Blog

Understanding IANA Stewardship Transition

NTIA Announcement and ICANN-convened Processes:

On 14 March 2014, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) of the US Government announced “its intent to transition key Internet domain name functions to the global multistakeholder community”. These key Internet domain name functions refer to the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) functions. For this purpose, the NTIA asked the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) to “convene global stakeholders to develop a proposal to transition the current role played by NTIA in the coordination of the Internet’s domain name system (DNS)”. This was welcome news for the global Internet community, which has been criticising unilateral US Government oversight of Critical Internet Resources for many years now. NTIA further announced that IANA transition proposal must have broad community support and should address the following four principles:

- Support and enhance the multistakeholder model;

- Maintain the security, stability, and resiliency of the Internet DNS;

- Meet the needs and expectation of the global customers and partners of the IANA services; and

- Maintain the openness of the Internet.

Subsequently, during ICANN49 in Singapore (March 23-27, 2014), ICANN held flurried discussions to gather initial community feedback from participants to come up with a Draft Proposal of the Principles, Mechanisms and Process to Develop a Proposal to Transition NTIA’s Stewardship of the IANA Functions on 8 April 2014, which was open to public comments until 8 May 2014, which was further extended to 31 May 2014. Responses by various stakeholders were collected in this very short period and some of them were incorporated into a Revised Proposal issued by ICANN on 6th June 2014. ICANN also unilaterally issued a Scoping Document defining the scope of the process for developing the proposal and also specifying what was not part of the scope. This Scoping Document came under severe criticism by various commentators, but was not amended.

ICANN also initiated a separate but parallel process to discuss enhancement of its accountability on 6 May 2014. This was launched upon widespread distress over the fact that ICANN had excluded its role as operator of IANA functions from the Scoping Document, as well as over questions of accountability raised by the community at ICANN49 in Singapore. In the absence of ICANN’s contractual relationship with NTIA to operate the IANA functions, it remains unclear how ICANN will stay accountable upon the transition. The accountability process looks to address the same through the ICANN community. The issue of ICANN accountability is then envisioned to be coordination within ICANN itself through an ICANN Accountability Working Group comprised of community members and a few subject matter experts.

What are the IANA Functions?

Internet Assigned Numbers Authority, or IANA functions consist of three separate tasks:

- Maintaining a central repository for protocol name and number registries used in many Internet protocols.

- Co-ordinating the allocation of Internet Protocol (IP) and Autonomous System (AS) numbers to the Regional Internet Registries, who then distribute IP and AS numbers to ISPs and others within their geographic regions.

- Processing root zone change requests for Top Level Domains (TLDs) and making the Root Zone WHOIS database consisting of publicly available information for all TLD registry operators.

The first two of the abovementioned functions are operated by ICANN in consonance with policy developed at the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and Address Supporting Organisation (ASO) respectively, both of which exist under the ICANN umbrella.

The performance of last of these functions is distributed between ICANN and Verisign. NTIA has a Cooperative Agreement with Verisign to perform the related root zone management functions. The related root zone management functions are the management of the root zone “zone signing key” (ZSK), as well as implementation of changes to and distribution of the DNS authoritative root zone file, which is the authoritative registry containing the lists of names and addresses for all top level domains.

Currently, the US Government oversees this entire set of operations by contracting with ICANN as well as Verisign to execute the IANA functions. Though the US Government does not interfere generally in operations of either ICANN or Verisign in their role as operators of IANA functions, it cannot be denied that it exercises oversight on both the operators of IANA functions, through these contracts.

Import of the NTIA Announcement:

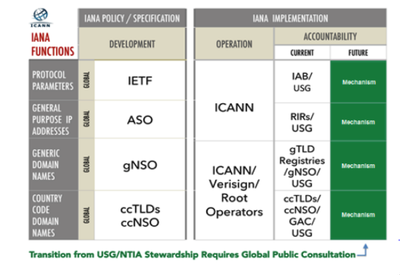

The NTIA announcement of 14th March intends to initiate the withdrawal of such oversight of IANA functions by the NTIA in order to move towards global multistakeholder governance. NTIA has asked ICANN to initiate a process to decide upon what such global multistakeholder governance of IANA functions may look like. The following diagram presents the current governance structure of IANA functions and the areas that the NTIA announcement seeks to change:

The IANA Oversight Mechanism (Source)

What does the NTIA Announcement NOT DO?

The NTIA announcement DOES NOT frame a model for governance of IANA functions once it withdraws its oversight role. NTIA has asked ICANN to convene a process, which would figure the details of IANA transition and propose an administrative structure for IANA functions once the NTIA withdraws its oversight role. But what this new administrative structure would look like has not itself been addressed in the NTIA announcement. As per the NTIA announcement, the new administrative structure is yet to be decided by a global multistakeholder community in accordance with the four principles outlined by the NTIA through a process, which ICANN shall convene.

The NTIA announcement DOES NOT limit discussions and participation in IANA transition process to within the ICANN community. NTIA has asked ICANN to convene “global stakeholders to develop a proposal to transition” IANA functions. This means all global stakeholders participation, including that of Governments and Civil Society is sought for the IANA transition process. ICANN has been asked “to work collaboratively with the directly affected parties, including the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), the Internet Architecture Board (IAB), the Internet Society (ISOC), the Regional Internet Registries (RIRs), top level domain name operators, VeriSign, and other interested global stakeholders”, in the NTIA announcement. This however does not signify that discussions and participation in development of proposal for IANA transition needs to be limited to the ICANN community or the technical community. In fact, ICANN has itself said that the list of events provided as “Timeline of Events” in its Draft Proposal of 8 April 2014 for engagement in development of a proposal for IANA transition is non-exhaustive. This means proposal for IANA transition can be developed by different stakeholders, including governments and civil society in different fora appropriate to their working, including at the IGF and WSIS+10.

The NTIA announcement DOES NOT mean devolution of IANA functions administration upon ICANN. NTIA chooses ICANN and Verisign to operate the IANA functions. If NTIA withdraws from its role, the question whether ICANN or Verisign should operate the IANA functions at all becomes an open one, and should be subject to deliberation. By merely asking ICANN to convene the process, the NTIA announcement in no way assigns any administration of IANA functions to ICANN. It must be remembered that the NTIA announcement says that key Internet domain name functions shall transition to the global multistakeholder community, and not the ICANN community.

The NTIA announcement DOES NOT prevent the possibility of removal of ICANN from its role as operator of IANA functions. While ICANN has tried to frame the Scoping Document in a language to prevent any discussions on its role as operator of IANA functions, the question whether ICANN should continue in its operator role remains an open one. There are at least 12 submissions made in response to ICANN’s Draft Proposal by varied stakeholders, which in fact, call for the separation of ICANN’s role as policy maker (through IETF, ASO, gNSO, ccNSO), and ICANN’s role as the operator of IANA functions. Such calls for separation come from private sector, civil society, as well as the technical community, among others. Such separation was also endorsed in the final NETmundial outcome document (paragraph 27). Governments have, in general, expressed no opinion on such separation in response to ICANN’s Draft Proposal. It is however urged that governments express their opinion in favour of such separation to prevent consolidation of both policy making and implementation within ICANN, which would lead to increased potential situations for the ICANN Board to abuse its powers.

Smarika Kumar is a graduate of the National Law Institute University, Bhopal, and a member of the Alternative Law Forum, a collective of lawyers aiming to integrate alternative lawyering with critical research, alternative dispute resolution, pedagogic interventions and sustained legal interventions in social issues. Her areas of interest include interdisciplinary research on the Internet, issues affecting indigenous peoples, eminent domain, traditional knowledge and pedagogy.

CIS Policy Brief: IANA Transition Fundamentals & Suggestions for Process Design

Short Introduction:

In March 2014, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) announced its intention to transition key Internet domain name functions to the global multi-stakeholder community. Currently, the NTIA oversees coordination and implementation of IANA functions through contractual arrangements with ICANN and Verisign, Inc.

The NTIA will not accept a government-led or inter-governmental organization to steward IANA functions. It requires the IANA transition proposal to have broad community support, and to be in line with the following principles: (1) support and enhance the multi-stakeholder model; (2) maintain the security, stability, and resiliency of the Internet DNS; (3) meet the needs and expectation of the global customers & partners of IANA services; (4) maintain the openness of the Internet.

ICANN was charged with developing a proposal for IANA transition. It initiated a call for public input in April 2014. Lamentably, the scoping document for the transition did not include questions of ICANN’s own accountability and interests in IANA stewardship, including whether it should continue to coordinate the IANA functions. Public Input received in May 2014 revolved around the composition of a Coordination Group, which would oversee IANA transition. Now, ICANN will hold an open session on June 26, 2014 at ICANN-50 to gather community feedback on issues relating to IANA transition, including composition of the Coordination Group.

CIS Policy Brief:

CIS' Brief on IANA Transition Fundamentals explains the process further, and throws light on the Indian government's views. To read the brief, please go here.

Suggestions for Process Design

As convenor of the IANA stewardship transition, ICANN has sought public comments on issues relating to the transition process. We suggest certain principles for open, inclusive and transparent process-design:

Short Introduction:

In March 2014, the US government through National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) announced its intention to transition key Internet domain name functions (IANA) to the global multi-stakeholder community. The NTIA announcement states that it will not accept a government-led or intergovernmental organization solution to replace its own oversight of IANA functions. The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) was charged with developing a Proposal for the transition.

At ICANN-49 in Singapore (March 2014), ICANN rapidly gathered inputs from its community to develop a draft proposal for IANA transition. It then issued a call for public input on the Draft Proposal in April 2014. Some responses were incorporated to create a Revised Proposal, published on June 6, 2014.

Responses had called for transparent composition of an IANA transition Coordination Group, a group comprising representatives of ICANN’s Advisory Committees and Supporting Organizations, as well as Internet governance organizations such as the IAB, IETF and ISOC. Also, ICANN was asked to have a neutral, facilitative role in IANA transition. This is because, as the current IANA functions operator, it has a vested interest in the transition. Tellingly, ICANN’s scoping document for IANA transition did not include questions of its own role as IANA functions operator.

ICANN is currently deliberating the process to develop a Proposal for IANA transition. At ICANN-50, ICANN will hold a governmental high-level meeting and a public discussion on IANA transition, where comments and concerns can be voiced. In addition, discussion in other Internet governance fora is encouraged.

CIS Policy Brief:

IANA Transition: Suggestions for Process Design

Introduction:

On 14 March 2014, the NTIA of the US Government announced its intention to transition key internet domain name functions to the global multistakeholder community. These key internet domain name functions comprise functions executed by Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA), which is currently contracted to ICANN by the US government. The US Government delineated that the IANA transition proposal must have broad community support and should address the following four principles:

- Support and enhance the multistakeholder model;

- Maintain the security, stability, and resiliency of the Internet DNS;

- Meet the needs and expectation of the global customers and partners of the IANA services; and

- Maintain the openness of the Internet.

Additionally, the US Government asked ICANN to convene a multistakeholder process to develop the transition plan for IANA. In April 2014, ICANN issued a Scoping Document for this process which outlined the scope of the process, as well as, what ICANN thinks, should not be a part of the process. In the spirit of ensuring broad community consensus, ICANN issued a Call for Public Input on the Draft Proposal of the Principles, Mechanisms and Process to Develop a Proposal to Transition NTIA’s Stewardship of IANA Functions on 8 April 2014, upon which the Government of India made its submission.

ICANN is currently deliberating the process for the development of a proposal for transition of IANA functions from the US Government to the global multistakeholder community, a step which would have implications for internet users all over the world, including India. The outcome of this process will be a proposal for IANA transition. The Scoping Document and process for development of the proposal are extremely limited and exclusionary, hurried, and works in ways which could potentially further ICANN’s own interests instead of global public interests. Accordingly, the Government of India is recommended take a stand on the following key points concerning the suggested process.

Submissions by the Government of India thus far, have however, failed to comment on the process being initiated by ICANN to develop a proposal for IANA transition. While the actual outcome of the process in form of a proposal for transition is an important issue for deliberation, we hold that it is of immediate importance that the Government of India, along with all governments of the world, pay particular attention to the way ICANN is conducting the process itself to develop the IANA transition proposal. The scrutiny of this process is of immense significance in order to ensure that democratic and representative principles sought by the GoI in internet governance are being upheld within the process of developing the IANA transition proposal. How the governance of the IANA functions will be structured will be an outcome of this process. Therefore if one expects a democratic, representative and transparent governance of IANA functions as the outcome, it is absolutely essential to ensure that the process itself is democratic, representative and transparent.

Issues and Recommendations:

Ensuring adequate representation and democracy of all stakeholders in the process for developing the proposal for IANA transition is essential to ensuring representative and democratic outcomes. Accordingly, one must take note of the following issues and recommendations concerning the process.

Open, inclusive deliberation by global stakeholders must define the Scope of the Process for developing proposal for IANA transition:

The current Scoping Document was issued by ICANN to outline the scope of the process by which the proposal for IANA transition would be deliberated. The Scoping Document was framed unilaterally by ICANN, without involvement of the global stakeholder community, and excluding all governments of the world including USA. Although this concern was voiced by a number of submissions to the Public Call by ICANN on the Draft Proposal, such concern was not reflected in ICANN’s Revised Proposal of 6 June 2014. It merely states that the Scoping Document outlines the “focus of this process.” Such a statement is not enough because the focus as well as the scope of the process needs to be decided in a democratic, unrepresentative and transparent manner by the global stakeholder community, including all governments.

This unilateral approach to outline which aspects of IANA transition should be allowed for discussion, and which aspects should not, itself defeats the multistakeholder principle which ICANN and the US government claim the process is based on. Additionally, global community consensus which the US Govt. hopes for the outcome of such process, cannot be conceivable when the scope of such process is decided in a unilateral and undemocratic manner. Accordingly, the current Scoping Document should be treated only as a draft, and should be made open to public comment and discussion by the global stakeholder community in order that the scope of the process reflects concerns of global stakeholders, and not just of the ICANN or the US Government.

Accountability of ICANN must be linked to IANA Transition within Scope of the Process:

ICANN Accountability must not run merely as a parallel process, since ICANN accountability has direct impact on IANA transition. The current Scoping Document states, “NTIA exercises no operational role in the performance of the IANA functions. Therefore, ICANN’s role as the operator of the IANA functions is not the focus of the transition: it is paramount to maintain the security, stability, and resiliency of the DNS, and uninterrupted service to the affected parties.” However this rationale to exclude ICANN’s role as operator of IANA from the scope of the process is not sound because NTIA does choose to appoint ICANN as the operator of IANA functions, thereby playing a vicarious operational role in the performance of IANA functions.

The explicit exclusion of ICANN’s role as operator of IANA functions from the scope of the process works to serve ICANN’s own interests by preventing discussions on those alternate models where ICANN does not play the operator role. Basically, this presumes that in absence of NTIA stewardship ICANN will control the IANA functions. Such presumption raises disturbing questions regarding ICANN’s accountability as the IANA functions operator. If discussions on ICANN’s role as operator of IANA functions is to be excluded from the process of developing the proposal for IANA transition, it also implies exclusion of discussions regarding ICANN’s accountability as operator of these functions.

Although ICANN announced a process to enhance its accountability on 6 May 2014, this was designed as a separate, parallel process and de-linked from the IANA transition process. As shown, ICANN’s accountability, its role as convenor of IANA transition process, and its role as current and/or potential future operator of IANA functions are intrinsically linked, and must not be discussed in separate, but parallel process. It is recommended that ICANN accountability in the absence of NTIA stewardship, and ICANN’s role as the operator of IANA functions must be included within the Scoping Document as part of the scope of the IANA transition process. This is to ensure that no kind of IANA transition is executed without ensuring ICANN’s accountability as and if as the operator of IANA functions so that democracy and transparency is brought to the governance of IANA functions.

Misuse or appearance of misuse of its convenor role by ICANN to influence outcome of the Process must not be allowed:

ICANN has been designated the convenor role by the US Govt. on basis of its unique position as the current IANA functions contractor and the global co-ordinator for the DNS. However it is this unique position itself which creates a potential for abuse of the process by ICANN. As the current contractor of IANA functions, ICANN has an interest in the outcome of the process being conducive to ICANN. In other words, ICANN prima facie is an interested party in the IANA transition process, which may tend to steer the process towards an outcome favourable to itself. ICANN has already been attempting to set the scope of the process to develop the proposal for IANA transition unilaterally, thus abusing its position as convenor. ICANN has also been trying to separate the discussions on IANA transition and its own accountability by running them as parallel processes, as well as attempting to prevent questions on ICANN’s role as operator of IANA functions by excluding it from the Scoping Document. Such instances provide a strong rationale for defining the limitations of the role of ICANN as convenor.

Although ICANN’s Revised Proposal of 6 June 2014 stating that ICANN will have a neutral role, and the Secretariat will be independent of ICANN staff is welcome, additional safeguards need to be put in place to avoid conflicts of interest or appearance of conflicts of interest. The Revised Proposal itself was unilaterally issued, whereby ICANN incorporated some of the comments made on its Proposed Draft, in the revised Draft, but excluded some others without providing rationale for the same. For instance, comments regarding inclusion of ICANN’s role as the operator of IANA functions within the Scoping Document, were ignored by ICANN in its Revised Proposal.

It is accordingly suggested that ICANN should limit its role to merely facilitating discussions and not extend it to reviewing or commenting on emerging proposals from the process. ICANN should further not compile comments on drafts to create a revised draft at any stage of the process. Additionally, ICANN staff must not be allowed to be a part of any group or committee which facilitates or co-ordinates the discussion regarding IANA transition.

Components of Diversity Principle should be clearly enunciated in the Draft Proposal:

The Diversity Principle was included by ICANN in the Revised Proposal of 6 June 2014 subsequent to submissions by various stakeholders who raised concerns regarding developing world participation, representation and lack of multilingualism in the process. This is laudable. However, past experience with ICANN processes has shown that many representatives from developing countries as well as from stakeholder communities outside of the ICANN community are unable to productively involve themselves in such processes because of lack of multilingualism or unfamiliarity with its way of functioning. This often results in undemocratic, unrepresentative and non-transparent decision-making in such processes.

In such a scenario, merely mentioning diversity as a principle is not adequate to ensure abundant participation by developing countries and non-ICANN community stakeholders in the process. Concrete mechanisms need to be devised to include adequate and fair geographical, gender, multilingual and developing countries’ participation and representation on all levels so that the process is not relegated merely to domination by North American or European entities. Accordingly, all the discussions in the process should be translated into multiple native languages of participants in situ, so that everyone participating in the process can understand what is going on. Adequate time must be given for the discussion issues to be translated and circulated widely amongst all stakeholders of the world, before a decision is taken or a proposal is framed. To concretise its diversity principle, ICANN should also set aside funds and develop a programme with community support for capacity building for stakeholders in developing nations to ensure their fruitful involvement in the process.

The Co-ordination Group must be made representative of the global multistakeholder community:

Currently, the Co-ordination Group includes representatives from ALAC, ASO, ccNSO, GNSO, gTLD registries, GAC, ICC/BASIS, IAB, IETF, ISOC, NRO, RSSAC and SSAC. Most of these representatives belong to the ICANN community, and is not representative of the global multistakeholder community including governments. This is not representative of even a multistakeholder model which the US Govt. has announced for the transition; nor in the multistakeholder participation spirit of NETmundial.

It is recommended that the Co-ordination Group then must be made democratic and representative to include larger global stakeholder community, including Governments, Civil Society, and Academia, with suitably diverse representation across geography, gender and developing nations. Adequate number of seats on the Committee must be granted to each stakeholder so that they can each co-ordinate discussions within their own communities and ensure wider and more inclusive participation.

Framing of the Proposal must allow adequate time:

All stakeholder communities must be permitted adequate time to discuss and develop consensus. Different stakeholder communities have different processes of engagement within their communities, and may take longer to reach a consensus than others. If democracy and inclusiveness are to be respected, then each stakeholder must be allowed enough time to reach a consensus within its own community, unlike the short time given to comment on the Draft Proposal. The process must not be rushed to benefit a few.

Smarika Kumar is a graduate of the National Law Institute University, Bhopal, and a member of the Alternative Law Forum, a collective of lawyers aiming to integrate alternative lawyering with critical research, alternative dispute resolution, pedagogic interventions and sustained legal interventions in social issues. Her areas of interest include interdisciplinary research on the Internet, issues affecting indigenous peoples, eminent domain, traditional knowledge and pedagogy.

IANA Transition Recommendatory Brief

*CIS - IANA Recommendatory Brief.pdf

—

PDF document,

497 kB (509647 bytes)

*CIS - IANA Recommendatory Brief.pdf

—

PDF document,

497 kB (509647 bytes)

FOEX Live: June 16-23, 2014

A quick and non-exhaustive perusal of this week’s content shows that many people are worried about the state of India’s free speech following police action on account of posts derogatory to or critical of the Prime Minister. Lawyers, journalists, former civil servants and other experts have joined in expressing this worry.

While a crackdown on freedom of expression would indeed be catastrophic and possibly unconstitutional, fears are so far based on police action in only 4 recent cases: Syed Waqar in Karnataka, Devu Chodankar in Goa and two cases in Kerala where college students and principals were arrested for derogatory references to Modi. Violence in Pune, such as the murder of a young Muslim man on his way home from prayer, or the creation of a Social Peace Force of citizens to police offensive Facebook content, are all related, but perhaps ought to be more carefully and deeply explored.

Kerala:

In the Assembly, State Home Minister Ramesh Chennithala said that the State government did not approve of the registration of cases against students on grounds of anti-Modi publications. The Minister denunciation of political opponents through cartoons and write-ups was common practice in Kerala, and “booking the authors for this was not the state government’s policy”.

Maharashtra:

Nearly 20,000 people have joined the Social Peace Force, a Facebook group that aims to police offensive content on the social networking site. The group owner’s stated aim is to target religious posts that may provoke riots, not political ones. Subjective determinations of what qualifies as ‘offensive content’ remain a troubling issue.

Tamil Nadu:

In Chennai, 101 people, including filmmakers, writers, civil servants and activists, have signed a petition requesting Chief Minister J. Jayalalithaa to permit safe screening of the Indo-Sri Lankan film “With You, Without You”. The petition comes after theatres cancelled shows of the film following threatening calls from some Tamil groups.

Telangana:

The K. Chandrasekhar Rao government has blocked two Telugu news channels for airing content that was “derogatory, highly objectionable and in bad taste”.

The Telagana government’s decision to block news channels has its supporters. Padmaja Shaw considers the mainstream Andhra media contemptuous and disrespectful of “all things Telangana”, while Madabushi Sridhar concludes that Telugu channel TV9’s coverage violates the dignity of the legislature.

West Bengal:

Seemingly anti-Modi arrests have led to worry among citizens about speaking freely on the Internet. Section 66A poses a particular threat.

News & Opinion:

The Department of Telecom is preparing a draft of the National Telecom Policy, in which it plans to treat broadband Internet as a basic right. The Policy, which will include deliberations on affordable broadband access for end users, will be finalised in 100 days.

While addressing a CII CEO’s Roundtable on Media and Industry, Information and Broadcasting Minister Prakash Javadekar promised a transparent and stable policy regime, operating on a time-bound basis. He promised that efforts would be streamlined to ensure speedy and transparent clearances.

A perceived increase in police action against anti-Modi publications or statements has many people worried. But the Prime Minister himself was once a fierce proponent of dissent; in protest against the then-UPA government’s blocking of webpages, Modi changed his display pic to black.

Medianama wonders whether the Mumbai police’s Cyber Lab and helpline to monitor offensive content on the Internet is actually a good idea.

G. Sampath wonders why critics of the Prime Minister Narendra Modi can’t voluntarily refrain from exercising their freedom of speech, and allow India to be an all-agreeable development haven. Readers may find his sarcasm subtle and hard to catch.

Experts in India mull over whether Section 79 of the Information Technology Act, 2000, carries a loophole enabling users to exercise a ‘right to be forgotten’. Some say Section 79 does not prohibit user requests to be forgotten, while others find it unsettling to provide private intermediaries such powers of censorship.

Some parts of the world:

Sri Lanka has banned public meetings or rallies intended to promote religious hatred.

In Pakistan, Twitter has restored accounts and tweets that were taken down last month on allegations of being blasphemous or ‘unethical’.

In Myanmar, an anti-hate speech network has been proposed throughout the country to raise awareness and opposition to hate speech and violence.

For feedback, comments and any incidents of online free speech violation you are troubled or intrigued by, please email Geetha at geetha[at]cis-india.org or on Twitter at @covertlight.

Free Speech and Civil Defamation

Previously on this blog, we have discussed one of the under-analysed aspects of Article 19(2) – contempt of court. In the last post, we discussed the checking – or “watchdog” – function of the press. There is yet another under-analysed part of 19(2) that we now turn to – one which directly implicates the press, in its role as public watchdog. This is the issue of defamation.

Unlike contempt of court – which was a last-minute insertion by Ambedkar, before the second reading of the draft Constitution in the Assembly – defamation was present in the restrictions clause since the Fundamental Rights Sub-Committee’s first draft, in 1947. Originally, it accompanied libel and slander, before the other two were dropped for the simpler “reasonable restrictions… in the interests of… defamation.” Unlike the other restrictions, which provoked substantial controversy, defamation did not provoke extended scrutiny by the Constituent Assembly.

In hindsight, that was a lapse. In recent years, defamation lawsuits have emerged as a powerful weapon against the press, used primarily by individuals and corporations in positions of power and authority, and invariably as a means of silencing criticism. For example, Hamish MacDonald’s The Polyester Prince, a book about the Ambanis, was unavailable in Indian bookshops, because of threats of defamation lawsuits. In January, Bloomsbury withdrew The Descent of Air India, which was highly critical of ex-Aviation Minister Praful Patel, after the latter filed a defamation lawsuit. Around the same time, Sahara initiated a 200 crore lawsuit against Tamal Bandyopadhayay, a journalist with The Mint, for his forthcoming book, Sahara: The Untold Story. Sahara even managed to get a stay order from a Calcutta High Court judge, who cited one paragraph from the book, and ruled that “Prima facie, the materials do seem to show the plaintiffs in poor light.” The issue has since been settled out of Court. Yet there is no guarantee that Bandyopadhyay would have won on merits, even with the absurd amount claimed as damages, given that a Pune Court awarded damages of Rs. 100 crores to former Justice P.B. Sawant against the Times Group, for a fifteen-second clip by a TV channel that accidentally showed his photograph next to the name of a judge who was an accused in a scam. What utterly takes the cake, though, is Infosys serving legal notices to three journalistic outlets recently, asking for damages worth Rs. 200 crore for “loss of reputation and goodwill due to circulation of defamatory articles.”

Something is very wrong here. The plaintiffs are invariably politicians or massive corporate houses, and the defendants are invariably journalists or newspapers. The subject is always critical reporting. The damages claimed (and occasionally, awarded) are astronomical – enough to cripple or destroy any business – and the actual harm is speculative. A combination of these factors, combined with a broken judicial system in which trials take an eternity to progress, leading to the prospect of a lawsuit hanging perpetually over one’s head, and financial ruin just around the corner, clearly has the potential to create a highly effective chilling effect upon newspapers, when it come to critical speech on matters of public interest.

One of the reasons that this happens, of course, is that extant defamation law allows it to happen. Under defamation law, as long as a statement is published, is defamatory (that is, tending to lower the reputation of the plaintiff in the minds of reasonable people) and refers to the plaintiff, a prima facie case of defamation is made out. The burden then shifts to the defendant to argue a justification, such as truth, or fair comment, or privileged communication. Notice that defamation, in this form, is a strict liability offence: that is, the publisher cannot save himself even if he has taken due care in researching and writing his story. Even an inadvertent factual error can result in liability. Furthermore, there are many things that straddle a very uncomfortable barrier between “fact” and “opinion” (“opinions” are generally not punishable for defamation): for example, if I call you “corrupt”, have I made a statement of fact, or one of opinion? Much of reporting – especially political reporting – falls within this slipstream.

The legal standard of defamation, therefore, puts almost all the burden upon the publisher, a burden that will often be impossible to discharge – as well as potentially penalising the smallest error. Given the difficulty in fact-checking just about everything, as well as the time pressures under which journalists operate, this is an unrealistic standard. What makes things even worse, however, is that there is no cap on damages, and that the plaintiff need not even demonstrate actual harm in making his claims. Judges have the discretion to award punitive damages, which are meant to serve both as an example and as a deterrent. When Infosys claims 2000 crores, therefore, it need not show that there has been a tangible drop in its sales, or that it has lost an important and lucrative contract – let alone showing that the loss was caused by the defamatory statement. All it needs to do is make abstract claims about loss of goodwill and reputation, which are inherently difficult to verify either way, and it stands a fair chance of winning.

A combination of onerous legal standards and crippling amounts in damages makes the defamation regime a very difficult one for journalists to operate freely in. We have discussed before the crucial role that journalists play in a system of free speech whose underlying foundation is the maintenance of democracy: a free press is essential to maintaining a check upon the actions of government and other powerful players, by subjecting them to scrutiny and critique, and ensuring that the public is aware of important facts that government might be keen to conceal. In chilling journalistic speech, therefore, defamation laws strike at the heart of Article 19(1)(a). When considering what the appropriate standards ought to be, a Court therefore must consider the simple fact that if defamation – as it stands today – is compromising the core of 19(1)(a) itself, then it is certainly not a “reasonable restriction” under 19(2) (some degree of proportionality is an important requirement for 19(2) reasonableness, as the Court has held many times).

This is not, however, a situation unique to India. In Singapore, for instance, “[political] leaders have won hundreds of thousands of dollars in damages in defamation cases against critics and foreign publications, which they have said are necessary to protect their reputations from unfounded attacks” – the defamation lawsuit, indeed, was reportedly a legal strategy used by Lee Kuan Yew against political opponents.

Particularly in the United States, the European Union and South Africa, however, this problem has been recognised, and acted upon. In the next post, we shall examine some of the legal techniques used in those jurisdictions, to counter the chilling effect that strict defamation laws can have on the press.

We discussed the use of civil defamation laws as weapons to stifle a free and critical press. One of the most notorious of such instances also birthed one of the most famous free speech cases in history: New York Times v. Sullivan. This was at the peak of the civil rights movement in the American South, which was accompanied by widespread violence and repression of protesters and civil rights activists. A full-page advertisement was taken out in the New York Times, titled Heed Their Rising Voices, which detailed some particularly reprehensible acts by the police in Montgomery, Alabama. It also contained some factual errors. For example, the advertisement mentioned that Martin Luther King Jr. had been arrested seven times, whereas he had only been arrested four times. It also stated that the Montgomery police had padlocked students into the university dining hall, in order to starve them into submission. That had not actually happened. On this basis, Sullivan, the Montgomery police commissioner, sued for libel. The Alabama courts awarded 500,000 dollars in damages. Because five other people in a situation similar to Sullivan were also suing, the total amount at stake was three million dollars – enough to potentially boycott the New York Times, and certainly enough to stop it from publishing about the civil rights movement.

In his book about the Sullivan case, Make No Law, Anthony Lewis notes that the stakes in the case were frighteningly high. The civil rights movement depended, for its success, upon stirring public opinion in the North. The press was just the vehicle to do it, reporting as it did on excessive police brutality against students and peaceful protesters, practices of racism and apartheid, and so on. Sullivan was a legal strategy to silence the press, and its weapon of choice was defamation law.

In a 9 – 0 decision, the Supreme Court found for the New York Times, and changed the face of free speech law (and, according to Lewis, saved the civil rights movement). Writing for the majority, Justice Brennan made the crucial point that in order to survive, free speech needed “breathing space” – that is, the space to make errors. Under defamation law, as it stood, “the pall of fear and timidity imposed upon those who would give voice to public criticism [is] an atmosphere in which the First Amendment freedoms cannot survive.” And under the burden of proving truth, “would-be critics of official conduct may be deterred from voicing their criticism, even though it is believed to be true and even though it is, in fact, true, because of doubt whether it can be proved in court or fear of the expense of having to do so. They tend to make only statements which "steer far wider of the unlawful zone." For these reasons, Justice Brennan laid down an “actual malice” test for defamation – that is, insofar as the statement in question concerned the conduct of a public official, it was actionable for defamation only if the publisher either knew it was false, or published it with “reckless disregard” for its veracity. After New York Times, this standard has expanded, and the press has never lost a defamation case.

There are some who argue that in its zeal to protect the press against defamation lawsuits by the powerful, the Sullivan court swung the opposite way. In granting the press a near-unqualified immunity to say whatever it wanted, it subordinated the legitimate interests of people to their reputation and their dignity to an intolerable degree, and ushered in a regime of media unaccountability. This is evidently what the South African courts felt. In Khulamo v. Holomisa, Justice O’Regan accepted that the common law of defamation would have to be altered so as to reflect the new South African Constitution’s guarantees of the freedom of speech. Much like Justice Brennan, she noted that “the media are important agents in ensuring that government is open, responsive and accountable to the people as the founding values of our Constitution require”, as well as the chilling effect in requiring journalists to prove the truth of everything they said. Nonetheless, she was not willing to go as far as the American Supreme Court did. Instead, she cited a previous decision by the Supreme Court of Appeals, and incorporated a “resonableness standard” into defamation law. That is, “if a publisher cannot establish the truth, or finds it disproportionately expensive or difficult to do so, the publisher may show that in all the circumstances the publication was reasonable. In determining whether publication was reasonable, a court will have regard to the individual’s interest in protecting his or her reputation in the context of the constitutional commitment to human dignity. It will also have regard to the individual’s interest in privacy. In that regard, there can be no doubt that persons in public office have a diminished right to privacy, though of course their right to dignity persists. It will also have regard to the crucial role played by the press in fostering a transparent and open democracy. The defence of reasonable publication avoids therefore a winner-takes-all result and establishes a proper balance between freedom of expression and the value of human dignity. Moreover, the defence of reasonable publication will encourage editors and journalists to act with due care and respect for the individual interest in human dignity prior to publishing defamatory material, without precluding them from publishing such material when it is reasonable to do so.”

The South African Constitutional Court thus adopts a middle path between the two opposite zero-sum games that are traditional defamation law, and American first amendment law. A similar effort was made in the United Kingdom – the birthplace of the common law of defamation – with the passage of the 2013 Defamation Act. Under English law, the plaintiff must now show that there is likely to be “serious harm” to his reputation, and there is also public interest exception.

While South Africa and the UK try to tackle the problem at the level of standards for defamation, the ECHR has taken another, equally interesting tack: by limiting the quantum of damages. In Tolstoy Milolasky v. United Kingdom, it found a 1.5 million pound damage award “disproportionately large”, and held that there was a violation of the ECHR’s free speech guarantee that could not be justified as necessary in a democratic society.

Thus, constitutional courts the world over have noticed the adverse impact traditional defamation law has on free speech and a free press. They have devised a multiplicity of ways to deal with this, some more speech-protective than others: from America’s absolutist standards, to South Africa’s “reasonableness” and the UK’s “public interest” exceptions, to the ECHR’s limitation of damages. It is about time that the Indian Courts took this issue seriously: there is no dearth of international guidance.

Gautam Bhatia — @gautambhatia88 on Twitter — is a graduate of the National Law School of India University (2011), and has just received an LLM from the Yale Law School. He blogs about the Indian Constitution at http://indconlawphil.wordpress.com. Here at CIS, he blogs on issues of online freedom of speech and expression.

An Evidence based Intermediary Liability Policy Framework: Workshop at IGF

The Centre for Internet and Society, India and Centre for Internet and Society, Stanford Law School, USA, will be organising a workshop to analyse the role of intermediary platforms in relation to freedom of expression, freedom of information and freedom of association at the Internet Governance Forum 2014. The aim of the workshop is to highlight the increasing importance of digital rights and broad legal protections of stakeholders in an increasingly knowledge-based economy. The workshop will discuss public policy issues associated with Internet intermediaries, in particular their roles, legal responsibilities and related liability limitations in context of the evolving nature and role of intermediaries in the Internet ecosystem. distinct

Online Intermediaries: Setting the context

The Internet has facilitated unprecedented access to information and amplified avenues for expression and engagement by removing the limits of geographic boundaries and enabling diverse sources of information and online communities to coexist. Against the backdrop of a broadening base of users, the role of intermediaries that enable economic, social and political interactions between users in a global networked communication is ubiquitous. Intermediaries are essential to the functioning of the Internet as many producers and consumers of content on the internet rely on the action of some third party–the so called intermediary. Such intermediation ranges from the mere provision of connectivity, to more advanced services such as providing online storage spaces for data, acting as platforms for storage and sharing of user generated content (UGC), or platforms that provides links to other internet content.

Online intermediaries enhance economic activity by reducing costs, inducing competition by lowering the barriers for participation in the knowledge economy and fuelling innovation through their contribution to the wider ICT sector as well as through their key role in operating and maintaining Internet infrastructure to meet the network capacity demands of new applications and of an expanding base of users.

Intermediary platforms also provide social benefits, by empowering users and improving choice through social and participative networks, or web services that enable creativity and collaboration amongst individuals. By enabling platforms for self-expression and cooperation, intermediaries also play a critical role in establishing digital trust, protection of human rights such as freedom of speech and expression, privacy and upholding fundamental values such as freedom and democracy.

However, the economic and social benefits of online intermediaries are conditional to a framework for protection of intermediaries against legal liability for the communication and distribution of content which they enable.

Intermediary Liability

Over the last decade, right holders, service providers and Internet users have been locked in a debate on the potential liability of online intermediaries. The debate has raised global concerns on issues such as, the extent to which Internet intermediaries should be held responsible for content produced by third parties using their Internet infrastructure and how the resultant liability would affect online innovation and the free flow of knowledge in the information economy?

Given the impact of their services on communications, intermediaries find themselves as either directly liable for their actions, or indirectly (or “secondarily”) liable for the actions of their users. Requiring intermediaries to monitor the legality of the online content poses an insurmountable task. Even if monitoring the legality of content by intermediaries against all applicable legislations were possible, the costs of doing so would be prohibitively high. Therefore, placing liability on intermediaries can deter their willingness and ability to provide services, hindering the development of the internet itself.

Economics of intermediaries are dependent on scale and evaluating the legality of an individual post exceeds the profit from hosting the speech, and in the absence of judicial oversight can lead to a private censorship regime. Intermediaries that are liable for content or face legal exposure, have powerful incentives, to police content and limit user activity to protect themselves. The result is curtailing of legitimate expression especially where obligations related to and definition of illegal content is vague. Content policing mandates impose significant compliance costs limiting the innovation and competiveness of such platforms.

More importantly, placing liability on intermediaries has a chilling effect on freedom of expression online. Gate keeping obligations by service providers threaten democratic participation and expression of views online, limiting the potential of individuals and restricting freedoms. Imposing liability can also indirectly lead to the death of anonymity and pseudonymity, pervasive surveillance of users' activities, extensive collection of users' data and ultimately would undermine the digital trust between stakeholders.

Thus effectively, imposing liability for intermediaries creates a chilling effect on Internet activity and speech, create new barriers to innovation and stifles the Internet's potential to promote broader economic and social gains. To avoid these issues, legislators have defined 'safe harbours', limiting the liability of intermediaries under specific circumstances.

Online intermediaries do not have direct control of what information is or information are exchanged via their platform and might not be aware of illegal content per se. A key framework for online intermediaries, such limited liability regimes provide exceptions for third party intermediaries from liability rules to address this asymmetry of information that exists between content producers and intermediaries.

However, it is important to note, that significant differences exist concerning the subjects of these limitations, their scope of provisions and procedures and modes of operation. The 'notice and takedown' procedures are at the heart of the safe harbour model and can be subdivided into two approaches:

a. Vertical approach where liability regime applies to specific types of content exemplified in the US Digital Copyright Millennium Act

b. Horizontal approach based on the E-Commerce Directive (ECD) where different levels of immunity are granted depending on the type of activity at issue

Current framework

Globally, three broad but distinct models of liability for intermediaries have emerged within the Internet ecosystem:

1. Strict liability model under which intermediaries are liable for third party content used in countries such as China and Thailand

2. Safe harbour model granting intermediaries immunity, provided their compliance on certain requirements

3. Broad immunity model that grants intermediaries broad or conditional immunity from liability for third party content and exempts them from any general requirement to monitor content.

While the models described above can provide useful guidance for the drafting or the improvement of the current legislation, they are limited in their scope and application as they fail to account for the different roles and functions of intermediaries. Legislators and courts are facing increasing difficulties, in interpreting these regulations and adapting them to a new economic and technical landscape that involves unprecedented levels user generated content and new kinds of and online intermediaries.

The nature and role of intermediaries change considerably across jurisdictions, and in relation to the social, economic and technical contexts. In addition to the dynamic nature of intermediaries the different categories of Internet intermediaries‘ are frequently not clear-cut, with actors often playing more than one intermediation role. Several of these intermediaries offer a variety of products and services and may have number of roles, and conversely, several of these intermediaries perform the same function. For example , blogs, video services and social media platforms are considered to be 'hosts'. Search engine providers have been treated as 'hosts' and 'technical providers'.

This limitations of existing models in recognising that different types of intermediaries perform different functions or roles and therefore should have different liability, poses an interesting area for research and global deliberation. Establishing classification of intermediaries, will also help analyse existing patterns of influence in relation to content for example when the removal of content by upstream intermediaries results in undue over-blocking.

Distinguishing intermediaries on the basis of their roles and functions in the Internet ecosystem is critical to ensuring a balanced system of liability and addressing concerns for freedom of expression. Rather than the highly abstracted view of intermediaries as providing a single unified service of connecting third parties, the definition of intermediaries must expand to include the specific role and function they have in relation to users' rights. A successful intermediary liability regime must balance the needs of producers, consumers, affected parties and law enforcement, address the risk of abuses for political or commercial purposes, safeguard human rights and contribute to the evolution of uniform principles and safeguards.

Towards an evidence based intermediary liability policy framework

This workshop aims to bring together leading representatives from a broad spectrum of stakeholder groups to discuss liability related issues and ways to enhance Internet users’ trust.

Questions to address at the panel include:

1. What are the varying definitions of intermediaries across jurisdictions?

2. What are the specific roles and functions that allow for classification of intermediaries?

3. How can we ensure the legal framework keeps pace with technological advances and the changing roles of intermediaries?

4. What are the gaps in existing models in balancing innovation, economic growth and human rights?

5. What could be the respective role of law and industry self-regulation in enhancing trust?

6. How can we enhance multi-stakeholder cooperation in this space?

Confirmed Panel:

Technical Community: Malcolm Hutty: Internet Service Providers Association (ISPA)

Civil Society: Gabrielle Guillemin: Article19

Academic: Nicolo Zingales: Assistant Professor of Law at Tilburg University

Intergovernmental: Rebecca Mackinnon: Consent of the Networked, UNESCO project

Civil Society: Anriette Esterhuysen: Association for Progressive Communication (APC)

Civil Society: Francisco Vera: Advocacy Director: Derechos Digitale

Private Sector: Titi Akinsanmi: Policy and Government Relations Manager, Google Sub-Saharan Africa

Legal: Martin Husovec: MaxPlanck Institute

Moderator(s): Giancarlo Frosio, Centre for Internet and Society (CIS) and Jeremy Malcolm, Electronic Frontier Foundation

Remote Moderator: Anubha Sinha, New Delhi

TLD

Full-size image: 230.6 KB |

ICANN’s Documentary Information Disclosure Policy – I: DIDP Basics

The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (“ICANN”) is a non-profit corporation incorporated in the state of California and vested with the responsibility of managing the DNS root, generic and country-code Top Level Domain name system, allocation of IP addresses and assignment of protocol identifiers. As an internationally organized corporation with its own multi-stakeholder community of Advisory Groups and Supporting Organisations, ICANN is a large and intricately woven governance structure. Necessarily, ICANN undertakes through its Bye-laws that “in performing its functions ICANN shall remain accountable to the Internet community through mechanisms that enhance ICANN’s effectiveness”. While many of its documents, such as its Annual Reports, financial statements and minutes of Board meetings, are public, ICANN has instituted the Documentary Information Disclosure Policy (“DIDP”), which like the RTI in India, is a mechanism through which public is granted access to documents with ICANN which are not otherwise available publicly. It is this policy – the DIDP – that I propose to study.

In a series of blogposts, I propose to introduce the DIDP to unfamiliar ears, and to analyse it against certain freedom of information best practices. Further, I will analyse ICANN’s responsiveness to DIDP requests to test the effectiveness of the policy. However, before I undertake such analysis, it is first good to know what the DIDP is, and how it is crucial to ICANN’s present and future accountability.

What is the DIDP?

One of the core values of the organization as enshrined under Article I Section 4.10 of the Bye-laws note that “in performing its functions ICANN shall remain accountable to the Internet community through mechanisms that enhance ICANN’s effectiveness”. Further, Article III of the ICANN Bye-laws, which sets out the transparency standard required to be maintained by the organization in the preliminary, states - “ICANN and its constituent bodies shall operate to the maximum extent feasible in an open and transparent manner and consistent with procedures designed to ensure fairness”.

Accordingly, ICANN is under an obligation to maintain a publicly accessible website with information relating to its Board meetings, pending policy matters, agendas, budget, annual audit report and other related matters. It is also required to maintain on its website, information about the availability of accountability mechanisms, including reconsideration, independent review, and Ombudsman activities, as well as information about the outcome of specific requests and complaints invoking these mechanisms.

Pursuant to Article III of the ICANN Bye-laws for Transparency, ICANN also adopted the DIDP for disclosure of publicly unavailable documents and publish them over the Internet. This becomes essential in order to safeguard the effectiveness of its international multi-stakeholder operating model and its accountability towards the Internet community. Thereby, upon request made by members of the public, ICANN undertakes to furnish documents that are in possession, custody or control of ICANN and which are not otherwise publicly available, provided it does not fall under any of the defined conditions for non-disclosure. Such information can be requested via an email to [email protected].

Procedure

- Upon the receipt of a DIDP request, it is reviewed by the ICANN staff.

- Relevant documents are identified and interview of the appropriate staff members is conducted.

- The documents so identified are then assessed whether they come under the ambit of the conditions for non-disclosure.

- Yes - A review is conducted as to whether, under the particular circumstances, the public interest in disclosing the documentary information outweighs the harm that may be caused by such disclosure.

- Documents which are considered as responsive and appropriate for public disclosure are posted on the ICANN website.

- In case of request of documents whose publication is appropriate but premature at the time of response then the same is indicated in the response and upon publication thereafter, is notified to the requester.

Time Period and Publication

The response to the DIDP request is prepared by the staff and is made available to the requestor within a period of 30 days of receipt of request via email. The Request and the Response is also posted on the DIDP page http://www.icann.org/en/about/transparency in accordance with the posting guidelines set forth at http://www.icann.org/en/about/transparency/didp.

Conditions for Non-Disclosure

There are certain circumstances under which ICANN may refuse to provide the documents requested by the public. The conditions so identified by ICANN have been categorized under 12 heads and includes internal information, third-party contracts, non-disclosure agreements, drafts of all reports, documents, etc., confidential business information, trade secrets, information protected under attorney-client privilege or any other such privilege, information which relates to the security and stability of the internet, etc.

Moreover, ICANN may refuse to provide information which is not designated under the specified conditions for non-disclosure if in its opinion the harm in disclosing the information outweighs the public interest in disclosing the information. Further, requests for information already available publicly and to create or compile summaries of any documented information may be declined by ICANN.

Grievance Redressal Mechanism

In certain circumstances the requestor might be aggrieved by the response received and so he has a right to appeal any decision of denial of information by ICANN through the Reconsideration Request procedure or the Independent Review procedure established under Section 2 and 3 of Article IV of the ICANN Bye-laws respectively. The application for review is made to the Board which has designated a Board Governance Committee for such reconsideration. The Independent Review is done by an independent third-party of Board actions, which are allegedly inconsistent with the Articles of Incorporation or Bye-laws of ICANN.

Why does the DIDP matter?

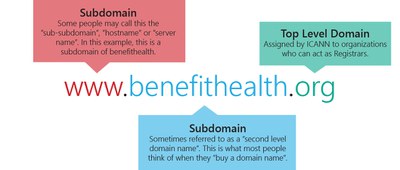

The breadth of ICANN’s work and its intimate relationship to the continued functioning of the Internet must be appreciated before our analysis of the DIDP can be of help. ICANN manages registration and operations of generic and country-code Top Level Domains (TLD) in the world. This is a TLD:

(Source: here)

Operation of many gTLDs, such as .com, .biz or .info, is under contract with ICANN and an entity to which such operation is delegated. For instance, Verisign operates the .com Registry. Any organization that wishes to allow others to register new domain names under a gTLD (sub-domains such as ‘benefithealth’ in the above example) must apply to ICANN to be an ICANN-accredited Registrar. GoDaddy, for instance, is one such ICANN-accredited Registrar. Someone like you or me, who wants to get our own website – say, vinayak.com – buys from GoDaddy, which has a contract with ICANN under which it pays periodic sums for registration and renewal of individual domain names. When I buy from an ICANN-accredited Registrar, the Registrar informs the Registry Operator (say, Verisign), who then adds the new domain name (vinayak.com) to its registry list, and then it can be accessed on the Internet.

ICANN’s reach doesn’t stop here, technically. To add a new gTLD, an entity has to apply to ICANN, after which the gTLD has to be added to the root file of the Internet. The root file, which has the list of all TLDs (or all ‘legitimate’ TLDs, some would say), is amended by Verisign under its tripartite contract with the US Government and ICANN, after which Verisign updates the file in its ‘A’ root server. The other 12 root servers use the same root file as the Verisign root server. Effectively, this means that only ICANN-approved TLDs (and all sub-domains such as ‘benefithealth’ or ‘vinayak’) are available across the Internet, on a global scale. Or at least, ICANN-approved TLDs have the most and widest reach. ICANN similarly manages country-code TLDs, such as .in for India, .pk for Pakistan or .uk for the United Kingdom.

All of this leads us to wonder whether the extent of ICANN’s voluntary and reactive transparency is sufficient for an organization of such scale and impact on the Internet, perhaps as much impact as the governments do. In the next post, I will analyse the DIDP’s conditions for non-disclosure of information with certain freedom of information best practices.

Vinayak Mithal is a final year student at the Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, Punjab. His interests lie in Internet governance and other aspects of tech law, which he hopes to explore during his internship at CIS and beyond. He may be reached at [email protected].

PMA Policy and COAI Recommendations

Introduction

The Ministry of Communications and Information Technology on the 10th of February, 2012 released a notification [1] in the Official Gazette outlining the Preferential Market Access [2] Policy for Domestically Manufactured Electronic Goods 2012. The Policy is applicable to procurement of telecom products by Government Ministries/Departments and to such electronics that had been deemed to having security concerns, thus making the policy applicable to private bodies in the latter half. The Notification reasoned that preferential access was to be given to domestically manufactured electronic goods predominantly for security reasons. Each Ministry or Department was to notify the products that had security implications, with reasons, after which the notified agencies would be required to procure the same from domestic manufacturers. This policy was also meant to be applicable to even procurement of electronic goods by Government Ministries/Agencies for Governmental purposes except Defence. Each Ministry would be required to notify its own percentage of such procurement, though it could not be less than 30%, and also had to specify the Value Addition that had to be made to a particular product to qualify it as a domestically manufactured product, with the policy again specifying the minimum standards. The policy was also meant for procurement of electronic hardware as a service from Managed Service Providers (MSPs).

The procurement was to be done as according to the policies of the each procuring agency. The tender was to be apportioned according to the procurement percentage notified and the preference part was to be allotted to the domestic manufacturer at the lowest bid price. If there were no bidders who were domestic manufacturers or if the tender was not severable, then it was to be awarded to the Foreign Manufacturer and the percentage adjusted as against other electronic procurement for that period.

Telecom equipment that qualifies as domestically manufactured telecom products for preferential market access include: encryption and UTM platforms, Core/Edge/Enterprise routers, Managed leased line network equipment, Ethernet Switches, IP based Soft Switches, Media gateways, Wireless/Wireline PABXs, CPE, 2G/3G Modems, Leased-line Modems, Set Top Boxes, SDH/Carrier Ethernet/Packet Optical Transport Eqiupments, DWDN systems, GPON equipments, Digital Cross connects, small size 2G/3G GSM based Base Station Systems, LTE based broadband wireless access systems, Wi-Fi based broadband wireless access systems, microwave radio systems, software defined radio cognitive radio systems, repeaters, IBS, and distributed antenna system, satellite based systems, copper access systems, network management systems, security and surveillance communication systems (video and sensors based), optical fiber cable.

The Policy also mentioned the creation of a self-certification system to declare domestic value addition to the vendor. The checks would be done by the laboratories accredited by the Department of Information Technology. The policy was to be in force for a period of 10 years and any dispute concerning the nature of product was to be referred to the Department of Information Technology.

International and Domestic Response to the Policy

There was a large scale opposition, usually from international sectors, towards the mooting of this policy. Besides business houses, even organizations like those of the United States Trades Representatives criticized the policy as being harmful to the global market and in violation of the World Trade Organization Guidelines.[3] Criticism also poured in from domestic bodies in terms of recommendations towards modification of the policy largely on three grounds: (i) the high domestic value addition requirement and the method of calculation of the same, (ii) the lack of a link between manufacturing and security and (iii) application of the policy to the private sector.

The Cellular Operations Association of India (COAI) in a letter dated March 15, 2012 to the Secretary of the Department Technology and Chairman of the Telecom Commission expressed its views on the telecom manufacturing in the country.[4]The COAI stated that such a development had to be done realistically and holistically so that the whole eco-system was developed as a comprehensive whole. In that regard it also forwarded a study that had been commissioned by COAI and conducted by M/s. Booz and Company titled “Telecom Manufacturing Policy – Developing an Actionable Roadmap”. The report was a comprehensive study of the telecom industry and outlined the challenges and opportunities that lay on its development trajectory. It also talked about Government involvement in the development process. The Report while citing the market share of Indian Telecom Industry which would be around 3% [5] of the Global Market highlighted the fact that no country could be self-sufficient in technology. It further talked about the development of local clusters in order to cut costs and encourage manufacturing, while ensuring that the PMA Policy was consistent with the WTO Guidelines. It further recommended opening up of foreign investments and making capital available to ensure growth of innovation. Finally it highlighted the lack of a connection between manufacturing and security and instead stressed upon proper certification, checks and development of a comprehensive CIIP framework across all sensitive networks for security purposes.

In a further letter to the Joint Secretary of the Department of Information and Technology dated April 25, 2012 the COAI expressed some reservations concerning the draft guidelines that had been published along with the notification.[6] While stressing upon the fact that a higher value addition would be impossible with the lack of basic manufacturing capabilities for the development of technological units, it also highlighted the need to redefine Bill of Materials which had been left ambiguous and subject to exploitation. It further highlighted the fact that allowing every Ministry to make its own specifications would lead to inconsistent definitions and an administrative challenge and hence such matters should be handled by a Central Body. Furthermore it opined that the calculation of BOMs and the Value Additions should be done using the concept of substantial transformation as has been given in the Booz Study. Furthermore, while discouraging the use of disincentives, it stated that one individual Ministry should be in charge of specifying such incentives to avoid confusion and for the sake of ease of business.

In another letter to a Member of the Department of Telecommunications dated July 12, 2012 the COAI stressed upon the futility of having high value additions as the same was impossible under the present scenario.[7] There was a lack of manufacturing sector which had to be comprehensively developed backed by fiscal incentives and comprehensive policies. In spite of that, it stressed that no country could become self-reliant and that such policies, like the PMA, were reminiscent of the “license and permit raj” era. It further said that such policies should be consistent with WTO Guidelines and should not give undue preference to domestic manufacturers to the detriment of other manufacturers. Countering the security aspect, it said that the same had been addressed by the DoT License Amendment of May 31, 2011 whereby all equipments on the network would have to comply with the “Safe to Connect” standard, and stressed upon the lack of any link between manufacturing and security. Furthermore for calculation of Value Addition it suggested an alternative to the method proposed by the Government as the same would lead to disclosures of sensitive commercial information which were contained in the BOMs. The COAI said that the three stages as laid out in the Substantial Transformation (as mentioned in the Booz Study) should be used for calculating the VA. It made several proposals to develop the telecom manufacturing industry in India including provision of fiscal incentives, development of telecom clusters and comprehensive policies which led to harmonization with laws and creation of SEZs among other such benefits.

In October 2012 the Government released a draft notification notifying products due to security consideration in furtherance of the PMA Policy.[8] The document outlined the minimum PMA and VA specification for a range of products. It also stated several security reasons for pursuing such a policy and stated that India had to be completely self-reliant for its active telecom products. It also contained data on the predicted growth of the telecom market in India. The COAI thereafter released a document commenting upon the draft notification of the Government.[9]

Besides highlighting the fact that the COAI still had not received a response to its former comments, it again stressed upon the lack of a link between security and manufacturing. It reiterated its point on the impossibility of a complete self-reliance on any nation’s part, and stressed upon the need of involving other stakeholders in the promulgation of such policies. It also made changes to the notified list of equipments, reclassifying it according to technology and only listing equipments which had volumes. Furthermore it also suggested changes towards the calculation of value addition to include materials sourced from local suppliers, in-house assemblage to be considered local material and the calculation to be done for complete order and not for each item in the order. It further recommended a study be conducted and the industry be involved while predicting demands as such were dated and needed revision. The Government thereafter released a revised notification[10] on October 5, 2012 but it did not contain much of the commented changes that the COAI had proposed.

Thereafter in April 2013, the DeitY released draft guidelines[11] for providing preference to domestically manufactured electronic products in Government Procurement in further of the second part of the PMA Policy. The guidelines besides containing definitions to several terms such as BOM also prescribed a minimum of 20% domestic procurement while leaving the specifications onto individual Ministries. It recommended the establishment of a technical committee by the concerned Ministry or Department that would recommend value addition to products. It followed a BOM based calculation of Value Addition while leaving the matter of certification to be dealt by DeitY certified laboratories that are notified for such purposes by the concerned Ministry/Department. DeitY was the nodal ministry for monitoring the implementation of the policy while particular monitoring was left to each Ministry or Department concerned. Among the annexures were indicative lists of generic and telecom products and a format for Self Certification regarding Domestic Value Addition in an Electronic Product.

The COAI thereafter released a revised draft containing its own comments on April 15, 2013.[12] The COAI pointed out faults in the definition of BOM. It highlighted the difficulty in splitting R&D according to countries, and also stressed upon the impractical usage of BOM in calculation of value addition as the same was confidential business information. As it had already suggested earlier, it reiterated the usage of the Substantial Transformation process for the calculation of Value Addition. While removing the lists of equipments mentioned, it further pointed out that the disqualification in the format for self-certification would be a very harsh disincentive and would result in driving away manufacturers. It suggested that there should be incentives for compliance instead.