This policy brief analyses the different laws regulating surveillance at the State and Central level in India and calls out ways in which the provisions are unharmonized. The brief then provides recommendations for the harmonization of surveillance law in India.

Introduction

The current legal framework for surveillance in India is a legacy of the colonial era laws that had been drafted by the British. Surveillance activities by the police are an everyday phenomenon and are included as part of their duties in the various police manuals of the different states. It will become clear from an analysis of the laws and regulations below, that whilst the police manuals cover the aspect of physical surveillance in some detail, they do not discuss the issue of interception of telephone or internet traffic. These issues are dealt with separately under the Telecom Act and the Information Technology Act and the Rules made thereunder, which are applicable to all security agencies and not just the police. Since the Indian laws deal with different aspects of surveillance under different legislations, the regulations dealing with this issue do not have any uniform standards. This paper therefore argues that the need of the hour is to have a single legislation which deals with all aspects of surveillance and interception in one place so that there is uniformity in the laws and practices of surveillance in the entire country.

Legal Regime

India does not have one integrated policy on surveillance and law enforcement and security agencies have to rely upon a number of different sectoral legislations to carry out their surveillance activities. These include:

1. Police Surveillance under Police Acts and Model Police Manual

Article 246(3) of the Constitution of India, read with Entry 2, List II, of the VIIth Schedule, empowers the States to legislate in matters relating to the police. This means that the police force is under the control of the state government rather than the Central government. Consequently, States have their own Police Acts to govern the conduct of the police force. Under the authority of these individual State Police Acts, rules are formulated for day-to-day running of the police. These rules are generally found in the Police Manuals of the individual states. Since a discussion of the Police Manual of each State with its small deviations is beyond the scope of this study, we will discuss the Model Police Manual issued by the Bureau of Police Research and Development.

As per the Model Police Manual, “surveillance and checking of bad characters” is considered to be one of the duties of the police force mentioned in the “Inventory of Police Duties, Functions and Jobs”.[1] Surveillance is also one of the main methods utilized by the police for preventing law and order situations and crimes.[2] As per the Manual the nature and degree of surveillance depends on the circumstances and persons on whom surveillance is mounted and it is only in very rare cases and on rare occasions that round the clock surveillance becomes necessary for a few days or weeks.[3]

Surveillance of History Sheeted Persons: Beat Police Officers should be fully conversant with the movements or changes of residence of all persons for whom history sheets of any category are maintained. They are required to promptly report the exact information to the Station House Officer (SHO), who make entries in the relevant registers. The SHO on the basis of this information reports, by the quickest means, to the SHO in whose jurisdiction the concerned person/persons are going to reside or pass through. When a history-sheeted person is likely to travel by the Railway, intimation of his movements should also be given to the nearest Railway Police Station.[4] It must be noted that the term “history sheet” or “history sheeter” is not defined either in the Indian Penal Code, 1860, most of the State Police Acts or the Model Police Manual, but it is generally understood and defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as persons with a criminal record.

Surveillance of “Bad Characters”: Keeping tabs on and getting information regarding “bad characters” is part of the duties of a beat constable. In the case of a “bad character” who is known to have gone to another State, the SHO of the station in the other state is informed using the quickest means possible followed by sending of a BC Roll 'A' directly to the SHO.[5] When a “bad character” absents himself or goes out of view, whether wanted in a case or not, the information is required to be disseminated to the police stations having jurisdiction over the places likely to be visited by him and also to the neighbouring stations, whether within the State or outside. If such person is traced and intimation is received of his arrest or otherwise, arrangements to get a complete and true picture of his activities are required to be made and the concerned record updated.[6]

The Police Manual clarifies the term “bad characters” to mean “offenders, criminals, or members of organised crime gangs or syndicates or those who foment or incite caste, communal violence, for which history sheets are maintained and require surveillance.”[7] A fascinating glimpse into the history of persons who were considered to be “bad characters” is contained in the article by Surjan Das & Basudeb Chattopadhyay in EPW[8] wherein they bring out the fact that in colonial times a number of the stereotypes propagated by the British crept into their police work as well. It appears that one did not have to be convicted to be a bad character, but people with a dark complexion, strong built, broad chins, deep-set eyes, broad forehead, short hair, scanty or goatee beard, marks on face, moustache, blunt nose, white teeth and monkey-face would normally fit the description of “bad characters”.

Surveillance of Suspicious Strangers: When a stranger of suspicious conduct or demeanour is found within the limits of a police station, the SHO is required to forward a BC Roll to the Police Station in whose jurisdiction the stranger claims to have resided. The receipt of such a roll is required to be immediately acknowledged and replied. If the suspicious stranger states that he resides in another State, a BC Roll is sent directly to the SHO of the station in the other State.[9] The manual however, does not define who a “suspicious stranger” is and how to identify one.

Release of Foreign Prisoners: Before a foreign prisoner (whose finger prints are taken for record) is released the Superintendent of Police of the district where the case was registered is required to send a report to the Director, I.B. through the Criminal Investigation Department informing the route and conveyance by which such person is likely to leave the country.[10]

Shadowing of convicts and dangerous persons: The Police Manual contains the following rules for shadowing the convicts on their release from jails:

(a) Dangerous convicts who are not likely to return to their native places are required to be shadowed. The fact, when a convict is to be shadowed is entered in the DCRB in the FP register and communicated to the Superintendent of Jails.

(b) The Police Officer deputed for shadowing an ex-convict is required to enter the fact in the notebook. The Police Officers area furnished with a challan indicating the particulars of the ex-convict marked for shadowing. This form is returned by the SHO of the area where the ex-convict takes up his residence or passes out of view to the DCRB / OCRS where the jail is situated, where it is put on record for further reference and action if any. Even though the subjects being shadowed are kept in view, no restraint is to put upon their movements on any account.[11]

Apart from the provisions discussed above, there are also provisions in the Police Manual regarding surveillance of convicts who have been released on medical grounds as well as surveillance of ex-convicts who are required to report their movements to the police as per the provisions of section 356 of the Code of Criminal Procedure.[12]

As noted above, the various police manuals are issued under the State Police Acts and they govern the police force of the specific states. The fact that each state has its own individual police manual itself leads to non-uniformity regarding standards and practices of surveillance. But it is not only the legislations at the State levels which lead to this problem, even legislation at the Central level, which are applicable to the country as a whole also have differing standards regarding different aspects of surveillance. In order to explore this further, we shall now discuss the central legislations dealing with surveillance.

2. The Indian Telegraph Act, 1885

Section 5 of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885, empowers the Central Government and State Governments of India to order the interception of messages in two circumstances: (1) in the occurrence of any public emergency or in the interest of public safety, and (2) if it is considered necessary or expedient to do so in the interest of:[13]

- the sovereignty and integrity of India; or

- the security of the State; or

- friendly relations with foreign states; or

- public order; or

- for preventing incitement to the commission of an offence.

The Supreme Court of India has specified the terms 'public emergency' and 'public safety', based on the following[14]:

"Public emergency would mean the prevailing of a sudden condition or state of affairs affecting the people at large calling for immediate action. The expression 'public safety' means the state or condition of freedom from danger or risk for the people at large. When either of these two conditions are not in existence, the Central Government or a State Government or the authorised officer cannot resort to telephone tapping even though there is satisfaction that it is necessary or expedient so to do in the interests of it sovereignty and integrity of India etc. In other words, even if the Central Government is satisfied that it is necessary or expedient so to do in the interest of the sovereignty and integrity of India or the security of the State or friendly relations with sovereign States or in public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of an offence, it cannot intercept the message, or resort to telephone tapping unless a public emergency has occurred or the interest of public safety or the existence of the interest of public safety requires. Neither the occurrence of public emergency nor the interest of public safety are secretive conditions or situations. Either of the situations would be apparent to a reasonable person."

In 2007, Rule 419A was added to the Indian Telegraph Rules, 1951 framed under the Indian Telegraph Act which provided that orders on the interception of communications should only be issued by the Secretary in the Ministry of Home Affairs. However, it provided that in unavoidable circumstances an order could also be issued by an officer, not below the rank of a Joint Secretary to the Government of India, who has been authorised by the Union Home Secretary or the State Home Secretary.[15]

According to Rule 419A, the interception of any message or class of messages is to be carried out with the prior approval of the Head or the second senior most officer of the authorised security agency at the Central Level and at the State Level with the approval of officers authorised in this behalf not below the rank of Inspector General of Police, in the belowmentioned emergent cases:

- in remote areas, where obtaining of prior directions for interception of messages or class of messages is not feasible; or

- for operational reasons, where obtaining of prior directions for interception of message or class of messages is not feasible;

however, the concerned competent authority is required to be informed of such interceptions by the approving authority within three working days and such interceptions are to be confirmed by the competent authority within a period of seven working days. If the confirmation from the competent authority is not received within the stipulated seven days, such interception should cease and the same message or class of messages should not be intercepted thereafter without the prior approval of the Union Home Secretary or the State Home Secretary.[16]

Rule 419A also tries to incorporate certain safeguards to curb the risk of unrestricted surveillance by the law enforcement authorities which include the following:

- Any order for interception issued by the competent authority should contain reasons for such direction and a copy of such an order should be forwarded to the Review Committee within a period of seven working days;[17]

- Directions for interception should be issued only when it is not possible to acquire the information by any other reasonable means;[18]

- The directed interception should include the interception of any message or class of messages that are sent to or from any person n or class of persons or relating to any particular subject whether such message or class of messages are received with one or more addresses, specified in the order being an address or addresses likely to be used for the transmission of communications from or to one particular person specified or described in the order or one particular set of premises specified or described in the order;[19]

- The interception directions should specify the name and designation of the officer or the authority to whom the intercepted message or class of messages is to be disclosed to;[20]

- The directions for interception would remain in force for sixty days, unless revoked earlier, and may be renewed but the same should not remain in force beyond a total period of one hundred and eighty days;[21]

- The directions for interception should be conveyed to the designated officers of the licensee(s) in writing by an officer not below the rank of Superintendent of Police or Additional Superintendent of Police or the officer of the equivalent rank;[22]

- The officer authorized to intercept any message or class of messages should maintain proper records mentioning therein, the intercepted message or class of messages, the particulars of persons whose message has been intercepted, the name and other particulars of the officer or the authority to whom the intercepted message or class of messages has been disclosed, etc.;[23]

- All the requisitioning security agencies should designate one or more nodal officers not below the rank of Superintendent of Police or the officer of the equivalent rank to authenticate and send the requisitions for interception to the designated officers of the concerned service providers to be delivered by an officer not below the rank of Sub-Inspector of Police;[24]

- Records pertaining to directions for interception and of intercepted messages should be destroyed by the competent authority and the authorized security and Law Enforcement Agencies every six months unless these are, or likely to be, required for functional requirements;[25]

According to Rule 419A, service providers \are required by law enforcement to intercept communications are required to comply with the following[26]:

- Service providers should designate two senior executives of the company in every licensed service area/State/Union Territory as the nodal officers to receive and handle such requisitions for interception;[27]

- The designated nodal officers of the service providers should issue acknowledgment letters to the concerned security and Law Enforcement Agency within two hours on receipt of intimations for interception;[28]

- The system of designated nodal officers for communicating and receiving the requisitions for interceptions should also be followed in emergent cases/unavoidable cases where prior approval of the competent authority has not been obtained;[29]

- The designated nodal officers of the service providers should forward every fifteen days a list of interception authorizations received by them during the preceding fortnight to the nodal officers of the security and Law Enforcement Agencies for confirmation of the authenticity of such authorizations;[30]

- Service providers are required to put in place adequate and effective internal checks to ensure that unauthorized interception of messages does not take place, that extreme secrecy is maintained and that utmost care and precaution is taken with regards to the interception of messages;[31]

- Service providers are held responsible for the actions of their employees. In the case of an established violation of license conditions pertaining to the maintenance of secrecy and confidentiality of information and unauthorized interception of communication, action shall be taken against service providers as per the provisions of the Indian Telegraph Act, and this shall not only include a fine, but also suspension or revocation of their license;[32]

- Service providers should destroy records pertaining to directions for the interception of messages within two months of discontinuance of the interception of such messages and in doing so they should maintain extreme secrecy.[33]

Review Committee

Rule 419A of the Indian Telegraph Rules requires the establishment of a Review Committee by the Central Government and the State Government, as the case may be, for the interception of communications, as per the following conditions:[34]

(1) The Review Committee to be constituted by the Central Government shall consist of the following members, namely:

(a) Cabinet Secretary - Chairman

(b) Secretary to the Government of India in charge, Legal Affairs - Member

(c) Secretary to the Government of India, Department of Telecommunications – Member

(2) The Review Committee to be constituted by a State Government shall consist of the following members, namely:

(a) Chief Secretary – Chairman

(b) Secretary Law/Legal Remembrancer in charge, Legal Affairs – Member

(c) Secretary to the State Government (other than the Home Secretary) – Member

(3) The Review Committee meets at least once in two months and records its findings on whether the issued interception directions are in accordance with the provisions of sub-section (2) of Section 5 of the Indian Telegraph Act. When the Review Committee is of the opinion that the directions are not in accordance with the provisions referred to above it may set aside the directions and order for destruction of the copies of the intercepted message or class of messages;[35]

It must be noted that the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, (which is currently used against most acts of urban terrorism) also allows for the interception of communications but the procedures and safeguards are supposed to be the same as under the Indian Telegraph Act and the Information Technology Act.[36]

3. Telecom Licenses

The telecom sector in India has seen immense activity in the last two decades ever since it was opened up to private competition. These last twenty years have seen a lot of turmoil and have offered a tremendous learning opportunity for the private players as well as the governmental bodies regulating the sector. Currently any entity wishing to get a telecom license is offered a UL (Unified License) which contains terms and conditions for all the services that a licensee may choose to offer. However there were a large number of other licenses before the current regime, and since the licenses have a long phase out, we have tried to cover what we believe are the four most important licenses issued to telecom operators starting with the CMTS License:

Cellular Mobile Telephony Services (CMTS) License

In terms of National Telecom Policy (NTP)-1994, the first phase of liberalization in mobile telephone service started with issue of 8 licenses for Cellular Mobile Telephony Services (CMTS) in the 4 metro cities of Delhi, Mumbai, Calcutta and Chennai to 8 private companies in November 1994. Subsequently, 34 licenses for 18 Territorial Telecom Circles were also issued to 14 private companies during 1995 to 1998. During this period a maximum of two licenses were granted for CMTS in each service area and these licensees were called 1st & 2nd cellular licensees.[37] Consequent upon announcement of guidelines for Unified Access (Basic & Cellular) Services licenses on 11.11.2003, some of the CMTS operators were permitted to migrate from CMTS License to Unified Access Service License (UASL) but currently no new CMTS and Basic service licenses are being awarded after issuing the guidelines for Unified Access Service Licence (UASL).

The important provisions regarding surveillance in the CMTS License are listed below:

Facilities for Interception: The CMTS License requires the Licensee to provide necessary facilities to the designated authorities for interception of the messages passing through its network.[38]

Monitoring of Telecom Traffic: The designated person of the Central/State Government as conveyed to the Licensor from time to time in addition to the Licensor or its nominee have the right to monitor the telecommunication traffic in every MSC or any other technically feasible point in the network set up by the licensee. The Licensee is required to make arrangement for monitoring simultaneous calls by Government security agencies. The hardware at licensee’s end and software required for monitoring of calls shall be engineered, provided/installed and maintained by the Licensee at licensee’s cost. In case the security agencies intend to locate the equipment at licensee’s premises for facilitating monitoring, the licensee is required to extend all support in this regard including space and entry of the authorised security personnel. The interface requirements as well as features and facilities as defined by the Licensor are to be implemented by the licensee for both data and speech. The Licensee is also required to ensure suitable redundancy in the complete chain of Monitoring equipment for trouble free operations of monitoring of at least 210 simultaneous calls.[39]

Monitoring Records to be maintained: Along with the monitored call following records are to be made available:

- Called/calling party mobile/PSTN numbers.

- Time/date and duration of interception.

- Location of target subscribers. Cell ID should be provided for location of the target subscriber. However, Licensor may issue directions from time to time on the precision of location, based on technological developments and integration of Global Positioning System (GPS) which shall be binding on the LICENSEE.

- Telephone numbers if any call-forwarding feature has been invoked by target subscriber.

- Data records for even failed call attempts.

- CDR (Call Data Record) of Roaming Subscriber.

The Licensee is required to provide the call data records of all the specified calls handled by the system at specified periodicity, as and when required by the security agencies.[40]

Protection of Privacy: It is the responsibility of the Licensee to ensure the protection of privacy of communication and ensure unathorised interception of messages does not take place.[41]

License Agreement for Provision of Internet Services (ISP License)

Internet services were launched in India on 15th August, 1995 by Videsh Sanchar Nigam Limited. In November, 1998, the Government opened up the sector for providing Internet services by private operators. The major provisions dealing with surveillance contained in the ISP License are given below:

Authorization for monitoring: Monitoring shall only be by the authorization of the Union Home Secretary or Home Secretaries of the States/Union Territories.[42]

Access to subscriber list by authorized intelligence agencies and licensor: The complete and up to date list of subscribers will be made available by the ISP on a password protected website – accessible to authorized intelligence agencies.[43] Information such as customer name, IP address, bandwidth provided, address of installation, data of installation, contact number and email of leased line customers shall be included in the website.[44] The licensor or its representatives will also have access to the Database relating to the subscribers of the ISP which is to be available at any instant.[45]

Right to monitor by the central/state government: The designated person of the central/state government or the licensor or nominee will have the right to monitor telecommunications traffic in every node or any other technically feasible point in the network. To facilitate this, the ISP must make arrangements for the monitoring of simultaneous calls by the Government or its security agencies.[46]

Right of DoT to monitor: DoT will have the ability to monitor customers who generate high traffic value and verify specified user identities on a monthly basis.[47]

Provision of mirror images: Mirror images of the remote access information should be made available online for monitoring purposes.[48] A safeguard provided for in the license is that remote access to networks is only allowed in areas approved by the DOT in consultation with the Security Agencies.[49]

Provision of information stored on dedicated transmission link: The ISP will provide the login password to DOT and authorized Government agencies on a monthly basis for access to information stored on any dedicated transmission link from ISP node to subscriber premises.[50]

Provision of subscriber identity and geographic location: The ISP must provide the traceable identity and geographic location of their subscribers, and if the subscriber is roaming – the ISP should try to find traceable identities of roaming subscribers from foreign companies.[51]

Facilities for monitoring: The ISP must provide the necessary facilities for continuous monitoring of the system as required by the licensor or its authorized representatives.[52]

Facilities for tracing: The ISP will also provide facilities for the tracing of nuisance, obnoxious or malicious calls, messages, or communications. These facilities are to be provided specifically to authorized officers of the Government of India (police, customs, excise, intelligence department) when the information is required for investigations or detection of crimes and in the interest of national security.[53]

Facilities and equipment to be specified by government: The types of interception equipment to be used will be specified by the government of India.[54] This includes the installation of necessary infrastructure in the service area with respect to Internet Telephony Services offered by the ISP including the processing, routing, directing, managing, authenticating the internet calls including the generation of Call Details Record, IP address, called numbers, date, duration, time, and charge of the internet telephony calls.[55]

Facilities for surveillance of mobile terminal activity: The ISP must also provide the government facilities to carry out surveillance of Mobile Terminal activity within a specified area whenever requested.[56]

Facilities for monitoring international gateway: As per the requirements of security agencies, every international gateway location having a capacity of 2 Mbps or more will be equipped will have a monitoring center capable of monitoring internet telephony traffic.[57]

Facilities for monitoring in the premise of the ISP: Every office must be at least 10x10 with adequate power, air conditioning, and accessible only to the monitoring agencies. One local exclusive telephone line must be provided, and a central monitoring center must be provided if the ISP has multiple nodal points.[58]

Protection of privacy: There is a responsibility on the ISP to protect the privacy of its communications transferred over its network. This includes securing the information and protecting against unauthorized interception, unauthorized disclosure, ensure the confidentiality of information, and protect against over disclosure of information- except when consent has been given.[59]

Log of users: Each ISP must maintain an up to date log of all users connected and the service that they are using (mail, telnet, http, etc). The ISPs must also log every outward login or telnet through their computers. These logs as well as copies of all the packets must be made available in real time to the Telecom Authority.[60]

Log of internet leased line customers: A record of each internet leased line customer should be kept along with details of connectivity, and reasons for taking the link should be kept and made readily available for inspection.[61]

Log of remote access activities: The ISP will also maintain a complete audit trail of the remote access activities that pertain to the network for at least six months. This information must be available on request for any agency authorized by the licensor.[62]

Monitoring requirements: The ISP must make arrangements for the monitoring of the telecommunication traffic in every MSC exchange or any other technically feasible point, of at least 210 calls simultaneously.[63]

Records to be made available:

- CDRS: When required by security agencies, the ISP must make available records of i) called/calling party mobile/PSTN numbers ii) time/date and duration of calls iii) location of target subscribers and from time to time precise location iv) telephone numbers – and if any call forwarding feature has been evoked – records thereof v) data records for failed call attempts vi) CDR of roaming subscriber.[64]

- Bulk connections: On a monthly basis, and from time to time, information with respect to bulk connections shall be forwarded to DoT, the licensor, and security agencies.[65]

- Record of calls beyond specified threshold: Calls should be checked, analyzed, and a record maintained of all outgoing calls made by customers both during the day and night that exceed a set threshold of minutes. A list of suspected subscribers should be created by the ISP and should be informed to DoT and any officer authorized by the licensor at any point of time.[66]

- Record of subscribers with calling line identification restrictions: Furthermore, a list of calling line identification restriction subscribers with their complete address and details should be created on a password protected website that is available to authorized government agencies.[67]

Unified Access Services (UAS) License

Unified Access Services operators provide services of collection, carriage, transmission and delivery of voice and/or non-voice messages within their area of operation, over the Licensee’s network by deploying circuit and/or packet switched equipment. They may also provide Voice Mail, Audiotex services, Video Conferencing, Videotex, E-Mail, Closed User Group (CUG) as Value Added Services over its network to the subscribers falling within its service area on a non-discriminatory basis.

The terms of providing the services are regulated under the Unified Access Service License (UASL) which also contains provisions regarding surveillance/interception. These provisions are regularly used by the state agencies to intercept telephonic and data traffic of subscribers. The relevant terms of the UASL dealing with surveillance and interception are discussed below:

Confidentiality of Information: The Licensee cannot employ bulk encryption equipment in its network. Any encryption equipment connected to the Licensee’s network for specific requirements has to have prior evaluation and approval of the Licensor or officer specially designated for the purpose. However, any encryption equipment connected to the Licensee’s network for specific requirements has to have prior evaluation and approval of the Licensor or officer specially designated for the purpose. However, the Licensee has the responsibility to ensure protection of privacy of communication and to ensure that unauthorised interception of messages does not take place.[68] The Licensee shall take necessary steps to ensure that the Licensee and any person(s) acting on its behalf observe confidentiality of customer information.[69]

Responsibility of the Licensee: The Licensee has to take all necessary steps to safeguard the privacy and confidentiality of any information about a third party and its business to whom it provides the service and from whom it has acquired such information by virtue of the service provided and shall use its best endeavors to secure that :

- No person acting on behalf of the Licensee or the Licensee divulges or uses any such information except as may be necessary in the course of providing such service to the third party; and

- No such person seeks such information other than is necessary for the purpose of providing service to the third party.[70]

Provision of monitoring facilities: Requisite monitoring facilities /equipment for each type of system used, shall be provided by the service provider at its own cost for monitoring as and when required by the licensor.[71] The license also requires the Licensee to provide necessary facilities to the designated authorities for interception of the messages passing through its network.[72] The licensor in this case is the President of India, as the head of the State, therefore all references to the term licensor can be assumed to be to the government of India (which usually acts through the department of telecom (DOT). For monitoring traffic, the licensee company has to provide access of their network and other facilities as well as to books of accounts to the security agencies.[73]

Monitoring by Designated Person: The designated person of the Central/ State Government as conveyed to the Licensor from time to time in addition to the Licensor or its nominee has the right to monitor the telecommunication traffic in every MSC/Exchange/MGC/MG or any other technically feasible point in the network set up by the Licensee. The Licensee is required to make arrangement for monitoring simultaneous calls by Government security agencies. The hardware at Licensee’s end and software required for monitoring of calls shall be engineered, provided/installed and maintained by the Licensee at Licensee’s cost. However, the respective Government instrumentality bears the cost of user end hardware and leased line circuits from the MSC/ Exchange/MGC/MG to the monitoring centres to be located as per their choice in their premises or in the premises of the Licensee. In case the security agencies intend to locate the equipment at Licensee’s premises for facilitating monitoring, the Licensee should extend all support in this regard including space and entry of the authorized security personnel. The Licensee is required to implement the interface requirements as well as features and facilities as defined by the Licensor for both data and speech. The Licensee is to ensure suitable redundancy in the complete chain of Monitoring equipment for trouble free operations of monitoring of at least 210 simultaneous calls for seven security agencies.[74]

Monitoring Records to be maintained: Along with the monitored call following records are to be made available:

- Called/calling party mobile/PSTN numbers.

- Time/date and duration of interception.

- Location of target subscribers. Cell ID should be provided for location of the target subscriber. However, Licensor may issue directions from time to time on the precision of location, based on technological developments and integration of Global Positioning System (GPS) which shall be binding on the LICENSEE.

- Telephone numbers if any call-forwarding feature has been invoked by target subscriber.

- Data records for even failed call attempts.

- CDR (Call Data Record) of Roaming Subscriber.

The Licensee is required to provide the call data records of all the specified calls handled by the system at specified periodicity, as and when required by the security agencies.[75]

List of Subscribers: The complete list of subscribers shall be made available by the Licensee on their website (having password controlled access), so that authorized Intelligence Agencies are able to obtain the subscriber list at any time, as per their convenience with the help of the password.[76] The Licensor or its representative(s) have an access to the Database relating to the subscribers of the Licensee. The Licensee shall also update the list of his subscribers and make available the same to the Licensor at regular intervals. The Licensee shall make available, at any prescribed instant, to the Licensor or its authorized representative details of the subscribers using the service.[77] The Licensee must provide traceable identity of their subscribers,[78] and should be able to provide the geographical location (BTS location) of any subscriber at a given point of time, upon request by the Licensor or any other agency authorized by it.[79]

CDRs for Large Number of Outgoing Calls: The call detail records for outgoing calls made by subscribers making large number of outgoing calls day and night and to the various telephone numbers should be analyzed. Normally, no incoming call is observed in such cases. This can be done by running special programs for this purpose.[80] Although this provision itself does not say that it is limited to bulk subscribers (subscribers with more than 10 lines), it is contained as a sub-clause of section 41.19 which talks about specific measures for bulk subscribers, therefore it is possible that this provision is limited only to bulk subscribers and not to all subscribers.

No Remote Access to Suppliers: Suppliers/manufacturers and affiliate(s) are not allowed any remote access to the be enabled to access Lawful Interception System(LIS), Lawful Interception Monitoring(LIM), Call contents of the traffic and any such sensitive sector/data, which the licensor may notify from time to time, under any circumstances.[81] The Licensee is also not allowed to use remote access facility for monitoring of content.[82] Further, suitable technical device is required to be made available at Indian end to the designated security agency/licensor in which a mirror image of the remote access information is available on line for monitoring purposes.[83]

Monitoring as per the Rules under Telegraph Act: In order to maintain the privacy of voice and data, monitoring shall be in accordance with rules in this regard under Indian Telegraph Act, 1885.[84] It interesting to note that the monitoring under the UASL license is required to be as per the Rules prescribed under the Telegraph Act, but no mention is made of the Rules under the Information Technology Act.

Monitoring from Centralised Location: The Licensee has to ensure that necessary provision (hardware/ software) is available in its equipment for doing lawful interception and monitoring from a centralized location.[85]

Unified License (UL)

The National Telecom Policy - 2012 recognized the fact that the evolution from analog to digital technology has facilitated the conversion of voice, data and video to the digital form which are increasingly being rendered through single networks bringing about a convergence in networks, services and devices. It was therefore felt imperative to move towards convergence between various services, networks, platforms, technologies and overcome the incumbent segregation of licensing, registration and regulatory mechanisms in these areas. It was for this reason that the Government of India decided to move to the Unified License regime under which service providers could opt for all or any one or more of a number of different services.[86]

Provision of interception facilities by Licensee: The UL requires that the requisite monitoring/ interception facilities /equipment for each type of service, should be provided by the Licensee at its own cost for monitoring as per the requirement specified by the Licensor from time to time.[87] The Licensee is required to provide necessary facilities to the designated authorities of Central/State Government as conveyed by the Licensor from time to time for interception of the messages passing through its network, as per the provisions of the Indian Telegraph Act.[88]

Bulk encryption and unauthorized interception: The UL prohibits the Licensee from employing bulk encryption equipment in its network. Licensor or officers specially designated for the purpose are allowed to evaluate any encryption equipment connected to the Licensee’s network. However, it is the responsibility of the Licensee to ensure protection of privacy of communication and to ensure that unauthorized interception of messages does not take place.[89] The use of encryption by the subscriber shall be governed by the Government Policy/rules made under the Information Technology Act, 2000.[90]

Safeguarding of Privacy and Confidentiality: The Licensee shall take necessary steps to ensure that the Licensee and any person(s) acting on its behalf observe confidentiality of customer information.[91] Subject to terms and conditions of the license, the Licensee is required to take all necessary steps to safeguard the privacy and confidentiality of any information about a third party and its business to whom it provides services and from whom it has acquired such information by virtue of the service provided and shall use its best endeavors to secure that: a) No person acting on behalf of the Licensee or the Licensee divulges or uses any such information except as may be necessary in the course of providing such service; and b) No such person seeks such information other than is necessary for the purpose of providing service to the third party.

Provided the above para does not apply where: a) The information relates to a specific party and that party has consented in writing to such information being divulged or used, and such information is divulged or used in accordance with the terms of that consent; or b) The information is already open to the public and otherwise known.[92]

No Remote Access to Suppliers: Suppliers/manufacturers and affiliate(s) are not allowed any remote access to the be enabled to access Lawful Interception System(LIS), Lawful Interception Monitoring(LIM), Call contents of the traffic and any such sensitive sector/data, which the licensor may notify from time to time, under any circumstances.[93] The Licensee is also not allowed to use remote access facility for monitoring of content.[94] Further, suitable technical device is required to be made available at Indian end to the designated security agency/licensor in which a mirror image of the remote access information is available on line for monitoring purposes.[95]

Monitoring as per the Rules under Telegraph Act: In order to maintain the privacy of voice and data, monitoring shall be in accordance with rules in this regard under Indian Telegraph Act, 1885.[96] Just as in the UASL, the monitoring under the UL license is required to be as per the Rules prescribed under the Telegraph Act, but no mention is made of the Rules under the Information Technology Act.

Terms specific to various services

Since the UL License intends to cover all services under a single license, in addition to the general terms and conditions for interception, it also has terms for each specific service. We shall now discuss the terms for interception specific to each service offered under the Unified License.

Access Service: The designated person of the Central/ State Government, in addition to the Licensor or its nominee, shall have the right to monitor the telecommunication traffic in every MSC/ Exchange/ MGC/ MG/ Routers or any other technically feasible point in the network set up by the Licensee. The Licensee is required to make arrangement for monitoring simultaneous calls by Government security agencies. For establishing connectivity to Centralized Monitoring System, the Licensee at its own cost shall provide appropriately dimensioned hardware and bandwidth/dark fibre upto a designated point as required by Licensor from time to time. In case the security agencies intend to locate the equipment at Licensee’s premises for facilitating monitoring, the Licensee should extend all support in this regard including space and entry of the authorized security personnel.

The Interface requirements as well as features and facilities as defined by the Licensor should be implemented by the Licensee for both data and speech. The Licensee should ensure suitable redundancy in the complete chain of Lawful Interception and Monitoring equipment for trouble free operations of monitoring of at least 480 simultaneous calls as per requirement with at least 30 simultaneous calls for each of the designated security/ law enforcement agencies. Each MSC of the Licensee in the service area shall have the capacity for provisioning of at least 3000 numbers for monitoring. Presently there are ten (10) designated security/ law enforcement agencies. The above capacity provisions and no. of designated security/ law enforcement agencies may be amended by the Licensor separately by issuing instructions at any time.

Along with the monitored call following records are to be made available:

- Called/calling party mobile/PSTN numbers.

- Time/date and duration of interception.

- Location of target subscribers. Cell ID should be provided for location of the target subscriber. However, Licensor may issue directions from time to time on the precision of location, based on technological developments and integration of Global Positioning System (GPS) which shall be binding on the LICENSEE.

- Telephone numbers if any call-forwarding feature has been invoked by target subscriber.

- Data records for even failed call attempts.

- CDR (Call Data Record) of Roaming Subscriber.

The Licensee is required to provide the call data records of all the specified calls handled by the system at specified periodicity, as and when required by the security agencies.[97]

The call detail records for outgoing calls made by those subscribers making large number of outgoing calls day and night to the various telephone numbers with normally no incoming calls, is required to be analyzed by the Licensee. The service provider is required to run special programme, devise appropriate fraud management and prevention programme and fix threshold levels of average per day usage in minutes of the telephone connection; all telephone connections crossing the threshold of usage are required to be checked for bona fide use. A record of check must be maintained which may be verified by Licensor any time. The list/details of suspected subscribers should be informed to the respective TERM Cell of DoT and any other officer authorized by Licensor from time to time.[98]

The Licensee shall provide location details of mobile customers as per the accuracy and time frame mentioned in the Unified License. It shall be a part of CDR in the form of longitude and latitude, besides the co-ordinate of the BTS, which is already one of the mandated fields of CDR. To start with, these details will be provided for specified mobile numbers. However, within a period of 3 years from effective date of the Unified License, location details shall be part of CDR for all mobile calls.[99]

Internet Service: The Licensee is required to maintain CDR/IPDR for Internet including Internet Telephony Service for a minimum period of one year. The Licensee is also required to maintain log-in/log-out details of all subscribers for services provided such as internet access, e-mail, Internet Telephony, IPTV etc. These logs are to be maintained for a minimum period of one year. For the purpose of interception and monitoring of traffic, the copies of all the packets originating from / terminating into the Customer Premises Equipment (CPE) shall be made available to the Licensor/Security Agencies. Further, the list of Internet Lease Line (ILL) customers is to be placed on a password protected website in the format prescribed in the Unified License.[100]

Lawful Interception and Monitoring (LIM) systems of requisite capacities are to be set up by the Licensees for Internet traffic including Internet telephony traffic through their Internet gateways and /or Internet nodes at their own cost, as per the requirement of the security agencies/Licensor prescribed from time to time. The cost of maintenance of the monitoring equipment and infrastructure at the monitoring centre located at the premises of the licensee shall be borne by the Licensee. In case the Licensee obtains Access spectrum for providing Internet Service / Broadband Wireless Access using the Access Spectrum, the Licensee shall install the required Lawful Interception and Monitoring systems of requisite capacities prior to commencement of service. The Licensee, while providing downstream Internet bandwidth to an Internet Service provider is also required to ensure that all the traffic of downstream ISP passing through the Licensee’s network can be monitored in the network of the Licensee. However, for nodes of Licensee having upstream bandwidth from multiple service providers, the Licensee may be mandated to install LIM/LIS at these nodes, as per the requirement of security agencies. In such cases, upstream service providers may not be required to monitor this bandwidth.[101]

In case the Licensee has multiple nodes/points of presence and has capability to monitor the traffic in all the Routers/switches from a central location, the Licensor may accept to monitor the traffic from the said central monitoring location, provided that the Licensee is able to demonstrate to the Licensor/Security Agencies that all routers / switches are accessible from the central monitoring location. Moreover, the Licensee would have to inform the Licensor of every change that takes place in their topology /configuration, and ensure that such change does not make any routers/switches inaccessible from the central monitoring location. Further, Office space of 10 feet x 10 feet with adequate and uninterrupted power supply and air-conditioning which is physically secured and accessible only to the monitoring agencies shall be provided by the Licensee at each Internet Gateway location at its cost.[102]

National Long Distance (NLD) Service: The requisite monitoring facilities are required to be provided by the Licensee as per requirement of Licensor. The details of leased circuit provided by the Licensee is to be provided monthly to security agencies & DDG (TERM) of the Licensed Service Area where the licensee has its registered office.[103]

International Long Distance (ILD) Service: Office space of 20’x20’ with adequate and uninterrupted power supply and air-conditioning which is physically secured and accessible only to the personnel authorized by the Licensor is required to be provided by the Licensee at each Gateway location free of cost.[104] The cost of monitoring equipment is to be borne by the Licensee. The installation of the monitoring equipment at the ILD Gateway Station is to be done by the Licensee. After installation of the monitoring equipment, the Licensee shall get the same inspected by monitoring /security agencies. The permission to operate/commission the gateway will be given only after this.[105]

The designated person of the Central/ State Government, in addition to the Licensor or its nominee, has the right to monitor the telecommunication traffic in every ILD Gateway / Routers or any other technically feasible point in the network set up by the Licensee. The Licensee is required to make arrangement for monitoring simultaneous calls by Government security agencies. For establishing connectivity to Centralized Monitoring System, the Licensee, at its own cost, is required to provide appropriately dimensioned hardware and bandwidth/dark fibre upto a designated point as required by Licensor from time to time. In case the security agencies intend to locate the equipment at Licensee’s premises for facilitating monitoring, the Licensee should extend all support in this regard including Space and Entry of the authorized security personnel. The Interface requirements as well as features and facilities as defined by the Licensor should be implemented by the Licensee for both data and speech. The Licensee should ensure suitable redundancy in the complete chain of Monitoring equipment for trouble free operations of monitoring of at least 480 simultaneous calls as per requirement with at least 30 simultaneous calls for each of the designated security/ law enforcement agencies. Each ILD Gateway of the Licensee shall have the capacity for provisioning of at least 5000 numbers for monitoring. Presently there are ten (10) designated security/ law enforcement agencies. The above capacity provisions and number of designated security/ law enforcement agencies may be amended by the Licensor separately by issuing instructions at any time.[106]

The Licensee is required to provide the call data records of all the specified calls handled by the system at specified periodicity, as and when required by the security agencies in the format prescribed from time to time.[107]

Global Mobile Personal Communication by Satellite (GMPCS) Service: The designated Authority of the Central/State Government shall have the right to monitor the telecommunication traffic in every Gateway set up in India. The Licensee shall make arrangement for monitoring of calls as specified in the Unified License.[108]

The hardware/software required for monitoring of calls shall be engineered, provided/installed and maintained by the Licensee at the ICC (Intercept Control Centre) to be established at the GMPCS Gateway(s) as also in the premises of security agencies at Licensee’s cost. The Interface requirements as well as features and facilities shall be worked out and implemented by the Licensee for both data and speech. The Licensee should ensure suitable redundancy in the complete chain of Monitoring equipment for trouble free operations. The Licensee shall provide suitable training to the designated representatives of the Licensor regarding operation and maintenance of Monitoring equipment (ICC & MC). Interception of target subscribers using messaging services should also be provided even if retrieval is carried out using PSTN links. For establishing connectivity to Centralized Monitoring System, the Licensee at its own cost shall provide appropriately dimensioned hardware and bandwidth/dark fibre upto a designated point as required by Licensor from time to time.[109] The License also has specific obligations to extend monitored calls to designated security agencies as provided in the UL.[110] Further, the Licensee is required to provide the call data records of all the calls handled by the system at specified periodicity, if and as and when required by the security agencies.[111] It is the responsibility of the service provider for Global Mobile Personal Communication by Satellite (GMPCS) to provide facility to carry out surveillance of User Terminal activity.[112]

The Licensee has to make available adequate monitoring facility at the GMPCS Gateway in India to monitor all traffic (traffic originating/terminating in India) passing through the applicable system. For this purpose, the Licensee shall set up at his cost, the requisite interfaces, as well as features and facilities for monitoring of calls by designated agencies as directed by the Licensor from time to time. In addition to the Target Intercept List (TIL), it should also be possible to carry out specific geographic location based interception, if so desired by the designated security agencies. Monitoring of calls should not be perceptible to mobile users either during direct monitoring or when call has been grounded for monitoring. The Licensee shall not prefer any charges for grounding a call for monitoring purposes. The intercepted data is to be pushed to designated Security Agencies’ server on fire and forget basis. No records shall be maintained by the Licensee regarding monitoring activities and air-time used beyond prescribed time limit.

The Licensee has to ensure that any User Terminal (UT) registered in the gateway of another country shall re-register with Indian Gateway when operating from Indian Territory. Any UT registered outside India, when attempting to make/receive calls from within India, without due authority, shall be automatically denied service by the system and occurrence of such attempts along with information about UT identity as well as location shall be reported to the designated authority immediately.

The Licensee is required to have provision to scan operation of subscribers specified by security/ law enforcement agencies through certain sensitive areas within the Indian territory and shall provide their identity and positional location (latitude and longitude) to Licensor on as and when required basis.

Public Mobile Radio Trunking Service (PMRTS): Suitable monitoring equipment prescribed by the Licensor for each type of System used has to be provided by the Licensee at his own cost for monitoring, as and when required.[113]

Very Small Aperture Terminal (VSAT) Closed User Group (CUG) Service: Requisite monitoring facilities/ equipment for each type of system used have to be provided by the Licensee at its own cost for monitoring as and when required by the Licensor.[114] The Licensee shall provide at its own cost technical facilities for accessing any port of the switching equipment at the HUB for interception of the messages by the designated authorities at a location to be determined by the Licensor.[115]

Surveillance of MSS-R Service: The Licensee has to provide at its own cost technical facilities for accessing any port of the switching equipment at the HUB for interception of the messages by the designated authorities at a location as and when required.[116] It is the responsibility of the service provider of INSAT- Mobile Satellite System Reporting (MSS-R) service to provide facility to carry out surveillance of User Terminal activity within a specified area.[117]

Resale of International Private Leased Circuit (IPLC) Service: The Licensee has to take IPLC from the licensed ILDOs. The interception and monitoring of Resellers circuits will take place at the Gateway of the ILDO from whom the IPLC has been taken by the Licensee. The provisioning for Lawful Interception & Monitoring of the Resellers’ IPLC shall be done by the ILD Operator and the concerned ILDO shall be responsible for Lawful Interception and Monitoring of the traffic passing through the IPLC. The Resellers shall extend all cooperation in respect of interception and monitoring of its IPLC and shall be responsible for the interception results. The Licensee shall be responsible to interact, correspond and liaise with the licensor and security agencies with regard to security monitoring of the traffic. The Licensee shall, before providing an IPLC to the customer, get the details of services/equipment to be connected on both ends of IPLC, including type of terminals, data rate, actual use of circuit, protocols/interface to be used etc. The Resellers shall permit only such type of service/protocol on the IPLC for which the concerned ILDO has capability of interception and monitoring. The Licensee has to pass on any direct request placed by security agencies on him for interception of the traffic on their IPLC to the concerned ILDOs within two hours for necessary actions.[118]

4. The Information Technology Act, 2000

The Information Technology Act, 2000, was amended in a major way in 2008 and is the primary legislation which regulates the interception, monitoring, decryption and collection of traffic information of digital communications in India.

More specifically, section 69 of the Information Technology Act empowers the central Government and the state governments to issue directions for the monitoring, interception or decryption of any information transmitted, received or stored through a computer resource. Section 69 of the Information Technology Act, 2000 expands the grounds upon which interception can take place as compared to the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885. As such, the interception of communications under Section 69 is carried out in the interest of[119]:

- The sovereignty or integrity of India

- Security of the State

- Friendly relations with foreign States

- Public order

- Preventing incitement to the commission of any cognizable offense relating to the above

- For the investigation of any offense

While the grounds for interception are similar to the Indian Telegraph Act (except for the condition of prevention of incitement of only cognizable offences and the addition of investigation of any offence) the Information Technology Act does not have the overarching condition that interception can only occur in the case of public emergency or in the interest of public safety.

Additionally, section 69 of the Act mandates that any person or intermediary who fails to assist the specified agency with the interception, monitoring, decryption or provision of information stored in a computer resource shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to seven years and shall be liable for a fine.[120]

Section 69B of the Information Technology Act empowers the Central Government to authorise the monitoring and collection of information and traffic data generated, transmitted, received or stored through any computer resource for the purpose of cyber security. According to this section, any intermediary who intentionally or knowingly fails to provide technical assistance to the authorised agency which is required to monitor and collection information and traffic data shall be punished with an imprisonment which may extend to three years and will also be liable to a fine.[121]

The main difference between Section 69 and Section 69B is that the first requires the interception, monitoring and decryption of all information generated, transmitted, received or stored through a computer resource when it is deemed “necessary or expedient” to do so, whereas Section 69B specifically provides a mechanism for all metadata of all communications through a computer resource for the purpose of combating threats to “cyber security”. Directions under Section 69 can be issued by the Secretary to the Ministry of Home Affairs, whereas directions under Section 69B can only be issued by the Secretary of the Department of Information Technology under the Union Ministry of Communications and Information Technology.

Overlap with the Telegraph Act

Thus while the Telegraph Act only allows for interception of messages or class of messages transmitted by a telegraph, the Information Technology Act enables interception of any information being transmitted or stored in a computer resource. Since a “computer resource” is defined to include a communication device (such as cellphones and PDAs) there is a overlap between the provisions of the Information Technology Act and the Telegraph Act concerning the provisions of interception of information sent through mobile phones. This is further complicated by the fact that the UAS License specifically states that it is governed by the provisions of the Indian Telegraph Act, the Indian Wireless Telegraphy Act and the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Act, but does not mention the Information Technology Act.[122] This does not mean that the Licensees under the Telecom Licenses are not bound by any other laws of India (including the Information Technology Act) but it is just an invitation to unnecessary complexities and confusions with regard to a very serious issue such as interception. This situation has thankfully been remedied by the Unified License (UL) which, although issued under section of 4 of the Telegraph Act, also references the Information Technology Act thus providing essential clarity with respect to the applicability of the Information Technology Act to the License Agreement.

Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009

The interception of internet communications is mainly covered by the Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Interception, Monitoring and Decryption of Information) Rules, 2009under the Information Technology Act (the “IT Interception Rules”). In particular, the rules framed under Section 69 and 69B include safeguards stipulating to who may issue directions of interception and monitoring, how such directions are to be executed, the duration they remain in operation, to whom data may be disclosed, confidentiality obligations of intermediaries, periodic oversight of interception directions by a Review Committee under the Indian Telegraph Act, the retention of records of interception by intermediaries and to the mandatory destruction of information in appropriate cases.

According to the IT Interception Rules, only the competent authority can issue an order for the interception, monitoring or decryption of any information generated, transmitted, received or stored in any computer resource under sub-section (2) of section 69 of the Information Technology Act.[123] At the State and Union Territory level, the State Secretaries respectively in charge of the Home Departments are designated as “competent authorities” to issue interception directions.[124] In unavoidable circumstances the Joint Secretary to the Government of India, when so authorised by the Competent Authority, may issue an order. Interception may also be carried out with the prior approval of the Head or the second senior most officer of the authorised security agency at the Central Level and at the State Level with the approval of officers authorised in this behalf not below the rank of Inspector General of Police, in the belowmentioned emergent cases:

(1) in remote areas, where obtaining of prior directions for interception or monitoring or decryption of information is not feasible; or

(2) for operational reasons, where obtaining of prior directions for interception or monitoring or decryption of any information generation, transmitted, received or stored in any computer resource is not feasible,

however, in the above circumstances the officer would have to inform the competent authority in writing within three working days about the emergency and of the interception, monitoring or decryption and obtain the approval of the competent authority within a period of seven working days. If the approval of the competent authority is not obtained within the said period of seven working days, such interception or monitoring or decryption shall cease and the information shall not be intercepted or monitored or decrypted thereafter without the prior approval of the competent authority.[125] If a state wishes to intercept information that is beyond its jurisdiction, it must request permission to issue the direction from the Secretary in the Ministry of Home Affairs.[126]

In order to avoid the risk of unauthorised interception, the IT Interception Rules provide for the following safeguards:

- If authorised by the competent authority, any agency of the government may intercept, monitor, or decrypt information transmitted, received, or stored in any computer resource only for the purposes specified in section 69(1) of the IT Act.[127]

- The IT Interception Rules further provide that the competent authority may give any decryption direction to the decryption key holder.[128]

- The officer issuing an order for interception is required to issue requests in writing to designated nodal officers of the service provider.[129]

- Any direction issued by the competent authority must contain the reasons for direction, and must be forwarded to the review committee seven days after being issued.[130]

- In the case of issuing or approving an interception order, in arriving at its decision the competent authority must consider all alternate means of acquiring the information.[131]

- The order must relate to information sent or likely to be sent from one or more particular computer resources to another (or many) computer resources.[132]

- The reasons for ordering interceptions must be recorded in writing, and must specify the name and designation of the officer to whom the information obtained is to be disclosed, and also specify the uses to which the information is to be put.[133]

- The directions for interception will remain in force for a period of 60 days, unless renewed. If the orders are renewed they cannot be in force for longer than 180 days.[134]

- Authorized agencies are prohibited from using or disclosing contents of intercepted communications for any purpose other than investigation, but they are permitted to share the contents with other security agencies for the purpose of investigation or in judicial proceedings. Furthermore, security agencies at the union territory and state level will share any information obtained by following interception orders with any security agency at the centre.[135]

- All records, including electronic records pertaining to interception are to be destroyed by the government agency “every six months, except in cases where such information is required or likely to be required for functional purposes”.[136]

- The contents of intercepted, monitored, or decrypted information will not be used or disclosed by any agency, competent authority, or nodal officer for any purpose other than its intended purpose.[137]

- The agency authorised by the Secretary of Home Affairs is required to appoint a nodal officer (not below the rank of superintendent of police or equivalent) to authenticate and send directions to service providers or decryption key holders.[138]

The IT Interception Rules also place the following obligations on the service providers:

- In addition, all records pertaining to directions for interception and monitoring are to be destroyed by the service provider within a period of two months following discontinuance of interception or monitoring, unless they are required for any ongoing investigation or legal proceedings.[139]

- Upon receiving an order for interception, service providers are required to provide all facilities, co-operation, and assistance for interception, monitoring, and decryption. This includes assisting with: the installation of the authorised agency's equipment, the maintenance, testing, or use of such equipment, the removal of such equipment, and any action required for accessing stored information under the direction.[140]

- Additionally, decryption key holders are required to disclose the decryption key and provide assistance in decrypting information for authorized agencies.[141]

- Every fifteen days the officers designated by the intermediaries are required to forward to the nodal officer in charge a list of interceptions orders received by them. The list must include the details such as reference and date of orders of the competent authority.[142]

- The service provider is required to put in place adequate internal checks to ensure that unauthorised interception does not take place, and to ensure the extreme secrecy of intercepted information is maintained.[143]

- The contents of intercepted communications are not allowed to be disclosed or used by any person other than the intended recipient.[144]

- Additionally, the service provider is required to put in place internal checks to ensure that unauthorized interception of information does not take place and extreme secrecy is maintained. This includes ensuring that the interception and related information are handled only by the designated officers of the service provider.[145]

Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Monitoring and Collecting Traffic Data or Information) Rules, 2009

The Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Monitoring and Collecting Traffic Data or Information) Rules, 2009, under section 69B of the Information Technology Act, stipulate that directions for the monitoring and collection of traffic data or information can be issued by an order made by the competent authority[146] for any or all of the following purposes related to cyber security:

- forecasting of imminent cyber incidents;

- monitoring network application with traffic data or information on computer resource;

- identification and determination of viruses or computer contaminant;

- tracking cyber security breaches or cyber security incidents;

- tracking computer resource breaching cyber security or spreading virus or computer contaminants;

- identifying or tracking any person who has breached, or is suspected of having breached or likely to breach cyber security;

- undertaking forensic of the concerned computer resource as a part of investigation or internal audit of information security practices in the computer resources;

- accessing stored information for enforcement of any provisions of the laws relating to cyber security for the time being in force;

- any other matter relating to cyber security.[147]

According to these Rules, any direction issued by the competent authority should contain reasons for such direction and a copy of such direction should be forwarded to the Review Committee within a period of seven working days.[148] Furthermore, these Rules state that the Review Committee shall meet at least once in two months and record its finding on whether the issued directions are in accordance with the provisions of sub-section (3) of section 69B of the Act. If the Review Committee is of the opinion that the directions are not in accordance with the provisions referred to above, it may set aside the directions and issue an order for the destruction of the copies, including corresponding electronic record of the monitored or collected traffic data or information.[149]

Information Technology (Guidelines for Cyber Cafes) Rules, 2011

The Information Technology (Guidelines for Cyber Cafes) Rules, 2011, were issued under powers granted under section 87(2), read with section 79(2) of the Information Technology Act, 2000.[150] These rules require cyber cafes in India to store and maintain backup logs for each login by any user, to retain such records for a year and to ensure that the log is not tampered. Rule 7 requires the inspection of cyber cafes to determine that the information provided during registration is accurate and remains updated.

5. The Indian Post Office Act, 1898

Section 26 of the Indian Post Office Act, 1898, empowers the Central Government and the State Governments to intercept postal articles.[151] In particular, section 26 of the Indian Post Office Act, 1898, states that on the occurrence of any public emergency or in the interest of public safety or tranquility, the Central Government, State Government or any officer specially authorised by the Central or State Government may direct the interception, detention or disposal of any postal article, class or description of postal articles in the course of transmission by post. Furthermore, section 26 states that if any doubt arises regarding the existence of public emergency, public safety or tranquility then a certificate to that effect by the Central Government or a State Government would be considered as conclusive proof of such condition being satisfied.

According to this section, the Central Government and the State Governments of India can intercept postal articles if it is deemed to be in the instance of a 'public emergency' or for 'public safety or tranquility'. However, the Indian Post Office Act, 1898, does not cover electronic communications and does not mandate their interception, which is covered by the Information Technology Act, 2000 and the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885.

6. The Indian Wireless Telegraphy Act, 1933

The Indian Wireless Telegraphy Act was passed to regulate and govern the possession of wireless telegraphy equipment within the territory of India. This Act essentially provides that no person can own “wireless telegraphy apparatus”[152] except with a license provided under this Act and must use the equipment in accordance with the terms provided in the license.[153]

One of the major sources of revenue for the Indian State Broadcasting Service was revenue from the licence fee from working of wireless apparatus under the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885.The Indian State Broadcasting Service was losing revenue due to lack of legislation for prosecuting persons using unlicensed wireless apparatus as it was difficult to trace them at the first place and then prove that such instrument has been installed, worked and maintained without licence. Therefore, the current legislation was proposed, in order to prohibit possession of wireless telegraphy apparatus without licence.

Presently the Act is used to prosecute cases, related to illegal possession and transmission via satellite phones. Any person who wishes to use satellite phones for communication purposes has to get licence from the Department of Telecommunications.[154]

7. The Code of Criminal Procedure

Section 91 of the Code of Criminal Procedure regulates targeted surveillance. In particular, section 91 states that a Court in India or any officer in charge of a police station may summon a person to produce any document or any other thing that is necessary for the purposes of any investigation, inquiry, trial or other proceeding under the Code of Criminal Procedure.[155] Under section 91, law enforcement agencies in India could theoretically access stored data. Additionally, section 92 of the Code of Criminal Procedure regulates the interception of a document, parcel or thing in the possession of a postal or telegraph authority.

Further section 356(1) of the Code of Criminal Procedure provides that in certain cases the Courts have the power to direct repeat offenders convicted under certain provisions, to notify his residence and any change of, or absence from, such residence after release for a term not exceeding five years from the date of the expiration of the second sentence.

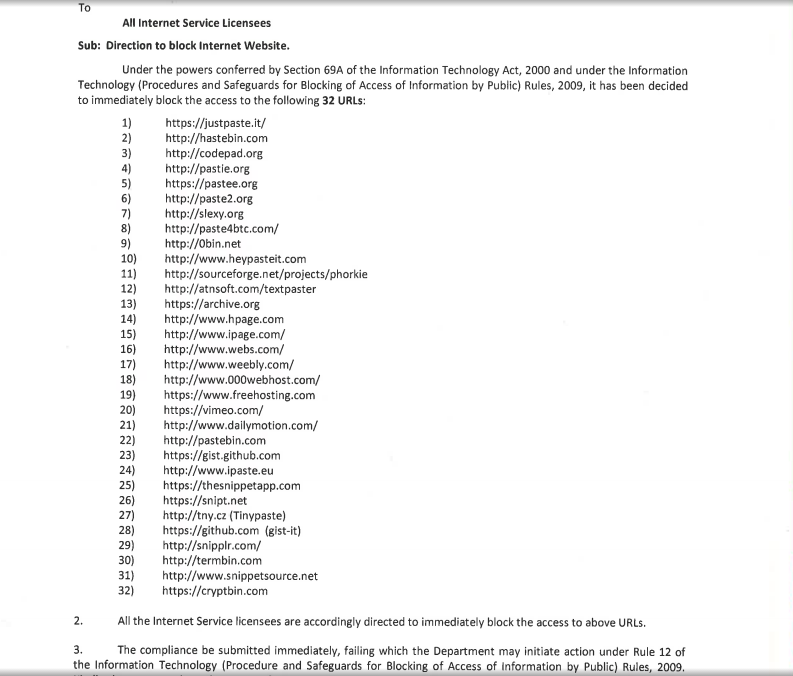

Policy Suggestions