consent amidst enhancing user or customer experiences, which represents a tricky balance to find. For example, requiring consent at every stage may make the user experience much worse. Imagine having to give consent for your profile to be uploaded every time you make a high score in a video game? At the same time, “organizations are expected to explain their data processing activities on increasingly small screens and obtain consent from often-uninterested individuals”[44]. Given these factors, it is somewhat understandable for companies to garner consent for all possible (secondary) uses as otherwise it is not feasible to keep collecting.

Nonetheless, this results in situations where “data processors can perhaps too easily point to the formality of notice and consent and thereby abrogate much of their responsibility”[45].The totality of the situation shows the odds stacked against the individual. It could be even argued that this is one manifestation of the informational and power asymmetry that exists between individuals and organisations[46], because users may unwittingly agree to unfair, unclear or even unknown terms and conditions and data practices. Not only are individuals greatly misinformed about data collected about them, but the vast majority of people do not even read these Terms and Conditions or End User license agreements[47]. Solove also argues that “people often lack enough expertise to adequately assess the consequences of agreeing to certain present uses or disclosures of their data”[48].

While the organisational practice of providing extensive and complicated terms of use policies is not illegal, the fact that by one estimation, it may take you would have to take 76 working days to review the privacy policies you have agreed to online[49], or by another, that in the USA the opportunity cost society incurs in reading privacy policies is $781 billion[50], should not go unnoticed. I do think it is unfair for the law to put users into such situations, where they are “forced to make overly complex decisions based on limited information”[51]. There have been laudable attempts by some government organisations like Canada’s Office of the Privacy Commissioner and USA’s Federal Trade Commission to provide guidance to firms to make their privacy policies more accessible[52]. However, these are hard to enforce. Therefore, it can be assumed that when users have neither the expertise nor the rigour to review privacy policies effectively, the consent they provide would naturally be far from informed.

Secondary use, Aggregation and Superficial Consent

What amplifies this informational asymmetry is the potential for the aggregation of individual’s data and subsequent secondary use of that data collected. “Even if people made rational decisions about sharing individual pieces of data in isolation, they greatly struggle to factor in how their data might be aggregated in the future”[53].

This has to do with the prevalence of big data analytics that characterizes our modern epoch, and has major implications for the nature and meaningfulness of the consent users provide. By definition, “big data analysis seeks surprising correlations”[54] and some of its most insightful results are counterintuitive and nearly impossible to conceive at the point of primary data collection. One noteworthy example comes from the USA, with the predictive analytics of Walmart. By studying purchasing patterns of its loyalty card holders[55], the company ascertained that prior to a hurricane the most popular items that people tend to buy are actually Pop Tarts (a pre-baked toaster pastry) and Beer[56]. These correlations are highly counterintuitive and far from what people expect to be necessities before a hurricane. These insights led to Walmart stores being stocked with the most relevant products at the time of need. This is one example of how data might be repurposed and aggregated for a novel purpose, but nonetheless the question about the nature of consent obtained by Walmart for the collection and analysis of the shopping habits of its loyalty card holders stands.

One reason secondary uses make consent less meaningful has been articulated by De Zwart et al, who observe that “the idea of consent becomes unworkable in an environment where it is not known, even by the people collecting and selling data, what will happen to the data”[57]. Taken together with Solove’s aggregation effect, two points become apparent:

- Data we consent to be collected about us may be aggregated with other data we may have revealed in the past. While separately they may be innocuous, there is a risk of future aggregation to create new information which one may find overly intrusive and not consent to. However, current data protection regimes make it hard for one to provide such consent, because there is no way for the user to know how his past and present data may be aggregated in the future.

- Data we consent to be collected for one specific purpose may be used in a myriad of other ways. The user has virtually no way to know how their data might be repurposed because often time neither do the collectors of that data[58].

Therefore, regulators reliance on principles of purpose limitation and the mechanism of consent for robust data protection seems suboptimal at the very least, as big data practices of aggregation, repurposing and secondary uses become commonplace.

Other problems with the mechanism of consent in the context of Big Data

On one end of the spectrum are situations where organisations garner consent for future secondary uses at the time of data collection. As discussed earlier, this is currently the common practice for organisations and the likelihood of users providing informed consent is low.

However, equally valid is considering the situations on the other end of the spectrum, where obtaining user consent for secondary use becomes too expensive and cumbersome[59]. As a result, potentially socially valuable secondary use of data for research and innovation or simply “the practice of informed and reflective citizenship”[60] may not take place. While potential social research may be hindered by the consent requirement, the reality that one cannot give meaningful consent to an unknown secondary uses of data is more pressing. Essentially, not knowing what you are consenting to scarcely provides the individual with any semblance of strong privacy protections and so the consent that individuals provide is superficial at best.

Many scholars also point to the binary nature of consent as it stands today[61]. Solove describes consent in data protection as nuanced[62] while Cate and Mayer-Schönberger go further to assert that “binary choice is not what the privacy architects envisioned four decades ago when they imagined empowered individuals making informed decisions about the processing of their personal data”. This dichotomous nature of consent further reduces its usefulness in data protection regimes.

Whether data collection is opted into or opted out of also has a bearing on the nature of the consent obtained. Many argue that regulations with options to opt out are not effective as “opt-out consent might be the product of mere inertia or lack of awareness of the option to opt out”[63]. This is in line with initiatives around the world to make gathering consent more explicit by having options to opt in instead of opt out. Noted articulations of the impetus to embrace opt in regimes include ex FTC chairman Jon Leibowitz as early as 2007[64], as well as being actively considered by the EU in the reform of their data protection laws[65].

However, as Solove rightly points out, opt in consent is problematic as well[66]. There are a few reasons for this: first, that many data collectors have the “sophistication and motivation to find ways to generate high opt-in rates”[67] by “conditioning products, services, or access on opting in”[68]. In essence, they leave individuals no choice but to opt into data collection because using their particular product or service is dependant or ‘conditional’ on explicit consent. A pertinent example of this is the end-user license agreement to Apple’s iTunes Store[69]. Solove rightly notes that “if people want to download apps from the store, they have no choice but to agree. This requirement is akin to an opt-in system — affirmative consent is being sought. But hardly any bargaining or choosing occurs in this process”[70]. Second, as stated earlier, obtaining consent runs the risk of impeding potential innovation or research because it is too cumbersome or expensive to obtain[71].

Third, as Tene and Polonetsky argue, “collective action problems threaten to generate a suboptimal equilibrium where individuals fail to opt into societally beneficial data processing in the hope of free-riding on others’ good will”[72]. A useful example to illustrate this comes from another context where obtaining consent is the difference between life and death: organ donation. The gulf in consenting donors between countries with an opt in regime for organ donation and countries with an opt out regime is staggering. Even countries that are culturally similar, such as Austria and Germany, exhibit vast differences in donation rates – Austria at 99% compared to just 12% in Germany[73]. This suggests that in terms of obtaining consent (especially for socially valuable actions), opt in methods may be limiting, because people may have an aversion to anything being presumed about their choices, even if costs of opting out are low[74].

What the above section demonstrates is how consent may be somewhat limited as a tool for data protection regimes, especially in a big data context. That said, consent is not in itself a useless or outdated concept. The problems raised above articulate the problems that relying on consent extensively pose in a big data context. Consent should still remain a part of data protection regimes. However, there are both better ways to obtain consent (for organisations that collect data) as well as other areas to focus regulatory attention on aside from the time of data collection.

What can organisations do better to obtain more meaningful consent

Organisations that collect data could alter the way the obtain user consent. Most people can attest to having checked a box that was lying surreptitiously next to the words ‘I agree’, thereby agreeing to the Terms and Conditions or End-user License Agreement for a particular service or product. This is in line with the need for both parties to assent to the terms of a contract as part of making valid a contract[75]. Some of the more common types of online agreements that users enter into are Clickwrap and Browsewrap agreements. A Clickwrap agreement is “formed entirely in an online environment such as the Internet, which sets forth the rights and obligations between parties”[76]. They “require a user to click "I agree" or “I accept” before the software can be downloaded or installed”[77]. On the other hand, Browsewrap agreements “try to characterize your simple use of their website as your ‘agreement’ to a set of terms and conditions buried somewhere on the site”[78].

Because Browsewrap agreements do not “require a user to engage in any affirmative conduct”[79], the kind of consent that these types of agreements obtain is highly superficial. In fact, many argue that such agreements are slightly unscrupulous because users are seldom aware that such agreements exist[80], often hidden in small print[81] or below the download button[82] for example. And the courts have begun to consider such terms and practices unfair, which “hold website users accountable for terms and conditions of which a reasonable Internet user would not be aware just by using the site”[83]. For example, In re Zappos.com Inc., Customer Data Security Breach Litigation, the court said of their Terms of Use (which is in a browsewrap agreement):

“The Terms of Use is inconspicuous, buried in the middle to bottom of every Zappos.com webpage among many other links, and the website never directs a user to the Terms of Use. No reasonable user would have reason to click on the Terms of Use”[84]

Clearly, courts recognise the potential for consent or assent to be obtained in a hardly transparent or hands on manner. Organisations that collect data should be aware of this and consider other options for obtaining consent.

A few commentators have suggested that organisations switch to using Clickwrap or clickthrough agreements to obtain consent. Undergirding this argument is the fact that courts have on numerous occasions, upheld the validity of a Clickwrap agreement. Such cases include Groff v. America Online, Inc[85] and Hotmail Corporation v. Van Money Pie, Inc[86]. These cases built upon the precedent-setting case of Pro CD v. Zeidenberg, in which the court ruled that “Shrinkwrap licenses are enforceable unless their terms are objectionable on grounds applicable to contracts in general”[87]. Shrinkwrap licenses, which refer to end user license agreements printed on the shrinkwrap of a software product which a user will definitely notice and have the opportunity to read before opening and using the product, and the rules that govern them, have seen application to clickthrough agreements. As Bayley rightly noted, the validity of clickthrough agreements is dependent on “reasonable notice and opportunity to review—whether the placement of the terms and click-button afforded the user a reasonable opportunity to find and read the terms without much effort”[88].

From the perspective of companies and other organisations which attempt to garner consent from users to collect and process their data, utilizing Clickwrap agreements might be one useful solution to consider in obtaining more meaningful and informed consent. In fact Bayley contends that clear Clickwrap agreements are “the “best practice” mechanism for creating a contractual relationship between an online service and a user”[89]. He suggests the following mechanism for acquiring clear and informed consent via contractual agreement[90]:

- Conspicuously present the TOS to the user prior to any payment (or other commitment by the user) or installation of software (or other changes to a user’s machine or browser, like cookies, plug-ins, etc.)

- Allow the user to easily read and navigate all of the terms (i.e. be in a normal, readable typeface with no scroll box)

- Provide an opportunity to print, and/or save a copy of, the terms

- Offer the user the option to decline as prominently and by the same method as the option to agree

- Ensure the TOS is easy to locate online after the user agrees.

These principles make a lot of sense for organisations, as it requires relatively minor procedural changes instead of more transformational efforts to alter the way the validate their data processing processes entirely.

Herzfield adds two further suggestions to this list. First, organisations should not allow any use of their product or service until “express and active manifestation of assent”[91]. Also, they should institute processes where users re-iterate their consent and assent to the terms of use[92]. He goes further to propose a baseline that organisations should follow: “companies should always provide at least inquiry notice of all terms, and require counterparties to manifest assent, through action or inaction, in a manner that reasonable people would clearly understand to be assent”[93].

While obtaining informed and meaningful consent is neither fool proof nor a process which has widely accepted clear steps, what is clear is that current efforts by organisations may be insufficient. As Cate and Mayer-Schönberger note, “data processors can perhaps too easily point to the formality of notice and consent and thereby abrogate much of their responsibility”[94]. One thing they can do to both ensure more meaningful and informed consent (from the perspective of the users) and preventing potential legal action for unscrupulous or unfair terms is to change the way they obtain consent from opt out to opt in.

Conclusion – how should regulation change

In conclusion, the current emphasis and extensive use of consent in data protection seems to be limited in effectively protecting against illegitimate processing of data in a big data context. More people are starting to use online services extensively. This is coupled by the fact that organisations are realizing the value of collecting and analysing user data to carry out data-driven analytics for insights that can improve the efficacy of the product. Clearly, data protection has never been more crucial.

However not only does emphasising consent seem less relevant, because the consent organisations obtain is seldom informed, but it may even jeopardise the intentions of data protection. Commentators are quick to point out how nimble firms are at acquiring consent in newer ways that may comply with laws but still allow them to maintain their advantageous position of asymmetric power. Kuner, Cate, Millard and Svantesson, all eminent scholars in the field of Big data, asked the prescient question: “Is there a proper role for individual consent?”[95]They believe consent still has a role, but that finding this role in the Big data context is challenging[96]. However, there is surprising consensus on the approach that should be taken as data protection regimes shift away from consent.

In fact, the alternative is staring at us in the face: data protection regimes have to look elsewhere, to other points along the data analysis process for aspects to regulate and ensure legitimate and fair processing of data. One compelling idea which had broad-based support during the aforementioned Microsoft Privacy Summit was that “new approaches must shift responsibility away from data subjects toward data users and toward a focus on accountability for responsible data stewardship”[97], ie creating regulations to guide data processing instead of the data collection. De Zwart et al. suggest that regulation must instead “focus on the processes involved in establishing algorithms and the use of the resulting conclusions”[98].

This might involve regulations relating to requiring data collectors to publish the queries they run on the data. This would be a solution that balances maintaining the ‘trade secret’ of the firm, who has creatively designed an algorithm, with ensuring fairness and legitimacy in data processing. One manifestation of this approach is in conceptualising procedural data due process which “would regulate the fairness of Big Data’s analytical processes with regard to how they use personal data (or metadata derived from or associated with personal data) in any adjudicative process, including processes whereby Big Data is being used to determine attributes or categories for an individual”[99]. While there is debate regarding the usefulness of a data due process, the idea of data due process is just part of the consortium of ideas surrounding alternatives to consent in data protection. The main point is that “greater transparency should be required if there are fewer opportunities for consent or if personal data can be lawfully collected without consent”[100].

It is also worth considering exactly what a single use of group or individual’s data is, and what types of uses or processes require a “greater form of authorization”[101]. Certain data processes could require special affirmative consent to be procured, which is not applicable for other less intimate matters. Canada’s Office of the Privacy Commissioner released a privacy toolkit for organisations, in which they provide some exceptions to the consent principle, one of which is if data collection “is clearly in the individual’s interests and consent is not available in a timely way”[102]. Some therefore suggest that “if notice and consent are reserved for more appropriate uses, individuals might pay more attention when this mechanism is used”[103].

Another option for regulators is to consider the development and implementation of a sticky privacy policies regime. This refers to “machine-readable policies [that] can stick to data to define allowed usage and obligations as it travels across multiple parties, enabling users to improve control over their personal information”[104]. Sticky privacy policies seem to alleviate the risk of repurposed, unanticipated uses of data because users who consent to giving out their data will be consenting to how it is used thereafter. However, the counter to sticky policies is that it places even greater obligations on users to decide how they would like their data used, not just at one point but for the long term. To expect organisations to state their purposes for future use of individuals data or that individuals are to give informed consent to such uses seems farfetched from both perspectives.

Still another solution draws from the noted scholar Helen Nissenbaum’s work on privacy. She argues that “the benchmark of privacy is contextual integrity”[105]. ”Contextual integrity ties adequate protection for privacy to norms of specific contexts, demanding that information gathering and dissemination be appropriate to that context and obey the governing norms of distribution within it”[106]. According to this line of thinking, legislators should instead focus their attention on what constitutes appropriateness in certain contexts, although this could be a challenging task as contexts merge and understandings of appropriateness change according to the circumstances of a context. .

While there is little consensus regarding the numerous ways to focus regulatory attention on data processing and the uses of data collected, there is more support for a shift away from consent, as exemplified by the Microsoft privacy Summit:

“There was broad general agreement that privacy frameworks that rely heavily on individual notice and consent are neither sustainable in the face of dramatic increases in the volume and velocity of information flows nor desirable because of the burden they place on individuals to understand the issues, make choices, and then engage in oversight and enforcement.”[107] I think Cate and Mayer- Schönberger make for the most valid conclusion to this article, as well as to summarise the debate I have presented. They say that “in short, ensuring individual control over personal data is not only an increasingly unattainable objective of data protection, but in many settings it is an undesirable one as well.”[108] We might very well be throwing the entire data protection regimes under the bus.

[1] Gordon Rayner and Bill Gardner, “Men Must Prove a Woman Said ‘Yes’ under Tough New Rape Rules - Telegraph,” The Telegraph, January 28, 2015, sec. Law and Order, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/law-and-order/11375667/Men-must-prove-a-woman-said-Yes-under-tough-new-rape-rules.html.

[2] Legal Information Institute, “Implied Consent,” accessed August 25, 2015, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/implied_consent.

[3] European Parliament, Council of the European Union, Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the Protection of Individuals with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, 1995, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX:31995L0046.

[4] See supra note 3.

[5] European Commission, “Stronger Data Protection Rules for Europe,” European Commission Press Release Database, June 15, 2015, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-15-5170_en.htm.

[6] Council of the European Union, “Data Protection: Council Agrees on a General Approach,” June 15, 2015, http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/06/15-jha-data-protection/.

[7] See supra note 6.

[8] Abraham L. Newman, Protectors of Privacy: Regulating Personal Data in the Global Economy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008).

[9] See supra note 8, at 24.

[10] Ibid.

[11] 15 U.S.C. §1681.

[12] 5 U.S.C. § 552a.

[13] 18 U.S.C. § 2510-22.

[14] Federal Trade Commission, “Privacy Online: A Report to Congress,” June 1998, https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/privacy-online-report-congress/priv-23a.pdf: 40.

[15] See supra note 14, at 8.

[16] Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, “2013 OECD Privacy Guidelines,” 2013, http://www.oecd.org/internet/ieconomy/privacy-guidelines.htm.

[17] Canadian Standards Association, “Canadian Standards Association Model Code,” March 1996, https://www.cippguide.org/2010/06/29/csa-model-code/.

[18] Mary Chlopecki, “The Property Rights Origins of Privacy Rights | Foundation for Economic Education,” August 1, 1992, http://fee.org/freeman/the-property-rights-origins-of-privacy-rights.

[19] See Pope v. Curl (1741), available here.

[20] See Prince Albert v. Strange (1849), available here.

[21] Samuel D. Warren and Louis D. Brandeis, “The Right to Privacy,” Harvard Law Review 4, no. 5 (December 15, 1890): 193–220, doi:10.2307/1321160.

[22] See supra note 18.

[23] Ibid.

[24] See supra note 21.

[25] See for example, Richard Epstein, “Privacy, Property Rights, and Misrepresentations,” Georgia Law Review, January 1, 1978, 455. And Richard Posner, “The Right of Privacy,” Sibley Lecture Series, April 1, 1978, http://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/lectures_pre_arch_lectures_sibley/22.

[26] See supra note 21, at 215.

[27] See supra note 21, at 218.

[29] Adrienne W. Fawcett, “Q: Who Said: ‘A Man’s Home Is His Castle’?,” Chicago Tribune, September 14, 1997, http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1997-09-14/news/9709140446_1_castle-home-sir-edward-coke.

[30] Brendan Purves, “Castle Doctrine from State to State,” South Source, July 15, 2011, http://source.southuniversity.edu/castle-doctrine-from-state-to-state-46514.aspx.

[31] “Volenti Non Fit Injuria,” E-Lawresources, accessed August 25, 2015, http://e-lawresources.co.uk/Volenti-non-fit-injuria.php.

[32] Bryce Clayton Newell, “Local Law Enforcement Jumps on the Big Data Bandwagon: Automated License Plate Recognition Systems, Information Privacy, and Access to Government Information,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, October 16, 2013), http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2341182.

[33] Alan Westin, Privacy and Freedom (Ig Publishing, 2015).

[34] Helen Nissenbaum, “Privacy as Contextual Integrity,” Washington Law Review 79 (2004): 119.

[35] Ruth Gavison, “Privacy and the Limits of Law,” The Yale Law Journal 89, no. 3 (January 1, 1980): 421–71, doi:10.2307/795891: 423.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Daniel J. Solove, “Privacy Self-Management and the Consent Dilemma,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, November 4, 2012), http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2171018: 1888.

[38] Ibid, at 1889.

[39] Omer Tene and Jules Polonetsky, “Big Data for All: Privacy and User Control in the Age of Analytics,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, September 20, 2012), http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2149364: 261.

[40] See supra note 37, at 1881.

[41] Fred H. Cate and Viktor Mayer-Schönberger, “Notice and Consent in a World of Big Data - Microsoft Global Privacy Summit Summary Report and Outcomes,” Microsoft Global Privacy Summit, November 9, 2012, http://www.microsoft.com/en-us/download/details.aspx?id=35596: 3.

[42] See supra note 39.

[43] See for example, US Securities and Exchange Commission, “Corporation Finance Small Business Compliance Guides,” accessed August 26, 2015, https://www.sec.gov/info/smallbus/secg.shtml and Australian Securities & Investments Commission, “Compliance for Small Business,” accessed August 26, 2015, http://asic.gov.au/for-business/your-business/small-business/compliance-for-small-business/.

[44] See supra note 39.

[45] See supra note 41.

[46] See supra note 8, at 24.

[47] See for example, James Daley, “Don’t Waste Time Reading Terms and Conditions,” The Telegraph, September 3, 2014, and Robert Glancy, “Will You Read This Article about Terms and Conditions? You Really Should Do,” The Guardian, April 24, 2014, sec. Comment is free, http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/apr/24/terms-and-conditions-online-small-print-information.

[48] See supra note 37, at 1886.

[49] Alex Hudson, “Is Small Print in Online Contracts Enforceable?,” BBC News, accessed August 26, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-22772321.

[50] Aleecia M. McDonald and Lorrie Faith Cranor, “Cost of Reading Privacy Policies, The,” I/S: A Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society 4 (2009 2008): 541

[51] See supra note 41, at 4.

[52] For Canada, see Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, “Fact Sheet: Ten Tips for a Better Online Privacy Policy and Improved Privacy Practice Transparency,” October 23, 2013, https://www.priv.gc.ca/resource/fs-fi/02_05_d_56_tips2_e.asp. And Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, “Privacy Toolkit - A Guide for Businesses and Organisations to Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act,” accessed August 26, 2015, https://www.priv.gc.ca/information/pub/guide_org_e.pdf.

For USA, see Federal Trade Commission, “Internet of Things: Privacy & Security in a Connected World,” Staff Report (Federal Trade Commission, January 2015), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-staff-report-november-2013-workshop-entitled-internet-things-privacy/150127iotrpt.pdf.

[53] See supra note 37, at 1889.

[54] See supra note 39, at 261.

[55] Jakki Geiger, “The Surprising Link Between Hurricanes and Strawberry Pop-Tarts: Brought to You by Clean, Consistent and Connected Data,” The Informatica Blog - Perspectives for the Data Ready Enterprise, October 3, 2014, http://blogs.informatica.com/2014/03/10/the-surprising-link-between-strawberry-pop-tarts-and-hurricanes-brought-to-you-by-clean-consistent-and-connected-data/#fbid=PElJO4Z_kOu.

[56] Constance L. Hays, “What Wal-Mart Knows About Customers’ Habits,” The New York Times, November 14, 2004, http://www.nytimes.com/2004/11/14/business/yourmoney/what-walmart-knows-about-customers-habits.html.

[57] M. J. de Zwart, S. Humphreys, and B. Van Dissel, “Surveillance, Big Data and Democracy: Lessons for Australia from the US and UK,” Http://www.unswlawjournal.unsw.edu.au/issue/volume-37-No-2, 2014, https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/handle/2440/90048: 722.

[58] Ibid.

[59] See supra note 41, at 3.

[60] Julie E. Cohen, “What Privacy Is For,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, November 5, 2012), http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2175406.

[61] See supra note 37, at 1901.

[62] Ibid.

[63] See supra note 37, at 1899.