Blog

Indian Intermediary Liability Regime: Compliance with the Manila Principles on Intermediary Liability

The report was edited by Elonnai Hickok and Swaraj Barooah

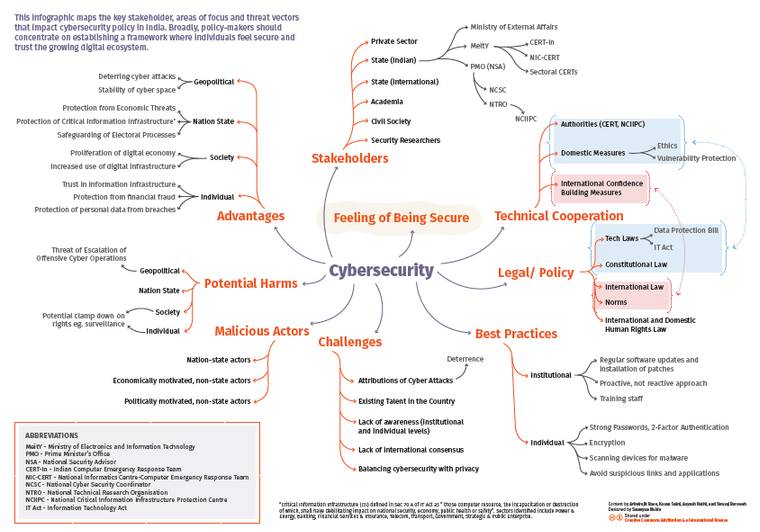

The report is an examination of Indian laws based upon the background paper to the Manila Principles as the explanatory text on which these recommendations have been based, and not an assessment of the principles themselves. To do this, the report considers the Indian regime in the context of each of the principles defined in the Manila Principles. As such, the explanatory text to the Manila Principles recognizes that diverse national and political scenario may require different intermediary liability legal regimes, however, this paper relies only on the best practices prescribed under the Manila Principles.

The report is divided into the following sections

- Principle I: Intermediaries should be shielded by law from liability for third-party content

- Principle II: Content must not be required to be restricted without an order by a judicial authority

- Principle III: Requests for restrictions of content must be clear, be unambiguous, and follow due process

- Principle IV: Laws and content restriction orders and practices must comply with the tests of necessity and proportionality

-

Principle V: Laws and content restriction policies and practices must respect due process

-

Principle VI: Transparency and accountability must be built into laws and content restriction policies and practices

-

Conclusion

DIDP Request #30 - Employee remuneration structure at ICANN

We have requested ICANN to disclose information pertaining to the income of each employee based on the following grounds. We had hoped this information will increase ICANN's transparency regarding their remuneration policies however ths was not the case, they either referred to their earlier documents who do not have concrete information or stated that the relevant documents were not in their possession. Their response to the respective questions were:

Average salary across designations

ICANN responded by referring to their FY18 Remuneration Practices document which states, “ICANN uses a global compensation expert consulting firm to provide comprehensive benchmarking market data (currently Willis Towers Watson, Mercer and Radford). The market study is conducted before the salary review process. Estimates of potential compensation adjustments typically are made during the budgeting process based on current market data. The budget is then approved as part of ICANN’s overall budget planning process.”

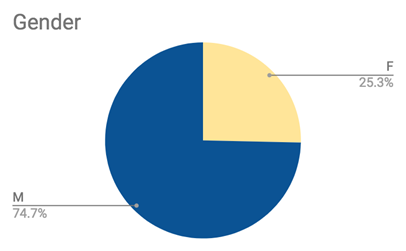

Average salary for female and male employees

ICANN responded by saying “ICANN org’s remuneration philosophy and practice is not based upon gender” which is why they said that they have “no documentary information in ICANN org’s possession, custody or control that is responsive to this request.” However, the exact average salaries of female and male employees was not provided nor any information that could that could give us an idea as to whether the remuneration of their employees was in accordance with the above claim.

Bonuses - frequency at which it is given and upon what basis

ICANN responded by referring to “Discretionary At-Risk Component” section in their FY18 Remuneration Practices document which states,”The amount of at-risk pay an individual can earn is based on a combination of both the achievement of goals as well as the behaviors exhibited in achieving those goals… The Board has approved a framework whereby those with ICANN Org are eligible to earn an at-risk payment of up to 20 percent of base compensation as at-risk payment based on role and level in the organization, with certain senior executives eligible for up to 30 percent.” The duration over which the employees are eligible to receive an “at-risk” payment was given to be “twice a year".

Average salary across regions for the same region

ICANN responded by saying,”compensation may vary across the regions based on currency differences, the availability of positions in a given region, market conditions, as well as the type of positions that are available in a given region. “ They also added that they have no documentary information in their possession, custody or control that is responsive to this request.

The request filed by Paul Kurian may be found here. ICANN's response can be read here.

Design Concerns in Creating Privacy Notices

This blog post was edited by Elonnai Hickok.

The Role of Design in Enabling Informed Consent

Currently, privacy notices and choice mechanisms, are largely ineffective. Privacy and security researchers have concluded that privacy notices not only fail to help consumers make informed privacy decisions but are mostly ignored by them. [1] They have been reduced to being a mere necessity to ensure legal compliance for companies. The design of privacy systems has an essential role in determining whether the users read the notices and understand them. While it is important to assess the data practices of a company, the communication of privacy policies to users is also a key factor in ensuring that the users are protected from privacy threats. If they do not read or understand the privacy policy, they are not protected by it at all.

The visual communication of a privacy notice is determined by the User Interface (UI) and User Experience (UX) design of that online platform. User experience design is broadly about creating the logical flow from one step to the next in any digital system, and user interface design ensures that each screen or page that the user interacts with has a consistent visual language and styling. This compliments the path created by the user experience designer. [2] UI/UX design still follows the basic principles of visual communication where information is made understandable, usable and interesting with the use of elements such as colours, typography, scale, and spacing.

In order to facilitate informed consent, the design principles are to be applied to ensure that the privacy policy is presented clearly, and in the most accessible form. A paper by Batya Friedman, Peyina Lin, and Jessica K. Miller, ‘Informed Consent By Design’, presents a model of informed consent for information systems. [3] It mentions the six components of the model; Disclosure, Comprehension, Voluntariness, Competence, Agreement, Minimal Distraction. The design of a notice should achieve these components to enable informed consent. Disclosure and comprehension lead to the user being ‘informed’ while ‘consent’ encompasses voluntariness, competence, and agreement. Finally, The tasks of being informed and giving consentshould happen with minimal distraction, without diverting users from their primary taskor overwhelming them with unnecessary noise.[4]

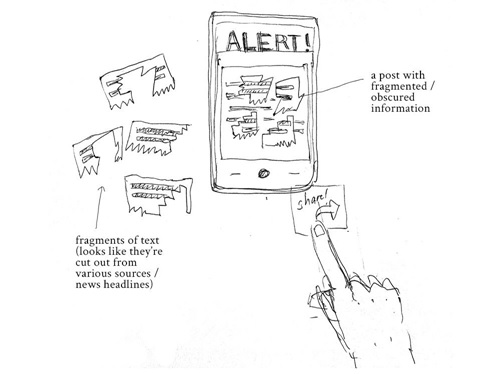

UI/UX design builds upon user behaviour to anticipate their interaction with the platform. It has led to practices where the UI/UX design is directed at influencing the user to respond in a way that is desired by the system. For instance, the design of default options prompts users to allow the system to collect their data when the ‘Allow’ button is checked by default. Such practices where the interface design is used to push users in a particular direction are called “dark patterns”.[5] These are tricks used in websites and apps that make users buy or sign up for things that they did not intend to. [6] Dark patterns are often followed as UI/UX trends without the consequences on users being questioned. This has had implications on the design of privacy systems as well. Privacy notices are currently being designed to be invisible instead of drawing attention towards them.

Moreover, most communication designers believe that privacy notices are beyond their scope of expertise. They do not consider themselves accountable for how a notice comes across to the user. Designers also believe that they have limited agency when it comes to designing privacy notices as most of the decisions have been already taken by the company or the service. They can play a major role in communicating privacy concerns at an interface level, but the issues of privacy are much deeper. Designers tend to find ways of informing the user without compromising the user experience, and in the process choose aesthetic decisions over informed consent.

Issues with Visual Communication of Privacy Notices

The ineffectiveness of privacy notices can be attributed to several broad issues such as the complex language and length, their timing, and location. In 2015, the Center for Plain Language [7] published a privacy-policy analysis report [8] for TIME.com [9], evaluating internet-based companies’ privacy policies to determine how well they followed plain language guidelines. The report concluded that among the most popular companies, Google and Facebook had the more accessible notices, while Apple, Uber, and Twitter were ranked as less accessible. The timing of notices is also crucial in ensuring that it is read by the users. The primary task for the user is to avail the service being offered. The goals of security and privacy are valued but are only secondary in this process. [10] Notices are presented at a time when they are seen as a barrier between the user and the service. People thus, choose to ignore the notices and move on to their primary task. Another concern is disassociated notices or notices which are presented on a separate website or manual. The added effort of going to an external website also gets in the way of the users which leads to them not reading the notice. While most of these issues can be dealt with at the strategic level of designing the notice, there are also specific visual communication design issues that are required to be addressed.

Invisible Structure and Organisation of Information

Long spells of text with no visible structure or content organisation is the lowest form of privacy notices. These are the blocks of text where the information is flattened with no visual markers such as a section separator, or contrasting colour and typography to distinguish between the types of content. In such notices, the headings and subheadings are also not easy to locate and comprehend. For a user, the large block of text appears to be pointless and irrelevant, and they begin to dismiss or ignore it. Further, the amount of time it would take for the user to read the entire text and comprehend it successfully, is simply impractical, considering the number of websites they visit regularly.

The privacy policy notice by Apple [11] with no use of colours or visuals.

The privacy policy notice by Twitter [12] no visual segregator

Visual Contrast Between Front Interface and Privacy Notices

The front facing interface of an app or website is designed to be far more engaging than the privacy notice pages. There is a visible difference in the UI/UX design of the pages, almost as if the privacy notices were not designed at all. In case of Uber’s mobile app, the process of adding a destination, selecting the type of cab and confirming a ride has been made simple to do for any user. This interface has been thought through keeping in mind the users’ behaviour and needs. It allows for quick and efficient use of the service. As opposed to the process of buying into the service, the privacy notice on the app is complex and unclear.

Uber mobile app screenshots of the front interface (left) and the policy notice page (right)

Gaining Trust Through the Initial Pitch

A pattern in the privacy notices of most companies is that they attempt to establish credibility and gain confidence by stating that they respect the users’ privacy. This can be seen in the introductory text of the privacy notices of Apple and LinkedIn. The underlying intent seems to be that since the company understands that the users’ privacy is important, the users can rely on them and not read the full notice.

Introduction text to Apple’s privacy policy notice [13]

Introduction text to LinkedIn’s privacy policy notice [14]

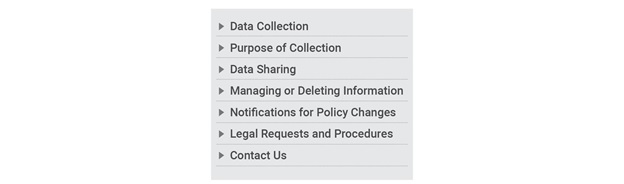

Low Navigability

The text heavy notices need clear content pockets which can be navigated through easily using mechanisms such as menu bar. Navigability of a document allows for quick locating of sections, and moving between them. Several companies miss to follow this. Apple and Twitter privacy notices (shown above), have low navigability as the reader has no prior indication of how many sections there are in the notice. The reader could have summarised the content based on the titles of the sections if it were available in a table of contents or a menu. Lack of a navigation system leads to endless scrolling to reach the end of the page.

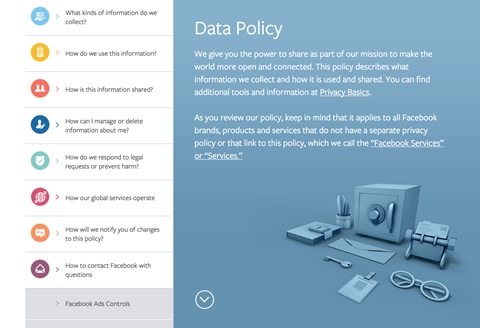

Facebook privacy notice, on the other hand is an example of good navigability. It uses typography and colour to build a clear structure of information that can be navigated through easily using the side menu. The menu doubles up as a table of contents for the reader. The side menu however, does not remain visible while scrolling down the page. This means while the user is reading through a section, they cannot switch to a different section from the menu directly. They will need to click on the ‘Return to top’ button and then select the section from the menu.

Navigation menu in the Facebook Data Policy page [15]

Lack of Visual Support

Privacy notices can rely heavily on visuals to convey the policies more efficiently. These could be visual summaries or supporting infographics. The data flow on the platform and how it would affect the users can be clearly visualised using infographics. But, most notices fail to adopt them. The Linkedin privacy notice [16] page shows a video at the beginning of its privacy policy. Although this could have been an opportunity to explain the policy in the video, LinkedIn only gives an introduction to the notice and follows it with a pitch to use the platform. The only visual used in notices currently are icons. Facebook uses icons to identify the different sections so that they can be located easily. But, apart from being identifiers of sections, these icons do not contribute to the communication of the policy. It does not make reading of the full policy any easier.

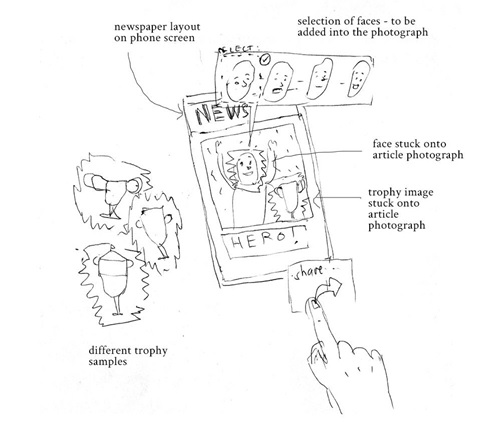

Icon Heavy ‘Visual’ Privacy Notices

The complexity of privacy notices has led to the advent of online tools and generators that create short notices or summaries for apps and websites to supplement the full text versions of policies. Most of these short notices use icons as a way of visually depicting the categories of data that is being collected and shared. iubenda [17], an online tool, generates policy notice summary and full text based on the inputs given by the client. It asks for the services offered by the site or app, and the type of data collection. Icons are used alongside the text headings to make the summary seem more ‘visual’ and hence more easily consumable. It makes the summary more inviting to read, but does not reduce the time for reading.

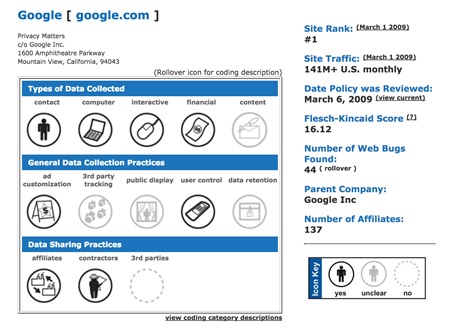

Another icon-based policy summary generator was created by KnowPrivacy. [18] They developed a policy coding methodology by creating icon sets for types of data collected, general data practices, and data sharing. The use of icons in these short notices is more meaningful as they show which type of data is collected or not collected, shared or not shared at a glance without any text. This facilitates comparison between data practices of different apps.

Icon based short policy notice created for Google by KnowPrivacy [19]

Initiatives to Counter Issues with the Design of Privacy Notices

Several initiatives have called out the issues with privacy notices and some have even countered them with tools and resources. The TIME.com ranking of internet-based companies’ privacy policies brought attention to the fact that some of the most popular platforms have ineffective policy notices. A user rights initiative called Terms of Services; Didn’t Read [20] rates and labels websites’ terms & privacy policies. There is also the Usable Privacy Policy Project which develops techniques to semi-automatically analyze privacy policies with crowdsourcing, natural language processing, and machine learning. [21] It uses artificial intelligence to sift through the most popular sites on the Internet, including Facebook, Reddit, and Twitter, and annotate their privacy policies. They realise that it is not practical for people to read privacy policies. Thus, their aim is to use technology to extract statements from the notices and match them with things that people care about. However, even AI has not been fully successful in making sense of the dense documents and missed out some important context. [22]

One of the more provocative initiatives is the Me and My Shadow ‘Lost in Small Print’ [23] project. It shows the text for the privacy notices of companies like LinkedIn, Facebook, WhatsApp, etc. and then ‘reveals’ the data collection and use information that would closely affect the users.

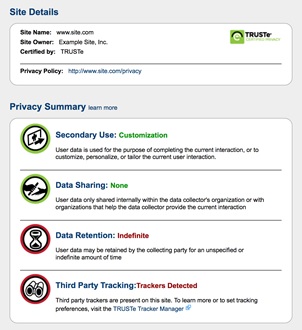

Issues with notices have also been addressed by standardising their format, so people can interpret the information faster. The Platform for Privacy Preferences Project (P3P) [24] was one of the initial efforts in enabling websites to share their privacy practices in a standard format. Similar to KnowPrivacy’s policy coding, there are more design initiatives that are focusing on short privacy notice design. An organisation offering services in Privacy Compliance and Risk Management Solutions called TrustArc, [25] is also in the process of designing an interactive icon-based privacy short notice.

TrustArc’s proposed design [26] for the short notice for a sample site

Most efforts have been done in simplifying the notices so as to decode the complex terminology. But, there have been very few evaluations and initiatives to improve the design of these notices.

Recommendations

Multilayered Privacy Notices

One of the existing suggestions on increasing usability of privacy notices are multilayered privacy notices. [27] Multilayered privacy notices comprise a very short notice designed for use on portable digital devices where there is limited space, condensed notice that contains all the key factors in an easy to understand way, and a complete notice with all the legal requirements. [28] Some of the examples above use this in the form of short notices and summaries. The very short notice layer consists of who is collecting the information, primary uses of information, and contact details of the organisation.[29] Condensed notice layer covers scope or who does the notice apply to, personal information collected, uses and sharing, choices, specific legal requirements if any, and contact information. [30] In order to maintain consistency, the sequence of topics in the condensed and the full notice must be same. Words and phrases should also be consistent in both layers. Although an effective way of simplifying information, multi-layered notices must be reconsidered along with the timing of notices. For instance, it could be more suitable to show very short notices at the time of collection or sharing of user data.

Supporting Infographics

Based on their visual design, the currently available privacy notices can be broadly classified into 4 categories; (i) the text only notices which do not have a clearly visible structure, (ii) the text notices with a contents menu that helps in informing of the structure and in navigating, (iii) the notices with basic use of visual elements such as icons used only to identify sections or headings, (iv) multilayered notices or notices with short summary before giving out the full text. There is still a lack of visual aid in all these formats. The use of visuals in the form of infographics to depict data flows could be more helpful for the users both in short summaries and complete text of policy notices.

Integrating the Privacy Notices with the Rest of the System

The design of privacy notices usually seems disconnected to the rest of the app or website. The UI/UX design of privacy notices requires as much attention as the consumer-facing interface of a system. The contribution of the designer has to be more than creating a clean layout for the text of the notice. The integration of privacy notices with the rest of the system is also related to the early involvement of the designer in the project. The designer needs to understand the information flows and data practices of a system in order to determine whether privacy notices are needed, who should be notified, and about what. This means that decisions such as selecting the categories to be represented in the short or condensed notice, the datasets within these categories, and the ways of representing them would all be part of the design process. The design interventions cannot be purely visual or UI/UX based. They need to be worked out keeping in mind the information architecture, content design, and research. By integrating the notices, strategic decisions on the timing and layering of content can be made as well, apart from the aesthetic decisions. Just as the aim of the front face of the interface in a system makes it easier for the user to avail the service, the policy notice should also help the user in understanding the consequences, by giving them clear notice of the unexpected collection or uses of their data.

Practice Based Frameworks on Designing Privacy Notices

There is little guidance available to communication designers for the actual design of privacy notices which is specific to the requirements and characteristics of a system. [31] The UI/UX practice needs to be expanded to include ethical ways of designing privacy notices online. The paper published by Florian Schaub, Rebecca Balebako, Adam L. Durity, and Lorrie Faith Cranor, called, ‘A Design Space for Effective Privacy Notice’ in 2015 offers a comprehensive design framework and standardised vocabulary for describing privacy notice options. [32] The objective of the paper is to allow designers to use this framework and vocabulary in creating effective privacy notices. The design space suggested has four key dimensions, ‘timing’, ‘channel’, ‘modality’ and ‘control’. [33] It also provides options for each of these dimensions. For example, ‘timing’ options are ‘at setup’, ‘just in time’, ‘context-dependent’, ‘periodic’, ‘persistent’, and ‘on demand’. The dimensions and options in the design space can be expanded to accommodate new systems and interaction methods.

Considering the Diversity of Audiences

For the various mobile apps and services, there are multiple user groups who use them. The privacy notices are hence not targeted to one kind of an audience. There are diverse audiences who have different privacy preferences for the same system. [34] The privacy preferences of these diverse groups of users’ must be accommodated. In a typical design process for any system, multiple user personas are identified. The needs and behaviour of each persona is used to determine the design of the interface. Privacy preferences must also be observed as part of these considerations for personas, especially while designing the privacy notices. Different users may need different kinds of notices based on which data practices affect them.[35] Thus, rather than mandating a single mechanism for obtaining informed consent for all users in all situations, designers need to provide users with a range of mechanisms and levels of control. [36]

Ethical Framework for Design Practitioners

An ethical framework is required for design practitioners that can be followed at the level of both deciding the information flow and the experience design. With the prevalence of ‘dark patterns’, the visual design of notices is used to trick users into accepting it. Design ethics can play a huge role in countering such practices. Will Dayable, co-director at Squareweave, [37] a developer of web and mobile apps, suggests that UI/UX designers should “Design Like They’re (Users are) Drunk”. [38] He asks designers to imagine the user to be in a hurry and still allow them access to all the information necessary for making a decision. He concludes that good privacy UX and UI is about actually trying to communicate with users rather than trying to slip one past them. In principle, an ethical design practice would respect the rights of the users and proactively design to facilitate informed consent.

Reconceptualising Privacy Notices

Based on the above recommendations, a guiding sample for multilayered privacy notices has been created. Each system would need its own structure and mechanisms for notices, which are integrated with its data practice, audiences, and medium, but this sample notice provides basic guidelines for creating effective and accessible privacy notices. The aesthetic decisions would also vary based on the interface design of a system.

Sample Fixed Icon for Privacy Notifications

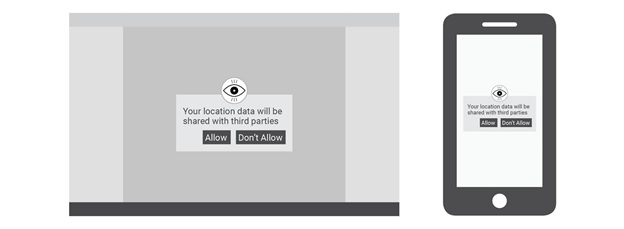

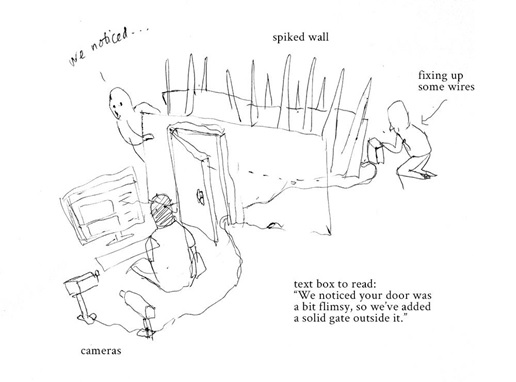

A fixed icon can appear along with all privacy notifications on the system, so that the users can immediately know that the notification is about a privacy concern. This icon should capture attention instantly and suggest a sense of caution. Besides its use as a call to attention, the icon can also lead to a side panel for privacy implications from all actions that the user takes.

Sample Very Short Notice on Desktop and Mobile Platforms

The very short notices can be shown when an action from the user would lead to data collection or sharing. The notice mechanism should be designed to provide notices at different times tailored to a user’s needs in that context. The styling and placement of the ‘Allow’ and ‘Don’t Allow’ buttons should not be biased towards the ‘Allow’ option. The text used in very short and condensed notice layers should be engaging yet honest in its communication.

Sample Summary Notice

The summary or the condensed notice layer should allow the user to gauge at a glance, how the data policy is going to affect them. This can be combined with a menu that lists the topics covered in the full notice. The menu would double up as a navigation mechanism for users. It should be visible to users even as they scroll down to the full notice. The condensed notice can also be supported by an infographic depicting the flow of data in the system.

Sample Navigation Menu

All the images in this section use sample text for the purpose of illustrating the structure and layout

The full notice can be made accessible by creating a clear information hierarchy in the text. The menu which is available on the side while scrolling down the text would facilitate navigation and familiarity with the structure of the notice.

Conclusion

The presentation of privacy notices directly influences the decisions of users online and ineffective notices make users vulnerable to their data being misused. But currently, there is little conversation about privacy and data protection among designers. Design practice has to become sensitive to privacy and security requirements. Designers need to take the accountability of creating accessible notices which are beneficial to the users, rather than to the companies issuing them. They must prioritise the well-being of users over aesthetics and user experience even. The aesthetics of a platform must be directed at achieving transparency in the privacy notice by making it easily readable.

The design community in India has a more urgent task at hand of building a design practice that is informed by privacy. Comparing the privacy notices of Indian and global companies, Indian companies have an even longer way to go in terms of communicating the notices effectively. Most Indian companies such as Swiggy, [39] 99acres, [40] and Paytm [41] have completely textual privacy policy notices with no clear information hierarchy or navigation. Ola Cabs [42] provides an external link to their privacy notice, which opens as a pdf, making it even more inaccessible. Thus, there is a complete lack of design input in the layout of these notices.

Designers must engage in conversations with technologists and researchers, and include privacy and other user rights in design education in order to prepare practitioners for creating more valuable digital platforms.

- https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_comments/2015/10/00038-97832.pdf

- https://www.fastcodesign.com/3032719/ui-ux-who-does-what-a-designers-guide-to-the-tech-industry

- https://vsdesign.org/publications/pdf/Security_and_Usability_ch24.pdf

- https://vsdesign.org/publications/pdf/Security_and_Usability_ch24.pdf

- https://fieldguide.gizmodo.com/dark-patterns-how-websites-are-tricking-you-into-givin-1794734134

- https://darkpatterns.org/

- https://centerforplainlanguage.org/

- https://centerforplainlanguage.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/TIME-privacy-policy-analysis-report.pdf

- http://time.com/3986016/google-facebook-twitter-privacy-policies/

- https://www.safaribooksonline.com/library/view/security-and-usability/0596008279/ch04.html

- https://www.apple.com/legal/privacy/en-ww/?cid=wwa-us-kwg-features-com

- https://twitter.com/privacy?lang=en

- https://www.apple.com/legal/privacy/en-ww/?cid=wwa-us-kwg-features-com

- https://www.linkedin.com/legal/privacy-policy

- https://www.facebook.com/privacy/explanation

- https://www.linkedin.com/legal/privacy-policy

- http://www.iubenda.com/blog/2013/06/13/privacypolicyforandroidapp/

- http://knowprivacy.org/policies_methodology.html

- http://knowprivacy.org/profiles/google

- https://tosdr.org/

- https://explore.usableprivacy.org/

- https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/a3yz4p/browser-plugin-to-read-privacy-policy-carnegie-mellon

- https://myshadow.org/lost-in-small-print

- https://www.w3.org/P3P/

- http://www.trustarc.com/blog/2011/02/17/privacy-short-notice-designpart-i-background/

- http://www.trustarc.com/blog/?p=1253

- https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_comments/2015/10/00038-97832.pdf

- https://www.informationpolicycentre.com/uploads/5/7/1/0/57104281/ten_steps_to_develop_a_multilayered_privacy_notice__white_paper_march_2007_.pdf

- https://www.informationpolicycentre.com/uploads/5/7/1/0/57104281/ten_steps_to_develop_a_multilayered_privacy_notice__white_paper_march_2007_.pdf

- https://www.informationpolicycentre.com/uploads/5/7/1/0/57104281/ten_steps_to_develop_a_multilayered_privacy_notice__white_paper_march_2007_.pdf

- https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_comments/2015/10/00038-97832.pdf

- https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_comments/2015/10/00038-97832.pdf

- https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_comments/2015/10/00038-97832.pdf

- https://www.safaribooksonline.com/library/view/security-and-usability/0596008279/ch04.html

- https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_comments/2015/10/00038-97832.pdf

- https://vsdesign.org/publications/pdf/Security_and_Usability_ch24.pdf

- https://www.squareweave.com.au/

- https://iapp.org/news/a/how-ui-and-ux-can-ko-privacy/

- https://www.swiggy.com/privacy-policy

- https://www.99acres.com/load/Company/privacy

- https://pages.paytm.com/privacy.html

- https://s3-ap-southeast-1.amazonaws.com/ola-prod-website/privacy_policy.pdf

CIS contributes to ABLI Compendium on Regulation of Cross-Border Transfers of Personal Data in Asia

The compendium contains 14 detailed reports written by legal practitioners, legal scholars and researchers in their respective jurisdictions, on the regulation of cross-border data transfers in the wider Asian region (Australia, China, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Macau SAR, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam).

The compendium is intended to act as a springboard for the next phase of ABLI's project, which will be devoted to the in-depth study of the differences and commonalities between Asian legal systems on these issues and – where feasible – the drafting of recommendations and/or policy options to achieve convergence in this area of law in Asia.

The chapter titled Jurisdictional Report India was authored by Amber Sinha and Elonnai Hickok. The compendium can be accessed here.

Comments on the Draft National Policy on Official Statistics

Edited by Swaraj Barooah. Download a PDF of the submission here

Preliminary

CIS appreciates the Government’s efforts in realising the importance of the need for high quality statistical information enshrined in the Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics as adopted by the UN General Assembly in January 2014. CIS is grateful for the opportunity to put forth its views on the draft policy. This submission was made on 31st May, 2018.

First, this submission highlights some general defects in the draft policy: there is lack of principles guiding data dissemination policies; there are virtually no positive mandates set for Government bodies for secure storage and transmission of data; and while privacy is mentioned as a concern, it has been overlooked in designing the principles of the implementation of surveys. Then, this submission puts forward specific comments suggesting improvements to various sections in the draft policy.

CIS would also like to point out the short timeline between the publication of the draft policy (18th May, 2018), and the deadline set for the stakeholders to submit their comments (31st May, 2018). Considering that the policy has widespread implications for all Ministries, citizens, and State legislation rights (proposed changes include a Constitutional Amendment), it is necessary that such call-for-comments are publicised widely, and enough time is given to the public so that the Government can receive well-researched comments.

General Comments

Data dissemination

For data dissemination, the draft policy does not stress upon a general principle or set of principles, and often disregards principles specified in the Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics, which are the very principles the Government intends to draw its policies on official statistics from. Rather it relies on context-specific provisions that fail to summarise and articulate a general philosophy for the dissemination of official statistics, and fails to practically embody some stated goals. The first principle on Official Statistics, as realised by the United Nations General Assembly, clearly states that: “[...] official statistics that meet the test of practical utility are to be compiled and made available on an impartial basis by official statistical agencies to honour citizens’ entitlement to public information.”

Let us compare this with Section 5.1.7 (9) of the draft policy, which refers to policies regarding core statistics: it mentions a data “warehouse” to be maintained by the NSO which should be accessible to private and public bodies. While this does point towards an open data policy, such a vision has not been articulated in any part thereof.

The draft policy, at the outset, should have general guiding principles of publishing data openly and freely (once it meets the utility test, and it has been ensured that individual privacy will not be violated by the publishing of such statistics). This should serve well to inform further regulations and related policies governing the use and publishing of statistics, like the Statistical Disclosure Control Report.

A general commitment to a well-articulated policy on data dissemination will ensure easy-to-follow principles for the various Ministries that will refer to the document. The additional principles that come with open data principles should also be described by the policy document: a commitment to publishing data in a machine-readable format, making it available in multiple data formats (.txt, .csv, etc.), and including its metadata.

Data storage and usage

In the absence of a regime for data protection, it is absolutely necessary that a national policy on statistics provide positive mandates for the encryption of all digitally-stored personal and sensitive information collected through surveys. Even though the current draft of the policy mentions the need to protect confidential information, it sets no mandatory requirements on the Government to ensure the security of such information, especially on digital platforms.

Additionally, all transmission of potentially sensitive information should be done with the digital signatures of the employee/Department/Ministry authorising said transmission. This will ensure the integrity and authenticity of the information, and provide with an auditable trail of the information flowing between entities in the various bodies.

Data privacy

It is appreciable that Section 5.7.9 of the draft policy notes, “[a]ll statistical surveys represent a degree of privacy invasion, which is justified by the need for an alternative public good, namely information.” However, all statistical surveys may not be proportionate in their invasiveness, even if they might serve a legitimate public goal in the future.

The draft policy does not address how privacy concerns can be taken into account while designing the survey itself. A necessary outcome of the realisation of the possible privacy violations that may arise due to surveys is that all data collection be “minimally intrusive”, the data be securely stored (see previous comment section, ‘Data storage and usage’), and the surveyed users have control over the data even after they have parted with their information.

Since the policy deals extensively with the implementation of surveys, the following should details should be clearly laid out in the policy:

- The extent to which an individual has control over the data they have provided to the surveying agency.

- The means of redressal available to an individual who feels that his/her privacy has been violated through the publication of certain statistical information

Specific Comments

Section 5.1: Dichotomising official statistics as core statistics and other official statistics

Comments

The reasons for dichotomising official statistics has not been appropriately substantiated with evidence, considering the wide implications of policy proposals that arise from the definition of “core statistics.”

Firstly, the descriptions of what constitutes “core statistics” casts too wide a net by only having a single vague qualitative criterion, i.e. “national importance.” All the other characteristics of the “core statistics” are either recommendations or requirements as to how the data will be handled and thus, pose no filter to what can constitute “core statistics.” The wide net is apparent in the fact that even the initially-proposed list of “core statistics”, given in Annex-II of the policy, has 120 categories of statistics.

Secondly, the policy does not provide reasons for why the characteristics of “core statistics”, highlighted in Section 5.1.5, should not apply to all official statistics at the various levels of Government. Therefore, the utility of the proposed dichotomy has also not been appropriately substantiated with illustrative examples of how “core statistics” should be considered qualitatively different from all official statistics.

This definition may lead to widespread disagreement between the States and the Centre, because Section 5.2 proposes that “core statistics” be added to the Union List of the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution. How the proposal may affect Centre-State responsibilities and relations pertaining to the collection and dissemination of statistics is elaborated in the next section.

Recommendations

The policy should not make a forced dichotomy between “core” and (ipso facto) non-core statistics. If a distinction is to be made for any reason(s) (such as for the purposes of delineating administrative roles) then such reason must be clearly defined, along with a clear explanation for why such a dichotomy would alleviate the described problem. The definitions should have tangible and unambiguous qualitative criteria.

Section 5.2: Constitutional amendment in respect of core statistics

Comments

The main proposal in the section is that the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution be amended to include “core statistics” in the Union List. This would give the Parliament the legislative competence to regulate the collection, storage, publication and sharing of such statistics, and the Central Government the power to enforce such legislation. Annex-II provides a tentative list of what would constitute “core statistics”; as is apparent, this list is wide-ranging and consists over 120 items which span the gamut of administrative responsibilities.

The list includes items such as “Landholdings Number, area, tenancy, land utilisation [...]” (S. No. 21), and “Statistics on land records” (S. No. 111) while most responsibilities of land regulation currently lie with the States. Similarly, items in Annex-II venture into statistics related to petroleum, water, agriculture, electricity, and industry; some of which are in the Concurrent or State List.

Statistics are metadata. There is no reason for why the administration of a particular subject lie with the State, and the regulation of data about such subject should lie with solely with the Central Government. It is important to recognise that adding the vaguely defined “core statistics” to the Union List, while enabling the Central Government to execute and plan such statistical exercises, will also prevent the States from enacting any legislation that regulates the management of statistics regarding its own administrative responsibilities.

The regulation of State Government records in general has been a contentious issue, and its place in our federal structure has been debated several times in the Parliament: the enactment of Public Records Act, 1993; the Right to Information Act, 2005; and the Collection of Statistics Act, 2008 are predicated on an assumption of such competence lying with the Parliament. However, it is equally important to recognise the role States have played in advancing transparency of Government records. For example, State-level Acts analogous to the Right to Information Act existed in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka before the Central Government enactment.

Recommendations

We strongly recommend that “statistics” be included in the Concurrent List, so that States are free to enact progressive legislation which advances transparency and accountability, and is not in derogation of Parliamentary legislation.

The Ministry should view this statistical policy document as a venue to set the minimum standards for the collection, handling and publication of statistics regarding its various functions. If the item is added to the Concurrent List, the States, through local legislation, will only have the power to improve on the Central standards since in a case of conflict, State-levels laws will be superseded by Parliamentary ones.

Section 5.3: Mechanism for regulating core statistics including auditing

Comments

The draft policy in Section 5.3.2 says, “[...] The Committee will be assisted by a Search Committee headed by the Vice-Chairperson of the NITI Aayog, in which a few technical experts could be included as Members.” The non-commital nature of the word ‘could’ in this statement detracts from the importance of having technical experts on this committee, by making their inclusion optional. The policy also does not specify who has the power to include technical experts as Members in the Search Committee. The statement should include either a minimum number of a specific number or members, and not use the non-committal word “could”

The National Statistical Development Council, as mentioned in 5.3.9, is supposed to “handle Centre-State relations in the areas of official statistics, the Council should be represented by Chief Ministers of six States to be nominated by the Centre” (Section 5.3.10). The draft does not elaborate on the rationale behind including just six states in the Council. It does not recommend any mechanism on the basis of which Centre will nominate states in the council.

Recommendations

The policy should recommend a minimum number of technical experts who must be included in the search committee, along with a clear process for how such members are to be appointed.

Additionally, the policy appropriately recognises the great diversity in India and the unique challenges faced by each State. Thus, each State has its unique requirements. Since in Section 5.3.11, the policy recommends that council meet at a low frequency of at least once in a year, all States should be represented in the Council.

Section 5.4: Official Machinery to implement directions on core statistics

Comments

The functions of Statistics Wing in the MOSPI, laid out in Section 5.4.7, include advisory functions which overlap with functions of National Statistical Commission (NSC) mentioned in Section 5.3.5. Some regulatory functions of Statistics Wing, like “conducting quality checks and auditing of statistical surveys/data sets”, overlap with the regulatory functions of NSC mentioned in Section 5.3.7.

In section 5.3.1, the draft policy explicitly mentions that “what is feasible and desirable is that production of official statistics should continue with the Government, whereas the related regulatory and advisory functions could be kept outside the Government”. But Statistics Wing is a part of the government and it also has regulatory and advisory functions. It will adversely affect the power of NSC as an autonomous body.

There are inconsistencies in the draft-policy regarding the importance and need of a decentralized statistical system. In section 3 [Objectives], it has been emphasized that the Indian Statistical System shall function within decentralized structure of the system. But, in section 5.4.15, the draft says that decentralized statistical system poses a variety of problems, and advocates for a unified statistical system. Again, in section 5.15, draft emphasizes the development of sub-national statistical systems. These views are inconsistent and create confusion regarding the nature of statistical system that policy wants to pursue.

Recommendations

The functions of the NSC should be kept in its exclusive domain. Any such overlapping functions should be allocated to one agency taking into consideration the Fundamental Principles on Official Statistics.

The inconsistencies regarding the decentralisation philosophy of the statistical system should be addressed.

Section 5.5: Identifying statistical products required through committees

Comments

While Section 5.5.2 recognises data confidentiality as a goal for statistical coordination, it does not take into account the violation of privacy that might occur due to the sharing of data. For example, a certain individual might agree to share personal information with a particular Ministry, but have apprehensions about it being shared with other Ministries or private parties.

Recommendations

We recommend that point 4 in Section 5.5.2 be read as, “enabling sharing of data without compromising the privacy of individuals and the confidentiality/security of data.”The value of of the individual privacy stems from both the recent Supreme Court judgment that affirmed privacy as a Fundamental Right, and also Principle 6 of the of the Fundamental Principles of Official Statistics. Realising privacy as a goal in this section will add a realm of individual control that is already articulated in Section 5.7.9.

Annex-VII: Guidelines on Outsourcing statistical activities

Comments

Section 6 defines “sensitive information” in an all-inclusive manner and does not leave space for further inclusion of any information that may be interpreted as sensitive. For example, biometric data has not been listed as “sensitive information”.

Section 9.1, draft says, “[t]he identity of the Government agency and the Contractor may be made available to informants at the time of collection of data”. It is imperative that informants have the right to verify the identity of the Government agency and the Contractor before parting with their personal information.

Recommendations

The definition of “sensitive information” should be broad-based with scope for further inclusion of any kind of data that may be deemed “sensitive.”

Section 9.1 must mandate that the identity of the Government agency and the Contractor be made available to informants at the time of collection of data.

Section 9.6 can be redrafted to state that each informant must be informed of the manner in which the informant could access the data collected from the informant in a statistical project, as also of the measures taken to deny access on that information to others, except in the cases specified by the policy.

Section 10.2 can be improved to state that if information exists in a physical form that makes the removal of the identity of informants impracticable (e.g. on paper), the information should be recorded in another medium and the original records must be destroyed.

Network Disruptions Report by Global Network Initiative

The report by Global Network Initiative can be read here.

However S.144 of the Criminal Procedure Code as well Section 5 of the Telegraph Act are still used as legal grounds. The former targets unlawful assembly while the latter gives authorities the right to prevent transmission of messages, applicable to messages sent over the Internet as well. A case in the Gujarat High Court challenging the validity of using S.144 of the CrPC was dismissed essentially stating the Government could use the section to enforce shutdowns to maintain law and order.

The right to Internet has been accepted as a fundamental right by the United Nations and one which, cannot be disassociated from the exercise of freedom of expression and opinion and the right to peaceful assembly. These are rights guaranteed by the Constitution, affirmed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and thus should be provided, both, online and offline. Online movements are unpredictable and dynamic making Governments fearful of their lack of control over content hosting websites. Their fear becomes their de facto perception of online services resulting in network shutdowns regardless of the reality on ground.

Given the rising importance of this issue, Global Network Initiative has published a report on such Network Disruptions by Jan Rydzak . A former Google Policy fellow and now a PhD candidate at the University of Arizona, he, conducts research on the nexus between technology and protest. The report, which uses India as a case study calls for more attention on network disruptions, the 'new form of digital repression' and delves into its impact on human rights. Rydzak aims at widening the gambit of affected rights by discussing the civil and political rights of freedom of assembly, right to equality, religious belief and such. These are ramifications not widely discussed so far and helps shine a light on the collateral damage incurred due to these shutdowns. Through a multitude of interviews with various stakeholders, the author brings to forefront the human rights implications of network disruptions on different groups of individuals such as women, immigrants and certain ethnic groups. These dangers are even more when it comes to vulnerable populations and the report does a comprehensive analysis of all of the above.

NITI Aayog Discussion Paper: An aspirational step towards India’s AI policy

The 115-page discussion paper attempts to be an all encompassing document looking at a host of AI related issues including privacy, security, ethics, fairness, transparency and accountability. The paper identifies five focus areas where AI could have a positive impact in India. It also focuses on reskilling as a response to the potential problem of job loss due the future large-scale adoption of AI in the job market. This blog is a follow up to the comments made by CIS on Twitter on the paper and seeks to reflect on the National Strategy as a well researched AI roadmap for India. In doing so, it identifies areas that can be strengthened and built upon.

Identified Focus Areas for AI Intervention

The paper identifies five focus areas—Healthcare, Agriculture, Education, Smart Cities and Infrastructure, Smart Mobility and Transportation, which Niti Aayog believes will benefit most from the use of AI in bringing about social welfare for the people of India. Although these sectors are essential in the development of a nation, the failure to include manufacturing and services sectors is an oversight. Focussing on manufacturing is fundamental not only in terms of economic development and user base, but also regarding questions of safety and the impact of AI on jobs and economic security. The same holds true for the service sector particularly since AI products are being made for the use of consumers, not just businesses. Use of AI in the services sector also raises critical questions about user privacy and ethics. Another sector the paper fails to include is defense, this is worrying since India is chairing the Group of Governmental Experts on Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems (LAWS) in 2018. Across sectors, the report fails to look at how AI could be utilised to ensure accessibility and inclusion for the disabled. This is surprising, as aid for the differently abled and accessibility technology was one of the 10 domains identified in the Task Force Report on AI published earlier this year. This should have been a focus point in the paper as it aims to identify applications with maximum social impact and inclusion.

In its vision for the use of AI in smart cities, the paper suggests the adoption of a sophisticated surveillance system as well as the use of social media intelligence platforms to check and monitor people’s movement both online and offline to maintain public safety. This is at variance with constitutional standards of due process and criminal law principles of reasonable ground and reasonable suspicion. Further, use of such methods will pose issues of judicial inscrutability. From a rights perspective, state surveillance can directly interfere with fundamental rights including privacy, freedom of expression, and freedom of assembly. Privacy organizations around the world have raised concerns regarding the increased public surveillance through the use of AI. Though the paper recognized the impact on privacy that such uses would have, it failed to set a strong and forward looking position on the issue - such as advocating that such surveillance must be lawful and inline with international human rights norms.

Harnessing the Power of AI and Accelerating Research

One of the ways suggested for the proliferation of AI in India was to increase research, both core and applied, to bring about innovation that can be commercialised. In order to attain this goal the paper proposes a two-tier integrated approach: the establishment of COREs (Centres of Research Excellence in Artificial Intelligence) and ICTAI (International Centre for Transformational Artificial Intelligence). However the roadmap to increase research in AI fails to acknowledge the principles of public funded research such as free and open source software (FOSS), open standards and open data. The report also blames the current Indian Intellectual Property regime for being “unattractive” and averse to incentivising research and adoption of AI. Section 3(k) of Patents Act exempts algorithms from being patented, and the Computer Related Inventions (CRI) Guidelines have faced much controversy over the patentability of mere software without a novel hardware component. The paper provides no concrete answers to the question of whether it should be permissible to patent algorithms, and if yes, to to what extent. Furthermore, there needs to be a standard either in the CRI Guidelines or the Patent Act, that distinguishes between AI algorithms and non-AI algorithms. Additionally, given that there is no historical precedence on the requirement of patent rights to incentivise creation of AI, innovative investment protection mechanisms that have lesser negative externalities, such as compensatory liability regimes would be more desirable. The report further failed to look at the issue holistically and recognize that facilitating rampant patenting can form a barrier to smaller companies from using or developing AI. This is important to be cognizant of given the central role of startups to the AI ecosystem in India and because it can work against the larger goal of inclusion articulated by the report.

Ethics, Privacy, Security and Safety

In a positive step forward, the paper addresses a broader range of ethical issues concerning AI including transparency, fairness, privacy and security and safety in more detail when compared to the earlier report of the Task Force. Yet despite a dedicated section covering these issues, a number of concerns still remain unanswered.

Transparency

The section on transparency and opening the Black Box has several lacunae. First, AI that is used by the government, to an acceptable extent, must be available in the public domain for audit, if not under Free and Open Source Software (FOSS). This should hold true in particular for uses that impinge on fundamental rights. Second, if the AI is utilised in the private sector, there currently exists a right to reverse engineer within the Indian Copyright Act, which is not accounted for in the paper. Furthermore, if the AI was involved both in the commission of a crime or the violation of human rights, or in the investigations of such transgressions, questions with regard to judicial scrutability of the AI remain. In addition to explainability, the source code must be made circumstantially available, since explainable AI alone cannot solve all the problems of transparency. In addition to availability of source code and explainability, a greater discussion is needed about the tradeoff between a complex and potentially more accurate AI system (with more layers and nodes) vs. an AI system which is potentially not as accurate but is able to provide a human readable explanation. It is interesting to note that transparency within human-AI interaction is absent in the paper. Key questions on transparency, such as whether an AI should disclose its identity to a human have not been answered.

Fairness

With regards to fairness, the paper mentions how AI can amplify bias in data and create unfair outcomes. However, the paper neither suggests detailed or satisfactory solutions nor does it deal with biased historical data in an Indian context. More specifically, there seems to be no mention of regulatory tools to tackle the problem of fairness, such as:

- Self-certification

- Certification by a self-regulatory body

- Discrimination impact assessments

- Investigations by the privacy regulator

Such tools will proactively need to ensure inclusion, diversity, and equity in composition and decisions.

Additionally, with reference to correcting bias in AI, it should be noted that the technocratic view that as an AI solution continues to be trained on larger amounts of data , systems will self correct, does not fully recognize the importance of data quality and data curation, and is inconsistent with fundamental rights. Policy objectives of AI innovation must be technologically nuanced and cannot be at the cost of intermediary denial of rights and services.

Further, the paper does not deal with issues of multiple definitions and principles of fairness, and that building definitions into AI systems may often involve choosing one definition over the other. For instance, it can be argued that the set of AI ethical principles articulated by Google are more consequentialist in nature involving a a cost-benefit analysis, whereas a human rights approach may be more deontological in nature. In this regard, there is a need for interdisciplinary research involving computer scientists, statisticians, ethicists and lawyers.

Privacy

Though the paper underscores the importance of privacy and the need for a privacy legislation in India - the paper limits the potential privacy concerns arising from AI to collection, inappropriate use of data, personal discrimination, unfair gain from insights derived from consumer data (the solution being to explain to consumers about the value they as consumers gain from this), and unfair competitive advantage by collecting mass amounts of data (which is not directly related to privacy). In this way the paper fails to discuss the full implications on privacy that AI might have and fails to address the data rights necessary to enable the right to privacy in a society where AI is pervasive. The paper fails to engage with emerging principles from data protection such as right to explanation and right to opt-out of automated processing, which directly relate to AI. Further, there is no discussion on the issues such as data minimisation and purpose limitation which some big data and AI proponents argue against. To that extent, there is a lack of appreciation of the difficult policy questions concerning privacy and AI. The paper is also completely silent on redress and remedy. Further the paper endorses the seven data protection principles postulated by the Justice Srikrishna Committee. However CIS has pointed out that these principles are generic and not specific to data protection. Moreover, the law chapter of IEEE’s ‘Global Initiative on Ethics of Autonomous and Intelligent Systems’ has been ignored in favor of the chapter on ‘Personal Data and Individual Access Control in Ethically Aligned Design’ as the recommended international standard. Ideally, both chapters should be recommended for a holistic approach to the issue of ethics and privacy with respect to AI.

AI Regulation and Sectoral Standards

The discussion paper’s approach towards sectoral regulation advocates collaboration with industry to formulate regulatory frameworks for each sector. However, the paper is silent on the possibility of reviewing existing sectoral regulation to understand if they require amending. We believe that this is an important solution to consider since amending existing regulation and standards often takes less time than formulating and implementing new regulatory frameworks. Furthermore, although the emphasis on awareness in the paper is welcome, it must complement regulation and be driven by all stakeholders, especially given India’s limited regulatory budget. The over reliance on industry self-regulation, by itself, is not advisable, as there is an absence of robust industry governance bodies in India and self-regulation raises questions about the strength and enforceability of such practices. The privacy debate in India has recognized this and reports, like the Report of the Group of Experts on Privacy, recommend a co-regulatory framework with industry developing binding standards that are inline with the national privacy law and that are approved and enforced by the Privacy Commissioner. That said, the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and its “protect, respect, and remedy” framework should guide any self regulatory action.

Security and Safety of AI Systems

In terms of security and safety of AI systems the paper seeks to shift the discussion of accountability being primarily about liability, to that of one about the explainability of AI. Furthermore, there is no recommendation of immunities or incentives for whistleblowers or researchers to report on privacy breaches and vulnerabilities. The report also does not recognize certain uses of AI as being more critical than others because of their potential harm to the human. This would include uses in healthcare and autonomous transportation. A key component of accountability in these sectors will be the evolution of appropriate testing and quality assurance standards. Only then, should safe harbours be discussed as an extension of the negligence test for damages caused by AI software. Additionally, the paper fails to recommend kill switches, which should be mandatory for all kinetic AI systems. Finally, there is no mention of mandatory human-in-the-loop in all systems where there are significant risks to safety and human rights. Autonomous AI is only viewed as an economic boost, but its potential risks have not been explored sufficiently. A welcome recommendation would be for all autonomous AI to go through human rights impact assessments.

Research and Education

Being a government think-tank, the NITI Aayog could have dealt in detail with the AI policies of the government and looked at how different arms of the government are aiming to leverage AI and tackle the problems arising out of the use of AI. Instead of tabulating the government’s role in each area and especially research, the report could have also listed out the various areas where each department could play a role in the AI ecosystem through regulation, education, funding research etc. In terms of the recommendations for introducing AI curriculums in schools, and colleges, the government could also ensure that ethics and rights are part of the curriculum - especially in technical institutions. A possible course of action could include corporations paying for a pan-Indian AI education campaign.This would also require the government to formulate the required academic curriculum that is updated to include rights and ethics.

Data Standards and Data Sharing

Based on the amount of data the Government of India collects through its numerous schemes, it has the potential to be the largest aggregator of data specific to India. However the paper does not consider the use of this data with enough gravity. For example, the paper recommends Corporate Data Sharing for “social good” and making government datasets from the social sector available publicly. Yet this section does not mention privacy enhancing technologies/standards such as pseudonymization, anonymization standards, differential privacy etc. Additionally there should be provisions that allow the government to prevent the formation of monopolies by regulating companies from hoarding user data. The open data standards could also be applicable to the private companies, so that they can also share their data in compliance with the privacy enhancing technologies mentioned above. The paper also acknowledges that AI Marketplaces require monitoring and maintenance of quality. It recognises the need for “continuous scrutiny of products, sellers and buyers”, and proposes that the government enable these regulations in a manner that private players could set up the marketplace. This is a welcome suggestion, but the legal and ethical framework of the AI Marketplace requires further discussion and clarification.

An AI Garage for Emerging Economies

The discussion paper also qualifies India as an “ideal test-bed” for trying out AI related solutions. This is problematic since questions of regulation in India with respect to AI have yet to be legally clarified and defined and India does not have a comprehensive privacy law. Without a strong ethical and regulatory framework, the use of new and possibly untested technologies in India could lead to unintended and possibly harmful outcomes.The government's ambition to position India as a leader amongst developing countries on AI related issues should not be achieved by using Indians as test subjects for technologies whose effects are unknown.

Conclusion

In conclusion, NITI Aayog’s discussion paper represents a welcome step towards a comprehensive AI strategy for India. However, the trend of inconspicuously releasing reports (this and the AI Task Force) as well as the lack of a call for public comments, seems to be the wrong way to foster discussion on emerging technologies that will be as pervasive as AI.

The blanket recommendations were provided without looking at its viability in each sector. Furthermore, the discussion paper does not sufficiently explore or, at times, completely omits key areas. It barely touched upon societal, cultural and sectoral challenges to the adoption of AI — research that CIS is currently in the process of undertaking.Future reports on Indian AI strategy should pay more attention to the country’s unique legal context and to possible defense applications and take the opportunity to establish a forward looking, human rights respecting, and holistic position in global discourse and developments. Reports should also consider infrastructure investment as an important prerequisite for AI development and deployment. Digitised data and connectivity as well as more basic infrastructure, such as rural electricity and well-maintained roads, require more funding to more successfully leverage AI for inclusive economic growth. Although there are important concerns, the discussion paper is an aspirational step toward India’s AI strategy.

Why NPCI and Facebook need urgent regulatory attention

The article was published in the Economic Times on June 10, 2018.

As the network effects compound, disruptive acceleration hurtle us towards financial utopia, or dystopia. Our fate depends on what we get right and what we get wrong with the law, code and architecture, and the market.

The Internet, unfortunately, has completely transformed from how it was first architected. From a federated, generative network based on free software and open standards, into a centralised, environment with an increasing dependency on proprietary technologies.

In countries like Myanmar, some citizens misconstrue a single social media website, Facebook, for the internet, according to LirneAsia research. India is another market where Facebook could still get its brand mistaken for access itself by some users coming online. This is Facebook put so many resources into the battle over Basics, in the run-up to India’s network neutrality regulation. an odd corporation.

On hand, its business model is what some term surveillance capitalism. On the other hand, by acquiring WhatsApp and by keeping end-toend (E2E) encryption “on”, it has ensured that one and a half billion users can concretely exercise their right to privacy. At the time of the acquisition, WhatsApp founders believed Facebook’s promise that it would never compromise on their high standards of privacy and security. But 18 months later, Facebook started harvesting data and diluting E2E.

In April this year, my colleague Ayush Rathi and I wrote in Asia Times that WhatsApp no longer deletes multimedia on download but continues to store it on its servers. Theoretically, using the very same mechanism, Facebook could also be retaining encrypted text messages and comprehensive metadata from WhatsApp users indefinitely without making this obvious.

My friend, Srikanth Lakshmanan, founder of the CashlessConsumer collective, is a keen observer of this space. He says in India, “we are seeing an increasing push towards a bank-led model, thanks to National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) and its control over Unified Payments Interface (UPI), which is also known as the cashless layer of the India Stack.”

NPCI is best understood as a shape shifter. Arundhati Ramanathan puts it best when she says “depending on the time and context, NPCI is a competitor. It is a platform. It is a regulator. It is an industry association. It is a profitable non-profit. It is a rule maker. It is a judge. It is a bystander.”

This results in UPI becoming, what Lakshmanan calls, a NPCI-club-good rather than a new generation digital public good. He also points out that NPCI has an additional challenge of opacity — “it doesn’t provide any metrics on transaction failures, and being a private body, is not subject to proactive or reactive disclosure requirements under the RTI.”

Technically, he says, UPI increases fragility in our financial ecosystem since it “is a centralised data maximisation network where NPCI will always have the superset of data.” Given that NPCI has opted for a bank-led model in India, it is very unlikely that Facebook able to leverage its monopoly the social media market duopoly it shares with in the digital advertising market to become a digital payments monopoly.

However, NCPI and Facebook both share the following traits — one, an insatiable appetite for personal information; two, a fetish for hypercentralisation; three, a marginal commitment to transparency, and four, poor track record as a custodian of consumer trust. The marriage between these like-minded entities has already had a dubious beginning.

Previously, every financial technology wanting direct access to the NPCI infrastructure had to have a tie-up with a bank. But for Facebook and Google, as they are large players, it was decided to introduce a multi-bank model. This was definitely the right thing to do from a competition perspective. But, unfortunately, the marriage between the banks and the internet giant was arranged by NPCI in an opaque process and WhatsApp was exempted from the full NPCI certification process for its beta launch.

Both NPCI and Facebook need urgent regulatory attention. A modern data protection law and a more proactive competition regulator is required for Facebook. The NPCI will hopefully also be subjected to the upcoming data protection law. But it also requires a range of design, policy and governance fixes to ensure greater privacy and security via data minimisation and decentralisation; greater accountability and transparency to the public; separation of powers for better governance and open access policies to prevent anti-competitive behaviour.

Comments on the Draft Digital Communications Policy

Preliminary

On 1st May 2018, the Department of Telecommunications of the Ministry of Communications released the Draft Digital Communications Policy for comments and feedback. We laud the Government’s attempts to realise the socio-economic potential of India by increasing access to Internet, and drafting a comprehensive policy while adequately keeping in mind the various security and privacy concerns that arise due to online communication. On behalf of the Centre for Internet & Society (CIS), we thank the Department of Telecommunications for the opportunity to submit its comments on the draft policy.

We would like to point out two concerns with the consultation process: (i) a character-limit imposed on the comments to each section, due to which this submission has to sacrifice on providing comprehensive references to research; and (ii) issues with signing in on the MyGov where this consultation was hosted. We strongly recommend that the consultation process be liberal in accepting content, and allow for multiple types of submissions.

Comments

Connect India: Creating a Robust Digital Communication Infrastructure

Propel India: Enabling Next Generation Technologies and Services through Investments, Innovation, Indigenous Manufacturing and IPR Generation

On Strategies

2.2 (a) ii. Simplifying licensing and regulatory frameworks whilst ensuring appropriate security frameworks for IoT/ M2M / future services and network elements incorporating international best practices

The process of “simplifying” licensing and regulatory regime is currently vague, and the intentions remain unclear. Simplifying licences without clear intentions can lead to losing the necessary nuance in the license agreements required to maintain competitive markets. In recent months, the industry has already witnessed a dilution of provisions which were placed to ensure healthy competition in the sector. For example, on May 31st, new norms were announced by DoT under which now allow an operator to hold 35% of the total spectrum as opposed to the earlier regulation which only allowed for holding a maximum 25% of the total spectrum.

2.3 (d) (iii) Providing financial incentives for the development of Standard Essential Patents(SEPs) in the field of digital communications technologies

This is a welcome step by the government to incentivise the development of SEPs in the country. However, this appreciable step will only yield results in the long term - and realistically speaking, not before a decade. It is equally necessary to improve the environment of licensing of SEPs in the short-term. The government should take initiative for creation of government-controlled patent pools for SEPs, which will solve issues of licensing for SEP holders, and also improve transparency of information relating to SEPs. Specifically, we recommend that the government initiate the formation of a patent pool of critical mobile technologies and apply a five percent compulsory license.

Secure India: Ensuring Digital Sovereignty, Safety and Security of Digital Communications

On Strategies

3.1 Harmonising communications law and policy with the evolving legal framework and jurisprudence relating to privacy and data protection in India

We welcome the Ministry’s intention to amend licence agreements to include data protection and privacy provisions. In the same vein, the Ministry should also consider removing provisions from licenses that prevent the operator from using certain encryption methods in its network. For example, Clause 2.2 (vii) of the License Agreement between DoT & ISP prohibits bulk encryption. Additionally, in the License Agreement, encryption with only up to 40-bit in RSA (or equivalent) is normally permitted. Similarly, Clause 37.1 of the Unified Service License Agreement prohibits bulk encryption. These provisions must be revised to ensure that ISPs and other service providers can employ more cryptographically secure methods.

When regulating on encryption, we recommend that the government only set positive minimum mandates for the storage and transmission of data, and not set upper limits on the number of bits or on the quality of cryptographical method. In pursuance of the same goals, we also recommend adding point ‘iii’ to 3.1 (b): “promoting the use of encryption in private communication by providing positive minimum mandates for strong encryption in (or along with) the data protection framework.”

3.2 (a) Recognising the need to uphold the core principles of net neutrality