Blog

An Introduction to Bitfilm & Bitcoin in Bangalore, India

See the blog post published in Benson's Blog

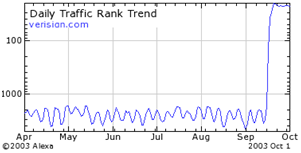

Aaron Koenig gave a talk on the creation and use of Bitcoin, and on a payment system designed for the voting process of the Bitfilm Festival for Digital Film. Since the year 2000, the Bitfilm Festival has been showcasing films that use digital technology in a creative and innovative way. It takes place on the Internet. However, physical screenings of the films will be held in Bangalore and in Hamburg. Each of the 59 nominated digital animations has its own Bitcoin account, and users worldwide may vote by donating Bitcoins to the films they like anonymously and without any transfer costs. The donated money will be divided among the most popular films (the films with the most votes/Bitcoins).

A strong knowledgeable speaker, Aaron brought forward his tremendous knowledge of Bitcoin, Art & Economics.

The Twitter based Q&A can be viewed on the Twitter ID's of

@pranesh_prakash

@cis_india

@bensonsamuel

The Newspaper Articles where Bitfilm & Bitcoin made their news in India were

Deccan Herald - http://bit.ly/U74YsS

The Hindu - http://goo.gl/YJYni

The Bangalore Mirror - http://bit.ly/XfDRbZ

Bitcoin Resources In India

Local Exchange - LocalBitcoins.com

India Fourms - https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?board=89.0

Blogs - bensonsamuel.com

Services - indiabitcoin.com - Official Partners of Bitpay USA in India

Meetup Group - http://www.meetup.com/Bitcoin-Bangalore-Meetup-Group/

Video

Draft Human DNA Profiling Bill (April 2012): High Level Concerns

This research was undertaken as part of the 'SAFEGUARDS' project that CIS is undertaking with Privacy International and IDRC.

Each database will contain profiles of victims, offenders, suspects, missing persons and volunteers for the purpose of establishing identity in criminal and civil proceedings. The Bill also establishes a process for certifying DNA laboratories, and creating a DNA board for overseeing the carrying out of the Act. Though it is important to carefully regulate the use of DNA for criminal purposes, and such a law is needed in India, the present working draft of the Bill is lacking important safeguards and contains overreaching provisions, which could lead to violation of individual rights. The text of the 2012 draft is still being discussed and has not been finalized. Below are high level concerns that CIS has with the April 2012 draft Human DNA Profiling Bill.

Broad offences and instances of when DNA can be collected

The schedule of the Bill lists applicable instances for human DNA profiling and addition to the DNA database. Under this list, the Bill lays out nine Acts, for example the Indian Penal Code and the Protection of Civil Rights Act, and states that offences under these Acts are applicable instances of human DNA profiling. This allows the scope of the database to be expansive, as any individual who has committed an offence found under any of these Acts to be placed on the DNA database, and might include offences for which DNA evidence is not useful.

In the schedule under section C Civil disputes and other civil matters the Bill lists a number of civil disputes and civil matters for which DNA can be taken and entered onto the database. For example:

- (v) Issues relating to immigration or emigration

- (vi) Issues relating to establishment of individual identity

- (vii) Any other civil matter as may be specified by the regulations of the Board

In these instances no crime has been committed and there is no justification for taking the DNA of the individual without their consent. In cases of civil disputes

Recommendation: Offences for which DNA can be collected must be criminal and must be specified individually by the Bill. When DNA is used in civil cases, the consent of the individual must be taken. In civil cases a DNA profile should not be stored on the database. DNA profiling and storage on a database should not be allowed in instances like v, vi, vii listed above.

Inadequate level of authorization for sharing of information

The Bill allows for the DNA Data Bank Manager to determine when it is appropriate to communicate whether the DNA profile received is already contained in the Data Bank, and any other information contained in the Data Bank in relation to the DNA profile received.

- Section 35 (1): “…shall communicate, for the purposes of the investigation or prosecution in a criminal offence, the following information to a court, tribunal, law enforcement agency, or DNA laboratory in India which the DNA Data Bank Manager considers is concerned with it, appropriate, namely (a) as to whether the DNA profile received is already contained in the Data Bank; and (b) any information, other than the DNA profile received, is contained in the Data Bank in relation to the DNA profile received.”

Recommendation: The Data Bank Manager should not be given the power to determine appropriate instances for the communication of information. Law enforcement agencies, DNA laboratories, etc. should be required to gain prior authorization, from the DNA Board, before requesting the disclosure of information from the DNA Data Bank Manager. Upon receiving proof of authorization, the DNA databank can share the requested information.

Inaccurate understanding of infallibility of DNA

The preamble to the Bill inaccurately states:

The Dexoxyribose Nucleic Acid (DNA) analysis of body substances is a powerful technology that makes it possible to determine whether the source of origin of one body substance is identical to that of another, and further to establish the biological relationship, if any between two individuals, living or dead without any doubt.

Recommendation: The Bill should recognize that DNA evidence is not infallible. For example, false matches can occur based on the type of profiling system used, and that error can take place in the chain of custody of the DNA sample.

The “definition” of DNA profiling is too loose in the Bill. Any technology used to create DNA profiles is subject to error. The estimate of this error should be experimentally obtained, rather than being a theoretical projection.

Inadequate access controls

The Bill only restricts access to information on the DNA database that relates to a victim or to a person who has been excluded as a suspect in relevant investigations.

Section 43: Access to the information in the National DNA Data Bank shall be restricted in the manner as may be prescribed if the information relates to a DNA profile derived from a) a victim of an offence which forms or formed the object of the relevant investigation, or b) a person who has been excluded as a suspect in the relevant investigation.

Recommendation: Though it is important that access is restricted in these instances, access should also be restricted for: volunteers, missing persons, and victims. Broad access to every index in the database should not be permitted when a DNA sample for a crime is being searched for a match. Ideally, a crime scene index will be created, and samples will only be compared to that specific crime scene. The access procedure should be transparent with regular information published in an annual report, minutes of oversight meetings taken, etc.

Lack of standards and process for collection of DNA samples

In three places the Bill mentions that a procedure for the collection of DNA profiles will be established, yet no process is enumerated in the actual text of the Bill.

- Section 12 (w) “The Board will have the power to… specify by regulation, the list of applicable instances of human DNA profiling and the sources and manner of collection of samples in addition to the lists contained in the Schedule.

- Section 66(d) “The Central Government will have the power to make Rules pertaining to… The list of applicable instances of human DNA profiling and the sources and manner of collection of samples in addition to the lists contained in the Schedule under clause (w) of section 12.

- Schedule: In the title “List of applicable instances of Human DNA Profiling and Sources and Manner of Collection of Samples for DNA Profiling”. But the schedule does not detail the manner of collection of samples for DNA profiling.

Recommendation: According to the Criminal Procedure Code, section 53 and 54, DNA samples can only be collected by certified medical professionals. This must be reflected by the Bill. The Bill should also state that the collection of DNA must take place in a secure location and in a secure manner. When DNA is collected, consent must be taken, unless the individual is convicted of a crime for which DNA evidence is directly relevant or the court has ordered the collection. When DNA is collected, personal identification information should not be sent with samples to laboratories, and all transfers of data (from police station to lab) must be secure. Upon collection, information regarding the collection of information and potential use and misuse of DNA information must be provided to the individual.

Inadequate appeal process

The provisions in the Bill allow aggrieved individuals to bring complaints to the DNA Board. If the complaint is not addressed, the individual can take the complaint to the court. Though grievances can be taken to the Board and the court, it is not clear if the individual has the right to appeal the collection, analysis, sharing, and use of his/her DNA. The text of section 58 implies that the Board and the Central government will have the power to take action based on complaints. This power was not listed above in the sections where the powers of the board and the central government are defined, thus it is unclear what actions the Board or the Central Government would be able to take on complaint.

Section 58: No court shall take cognizance of any offence punishable under this Act or any rules or regulations made thereunder save on a complaint made by the Central Government or its officer or Board or its officer or any other person authorized by them: Provided that nothing contained in this sub-section shall prevent an aggrieved person from approaching a court, if upon his application to the Central Government or the Board, no action is taken by them within a period of three months from the date of receipt of the application.

Recommendation: Individuals should be allowed to appeal a decision to collect DNA or share a DNA profile, and take any grievance directly to the court. If the Board or the Central Government will have a role in hearing complaints, etc. These must be enumerated in the provisions of the Act.

Inclusion of population testing

Though the main focus of the Bill is for the use of DNA in criminal and civil cases, the provisions of the Bill also allow for population testing and research to be done on collected samples.

Section 4: The Board shall consist of the following Members appointed from amongst persons of ability, integrity, and standing who have knowledge or experience in DNA profiling including.. (m) A population geneticist to be nominated by the President, Indian National Science Academy, Den Delhi-Member.

Section 40: Information relating to DNA profiles, DNA samples and records relating thereto shall be made available in the following instances, namely, (e) for creation and maintenance of a population statistics database that is to be used, as prescribed, or the purposes of identification research, protocol development or quality control provide that it does not contain any personally identifiable information and does not violate ethical norms.

Recommendation: Delete these provisions. If DNA testing is going to done for population analysis purposes, regulations for this must be provided for in a separate legislation, stored in separate database, informed consent taken from each participant, and an ethics board must be established. It is not sufficient or ethical to conduct population testing only on DNA samples from victims, offenders, suspects, and volunteers.

Provisions delegated to regulation that need to be incorporated into text of Bill

The Bill empowers the board to formulate regulations for, and the Central Government to make Rules to, a number of provisions that should be within the text of the Bill itself. By leaving these provisions to Regulations and Rules, the Bill is a skeleton which when enacted will only allow for DNA Labs to be certified and DNA databases to be established. Aspects that need to be included as provisions include:

Section 12: The Board shall exercise and discharge the following functions for the purposes of this Act namely

- Section 12(j) – authorizing procedures for communication of DNA profile for civil proceedings and for crime investigation by law enforcement and other agencies.

- Section 12(p) – making specific recommendations to (ii) ensure the accuracy, security, and confidentiality of DNA information, (iii) ensure the timely removal and destruction of obsolete, expunged or inaccurate DNA information (iv) take any other necessary steps required to be taken to protect privacy.

- Section 12(w) – Specifying, by regulation, the list of applicable instances of human DNA profiling and the sources a manner of collection of samples in addition to the lists contained in the Schedule.

- Section 12(u) – establishing procedure for cooperation in criminal investigation between various investigation agencies within the country and with international agencies.

- Section 12(x) – Enumerating the guidelines for storage of biological substances and their destruction.

Section 65(1) The Central Government may, by notification, make rules for carrying out the purposes of this Act

- Section 65 (c) – The officials who are authorized to receive the communication pertaining to information as to whether a person’s DNA profile is contained in the offenders’ index under sub-section (2) of section 35

- Section 65 (d) – The manner in which the DNA profile of a person from the offenders’ index shall be expunged under sub-section (2) of section 37

- Section 65 (e) – The manner in which the DNA profile of a person from the offender’s index shall be expunged under sub-section (3) of section 37

- Section 65 (h) – The manner in which access to the information in the DNA data Bank shall be restricted under section 43

- Section 65 (zg) – Authorization of other persons, if any, for collection of non-intimate forensic procedures under Part II of the Schedule.

Broad Language that needs to be specified or deleted

There are a number of places in the Bill which use broad and vague language. This is problematic as it expands the potential scope of the Bill. Instances where broad language is used includes:

Preamble: There is, thus, need to regulate the use of human DNA Profiles through an Act passed by the Parliament only for Lawful purposes of establishing identity in a criminal or civil proceeding and for other specified purposes.

- Section 12: The Board may make regulations for (j) authorizing procedures for communications of DNA profile for civil proceedings and for crime investigation by law enforcement and other agencies.

- Section 12: The Board may make regulations for (y) undertaking any other activity which in the opinion of the Board advances the purposes of this Act.

- Section 12: The Board may make regulations for (z) performing such other functions as may be assigned to it by the Central Government from time to time.

- Section 32: The indices maintained under sub-section (4) shall include information of data based on DNA analysis prepared by a DNA laboratory duly approved by the Board under section 15 of the Act and of records relating thereto, in accordance with the standards as may be specified by the regulations made by the Board.

- Section 35 (1) On receipt of a DNA profile for entry in the DNA Data Bank, the DNA Data Bank Manager shall cause it to be compared with the DNA profiles in the DNA Data Bank and shall communication, for purposes of the investigation or prosecution in a criminal offence, the following information…(a) as to whether the DNA profile received is already contained in the Data Bank and (b) any information other than the DNA profile received, is contained in the Data Bank in relation to the DNA profile received. (2) The information as to whether a person’s DNA profile is contained in the offenders’ index may be communicated to an official who is authorized to receive the same as prescribed.

- Section 39: All DNA profiles and DNA samples and records thereof shall be used solely for the purpose of facilitating identification of the perpetrator of a specified offence under Part I of the Schedule. Provided that such profiles or samples may be used to identify victims of accidents or disasters or missing persons or for purposes related to civil disputes and other civil matters listed in Part 1 of the Schedule for other purposes as may be specified by the regulations made by the board.

- Section 40: Information relating to DNA profiles, DNA samples and records relating thereto shall be made available in the following instances, namely (g) for any other purposes, as may be prescribed.

- Schedule, C Civil disputes and other civil matters vii) any other civil matter as may be specified y the regulations made by the Board.

Recommendation: All broad and vague language should be deleted and replaced with specific language.

Jurisdiction

- Section 1(2) It extends to the whole of India.

- Section 2(f) “Crime scene index” means an index of DNA profiles derived from forensic material found (i) at any place (whether within or outside of India) where a specified offence was, or is reasonably suspected of having been, committed.

The validity of DNA profiles found outside of India is unclear as the Act only extends to the whole of India.

Inconsistent provisions

The Bill contains provisions that are inconsistent including:

- Preamble … from collection to reporting and also to establish a National DNA Data Bank and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.

- Section 32 (1) The Central Government shall, by notification establish a National DNA Data Bank and as many Regional DNA Data Banks there under for every State or a group of States, as necessary. (2) Every State Government may, by notification establish a State DNA Data Bank which shall share the information with the National DNA Data Bank. The National DNA Data Bank shall receive DNA data from State DNA Data Banks…

Recommendation: The introduction to the Bill states that only a National DNA Data Bank will be established, yet in the provisions of the Bill it states that Regional and State level DNA databanks will also be established. It should be clarified in the introduction to the Bill that state level, regional level, and a national level DNA database will be created.

Inadequate qualifications of DNA Data Bank Manager

Section 33: “The DNA Data Bank Manager shall be a person not below the rank of Joint Secretary to the Government of India or equivalent and he shall report to the Member –Secretary of the Board. The DNA Data Bank Manager shall be a scientist with understanding of computer applications and statistics.”

Recommendation: This is not sufficient qualifications. The DNA Data Bank Manager needs to have experience and expertise handling, working with, and managing DNA for forensic purposes.

Lack of restrictions on labs seeking certification

According to section 16(2), before withdrawing approval granted to a DNA laboratory...the Board will give time to the laboratory...for taking necessary steps to comply with such directions...and conditions.”

Recommendation: This section should specify that during the time period of gaining certification, the DNA laboratory is not allowed to process DNA.

Incomplete terms for use of DNA in courts

Section 45 of the Bill allows any individual undergoing a sentence of imprisonment or under sentence of death to apply to the court which convicted him for an order for DNA testing. The Bill lists seven conditions that must be met for this DNA evidence to be accepted and used in court.

Recommendation: This section speaks only to the use of DNA in courts upon request by a convicted individual. This section should lay down standards for all instances of use of DNA in courts. Included in this, the provision should clarify that when DNA is used, corroborating evidence will be required in courts, and if confirmatory samples will be taken from defendants. Individuals should also have the right to have a second sample taken and re-analyzed as a check, and individuals must have a right to obtain re-analysis of crime scene forensic evidence in the event of appeal.

Inadequate privacy protections

Besides section 38 which requires that all DNA profiles, samples, and records are kept confidential, the Bill leaves all other privacy protections to be recommended by the DNA profiling Board.

Section 12(o) The Board shall exercise and discharge the following functions…“Making recommendation for provision of privacy protection laws, regulations and practices relating to access to, or use of, store DNA samples or DNA analyses with a view to ensure that such protections are sufficient.”

Recommendation: Basic privacy protections such as access, use, and storage of DNA samples should be written into the provisions of the Bill and not left as recommendations for the Board to make.

Missing Provisions

- Notification to the individual: There are no provisions that ensure that notification is given to an individual if his/her information is legally accessed or shared. Notification to the individual would be appropriate in section 36, which allows for the sharing of DNA profiles with foreign states, and section 35, which allows for the sharing of information with a court, tribunal, law enforcement agency, or DNA laboratory. As part of the notification, an individual should be given the right to appeal the decision.

- Consent: There are no provisions which speak to consent being taken from individuals whose DNA is collected. Consent must be taken from volunteers, missing persons (or their families), victims, and suspects. DNA can be taken compulsorily from offenders after they have been convicted. If an individual refuses to provide a DNA sample, a judge can override the decisions and order that a DNA sample be taken. In all cases that DNA is collected without consent, it must be clear that DNA evidence is directly relevant to the case.

- Right to request deletion of DNA profile from database: There are no provisions which give volunteers (children volunteers when they become adults), victims, and missing persons the right to request that their profile be deleted from the DNA database. This could be provided in section 37 which speaks to the expunction of records of acquitted convicts.

- Right of individuals to bring a private cause of action: There are no provisions which give the individual the right to bring a privacy cause of action for the unlawful storage of private information in the national, regional, or state DNA database. This is an important check against the unlawful collection, analysis, and storage of private genetic information on the database.

- Right to review one's personal data: There are no provisions that allow an individual to review his/her information contained on the state, regional, or national database. This is an important check against the unlawful collection, analysis, and storage of private genetic information on the database.

- Independence of DNA laboratories and DNA banks from the police: There are no provisions which ensure that DNA laboratories and DNA data banks remain independent from the police. This is an important check in ensuring against the tampering of DNA evidence.

- Established profiling standard: The Bill does not mandate the use of one single profiling standard. This is important in order to minimize false matches occurring by chance and to ensure consistency across DNA testing and profiling.

- Destruction of DNA samples: There are no provisions mandating that original samples of DNA be deleted. DNA samples should be destroyed once the DNA profiles needed for identification purposes have been obtained from them – allowing for sufficient time for quality assurance (six months). Furthermore, only a barcode and no identifying details should be sent to labs with samples for analysis.

Unique Identification Scheme (UID) & National Population Register (NPR), and Governance

This research was undertaken as part of the 'SAFEGUARDS' project that CIS is undertaking with Privacy International and IDRC.

Video

The above video is from the "UID, NPR, and Governance" conference held on March 2, 2013 at TERI, Bangalore.

What is the NPR?

In 2010, the Government of India initiated the NPR which entails the creation of the National Citizens Register. This register is being prepared at the local, sub-district, district, state and national level. The database will contain thirteen categories of demographic information and three categories of biometric data collected from all residents aged five and above. Collection of this information was initially supposed to take place during the House listing and Housing Census phase of Census 2011 during April 2010 to September 2010.[1]

What is the legal grounding of the NPR?

The NPR is legally grounded in the provisions of the Citizenship Act, 1955 and the Citizenship Rules 2003. It is mandatory for every usual resident in India to register in the NPR as per Section 14A of the Citizenship Act, 1955, as amended in 2004. The collection of biometrics is not accounted for in the statute or rules.

What are the objectives of the NPR?

The objectives of the NPR as stated by the Citizenship Act is for the creation of a National Citizen Register. The National Citizen Register is intended to assist in improving security by checking for illegal migration. Additional objectives that have been articulated include: providing services to the residents under government schemes and programmes, checking for identity frauds, and improving planning.[2]

What is the process of enrollment for the NPR?

NPR enrollment is being carried out through house to house canvassing. The Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, India has assigned Department of Information Technology (DIT) the responsibility of collecting and digitizing demographic data in 17 states and 2 Union Territories of India.[2] Collected information will then be printed and displayed in the local area where it is scrutinized by local officers and vetted by local bodies called ´Gram Sabha/Ward Committees´.[4] This process of social audit is meant to bring in transparency, equity, and ensure accuracy.

What information will be collected under the NPR?

The NPR database will include thirteen categories of demographic information and three categories of biometrics. The collection biometrics has not been provided for in the text of the Citizenship Rules, and is instead appears to be authorized through guidelines,[5] which do not have statutory backing. Currently, two iris scans, ten fingerprints, and a photograph are being collected. According to a 2010 Committee note, only the photograph and fingerprints were initially envisioned to be collected.

What is the Resident Identity Card?

The proposed Resident Identity card is a smart card with a micro-processor chip of 6.4 Kb capacity; the demographic and biometric attributes of each individual will be personalized in this chip. The UID number will be placed on the card as well. Currently, the government is only considering the possibility of distributing smart cards to all residents over the age of 18.[6]

What is the UID?

The Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) was established in January 2009 and is part of the Planning Commission of India. UIDAI aims to provide a unique 12 digit ID number to all residents in India on a voluntary basis. The number will be known as AADHAAR. The UIDAI will own and operate a Unique Identification Number database which will contain biometric and demographic data of citizens.[7]

What is the objective of the UID?

According to the UIDAI, the UID will provide identity for individuals. The scheme has been promoted by the UIDAI as enabling a number of social benefits including improving the public distribution system, enabling financial inclusion, and improving the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS). Despite these benefits, the UIDAI only guarantees identity, and does not guarantee rights, benefits or entitlement.[8]

What is the process for enrollment in the UID?

To enroll in the UID, individuals must go to enrollment centers with the appropriate documentation. Once documents are verified and biometrics taken, individuals will receive an acknowledgment slip and their UID number will be sent in the mail.[9] The UIDAI will enroll up to 600 million residents in 16 States and territories.[10] Online registration prior to enrollment at a Center is also now being offered.

How is UID being adopted by different States?

The adoption of the UID by different states and platforms has been controversial as the UID is not a mandatory number, yet with states and services adopting the number for different governmental services, the UID is becoming mandatory by default. Some ways in which states are using the UID include:

- Gas and vehicles: The UPA Government has required that citizens have a UID number for services such as purchasing cooking gas, issuing a RTI request, and registering vehicles.[11]

- Education: The Kerala government has required that all students must have UID number in order to be tracked through the system.[12] This mandate was questioned by the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights.

- First Information Reports (FIR’s): The high court in Bombay has ordered the state home department to direct all police stations in Maharashtra to record the Unique Identification (UID) numbers of accused individuals and witnesses filing a FIR.[13]

- Banks: The National Payment Corporation of India has collaborated UIDAI and is issuing ‘RuPay cards’ (Dhan Aadhaar cards) which will serve as ATM/micro-ATM cards. In 2011 the Bank of India had issued 250 cards.[14]

- Railway: Railways are proposing to use the UID database for bookings and validation of passengers.[15]

- Social Security: Commencing January 1, 2013, MGNREGA, the Rajiv Gandhi Awas Yojana (RGAY), the Ashraya housing scheme, Bhagyalakshmi and the social security and pension scheme have included the UID in the Mysore district

Has there been duplication of UID numbers?

According to news reports:

- The UIDAI has blacklisted an operator and a supervisor in Andhra Pradesh for issuing fake UID numbers.

- The UIDAI is looking into six complaints regarding the misuse of personal data while issuing the UID numbers to individuals.

- The UIDAI has received two received complaints regarding duplication of UID numbers.[17]

What are the differences between the UID and NPR?

- Voluntary vs. Mandatory: It is compulsory for all Indian residents to register with the NPR, while registration with the UIDAI is considered voluntary. However, the NPR will store individuals UID number with the NPR data and place it on the Resident Indian Card. In this way and others, the UID number is becoming compulsory by various means.

- Number vs. Register: UID will issue a number, while the NPR is the prelude to the National Citizens Register. Thus, it is only a Register. Though earlier the MNIC card was implemented along the coastal area, there has been no proposal to extend the MNIC to the whole country. The smart card that is proposed under the NPR has only been raised for discussion, and there has been no official decision to issue a card.

- Statute vs. Bill: The enrollment of individuals for the NPR is legally backed by the Citizenship Act, except in relation to the collection of biometrics, while the UID as proposed a bill which has not been passed for the legal backing of the scheme.

- Authentication vs. Identification: The UID number will serve as an authenticator during transactions. It can be adopted and made mandatory by any platform. The National Resident Card will signify resident status and citizenship. It is unclear what circumstances the card will be required for use in.

- UIDAI vs. RGI: The UIDAI is responsible for enrolling individuals in the UID scheme, and the RGI is responsible for enrolling individuals in the NPR scheme. It is important to note that the UIDAI is located in the Planning Commission, but its status is unclear, as the NIC had indicated that the data held is not being held by the government.

- Door to door canvassing vs. center enrollment: Individuals will have to go to an enrollment center and register for the UID, while the NPR will carry out part of the enrollment of individuals through door to door canvassing. Note: Individuals will still have to go to centers for enrolling their biometrics for the NPR scheme.

- Prior documentation vs. census material: The UID will be based off of prior forms of documentation and identification, while the NPR will be based off of census information.

- Online vs. Offline: For authentication of an individual’s UID number, the UID will require mobile connectivity, while the NPR can perform offline verification of an individual’s card.

What is the controversy between the UID and NPR?

- Effectiveness: There is controversy over which scheme would be more effective and appropriate for different purposes. For example, the Ministry of Home Affairs has argued that the NPR would be more suited for distributing subsidies than the UID, as the NPR has data linking each individual to a household.[18]

- Legality of sharing data: Both the legality of the UID and NPR collecting data and biometrics has been questioned. For example, it has been pointed out that the collection of biometric information through the NPR, is beyond the scope of subordinate legislation. Especially as this appears to be left only to guidelines.[19] Collection of any information under the UID scheme is being questioned as the Bill has not been approved by the Parliament.

- Accuracy: The UIDAI's use of multiple registrars and enrolment agencies, the reliance on 'secondary information' via existing ID documents for enrollment in the UID, and the original plan to enroll individuals via the 'introducer' system has raised by Home Minister Chidambaram in January 2012 about how accurate the data collected by the UID is is that will be collected.[20] To this extent, the UIDAI has changed the introducer system to a ‘verifier’ system. In this system, Government officials verify individuals and their documents prior to enrolling them.

- Biometrics: Though biometrics are mandatory for the UID scheme, according to information on the NPR website, if an individual has already enrolled with the UID, they will not need to provide their biometrics again for the NPR. Application of this standard has been haphazard as some individuals have been required to provide biometrics for both the UID and the NPR, and others have not been required to provide biometrics for the NPR.[21]

What court cases have been filed against the UID?

The following cases are currently filed in courts around the country:

- Supreme Court:

K S Puttaswamy, a retired judge of Karnataka High Court filed a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in the Supreme Court challenging the legality of UIDAI.[22]

- Chandigarh: A petition was filed in Chandigarh by Sanjeev Pandey which sought to quash executive order passed in violation of the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988, and Central Motor Vehicle Rules, 1989 by which UID cards had been made mandatory for registration of vehicles and grant of learner/regular driving license.[23]

- Karnataka: Mathew Thomas and Mr. VK Somasekhar have filed a civil suit in the Bangalore City Civil Courts (numbered 8181 of 2012) asking for the UID project to be stopped. The suit was dismissed, and they have appealed the case to the High Court (numbered 1780 and 1825 of 2013).

- Chennai: A PIL has been filed in the Madras High Court challenging the constitutional validity of the UIDAI and its issue of UID numbers.[24]

- Bombay: In January 2012 a case was filed in the Mumbai high Court. The petitioners to the case are R. Ramkumar, G. Nagarjuna, Kamayani Mahabal, Yogesh Pawar and Vickram Crishna & Ors.

What is the relationship between UID, NPR, and National Security

The UID and the NPR have both stated improving security as an objective for the projects. To this extent, it is envisioned that the UID and the NPR could be used to track and identify individuals, and determine if they are residents of India. In the case of the NPR, a distinction will be made between residents and citizens. Yet, concerns have also been raised that these projects instead raise national security threats, given the size of the databases that will be created, the centralized nature of the databases, the sensitive nature of the information held in the databases, and the involvement of international agencies.[25]

What is the relationship between UID and Big Data?

Aspects of the UID scheme allow it to generate a large amount of data from a variety of sources. Namely, the UID scheme aims to capture 12 billion fingerprints, 1.2 billion photographs and 2.4 billion iris scans and can be adopted by any platform. This data in turn can be stored, analyzed, and used for a number of purposes by a number of stakeholders in both the government and the private sectors. This is already happening to a certain extent as in November 2012 the UID established a Public Data Portal for the UID project. According to UIDAI officials the data portal will allow for big data analysis using crowd sourcing models.[26]

How is UID being used for BPL direct cash transfers?

Registration with the UID scheme is considered essential to determine whether beneficiaries belong in the BPL category and to provide transparency to the distribution of cash. In this way, the UID requirement is thought to prevent the leakage of social security benefits and subsidies to non-intended beneficiaries, as cash will only be made available to the person identified by the UID as the intended recipient. One of the main prerequisites of a below poverty line (BPL) direct cash transfer in India has become the registration with the UIDAI and the acquisition of a UID number. For example:

- The "Cash for Food" programme requires that individuals applying for aid have a bank account, and a UID number. The money is transferred, electronically and automatically, to the bank account and the beneficiary should be able to withdraw it from a micro-ATM using the UID number.[27] It is important to note that micro-ATMs are not actual ATMs, but instead are handheld machines which may give information on bank balance and such, but will not dispense or maintain privacy of transaction. Most importantly, the transaction is mediated though a banking correspondent.

- The government plans to cover the target BPL families and deposit USD 570 billion per year in the bank accounts of 100 million poor families by 2014.[28]

- Currently, only beneficiaries of thirteen government schemes and LPG connection holders have been identified as being entitled to register for a UID number.[29] Though these schemes have been identified, as of yet, adoption has happened in very few districts.

What are the concerns regarding the use of biometrics in the UID and NPR scheme?

Both the UID and the NPR rely on biometrics as a way to identify individuals. Yet, many concerns have been raised about the use of biometrics in terms of legality, effectiveness, and accuracy of the technology. With regards to the accuracy and effectiveness of biometrics – the following concerns have been raised:

- Biometrics are not infallible: Inaccuracies can arise from variations in individuals attributes and inaccuracies in the technology.

- Environment matters: An individual’s biometrics can change in response to a number of factors including age, environment, stress, activity, and illness.

- Population size matters: Because biometrics have differing levels of stability – the larger the population is the higher the possibility for error is.

- Technology matters: The accuracy of a biometric match also depends on the accuracy of the technology used. Many aspects of biometric technology can change including: calibration, sensors, and algorithms.

- Spoofing: It is possible to spoof a fingerprint and fool a biometric reader.[30]

[1]. Government of India. Ministry of Home Affairs. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner. http://bit.ly/IiySDh

[2]. This is according to a 2010 Cabinet note and the official website of the NPR.

[3]. Department of Information Technology: http://ditnpr.nic.in/frmStatelist.aspx - These include: (1) Arunachal Pradesh (2) Assam (3) Bihar (4) Chhattisgarh (5) Haryana (6) Himachal Pradesh (7)Jammu & Kashmir (8) Jharkhand (9) Madhya Pradesh (10)Meghalaya (11)Mizoram (12)Punjab (13)Rajasthan (14)Sikkim (15)Tripura (16)Uttar Pradesh (17)Uttarakhand Union Territories:-(1) Dadra & Nagar Haveli (2) Chandigarh.

[4]. Government of India. Ministry of Home Affairs. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner: http://bit.ly/IiySDh

[5]. Department of Information Technology. National Population Register. Question 22. What are the procedures to be followed for creating the NPR? The procedures to be followed for creating the NPR have been laid down in the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003, and the guidelines being issued from time to time.

[6]. The Unique Identification Government of India. Ministry of Home Affairs. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner: http://censusindia.gov.in/2011-Common/IntroductionToNpr.html Authority of India. http://uidai.gov.in/

[7]. Unique Identification Authority of India. http://uidai.gov.in/

[8]. The point was made by R. Ramachandran. How reliable is UID? Frontline. Volume 28- Issue 24: November 19- December 02, 2011. Available at: http://bit.ly/13UMiSv

[9]. For more information see: How to get an Aadhaar. http://bit.ly/R2jBOP

[10]. Mazumdar. R. UIDAI targets 400 million enrolments by mid 2013, Aadhar hopes to give unique identity to some 1.2 bn residents. Economic Times. December 2012. Available at: http://bit.ly/ZC3Yve. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[11]. Malu. B. The Aadhaar Card – What are the real intentions of the UPA Government? DNA. February 18th 2013. Available at: http://bit.ly/150BXRj. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[12]. Government of Kerala. General Education Department Circular No. 52957/G2?2012/G.Edn. Available at: http://bit.ly/15Oiq8J

[13]. Plumber, M. Make UID numbers must in FIRs: Bombay HC. DNA. October 2011. Available at: http://bit.ly/tVsInl. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[14]. Press Information Bureau. Government of India. Identity Card to Every Adult Resident of the Country under NPR; No Card being issued by UIDAI. December 2011. Available at: http://bit.ly/tJwZG1

[15]. TravelBiz. Railways to use Aadhar database for passenger validation. February 2013. Available at: http://bit.ly/YcW5wl. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[16]. Vombatkere. S.G. Questions for Mr. Nilekani. The Hindu. February 2013. Available at: http://bit.ly/YqPlK1. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[17]. Economic Times. UIDAI orders probe into duplication of Aadhaar numbers. http://bit.ly/ZORowg. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[18]. Jain. B. Battle over turf muddies waters. Times of India. February 2013. Available at: http://bit.ly/16ud3gm. Last accessed: February 28th 2013

[19]. Rediff. Aadhaar’s allocation is Parliament’s contempt. February 2013. Available at: http://bit.ly/Y638JS. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[20]. Ibid 17.

[21]. Times of India. Confused over Aadhaar, Cabinet clears GoM. February 2013. Available at http://bit.ly/UTH2JS. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[22]. Times of India. Supreme Court notice to govt on PIL over Aadhar. December 2012. Available at: http://bit.ly/13UNs0i. Last accessed: February 2013.

[23]. The Indian Express. HC issues notice to Centre, UT over mandatory UID for license. January 2013. Available at: http://bit.ly/WJq43M. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[24]. Economic Times. PIL seeks to scrap Nandan Nilekani’s Aadhar project. January 2012. Available at: http://bit.ly/zB1H07. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[25]. Times of India. UID poses national security threat: BJP. January 2012. Available at: http://bit.ly/WeM6KA. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[26]. Zeenews. UIDAI launches Public Data Portal for Aadhaar. November 8th 2012. Available at: http://bit.ly/T9NdX3. Last Accessed: November 12th 2012.

[27]. Punj, S. Wages of Haste: Implementing the cash transfer scheme is proving a challenge. January 2013. Available at: http://bit.ly/1024Dwo. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[28]. The International Business Times. India to Roll Out World’s Biggest Direct Cash Transfer Scheme for the Poor. November 2012. Available at: http://bit.ly/UYbtw4. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[29]. Mid Day. Do not register for Aadhaar card before March 15: UID in –charge. February 2013. Available at: http://bit.ly/Xymx9d. Last accessed: February 28th 2013.

[30]. These points were raised in the following frontline article Ibid: Ramachandran, R. How reliable is UID? Frontline. Volume 28 – Issue 24 November 19th – December 2nd 2011. Available at: http://bit.ly/13UMiSv. Last accessed February 28th 2013.

Summary of the CIS workshop on the Draft Human DNA Profiling Bill 2012

This research was undertaken as part of the 'SAFEGUARDS' project that CIS is undertaking with Privacy International and IDRC.

Think you control who has access to your DNA data? That might just be a myth of the past. Today, clearly things have changed, as draft Bills with the objective of creating state, regional, and national DNA databases in India have been leaked over the last years. Plans of profiling certain residents in India are being unravelled as, apparently, the new policy when collecting, handling, analysing, sharing and storing DNA data is that all personal information is welcome; the more, the merrier!

Who is behind all of this? The Centre for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics in India created the 2007 draft DNA Profiling Bill[1], with the aim of regulating the use of DNA for forensic and other purposes. In February 2012 another draft of the Bill was leaked which was created by the Department of Biotechnology. The most recent version of the Bill was drafted in April 2012 and seeks to create DNA databases at the state, regional and national level in India[2]. According to the latest 2012 draft Human DNA Profiling Bill, each DNA database will contain profiles of victims, offenders, suspects, missing persons and volunteers for the purpose of identification in criminal and civil proceedings. The Bill also establishes a process for certifying DNA laboratories, and a DNA Profiling Board for overseeing the carrying out of the Act.

However, the 2012 draft Human DNA Profiling Bill lacks adequate safeguards and its various loopholes and overreaching provisions could create a potential for abuse. The creation of DNA databases is currently unregulated in India and although regulations should be enacted to prevent data breaches, the current Bill raises major concerns in regards to the collection, use, analysis and retention of DNA samples, DNA data and DNA profiles. In other words, the proposed DNA databases would not only be restricted to criminals…

DNA databases...and Justice for All?

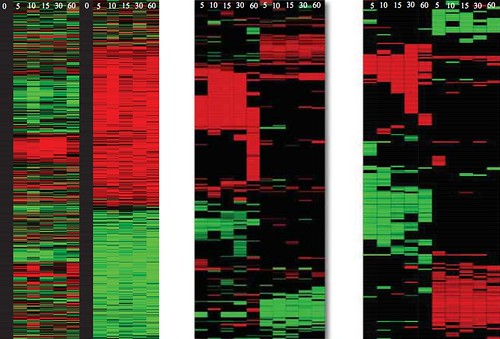

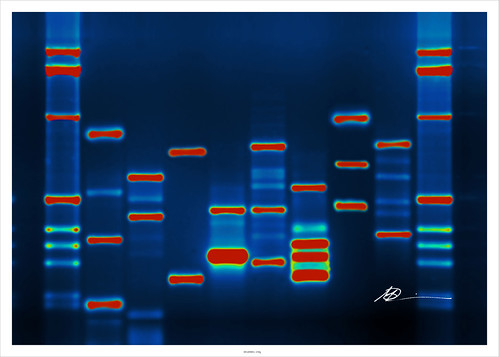

Source: Libertas Academica on flickr

During the workshop [3]on the 2012 draft Human DNA Profiling Bill, DNA[4] was defined as a material that determines a persons´ hereditary traits, whilst DNA profiling[5] was defined as the processing and analysis of unique sequences of parts of DNA. Thus the uniqueness of DNA data is clear and the implications that could potentially occur through its profiling could be tremendous. The 2007 DNA Profiling Bill has been amended, yet its current 2012 version appears not only to be more intrusive, but to also be extremely vague in terms of protecting data, whilst very deterministic in regards to the DNA Profiling Board´s power. A central question in the meeting was:

Should DNA databases be created at all?

The following concerns were raised and discussed during the workshop:

● The myth of the infallibility of DNA evidence

The Innocence Project[6], which was presented at the workshop, appears to provide an appeal towards the storage of DNA samples and profiles, as it represents clients seeking post-conviction DNA testing to prove their innocence. According to statistics presented at the workshop, there have been 303 post-conviction exonerations in the United States, as a result of individuals proving their innocence through DNA testing. Though post-conviction exonerations can be useful, they cannot be the basis and main justification for creating DNA databases. Although DNA testing could enable post-conviction exonerations, errors in matching data remain a high probability and could result in innocent people being accused, arrested and prosecuted for crimes they did not commit. Thus, arguments towards the necessity and utility of the creation of DNA databases in India appear to be weak, especially since DNA evidence is not infallible[7].

False matches can occur based on the type of profiling system used, and errors can take place in the chain of custody of the DNA sample, all of which indicate the weakness of DNA evidence being used. DNA data only provides probabilities of potential matches between DNA profiles and the larger the amount of DNA data collected, the larger the probability of an error in matching profiles[8].

● The non-criteria of DNA data collection

How and when can DNA data be collected? The amended draft 2012 Bill remains extremely vague and broad. In particular, the Bill states that all offences under the Indian Penal Code and other laws, such as the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956, are applicable instances of human DNA profiling. Section B(viii) of the Schedule states that human DNA profiling will be applicable for offences under ´any other law as may be specified by the regulations made by the Board´. This incredibly vague section empowers the DNA Profiling Board with the ultimate power to decide upon the offences under which DNA data will be collected. The issue is this: most laws have loopholes. A Bill which lists applicable instances of human DNA profiling, under the umbrella of a potentially indefinite number of laws, exposes individuals to the collection of their DNA data, which could lead to potential abuse.

● The DNA Profiling Board´s power

The DNA Profiling Board has ´absolute´ power, especially according to the 2012 draft Human DNA Profiling Bill. Some of the Board´s functions include providing recommendations for provision of privacy protection laws, regulations and practices relating to access to, or use of, stored DNA samples or DNA analyses[9]. The Board is also required to advise on all ethical and human rights issues, as well as to take ´necessary steps´ to protect privacy. However, it remains unclear how a Board which lacks human rights expertise will carry out such tasks.

No human rights experts

Despite the various amendments[10] to the section on the composition of the Board, no privacy or human rights experts have been included. According to the Bill, the Board will be comprised of many molecular biologists and other scientists, while human rights experts have not been included to the list. This can potentially be problematic as a lack of expertise on privacy and human rights laws can lead to the regulation of DNA databases without taking civil liberties into consideration.

Vague authorisation for communication of DNA profiles

The Bill also empowers the Board to ´authorise procedures for communication of DNA profiles for civil proceedings and for crime investigation by law enforcement and other agencies´[11]. Although the 2007 Bill [12]restricted the Boards´ authorisation to crime investigation by law enforcement agencies, its 2012 amendment extends such authorisation to ´civil proceedings´ which can also be carried out by so-called ´other agencies´.[13] This amendment raises concerns, as the ´other agencies´ and the term ´civil proceedings´ remain vague.

Protecting the public

The Board is also authorised to ´assist law enforcement agencies in using DNA techniques to protect the public´[14]. Over the last years, laws are being enacted that enable law enforcement agencies to use technologies for surveillance purposes in the name of ´public security´, and the 2012 draft Bill is no exception. Many security measures have been applied to ´protect the public´, such as CCTV cameras and other technologies, but their actual contribution to public safety still remains a controversial debate[15]. DNA techniques which would effectively protect the public have not been adequately proven, thus it remains unclear how the Board would assist law enforcement agencies.

Sharing data with international agencies…and regulating DNA laboratories

In addition to the above, the Board would also encourage cooperation between Indian investigation agencies and international agencies[16]. This would potentially enable the sharing of DNA data between third parties and would enhance the probability of data being leaked to unauthorised third parties.

The Board would also be authorised to regulate the standards, quality control and quality assurance obligations of the DNA laboratories[17]. The draft 2012 Bill ultimately gives monopolistic control to the DNA Profiling Board over all the procedures related to the handling of DNA data!

● The DNA Data Bank Manager

According to the 2012 draft Human DNA Profiling Bill[18], it is the DNA Data Bank Manager who would carry out ´all operations of and concerning the National DNA Data Bank´. All such operations are not clearly specified. The powers and duties that the DNA Data Bank Manager would be expected to have are not specified in the Bill, which merely states that they would be specified by regulations made by the DNA Profiling Board.

The Bill also empowers the Manager to determine appropriate instances for the communication of information[19]. In other words, law enforcement agencies and DNA laboratories can request the disclosure of information from the DNA Data Bank Manager, without prior authorisation. The DNA Data Bank Manager is empowered to decide the requested data.

- DNA access restrictions

Are you a victim or a cleared suspect? You better be, if you want access to your data to be restricted! The 2012 draft Human DNA Profiling Bill [20]states that access to information will be restricted in cases when a DNA profile derives from a victim or a person who has been excluded as a suspect. The Bill is unclear as to how access to the data of non-victims or suspects is regulated.

● Availability of DNA profiles and DNA samples

According to the amended draft 2012 Bill[21], DNA profiles and samples can be made available in criminal cases, judicial proceedings and for defence purposes among others. However, ´criminal cases´ are loosely defined and could enable the availability of DNA data in low profile cases. Furthermore, the availability of DNA data is also enabled for the ´creation and maintenance of a population statistics database´. This is controversial because it remains unclear how such a database would be used.

● Data destruction

According to an amendment to section 37, DNA data will be kept on a ´permanent basis´ and the DNA Data Bank Manager will expunge a DNA profile only once the court has certified that an individual is no longer a suspect. This raises major concerns, as it does not clarify under what conditions individuals can have access to their data during its retention, nor does it give volunteers and missing persons the opportunity to have their data deleted from the data bank.

Workshop conclusions

Source: micahb37 on flickr

The various loopholes in the Bill which can create a potential for abuse were discussed throughout the workshop, as well as various issues revolving around DNA data retention, as previously mentioned.

During the workshop, some participants questioned the creation of DNA databases to begin with, while others argued that they are inevitable and that it is not a question of whether they should exist, but rather a question of how they should be regulated. All participants agreed upon the need for further safeguards to protect individuals´ right to privacy and other human rights. Further research on the necessity and utility of the creation of DNA databases in regards to human rights was recommended. In addition to all the above, the Ministry of Law and Justice was recommended to pilot the draft DNA Profiling Bill to ensure better provisions in regards to privacy and data protection.

A debate on the use of DNA data in civil cases versus criminal cases was largely discussed in the workshop, with concerns raised in regards to DNA sampling being enabled in civil cases. The fact that the terms ´civil cases´ and ´criminal cases´ remain broad, vague and not legally-specified, raised huge concerns in the workshop as this could enable the misuse of DNA data by authorities. Thus, the members attending the workshop recommended the creation of two separate Bills regulating the use of DNA data: a DNA Profiling Bill for Criminal Investigation and a DNA Profiling Bill for Research. The creation of such Bills would restrict the access to, collection, analysis, sharing of and retention of DNA data to strictly criminal investigation and research purposes.

However, even if separate Bills were created, who is to say that when implemented DNA in the database would not be abused? Criminal investigations can be loosely defined and research purposes can potentially cover anything and everything. So the question remains:

Should DNA databases be created at all?

[1] Draft DNA Profiling Bill 2007, http://dbtindia.nic.in/DNA_Bill.pdf

[2] Human DNA Profiling Bill 2012: Working draft versión – 29th April 2012,

[3] Centre for Internet and Society, Analyzing the Draft Human DNA Profiling Bill 2012, 25 February 2013, http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/events/analyzing-draft-human-dna-profiling-bill

[4] Genetics Home Reference: Your Guide to Understanding Genetic Conditions, What is DNA?, http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/handbook/basics/dna

[5] Shanna Freeman, How DNA profiling Works, http://science.howstuffworks.com/dna-profiling.htm

[6] Innocence Project, DNA exoneree case profiles, http://www.innocenceproject.org/know/

[7] Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC), Essentially Yours: The Protection of Human Genetic Information in Australia (ALRC Report 96), ´Criminal Proceedings: Reliability of DNA evidence´, Chapter 44, http://www.alrc.gov.au/publications/44-criminal-proceedings/reliability-dna-evidence

[8] Ibid.

[9] Human DNA Profiling Bill 2012: Working draft version – 29th April 2012, Section 12(o, p, t), http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/draft-dna-profiling-bill-2012.pdf

[10] Ibid: Section 4(q)

[11] Ibid: Section 12(j)

[12] Draft DNA Profiling Bill 2007, Section 13, http://dbtindia.nic.in/DNA_Bill.pdf

[13] : Human DNA Profiling Bill 2012: Working draft version – 29th April 2012, Sections 12(j), http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/draft-dna-profiling-bill-2012.pdf

[14] Ibid: Section 12(l)

[15] Schneier, B.(2008), Schneier on Security, ´CCTV cameras´, http://www.schneier.com/blog/archives/2008/06/cctv_cameras.html

[16] Human DNA Profiling Bill 2012: Working draft version – 29th April 2012, Sections 12(u) and 12(v), http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/draft-dna-profiling-bill-2012.pdf

[17] Ibid: Section on the ´Standards, Quality Control and Quality Assurance Obligations of DNA Laboratories´

[18] Ibid: Section 33

[19] Ibid: Section 35

[20] Ibid: Section 43

[21] Ibid: Section 40

A Comparison of the Draft DNA Profiling Bill 2007 and the Draft Human DNA Profiling Bill 2012

This research was undertaken as part of the 'SAFEGUARDS' project that CIS is undertaking with Privacy International and IDRC.

Last April, the most recent version of the DNA Profiling Bill was leaked in India. The draft 2007 DNA Profiling Bill failed to adequately regulate the collection, use, sharing, analysis and retention of DNA samples, profiles and data, whilst its various loopholes created a potential for abuse. However, its 2012 amended version is not much of an improvement. On the contrary, it excessively empowers the DNA Profiling Board, while remaining vague in terms of collection, use, analysis, sharing and storage of DNA samples, profiles and data. Due to its ambiguity and lack of adequate safeguards, the draft April 2012 Human DNA Profiling Bill can potentially enable the infringement of the right to privacy and other human rights.

Draft 2007 DNA Profiling Bill vs. Draft 2012 Human DNA Profiling Bill

1. Composition of the DNA Profiling Board

Amendment: The Draft 2007 DNA Profiling Bill listed the members which would be appointed by the Central Government to comprise the DNA Profiling Board. A social scientist of national eminence, as stated in section 4(q) of Chapter 3, was included. However, the specific section has been deleted from the Draft 2012 Human DNA Profiling Bill and no other social scientist has been added to the list of members to comprise the DNA Profiling Board. Despite the amendments to the section on the composition of the Board, no privacy or human rights expert has been included.

Analysis: The lack of human rights experts on the board can potentially be problematic as a lack of expertise on privacy laws and other human rights laws can lead to the regulation of DNA databases without taking privacy and other civil liberties into consideration.

- DNA 2007 Bill (Section 4): “The DNA Profiling Board shall consist of the following members appointed by the Central Government from amongst persons of ability, integrity and standing who have knowledge or experience in DNA profiling including molecular biology, human genetics, population biology, bioethics , social sciences, law and criminal justice or any other discipline which would, in the opinion of the Central Government, be useful to DNA Profiling , namely: (a) a Renowned Molecular Biologist to be appointed by the Central Government Chairperson, (b) Secretary, Ministry of Law and Justice, or his nominee ex-officio Member; (c) Chairman, Bar Council of India, New Delhi or his nominee ex-officio Member; (d) Vice Chancellor, NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad ex-officio Member; (e) Director, Central Bureau of Investigation or his nominee ex-officio Member; (f) Chief Forensic Scientist, Directorate of Forensic Science, Ministry of Home Affairs, New Delhi ex-officio Member; (g) Director, National Crime Records Bureau, New Delhi ex-officio Member; (h) Director, National Institute of Criminology and Forensic Sciences, New Delhi ex-officio Member; (i) a Forensic DNA Expert to be nominated by Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs, New Delhi, Government of India Member; (j) a DNA Expert from All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi to be nominated by its Director, Member; (k) a Population Geneticist to be nominated by the President, Indian National Science Academy, New Delhi Member; (l) an Expert to be nominated by the Director, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore Member; (m) Director, National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration of Laboratories, New Delhi ex-officio Member; (n) Director, Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Hyderabad ex-officio Member; (o) Representative of the Department of Bio-technology, Government of India, New Delhi to be nominated by Secretary, DBT, Ministry of S&T, Government of India Member; (p) The Chairman, National Bioethics Committee of Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, New Delhi ex-officio Member; (q) a Social Scientist of National Eminence to be nominated by Secretary, MHRD, Government of India Member; (r) four Directors General of Police representing different regions of the country to be nominated by MHA Members; (s) two expert Members to be nominated by the Chairperson Members (t) Manager, National DNA Data Bank ex-officio Member; (u) Director, Centre for DNA and Fingerprinting and Diagnostics (CDFD), Hyderabad ex-officio Member Secretary”

- DNA April 2012 Bill (Section 4):“The Board shall consist of the following Members appointed from amongst persons of ability, integrity and standing who have knowledge or experience in DNA profiling including molecular biology, human genetics, population biology, bioethics, social sciences, law and criminal justice or any other discipline which would be useful to DNA profiling, namely:- (a) A renowned molecular biologist to be appointed by the Central Government- Chairperson; (b) Vice Chancellor of a National Law University established under an Act of Legislature to be nominated by the Chairperson- ex-officio Member; (c) Director, Central Bureau of Investigation or his nominee (not below the rank of Joint Director)- ex-officio Member; (d) Director, National Institute of Criminology and Forensic Sciences, New Delhi- ex-officio Member;(e) Director General of Police of a State to be nominated by Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India- ex-officio Member; (f) Chief Forensic Scientist, Directorate of Forensic Science, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India - ex-officio Member (g) Director of a Central Forensic Science Laboratory to be nominated by Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India- ex-officio Member; (h) Director of a State Forensic Science Laboratory to be nominated by Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India- ex-officio Member; (i) Chairman, National Bioethics Committee of Department of Biotechnology, Government of India- ex-officio Member; (j) Director, National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration of Laboratories, New Delhi- exofficio Member; (k) Financial Adviser, Department of Biotechnology, Government of India or his nominee- ex-officio Member; (l) Two molecular biologists to be nominated by the Secretary, Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India- Members; (m) A population geneticist to be nominated by the President, Indian National Science Academy, New Delhi- Member; (n) A representative of the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India to be nominated by the Secretary, Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of India- Member; (o) Director, Centre for DNA and Fingerprinting and Diagnostics (CDFD), Hyderabad- ex-officio Member- Secretary”

2. Powers and functions of the Chief Executive Officer

Amendment: Although the Chief Executive Officer´s (CEO) powers and functions are set out in the 2007 Draft DNA Bill, these have been deleted from the amended 2012 Draft Bill. The Draft 2012 Bill merely states how the CEO will be appointed, the CEO´s status and that the CEO should report to the Member Secretary of the Board. As for the powers and functions of the CEO, the 2012 Bill states that they will be specified by the Board, without any reference to what type of duties the CEO would be eligible for. Furthermore, section 10(3) has been added which determines that the CEO will be ´a scientist with understanding of genetics and molecular biology´.

Analysis: The lack of legal guidelines which would determine the scope of such regulations indicates that the CEO´s power is subject to the Board. This could create a potential for abuse, as the CEO´s power and the criteria for the creation of the regulations by the Board are not legally specified. Although an understanding of genetics and molecular biology is a necessary prerequisite for the specific CEO, an official understanding of privacy and human rights laws should also be a prerequisite to ensure that tasks are carried out adequately in regards to privacy and data protection.

- DNA 2007 Bill (Section 11):“(1) The DNA Profiling Board shall have a Chief Executive Officer who shall be appointed by the Selection Committee consisting of Chairperson and four other members nominated by the DNA Profiling Board. (2) The Chief Executive Officer shall be of the rank of Joint Secretary to the Govt. of India and report to the Member Secretary of the DNA Profiling Board. (3)The Chief Executive Officer appointed under sub-section (1)shall exercise powers of general superintendence over the affairs of the DNA Profiling Board and its day-to-day management under the direction and control of the Member Secretary. (4) The Chief Executive Officer shall be responsible for the furnishing of all returns, reports and statements required to be furnished, under this Act and any other law for the time being in force, to the Central Government. (5) It shall be the duty of the Chief Executive Officer to place before the DNA Profiling Board for its consideration and decision any matter of financial importance if the Financial Adviser suggests to him in writing that such matter be placed before the DNA Profiling Board.”

- DNA April 2012 Bill (Section 10): “(1) There shall be a Chief Executive Officer of the Board who shall be appointed by a selection committee consisting of the Chairperson and four other Members nominated by the Board. (2) The Chief Executive Officer shall be a person not below the rank of Joint Secretary to the Government of India or equivalent and he shall report to the Member-Secretary of the Board. (3) The Chief Executive Officer shall be a scientist with understanding of genetics and molecular biology. (4) The Chief Executive Officer appointed under subsection (1) shall exercise such powers and perform such duties, as may be specified by the regulations made by the Board, under the direction and control of the Member-Secretary”

3. Functions of the Board

Amendment: The section on the functions of the DNA Profiling Board of the 2007 Draft DNA Profiling Bill has been amended. In particular, sub-section 12(j) of the Draft 2012 Human DNA Profiling Bill states that the Board would ´authorise procedures for communication of DNA profile for civil proceedings and for crime investigation by law enforcement and other agencies´. The equivalent sub-section in the 2007 Draft DNA Bill restricted the Board´s authorisation to crime investigation by law enforcement agencies, and did not include civil proceedings and other agencies.

Analysis: This amendment raises concerns, as the ´other agencies´ and the term ´civil proceedings´ are not defined and remain vague. The broad use of the terms ´other agencies´ and ´civil proceedings´ could create a potential for abuse, as it is unclear which parties would be authorised to use DNA profiles and under what conditions, nor is it clear what ´civil proceedings´ entail.

DNA 2007 Bill (Section 13(x)): The DNA Profiling Board constituted under section 3 of this Act shall exercise and discharge the following powers and functions, namely: “authorize communication of DNA profile for crime investigation by law enforcement agencies;”

DNA April 2012 Bill (Section 12(j)): The Board shall exercise and discharge the following functions for the purposes of this Act, namely: “authorizing procedures for communication of DNA profile for civil proceedings and for crime investigation by law enforcement and other agencies;”

4. Regional DNA Data Banks

Amendment: Section 33(1) of the 2007 Draft DNA Profiling Bill has been amended and its 2012 version (section 32(1)) states that the Central Government will establish a National DNA Data Bank and ´as many Regional DNA Data Banks thereunder, for every state or group of States, as necessary´.

Analysis: This amendment enables the potential establishment of infinite regional DNA Data Banks without setting out the conditions for their function, how they would use data, how long they would retain it for or who they would share it with. The establishment of such regional data banks could potentially enable the access to, analysis, sharing and retention of huge volumes of DNA data without adequate regulatory frameworks restricting their function.

- DNA 2007 Bill (Section 33(1)): “The Central Government shall, by a notification published in the Gazette of India, establish a National DNA Data Bank.”

- DNA April 2012 Bill (Section 32(1)): “The Central Government shall, by notification, establish a National DNA Data Bank and as many Regional DNA Data Banks thereunder for every State or a group of States, as necessary.

5. Data sharing

Section 33(2) of the 2007 Draft DNA Profiling Bill has been amended and section 32(2) of the 2012 draft Human DNA Profiling Bill includes that every state government should establish a State DNA Data Bank which should share the information with the National DNA Data Bank.

This sharing of DNA data between state and national DNA Data Banks could potentially increase the probability of data being accessed, shared, analysed and retained by unauthorised third parties. Furthermore, specific details, such as which information should be shared, how often and under what conditions, have not been specified.

- DNA 2007 Bill (Section 33(2)): “A State Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, establish a State DNA Data Bank.”

- DNA April 2012 Bill (Section 32(2)):“Every State Government may, by notification, establish a State DNA Data Bank which shall share the information with the National DNA Data Bank.”

6. Data retention

Amendment: Section 32(3) of the 2012 draft DNA Bill has been amended from its original 2007 form to include that regulations on the retention of DNA data would be drafted by the DNA Profiling Board.

Analysis: This amendment does not set out the DNA data retention period, nor who would have the authority to access such data and under what conditions. Furthermore, regulations on the retention of such data would be drafted by the DNA Profiling Board, which could increase their probability of being subject to bias and lack of transparency.

- DNA 2007 Bill (Section 33(3)): “The National DNA Data Bank shall receive DNA data from State DNA Data Banks and shall store the DNA Profiles received from different laboratories in the format as may be specified by regulations.”

- DNA April 2012 Bill (Section 32(3)): “The National DNA Data Bank shall receive DNA data from State DNA Data Banks and shall store the DNA profiles received from different laboratories in the format as may be specified by the regulations made by the Board.”

7. Data Bank Manager

Amendment: Section 33 has been added to the 2012 draft Human DNA Profiling Bill and establishes a DNA Data Bank Manager, who would carry out ´all operations of and concerning the National DNA Data Bank´.

Analysis: All such operations are not clearly specified and could create a potential for abuse. The DNA Data Manager would have the same type of status as the Chief Executive Officer, but he/she would be required to have an understanding of computer applications and statistics, possibly to support data mining efforts. However, the powers and duties that the DNA Data Bank Manager would be expected to have are not specified in the Bill, which merely states that they would be specified by regulations made by the DNA Profiling Board.

- DNA 2012 Bill (Section 33):“(1) All operations of and concerning the National DNA Data Bank shall be carried out under the supervision of a DNA Data Bank Manager who shall be appointed by a selection committee consisting of Chairperson and four other Members nominated by the Board.(2) The DNA Data Bank Manager shall be a person not below the rank of Joint Secretary to the Government of India or equivalent and he shall report to the Member-Secretary of the Board.(3) The DNA Data Bank Manager shall be a scientist with understanding of computer applications and statistics. (4) The DNA Data Bank Manager appointed under sub-section (1) shall exercise such powers and perform such duties, as may be specified by the regulations made by the Board, under the direction and control of the Member-Secretary.”

8. Communication of DNA profiles to foreign agencies

Amendment: The 2007 Draft DNA Profiling Bill has been amended and sub-sections 35(2, 3) have been excluded from the 2012 Draft Human DNA Profiling Bill. These sub-clauses prohibited the use of DNA profiles for purposes other than the administration of the Act, as well as the communication of DNA profiles. Furthermore, sub-section 36(1) has been added to the 2012 Bill, which authorises the communication of DNA profiles to international agencies for the purposes of crime investigation.

Analysis: The exclusion of sub-sections 35(2, 3) from the 2012 Bill indicates that the use and communication of DNA profiles without prior authorisation may be legally permitted, which raises major privacy concerns. Sub-section 36(1) does not define a ´crime investigation´, which indicates that DNA profiles could be shared with international agencies for loosely defined ´criminal investigations´ or even for civil proceedings. The lack of a strict definition to the term ´crime investigation´, as well as the broad reference to foreign states and international agencies raises concerns, as it remains unclear who will have access to information, for how long, under what conditions and whether that data will be retained.

- DNA 2007 Bill (Sections 35(2,3)): “(2) No person who receives the DNA profile for entry in the DNA Data Bank shall use it or allow it to be used for purposes other than for the administration of this Act. (3) No person shall, except in accordance with the provisions hereinabove, communicate or authorize communication, or allow to be communicated a DNA profile that is contained in the DNA Data Bank or information that is referred to in sub-section (1) of Section 34”