Blog

Programme Booklet

Programme Booklet_small res-1.pdf

—

PDF document,

1473 kB (1508988 bytes)

Programme Booklet_small res-1.pdf

—

PDF document,

1473 kB (1508988 bytes)

CV Booklet

CV Booklet_small res-1.pdf

—

PDF document,

1796 kB (1840125 bytes)

CV Booklet_small res-1.pdf

—

PDF document,

1796 kB (1840125 bytes)

Consilience 2013 Report

Consilience 2013- Recommendatory Report and Conference Proceedings.pdf

—

PDF document,

915 kB (937019 bytes)

Consilience 2013- Recommendatory Report and Conference Proceedings.pdf

—

PDF document,

915 kB (937019 bytes)

CIS Supports the UN Resolution on “The Right to Privacy in the Digital age”.

On November 26, 2013, the United Nations adopted a non-binding resolution on The Right to Privacy in the Digital Age. The resolution was drafted by Brazil and Germany and expressed concern over the negative impact of surveillance and interception on the exercise of human rights. The resolution was controversial as countries such as the US, the UK, and Canada opposed language that spoke to the right to privacy extending equally to citizens and non-citizens of a country. The resolution welcomed the report of the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression that examined the implications of surveillance of communications on the human rights of privacy and freedom of expression.

The resolution made a number of important statements that India, as a member of the United Nations, and as a country in the process of implementing a number of surveillance projects, like the Central Monitoring System, should take cognizance of, including in short:

- Privacy is a human right: Privacy is a human right according to which no one should be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his or her privacy, family, home, or correspondence.

- Privacy is integral to the right to free expression: an integral component in recognizing the right to freedom of expression.

- Unlawful and arbitrary surveillance violates the right to privacy and freedom of expression: Unlawful and/or arbitrary surveillance, interception, and collection of personal data are intrusive acts that violate the right to privacy and freedom of expression.

- Exceptions to privacy and freedom of expression should be in compliance with human rights law: Public security is a potential exception justifying collection and protection of information, but States must ensure that this is done fully in compliance with international human rights law.

- Mass surveillance may have negative implications for human rights: Domestic and extraterritorial surveillance, interception, and the collection of personal data on a mass scale may have a negative impact on individual human rights.

- Equal protection for online and offline privacy: The right to privacy must be equally protected online and offline.

The resolution further called upon states to:

- Respect and protect the right to privacy, particularly in the context of digital communications.

- To ensure that relevant legislation is in compliance with international human rights law

- To review national procedures and practices around surveillance to ensure full and effective implementation of obligations under international human rights law.

- To establish and maintain effective domestic oversight mechanisms around domestic surveillance capable of ensuring transparency and accountability.

The resolution finally calls upon the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to present a report with views and recommendations on the protection and promotion of the right to privacy in the context of surveillance to the Human Rights Council at its twenty-seventh session and to the General Assembly at its sixty-ninth session and decides to examine “Human rights questions, including alternative approaches for improving the effective enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms”.

The UN Resolution on the Right to Privacy in the Digital Age is a welcome step towards an international recognition of privacy as a human right in the context of communications and extra territorial surveillance. The Centre for Internet and Society encourages the Government of India to, as called upon in the Resolution, to review national procedures and practices around surveillance to ensure full and effective implementation of obligations under international human rights law.

Prior to the UN Resolution on “The Right to Privacy in the Digital Age”, a group of international NGO’s developed the Necessary and Proportionate principles that seek to form a backbone for a response to mass surveillance and provide a framework for governments to assess if domestic surveillance regimes are in compliance with international Human Rights Law. CIS has contributed to the process of developing these principles. The principles include legality, legitimate aim, necessity, adequacy, proportionality, competent judicial authority, due process, user notification, transparency, public oversight, integrity of communications and systems, safeguards for international cooperation, and safeguards against illegitimate access. A petition to sign onto the principles and demand an end to mass surveillance is currently underway.

Both the Government of India and public of India should take into consideration the UN Resolution and the necessary and proportionate principles to reflect on how India’s surveillance regime and practices can be brought in line with international human rights law and understand where the balance is drawn for necessary and proportionate surveillance, specific to the Indian context.

Open Secrets

Dr. Nishant Shah's article was originally published in the Indian Express on October 27.

If you are a part of any social networking site, then you know that privacy is something to be concerned about. We put out an incredible amount of personal data on our social networks. Pictures with family and friends, intimate details about our ongoing drama with the people around us, medical histories, and our spur-of-the-moment thoughts of what inspires, peeves or aggravates us. In all this, the more savvy use filters and group settings which give them some semblance of control about who has access to this information and what can be done with it.

But it is now a given that in the world of the worldwide web, privacy is more or less a thing of the past. Data transmits. Information flows. What you share with one person immediately gets shared with thousands. Even though you might make your stuff accessible to a handful of people, the social networks work through a "friend-of-a-friend effect", where others in your networks use, like, share and spread your information around so that there is an almost unimaginable audience to the private drama of our lives. Which is why there is a need for a growing conversation about what being private in the world of big data means.

Privacy is about having control over the data and some ownership about who can use it and for what purpose. Interface designs and filters that allow limited access help this process. The legal structures are catching up with regulations that control what individuals, entities, governments and corporations can do with the data we provide. However, most people think of privacy as a private matter. Just look at last month's conversations around Facebook's new privacy policies, which no longer allow you to hide. If you are on Facebook, people can find you using all kinds of parameters — meta data — other than just your name. They might find you through hobbies, pages you like, schools you have studied in, etc. This can be scary because it means that based on particular activities, people can profile and follow you. Especially for people in precarious communities — the young adults, queer people who might not be ready to be out of the closet, women who already face increased misogyny and hostility online. This means they are officially entering a stalkers' paradise.

While those concerns need to be addressed, there is something that seems to be missing from the debate. Almost all of these privacy alarms are about what people can do to people. That we need to protect ourselves from people, when we are in public — digital or otherwise. We are reminded that the world is filled with predators, crackers and scamsters, who can prey on our personal data and create physical, emotional, social and financial havoc. But this is the world we already know. We live in a universe filled with perils and we have learned and coped with the fact that we navigate through dangerous spaces, times and people all the time. The digital is no different than the physical when it comes to the possible perils that we live in, though digital might facilitate some kinds of behaviour and make data-stalking easier.

What is different with the individualised, just-for-you crafted world of the social web is that there are things which are not human, which are interacting with you in unprecedented ways. Make a list of the top five people you interact with on Facebook. And you will be wrong. Because the thing that you interact with the most on Facebook, is Facebook. Look at the amount of chatter it creates — How are you feeling today?; Your friend has updated their status; Somebody liked your comment… the list goes on. In fact, much as we would like to imagine a world that revolves around us, we know that there are a very few people who have the energy and resources to keep track of everything we do. However, no matter how boring your status message or how pedestrian your activity, deep down in a server somewhere, an artificial algorithm is keeping track of everything that you do. Facebook is always listening, and watching, and creating a profile of you. People might forget, skip, miss or move on, but Facebook will listen, and remember long after you have forgotten.

If this is indeed the case, we need to think of privacy in different ways — not only as something that happens between people, but between people and other entities like corporations. The next time there is a change in the policy that makes us more accessible to others, we should pay attention. But what we need to be more concerned about are the private corporations, data miners and information gatherers, who make themselves invisible and collect our personal data as we get into the habit of talking to platforms, gadgets and technologies.

I Just Pinged to Say Hello

Dr. Nishant Shah's article was published in the Indian Express on November 24, 2013.

I am making a list of all the platforms that I use to connect with the large networks that I belong to. Here goes: I use Yahoo! Messenger to talk to my friends in east Asia. Most of my work meetings happen on Skype and Google Hangout. A lot of friendly chatter fills up my Facebook Messenger. Twitter is always available for a little back-chat and bitching. On the phone, I use Viber to make VoIP calls and WhatsApp is the space for unending conversations spread across days. And these are just the spaces for real-time conversation. Across all these platforms, something strange is happening. As I stay connected all the time, I am facing a phenomenon where we have run out of things to say, but not the desire to talk.

I had these three conversations today on three different instant-messaging platforms:

Person 1 (on WhatsApp): Hi.

Me: Hey, good to hear from you. How are you doing?

Person 1: Good.

Me (after considerable silence): So what's up?

Person 1: Nothing.

End of conversation.

Person 2 (On an incoming video call on Skype): Hey, you there?

Me: Yeah. What time is it for you right now?

Person 2: It is 10 at night.

Me: Oh! That is late. How come you are calling me so late?

Person 2: Oh, I saw you online.

Me: Ok….. *eyes raised in question mark*

Person 2: So, that's it. I am going to sleep soon.

Me: Ok…. Er…goodnight.

Person2: Goodnight.

We hang up.

Person 3 (pinging me on Facebook): Hey, you are in the US right now?

Me: Yes. I am attending a conference here.

Person 3: Cool!

Me: Umm… yeah, it is.

Person 3: emoticon of a Facebook 'like'. Have fun. Bye.

Initially I was irritated at the futility of these pings that are bewildering in their lack of content. I dismissed it as one of those things, but I realise that there is a pattern here. Our lives are so particularly open and documented, such minute details of what we do, where we are and who we are with, is now available for the rest of the world to consume, making most of the conversations seeking information, redundant. If you know me on my social media networks, you already know most of the basic things that you would want to know about me. And it goes without saying that no matter how close and connected we are, we are not necessarily in a state where we want to talk all the time. The more distributed our lives are, the more diminished is the need for personal communication.

And yet, the habit or the urge to ping, buzz, DM or chat has not caught up with this interaction deficit. So, we still seem to reach out, using a variety of platforms just to say hello, even when there is nothing to say. I call this the 'Always On' syndrome. We live in a world where being online all the time has become a ubiquitous reality. Even when we are asleep, or busy in a meeting, or just mentally disconnected from the online spaces, our avatars are still awake. They interact with others. And when they feel too lonely, they reach out and send that empty ping — just to confirm that they are not alone. That on the other side of the glowing screen is somebody else who is going to connect back, and to reassure you that we are all together in this state of being alone.

This empty ping has now become a signifier, loaded with meaning. The need for human connection has been distributed, but it does not compensate our need for one-on-one contact. In the early days of the cell phone, when incoming calls were still being charged, the missed call, without any content, was a code between friends and lovers. It had messages about where to meet, when to meet, or sometimes, just that you were missing somebody. The empty ping is the latest avatar of the missed call — in a world where we are always online but not always connected, when we are constantly together, but also spatially and emotionally alone, the ping remains that human touch in the digital space that reassures us that on the other side of that seductive interface and the buzzing gadget, is somebody we can say hello to.

Chances and Risks of Social Participation

programme_participation_woOSHWuNaMiuRBGHMPwNSHIIG2.pdf

—

PDF document,

75 kB (77702 bytes)

programme_participation_woOSHWuNaMiuRBGHMPwNSHIIG2.pdf

—

PDF document,

75 kB (77702 bytes)

Misuse of Surveillance Powers in India (Case 1)

Case 1: Unlawful Phone-tapping in Himachal Pradesh

In December 2012, the government changed in Himachal Pradesh. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) went out of power, and the Indian National Congress (INC) came into power. One of the first things that Chief Minister Virbhadra Singh did, within hours of taking his oath as Chief Minister on December 25, 2012, was to get a Special Investigation Team (SIT) to investigate phone tapping during the BJP government’s tenure.

On December 25th and 26th, 12 hard disk drives were seized from the offices of the Crime Investigation Department (CID) and the Vigilance Department (which is supposed to be an oversight mechanism over the rest of the police). These hard disks showed that 13711 phone numbers were targetted and hundreds of thousands of phone conversations were recorded. These included conversations of prominent leaders “mainly of” the INC but also from the BJP, including three former cabinet ministers and close relatives of multiple chief ministers, a journalist, and many senior police officials, including the Director General of Police.

Violations of the Law

While the law required the state’s Home Secretary to grant permission for each person that was being tapped, the Home Secretary had legitimately only granted permission in 342 cases. This leaves over a thousand cases where phones were tapped illegally, in direct violation of the law. The oversight mechanism provided in the law, namely the Review Committee under Rule 419A of the Indian Telegraph Rules, was utterly powerless to check this. Indeed, the internal checks for the police, namely the Vigilance Department, also seems to have failed spectacularly.

Every private telecom company cooperated in this unlawful surveillance, even though the people who were conducting it did so without proper legal authority. Clearly we need to revise our interception rules to ensure that these telecom companies do not cooperate unless they are served with an order digitally signed by the Home Secretary.

While all interception recordings are required to be destroyed within 6 months as per Rule 419A of the Indian Telegraph Rules, that rule was also evidently ignored and conversations going back to 2009 were being stored.

Concluding Concerns

What should concern us is not merely that such a large number of politicians/police officers were tapped, but that no criminal charges were brought about on the basis of these phone taps, indicating that much of it was being used for political purposes.

What should concern us is that the requirement under Section 5 of the Indian Telegraph Act, which covers phone taps, of the existence of a “public emergency” or endangerment of “public safety”, which is a prerequisite of phone taps as per the law and as emphasised by the Supreme Court in 1996 in the PUCL judgment, were blatantly ignored.

What should concern us is that it took a change in government to actually uncover this sordid tale.

1385 according to a Hindustan Times report [1]: http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/himachal-pradesh-police-registers-first-fir-in-phone-tapping-scandal/1/285698.html↩

A Zee News report states 34 while it’s 171 according to a Mail Today report↩

Sub Tracks

Sub Tracks for Discussion-1.pdf

—

PDF document,

327 kB (334958 bytes)

Sub Tracks for Discussion-1.pdf

—

PDF document,

327 kB (334958 bytes)

Consilience Speakers Profile

Consilience 2013-14 Speakers Profiles-1.pdf

—

PDF document,

451 kB (462811 bytes)

Consilience 2013-14 Speakers Profiles-1.pdf

—

PDF document,

451 kB (462811 bytes)

Brochures from Expos on Smart Cards, e-Security, RFID & Biometrics in India

In Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, many companies from India and abroad gathered to exhibit their products at the following expos which were organised by Electronics Today (India's first electronic exhibition organiser) on 16-18 October 2013:

- SmartCards Expo 2013

- e-Security Expo 2013

- RFID Expo 2013

- Biometrics Expo 2013

The Centre for Internet and Society (CIS) attended these exhibitions for research purposes and is sharing the publicly available brochures it gathered through the attached zip file. The use of these brochures constitutes Fair Use.

Brochures.zip

—

ZIP archive,

78400 kB (80282581 bytes)

Brochures.zip

—

ZIP archive,

78400 kB (80282581 bytes)

Big Brother is watching you

The article by Chinmayi Arun was published in the Hindu on January 3, 2014.

The Gujarat telephone tapping controversy is just one of many kinds of abuse that surveillance systems enable. If a relatively primitive surveillance system can be misused so flagrantly despite safeguards that the government claims are adequate, imagine what is to come with the Central Monitoring System (CMS) and Netra in place.

News reports indicate Netra — a “NEtwork TRaffic Analysis system” — will intercept and examine communication over the Internet for keywords like “attack,” “bomb,” “blast” or “kill.” While phone tapping and the CMS monitor specific targets, Netra is vast and indiscriminate. It appears to be the Indian government’s first attempt at mass surveillance rather than surveillance of predetermined targets. It will scan tweets, status updates, emails, chat transcripts and even voice traffic over the Internet (including from platforms like Skype and Google Talk) in addition to scanning blogs and more public parts of the Internet. Whistle-blower Edward Snowden said of mass-surveillance dragnets that “they were never about terrorism: they’re about economic spying, social control, and diplomatic manipulation. They’re about power.”

So far, our jurisprudence has dealt with only targeted surveillance; and even that in a woefully inadequate manner. This article discusses the slow evolution of the right to privacy in India, highlighting the context and manner in which it is protected. It then discusses international jurisprudence to demonstrate how the right to privacy might be protected more effectively.

Privacy and the Constitution

A proposal to include the right to privacy in the Constitution was rejected by the Constituent Assembly with very little debate. Separately, a proposal to give citizens an explicit fundamental right against unreasonable governmental search and seizure was also put before the Constituent Assembly. This proposal was supported by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. If accepted, it would have included within our Constitution the principles from which the United States derives its protection against state surveillance. However, the proposed amendment was rejected by the Constituent Assembly.

Fortunately, the Supreme Court has gradually been reading the right to privacy into the fundamental rights explicitly listed in the Constitution. After its initial reluctance to affirm the right to privacy in the 1954 case of M.P. Sharma vs. Satish Chandra, the court came around to the view that other rights and liberties guaranteed in the Constitution would be seriously affected if the right to privacy was not protected. In Kharak Singh vs. The State of U.P., the court recognised “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects” and declared that their right against unreasonable searches and seizures was not to be violated. The right to privacy here was conceived around the home, and unauthorised intrusions into homes were seen as interference with the right to personal liberty.

If the Kharak Singh judgment was progressive in its recognition of the right to privacy, it was conservative about the circumstances in which the right applies. The majority of judges held that shadowing a person could not be seen to interfere with that person’s liberty. Dissenting with the majority, Justice Subba Rao maintained that broad surveillance powers put innocent citizens at risk, and that the right to privacy is an integral part of personal liberty. He recognised that when a person is shadowed, her movements will be constricted, and will certainly not be free movements. His dissenting judgment showed remarkable foresight and his reasoning is consistent with what is now a universally acknowledged principle that there is a “chilling effect” on expression and action when people think that they are being watched.

The right to privacy as defined by the Supreme Court now extends beyond government intrusion into private homes. After Govind vs. State of M.P., and Dist. Registrar and Collector of Hyderabad vs. Canara Bank, this right is seen to protect persons and not places. Any inroads into this right for surveillance of communication must be for permissible reasons and according to just, fair and reasonable procedure. State action in violation of this procedure is open to a constitutional challenge.

Our meagre procedural safeguards against phone tapping were introduced in PUCL vs. Union of India (1997) after the Supreme Court was confronted with extensive, undocumented phone tapping by the government. The apex court found itself compelled to lay down what it saw as bare minimum safeguards, consisting mostly of proper record-keeping and internal executive oversight by senior officers such as the home secretary, the cabinet secretary, the law secretary and the telecommunications secretary. These safeguards are of little use since they are opaque and rely solely on members of the executive to review surveillance requests.

Right and safeguards

There is a difference between targeted surveillance in which reasons have to be given for surveillance of particular people, and the mass-surveillance which Netra sets up. The question of mass surveillance and its attendant safeguards has been considered by the European Court of Human Rights in Liberty and Others vs. the United Kingdom. Drawing upon its own past jurisprudence, the European Court insisted on reasonable procedural safeguards. It stated quite clearly that there are significant risks of arbitrariness when executive power is exercised in secret and that the law should be sufficiently clear to give citizens an adequate indication of the circumstances in which interception might take place. Additionally, the extent of discretion conferred and the manner of its exercise must be clear enough to protect individuals from arbitrary interference. The principles laid down by the European Court in relation to phone-tapping also require that the nature of the offences which may give rise to an interception order, the procedure to be followed for examining, using and storing the data obtained, the precautions to be taken when communicating the data to other parties, and the circumstances in which recordings may or must be erased or the tapes destroyed be made clear.

Opaque and ineffective

Our safeguards apply only to targeted surveillance, and require written requests to be provided and reviewed before telephone tapping or Internet interception is carried out. CMS makes the process of tapping more prone to misuse by the state, by making it even more opaque: if the state can intercept communication directly, without making requests to a private telecommunication service provider, then it is one less layer of scrutiny through which the abuse of power can reach the public. There is no one to ask whether the requisite paperwork is in place or to notice a dramatic increase in interception requests.

India has no requirements of transparency whether in the form of disclosing the quantum of interception taking place each year, or in the form of subsequent notification to people whose communication was intercepted. It does not even have external oversight in the form of an independent regulatory body or the judiciary to ensure that no abuse of surveillance systems takes place. Given these structural flaws, the Amit Shah controversy is just the beginning of what is to come. Unfettered mass surveillance does not bode well for democracy.

(Chinmayi Arun is research director, Centre for Communication Governance, National Law University, Delhi, and fellow, Centre for Internet and Society, Bangalore.)

Letter requesting public consultation on position of GoI at WGEC

January 3, 2014

Shri Kapil Sibal,

Honourable Minister for Communication and Information Technology

Ministry of Communication and Information Technology,

Government of India

Subject: Public consultation at the domestic level on the position of Government of India at WGEC

Dear Sir,

We at the Centre for Internet and Society, Bangalore (“CIS”) commend, Government of India’s participation at the Working Group on Enhanced Cooperation (WGEC), working under the aegis of United Nations Commission on Science and Technology and Development (CSTD). The Working Group was set up in pursuance of General Assembly Resolution A/Res/67/195, to identify a shared understanding of enhanced cooperation on public policy issues pertaining to the internet. The WGEC after its first meeting circulated a questionnaire to collect the views and positions of the stakeholders on various aspects of enhanced cooperation. The Government of India responded to the questionnaire and also represented its position at the second meeting of WGEC held in Geneva from November 6-8, 2013. We would like the Government to take cognizance of representations from concerned stakeholders before finalizing its position.

In this regard, we would like to note, Government of India’s commitment towards multi-stakeholder approach in formulation of public policy pertaining to the internet. At the Internet Governance Forum, 2012 held in Baku, the Honourable Minister for Communications and Information Technology noted that the “issues of public policy related to the internet have to be dealt with, by adopting a multi-stakeholder, democratic and transparent approach”. Furthermore, the Government of India’s stand at the World Conference on International Telecommunications, 2012 in Dubai supported and recognized the multi-stakeholder nature of the internet.

However, it seems that the Government has digressed from its previous stand on internet governance whereas it fell short of having a multi-stakeholder public consultation on India’s position on enhanced cooperation at the WGEC. We earnestly urge you to hold domestic public consultation before the next WGEC meeting.

Thank you.

Sincerely,

Snehashish Ghosh,

Policy Associate,

Centre for Internet and Society, Bangalore

Copied to: Dr. Ajay Kumar, Joint Secretary, DietY, MOCIT and Shri. J. Satyanarayana, Secretary, DietY, MOCIT

Letter on WGEC

Letter on WGEC.pdf

—

PDF document,

315 kB (323404 bytes)

Letter on WGEC.pdf

—

PDF document,

315 kB (323404 bytes)

Internet Monitor

SSRN-id2366840.pdf

—

PDF document,

7223 kB (7396414 bytes)

SSRN-id2366840.pdf

—

PDF document,

7223 kB (7396414 bytes)

India's Identity Crisis

India’s Unique Identity (UID) project is already the world’s largest biometrics identity program, and it is still growing. Almost 530 million people have been registered in the project database, which collects all ten fingerprints, iris scans of both eyes, a photograph, and demographic information for each registrant. Supporters of the project tout the UID as a societal game changer. The extensive biometric information collected, they argue, will establish the uniqueness of each individual, eliminate fraud, and provide the identity infrastructure needed to develop solutions for a range of problems. Despite these potential benefits, however, critical concerns remain about the UID’s legal and physical architecture as well as about unforeseen risks associated with the linking and analysis of personal data.

The most basic concerns regarding the UID project stem from the fact that biometric technologies have never been tested on such a large population. As a result, well-founded concerns exist around scalability, false acceptance and rejection rates, and the project’s core premise that biometrics can uniquely and unambiguously identify people in a foolproof manner. Some of these concerns are based on technical issues—collecting fingerprints and iris scans “in the field,” for instance, can be complicated when a registrant’s fingerprints are eroded by manual labor or her irises are affected by malnutrition and cataracts. Other concerns relate to the project’s federated implementation architecture, which, by outsourcing collection to a massive group of private and public registrars and operators, increases the chance for data breaches, error, and fraud.

Perhaps even more vexing are concerns regarding how the UID, which promises financial inclusion (by reducing the identification barriers to opening bank accounts, for example), might in fact lead to new types of exclusion for already marginalized groups. Members of the LGBT community, for instance, question whether the inclusion of the transgender category within the UID scheme is a laudable attempt at inclusion, or a new means of listing and targeting members of their community for exclusion. More fundamentally, as more and more services and benefits are linked to the UID, the project threatens to exclude all those who cannot or will not participate in the scheme due to logistical failures or philosophical objections.

It is worth noting that the UID is not the only large data project in India. A slew of “Big Brother” projects exist: the Centralised Monitoring System (CMS), the Telephone Call Interception System (TCIS), the National Population Register (NPR), the Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and Systems (CCTNS), and the National Intelligence Grid (NATGRID), which is working to aggregate up to 21 different databases relating to tax, rail and air travel, credit card transactions, immigration, and other domains. The UID is intended to serve as a common identifier across these databases, creating a massive surveillance state. It also facilitates an ecosystem where access to goods and services, from government subsidies to drivers’ licenses to mobile phones to cooking gas, increasingly requires biometric authentication.

The UID project was originally vaunted as voluntary, but the inexorable slippery slope toward compulsory participation has triggered a series of lawsuits challenging the legality of forced enrollment and the constitutionality of the entire project. Most recently, in September 2013, India’s federal Supreme Court affirmed by way of an interim decision that the UID was not mandatory, that not possessing a UID should not disadvantage anybody, and that citizenship should be ascertained as a criteria for registering in order to ensure that UIDs are not issued to illegal immigrants. This last stipulation is particularly thorny given that the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI, the body in charge of the UID project) has consistently distanced the UID from questions of citizenship under the justification that it is a matter beyond their remit (i.e., the UID is open to residents, and is not linked to citizenship). The government moved quickly to urge a modification of the order, but the Supreme Court declined to do so and will instead release its final decision after it reviews a batch of petitions from activists and others. The UIDAI approached the court, arguing that not making the UID mandatory has serious consequences for welfare schemes, but the court recently ordered the federal government, the Reserve Bank of India, and the Election Commission to delink the LPG cooking gas scheme from the UID. This is a considerable setback for the project, given that this was one of the most hyped linkages for the UID. It remains to be seen whether the court will similarly halt other attempts to make the UID mandatory.

In the meantime, the UID project is effectively being implemented in a legal vacuum without support from the Supreme Court or Parliament. The Cabinet is seeking to rectify this and has cleared a bill that would finally provide legal backing for the UID program—its previous attempt was rejected by the Standing Committee on Finance in 2010. This bill is scheduled to come up for debate during the winter session of Parliament. The bill’s progress, along with the final decision of the Supreme Court, will have far reaching consequences for the UID project’s implementation and longevity, as well as for the relationship between India’s citizens and the state.

If fully implemented, the UID system will fundamentally alter the way in which citizens interact with the government by creating a centrally controlled, technology-based standard that mediates access to social services and benefits, financial systems, telecommunications, and governance. It will undoubtedly also have implications for how citizens relate to private sector entities, on which the UID rests and which have their own vested interests in the data. The success or failure of the UID represents a critical moment for India. Whatever course the country takes, its decision to travel further toward or turn away from becoming a “database nation” will have implications for democracy, free speech, and economic justice within its own borders and also in the many neighboring countries that look to it as a technological standard bearer.

The Indian government seems to envision “big data” as a panacea for fraud, corruption, and abuse, but it has given little attention to understanding and addressing the fraud, corruption, and abuse that massive databases can themselves engender. The government’s actions have yet to demonstrate an appreciation for the fact that the matrix of identity and surveillance schemes it has implemented can create a privacy-invading technology layer that is not only a barrier to online activity but also to social participation writ large.

The lack of identification documents for a large portion of the Indian population does need to be addressed. Whether the UID project is the best means to do this—whether it has the right architecture and design, whether it can succeed without an overhaul of several other failures of governmental institutions, and whether fixing the identity piece alone causes more harm than good—should be the subject of intense debate and scrutiny. Only through rigorous threat modeling and analysis of the risks arising out of this burgeoning “data industrial complex” can steps be taken to stem the potential repercussions of the project not just for identity management, fraud, corruption, distributive justice, and welfare generally, but also for autonomy, openness, and democracy.

Click to download the article published in the annual report of Berkman's Center for Internet and Society (PDF 7223 Kb)

Surveillance and the Indian Constitution - Part 1: Foundations

Note: This was originally posted on the Indian Constitutional Law and Philosophy blog.

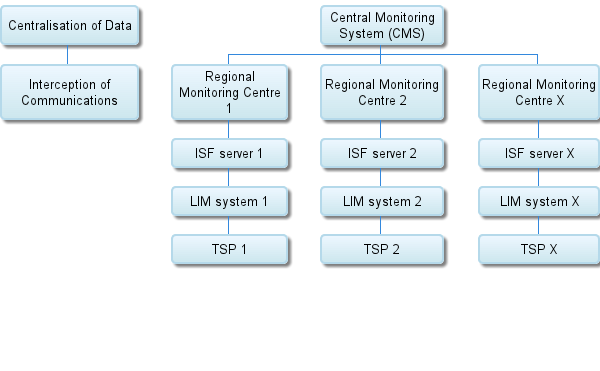

On previous occasions, we have discussed the ongoing litigation in ACLU v. Clapper in the United States, a challenge to the constitutionality of the National Security Agency’s (NSA) bulk surveillance program. Recall that a short while after the initial Edward Snowden disclosures, The Hindu revealed the extent of domestic surveillance in India, under the aegis of the Central Monitoring System (CMS). The CMS (and what it does) is excellently summarized here. To put thing starkly and briefly:

“With the C.M.S., the government will get centralized access to all communications metadata and content traversing through all telecom networks in India. This means that the government can listen to all your calls, track a mobile phone and its user’s location, read all your text messages, personal e-mails and chat conversations. It can also see all your Google searches, Web site visits, usernames and passwords if your communications aren’t encrypted.”

The CMS is not sanctioned by parliamentary legislation. It also raises serious privacy concerns. In order to understand the constitutional implications, therefore, we need to investigate Indian privacy jurisprudence. In a series of posts, we plan to discuss that.

Privacy is not mentioned in the Constitution. It plays no part in the Constituent Assembly Debates. The place of the right – if it exists – must therefore be located within the structure of the Constitution, as fleshed out by judicial decisions. The first case to address the issue was M. P. Sharma v. Satish Chandra, in 1954. In that case, the Court upheld search and seizure in the following terms:

"A power of search and seizure is in any system of jurisprudence an overriding power of the State for the protection of social security and that power is necessarily regulated by law. When the Constitution makers have thought fit not to subject such regulation to Constitutional limitations by recognition of a fundamental right to privacy, analogous to the American Fourth Amendment, we have no justification to import it, into a totally different fundamental right. by some process of strained construction."

The right in question was 19(1)(f) – the right to property. Notice here that the Court did not reject a right to privacy altogether – it only rejected it in the context of searches and seizures for documents, the specific prohibition of the American Fourth Amendment (that has no analogue in India). This specific position, however, would not last too long, and was undermined by the very next case to consider this question, Kharak Singh.

In Kharak Singh v. State of UP, the UP Police Regulations conferred surveillance power upon certain “history sheeters” – that is, those charged (though not necessarily convicted) of a crime. These surveillance powers included secret picketing of the suspect’s house, domiciliary visits at night, enquiries into his habits and associations, and reporting and verifying his movements. These were challenged on Article 19(1)(d) (freedom of movement) and Article 21 (personal liberty) grounds. It is the second ground that particularly concerns us.

As a preliminary matter, we may observe that the Regulations in question were administrative – that is, they did not constitute a “law”, passed by the legislature. This automatically ruled out a 19(2) – 19(6) defence, and a 21 “procedure established by law” defence – which were only applicable when the State made a law. The reason for this is obvious: fundamental rights are extremely important. If one is to limit them, then that judgment must be made by a competent legislature, acting through the proper, deliberative channels of lawmaking – and not by mere administrative or executive action. Consequently – and this is quite apart from the question of administrative/executive competence - if the Police Regulations were found to violate Article 19 or Article 21, that made them ipso facto void, without the exceptions kicking in. (Paragraph 5)

It is also important to note one other thing: as a defence, it was expressly argued by the State that the police action was reasonable and in the interests of maintaining public order precisely because it was “directed only against those who were on proper grounds suspected to be of proved anti-social habits and tendencies and on whom it was necessary to impose some restraints for the protection of society.” The Court agreed, observing that this would have “an overwhelming and even decisive weight in establishing that the classification was rational and that the restrictions were reasonable and designed to preserve public order by suitable preventive action” – if there had been a law in the first place, which there wasn’t. Thus, this issue itself was hypothetical, but what is crucial to note is that the State argued – and the Court endorsed – the basic idea that what makes surveillance reasonable under Article 19 is the very fact that it is targeted – targeted at individuals who are specifically suspected of being a threat to society because of a history of criminality.

Let us now move to the merits. The Court upheld secret picketing on the ground that it could not affect the petitioner’s freedom of movement since it was, well secret – and what you don’t know, apparently, cannot hurt you. What the Court found fault with was the intrusion into the petitioner’s dwelling, and knocking at his door late at night to wake him up. The finding required the Court to interpret the meaning of the term “personal liberty” in Article 21. By contrasting the very specific rights listed in Article 21, the Court held that:

“Is then the word “personal liberty” to be construed as excluding from its purview an invasion on the part of the police of the sanctity of a man’s home and an intrusion into his personal security and his right to sleep which is the normal comfort and a dire necessity for human existence even as an animal? It might not be inappropriate to refer here to the words of the preamble to the Constitution that it is designed to “assure the dignity of the individual” and therefore of those cherished human value as the means of ensuring his full development and evolution. We are referring to these objectives of the framers merely to draw attention to the concepts underlying the constitution which would point to such vital words as “personal liberty” having to be construed in a reasonable manner and to be attributed that these which would promote and achieve those objectives and by no means to stretch the meaning of the phrase to square with any preconceived notions or doctrinaire constitutional theories.” (Paragraph 16)

A few important observations need to be made about this paragraph. The first is that it immediately follows the Court’s examination of the American Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, with their guarantees of “life, liberty and property…” and is, in turn, followed by the Court’s examination of the American Fourth Amendment, which guarantees the protection of a person’s houses, papers, effects etc from unreasonable searches and seizures. The Court’s engagement with the Fourth Amendment is ambiguous. It admits that “our Constitution contains no like guarantee…”, but holds that nonetheless “these extracts [from the 1949 case, Wolf v Colorado] would show that an unauthorised intrusion into a person’s home and the disturbance caused to him thereby, is as it were the violation of a common law right of a man – an ultimate essential of ordered liberty”, thus tying its own holding in some way to the American Fourth Amendment jurisprudence. But here’s the crucial thing: at this point, American Fourth Amendment jurisprudence was propertarian based – that is, the Fourth Amendment was understood to codify – with added protection – the common law of trespass, whereby a man’s property was held sacrosanct, and not open to be trespassed against. Four years later, in 1967, in Katz, the Supreme Court would shift its own jurisprudence, to holding that the Fourth Amendment protected zones where persons had a “reasonable expectation of privacy”, as opposed to simply protecting listed items of property (homes, papers, effects etc). Kharak Singh was handed down before Katz. Yet the quoted paragraph expressly shows that the Court anticipated Katz, and in expressly grounding the Article 21 personal liberty right within the meaning of dignity, utterly rejected the propertarian-tresspass foundations that it might have had. To use a phrase invoked by later Courts – in this proto-privacy case, the Court already set the tone by holding it to attach to persons, not places.

While effectively finding a right to privacy in the Constitution, the Court expressly declined to frame it that way. In examining police action which involved tracking a person’s location, association and movements, the Court upheld it, holding that “the right of privacy is not a guaranteed right under our Constitution and therefore the attempt to ascertain the movements of an individual which is merely a manner in which privacy is invaded is not an infringement of a fundamental right guaranteed by Part III.”

The “therefore” is crucial. Although not expressly, the Court virtually holds, in terms, that tracking location, association and movements does violate privacy, and only finds that constitutional because there is no guaranteed right to privacy within the Constitution. Yet.

In his partly concurring and partly dissenting opinion, Subba Rao J. went one further, by holding that the idea of privacy was, in fact, contained within the meaning of Article 21: “it is true our Constitution does not expressly declare a right to privacy as a fundamental right, but the said right is an essential ingredient of personal liberty.” Privacy he defined as the right to “be free from restrictions or encroachments on his person, whether those restrictions or encroachments are directly imposed or indirectly brought about by calculated measures.” On this ground, he held all the surveillance measures unconstitutional.

Justice Subba Rao’s opinion also explored a proto-version of the chilling effect. Placing specific attention upon the word “freely” contained within 19(1)(d)’s guarantee of free movment, Justice Subba Rao went specifically against the majority, and observed:

“The freedom of movement in clause (d) therefore must be a movement in a free country, i.e., in a country where he can do whatever he likes, speak to whomsoever he wants, meet people of his own choice without any apprehension, subject of course to the law of social control. The petitioner under the shadow of surveillance is certainly deprived of this freedom. He can move physically, but he cannot do so freely, for all his activities are watched and noted. The shroud of surveillance cast upon him perforce engender inhibitions in him and he cannot act freely as he would like to do. We would, therefore, hold that the entire Regulation 236 offends also Art. 19(1)(d) of the Constitution.”

This early case, therefore, has all the aspects that plague the CMS today. What to do with administrative action that does not have the sanction of law? What role does targeting play in reasonableness – assuming there is a law? What is the philosophical basis for the implicit right to privacy within the meaning of Article 21’s guarantee of personal liberty? And is the chilling effect a valid constitutional concern?

We shall continue with the development of the jurisprudence in the next post.

You can follow Gautam Bhatia on Twitter

Electoral Databases – Privacy and Security Concerns

The recent move by the Election Commission of India (ECI) to tie-up with Google for providing electoral look-up services for citizens and electoral information services has faced heavy criticism on the grounds of data security and privacy.[i] After due consideration, the ECI has decided to drop the plan.[ii]

The plan to partner with Google has led to much apprehension regarding Google gaining access to the database of 790 million voters including, personal information such as age, place of birth and residence. It could have also gained access to cell phone numbers and email addresses had the voter chosen to enroll via the online portal on the ECI website. Although, the plan has been cancelled, it does not necessarily mean that the largest database of citizens of India is safe from any kind of security breach or abuse. In fact, the personal information of each voter in a constituency can be accessed by anyone through the ECI website and the publication of electoral rolls is mandated by the law.

Publication of Electoral Rolls

The electoral roll essentially contains the name of the voter, name of the relationship (son of/wife of, etc.), age, sex, address and the photo identity card number. The main objective of creation and maintenance of electoral rolls and the issue of Electoral Photo Identity Card (EPIC) was to ensure a free and fair election where the voter would have been able to cast his own vote as per his own choice. In other words, the main purpose of the exercise was to curtail bogus voting. This is achieved by cross referencing the EPIC with the electoral roll.

The process of creation and maintenance of electoral rolls is governed by the Registration of Electors Rules, 1960. Rule 22 requires the registration officer to publish the roll with list of amendments at his office for inspection and public information. Furthermore, ECI may direct the registration officer to send two copies of the electoral roll to every political party for which a symbol has exclusively been reserved by the ECI. It can be safely concluded that the electoral roll of a constituency is a public document[iii] given that the roll is published and can be circulated on the direction of the ECI.

With the computational turn, in 1998 the ECI took the decision to digitize the electoral databases. Furthermore, printed electoral rolls and compact discs containing the rolls are available for sale to general public.[iv] In addition to that, the electoral rolls for the entire country are available on the ECI website.[v] However, the current database is not uniform and standardized, and entries in some constituencies are available only in the local language. The ECI has taken steps to make the database uniform, standardized and centralized.[vi]

Security Concerns

The Registration of Electoral Rules, 1960 is an archaic piece of delegated legislation which is still in force and casts a statutory duty on the ECI to publish the electoral rolls. The publication of electoral rolls is not a threat to security when it is distributed in hard copies and the availability of electoral rolls is limited. The security risks emerge only after the digitization of electoral database, which allows for uniformity, standardization and centralization of the database which in turn makes it vulnerable and subject to abuse. The law has failed to evolve with the change in technology.

In a recent article, Bill Davidow analyzes "the dark side of Moore’s Law" and argues that with the growth processing power there has been a growth in surveillance capabilities and on this note the article is titled, “With Great Computing Power Comes Great Surveillance”[vii] Drawing from Davidow’s argument, with the exponential growth in computing power, search has become convenient, faster and cheap. A uniform, standardized and centralized database bearing the personal information of 790 million voters can be searched and categorized in accordance with the search terms. The personal information of the voters can be used for good, but it can be equally abused if it falls into the wrong hands. Big data analysis or the computing power makes it easier to target voters, as bits and pieces of personal information give a bigger picture of an individual, a community, etc. This can be considered intrusive on individual’s privacy since the personal information of every voter is made available in the public domain

For example, the availability of a centralized, searchable database of voters along with their age would allow the appropriate authorities to identify wards or constituencies, which has a high population of voters above the age of 65. This would help the authority to set up polling booths at closer location with special amenities. However, the same database can be used to search for density of members of a particular community in a ward or constituency based on the name, age, sex of the voters. This information can be used to disrupt elections, target vulnerable communities during an election and rig elections.

Current IT Laws does not mandate the protection of the electoral database

A centralized electoral database of the entire country can be considered as a critical information infrastructure (CII) given the impact it may have on the election which is the cornerstone of any democracy. Under Section 70 of the Information Technology Act, 2000 (IT Act) CII means “the computer resource, incapacitation or destruction of which, shall have debilitating impact on national security, economy.”[viii] However, the appropriate Government has not notified the electoral database as a protected system[ix]. Therefore, information security practices and procedures for a protected system are not applicable to the electoral database.

The Information Technology Rules (IT Rules) are also not applicable to electoral databases, per se. Since, ECI is not a body corporate, the Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information), Rules, 2011 (hereinafter Reasonable Security Practices Rules) do not apply to electoral databases. Ignoring that Reasonable Security Practices Rules only apply to a body corporate, the electoral database does fall within the ambit of definition of “personal information”[x] and should arguably be made subject to the Rules.

The intent of the ECI for hosting the entire country’s electoral database online inter alia is to provide electronic service delivery to the citizens. It seeks to provide “electoral look up services for citizens ... for better electoral information services.”[xi] However, the Information Technology (Electronic Service Delivery) Rules, 2011 are not applicable to the electoral database given that it is not notified by the appropriate Government as a service to be delivered electronically. Hence, the encryption and security standards for electronic service delivery are not applicable to electoral rolls.

The IT Act and the IT Rules provide a reasonable scope for the appropriate Government to include electoral databases within the ambit of protected system and electronic service delivery. However, the appropriate government has not taken any steps to notify electoral database as protected system or a mode of electronic service delivery under the existing laws.

Conclusion

Publication of electoral rolls is a necessary part of an election process. It ensures free and fair election and promotes transparency and accountability. But unfettered access to electronic electoral databases may have an adverse effect and would endanger the very goal it seeks to achieve because the electronic database may pose threat to privacy of the voters and also lead to security breach. It may be argued that the ECI is mandated by the law to publish the electoral database and hence, it is beyond the operation of the IT Act. But Section 81 of the IT Act has an overriding effect on any law inconsistent, therewith. The appropriate Government should take necessary steps under the IT Act and notify electoral databases as a protected system.

It is recommended that the Electors Registration Rules, 1960 should be amended, taking into account the advancement in technology. Therefore, the Rules should aim at restricting the unfettered electronic access to the electoral database and also introduce purposive limitation on the use of the electoral database. It should also be noted that more adequate and robust data protection and privacy laws should be put in place, which would regulate the collection, use, storage and processing of databases which are critical to national security.

[i] Pratap Vikram Singh, Post-uproar, EC’s Google tie-up plan may go for a toss, Governance Now, January 7, 2014 available at http://www.governancenow.com/news/regular-story/post-uproar-ecs-google-tie-plan-may-go-toss

[ii] Press Note No.ECI/PN/1/2014, Election Commission of India , January 9, 2014 available at http://eci.nic.in/eci_main1/current/PN09012014.pdf

[iii] Section 74, Indian Evidence Act, 1872

[vi] “At present, in most States and UTs the Electoral Database is kept at the district level. In some cases it is kept even with the vendors. In most States/UTs it is maintained in MS Access, while in some cases it is on a primitive technology like FoxPro and in some other cases on advanced RDBMS like Oracle or Sql Server. The database is not kept in bilingual form in some of the States/UTs, despite instructions of the Commission. In most cases Unicode fonts are not used. The database structure not being uniform in the country, makes it almost impossible for the different databases to talk to each other” – Election Commission of India, Revision of Electoral Rolls with reference to 01-01-2010 as the qualifying date – Integration and Standardization of the database- reg., No. 23/2009-ERS, January 6, 2010 available at eci.nic.in/eci_main/eroll&epic/ins06012010.pdf

[vii] http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2014/01/with-great-computing-power-comes-great-surveillance/282933/

[viii] Section 70, Information Technology Act, 2000

[ix] Computer resource which directly or indirectly affects the facility of Critical Information Infrastructure

[x] Rule 2(1)(i), Information Technology (Reasonable Security Practices and Procedures and Sensitive Personal Data or Information) Rules, 2011

[xi] Press Note No.ECI/PN/1/2014, Election Commission of India , January 9, 2014 available at http://eci.nic.in/eci_main1/current/PN09012014.pdf

GNI Assessment Finds ICT Companies Protect User Privacy and Freedom of Expression

Introduction

In January 2014, the Global Network Initiative (GNI) published the Public Report on the Independent Assessment Process for Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo. GNI is an industry consortium that was started in 2008 with the objective of protecting user’s right to privacy and freedom of expression globally. The main objectives of GNI are to provide a framework for companies that is based on international standards, ensure accountability of ICT companies through independent assessments, create opportunities for policy engagement, and create opportunities for stakeholders from multiple jurisdictions to engage in dialogue with each other. The Centre for Internet and Society, Bangalore, is a member of GNI. Companies based in India have yet to join as members to the GNI network.

Overview of the Public Report

The Public Report provides an overview of assessments completed on the practices and policies of Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft from 2011 - 2013 to measure company compliance with the GNI principles on freedom of expression and privacy. The principles lay out broad guidelines that member companies should seek to incorporate in their internal and external practices and speak to freedom of expression, privacy, responsible company decision making, multi – stakeholder collaboration, and organizational governance, accountability, and transparency. The GNI principles have also been developed with Implementation Guidelines to provide companies with a framework for companies to respond to government requests. The assessment carried out by GNI reviewed cases in each company pertaining to governmental: blocking and filtering, takedown requests, criminalization of speech, intermediary liability, selective enforcement, content surveillance, and requests for user information.

Importantly, the assessment undertaken by GNI finds Yahoo, Microsoft, and Google to be in compliance with the GNI principles on freedom of expression and privacy. The Report highlights practices by the companies that work to protect freedom of expression and privacy such as conducting human rights impact assessments, issuing transparency reports, and notifying affected users when content is removed, have been, adopted by these companies. For example, Google conducts Human Rights Impact Assessments to assess potential threats to freedom of expression and privacy. Google also has in place internal processes to review governmental requests impacting freedom of expression and privacy, and the legal team at Google prepares a “global removal report” to provide a bird’s eye view of trends emerging from content removal requests. If Google has the email address of a user who’s posted content is removed, Google will often notify the user and directs the user to the Chilling Effects website. Google has also published a transparency report since 2010. Like Google, Microsoft conducts Human Rights Impact Assessments before making decisions on whether to incorporate certain features into its platforms when operating in high risk markets. Microsoft has also issued two global law enforcement requests reports in 2013. Yahoo has established a Business and Human Rights Program to ensure responsible actions are taken by the company with regards to freedom of expression and privacy, and now issues transparency reports about government requests. Yahoo’s Public Policy team also engages in dialogue with governments on an international level about existing and proposed legislation impacting and implicating privacy and freedom of expression.

The Report highlights challenges to compliance with the GNI principles that companies face – namely legal restraints and mandates that they are faced with. On the issue of transparency, the assessment found that companies do not disclose information when there are legal prohibitions on such disclosure, when users privacy would be implicated, when companies choose to assert attorney client privilege, and when trade secrets are involved. Despite this, the assessment found that companies do deny and push back on governmental requests impacting freedom of expression and privacy for reasons such as the request needed clarification and modification, or that the request needed to follow established procedure.

A number of findings came out of the assessments undertaken for the Report including:

- As demonstrated by the lack of ability to access information about secret national security requests, and the lack of ability for companies to disclose information on this topic there is a dire need for governments to reform surveillance policy and law impacting freedom of expression and privacy.

- The implementation of the GNI Principles is challenging when a company is undergoing an acquisition. In this scenario, contractual provisions limiting third party disclosure are critical in ensuring protection of privacy and free expression rights.

- Companies need to pro-actively and on an ongoing basis internally review governmental restrictions on content to determine if it is in compliance with the commitment made by that company to the GNI Principles.

The assessment resulted in GNI defining a number of actionable (non-binding) recommendations for companies such as:

- Improving the integration of human rights considerations in the due diligence process with respect to the acquiring and selling companies.

- Consider the impact of hardware on freedom of expression and privacy.

- Improve external and internal reporting.

- Review employee access to user data to ensure that employee access rights are restricted by both policy and technical measures on a ‘need to know’ basis across global operations.

- Review executive management training.

- Improve stakeholder engagement.

- Improve communication with users.

- Increase sharing of best practices.

- The GNI principles are focused on freedom of expression and privacy and are based on internationally recognized laws and standards for human rights.

NSA leaks, global push for governmental surveillance reform, and the Public Report

With special attention given to the various companies responses to the NSA leaks, the Report notes that in response to the NSA leaks the assessed companies have issued public statements and filed legal challenges with the US government and filed suit with the FISA Court seeking the right to disclose data relating to the number of FISA requests received with the public. All three companies have also supported legislation and policy that would allow for such transparency. Furthermore in December 2014, the companies , along with other internet companies, developed and issued the five Principles on Global Government Surveillance Reform. Similar to other efforts to end mass and disproportionate surveillance, such as the Necessary and Proportionate principles, the Principles on Global Government Surveillance Reform address: Limiting Governments’ Authority to Collect Users’ Information, Oversight and Accountability, Transparency about Government Demands, Respecting the Free Flow of Information, Avoiding Conflicts Among Governments. Other companies that signed these principles include AOL, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter.

Along these lines, on January 14th, GNI released the statement “Surveillance Reforms to Protect Rights and Restore Trust”, urging the U.S Government to review and enact surveillance legislation that incorporate a ‘rights based’ approach to issues involving national security. In the statement, GNI specifically recommends the Government to action and: end mass collection of communications metadata, protect and uphold the rights of non-Americans, continue to increase transparency of surveillance practices, support the use of strong encryption standards.

Conclusion and way forward

Looking ahead, GNI is planning on developing and implementing a mechanism to address effectively address consumer engagement and complaints issued by individuals who feel that GNI member companies have not acted consistently with the commitments made as a GNI member. GNI is also looking to expand work around public policy and surveillance.

The Public Report on the Independent Assessment Process for Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo is an important step towards ensuring ICT sector companies are accountable to the public in their practices impacting freedom of expression and privacy. The assessment comes at a time when ICT companies often find themselves stuck between a rock and a hard place – with Governments issuing surveillance and censorship demands with mandates for non-disclosure, and the public demanding transparency, company resistance to such demands from the Government, and a strong commitment to users freedom of expression and privacy. Hopefully, the GNI assessment is and will evolve into a middle ground for ICT companies – where they can be accountable to the public and their customers and compliant with Governmental mandates in all jurisdictions that they operate in. It will be interesting to see if in the future Indian companies join GNI as members and being to adopt the GNI principles and undergo GNI assessments.

Interview with Mathew Thomas from the Say No to UID campaign - UID Court Cases

Hi Mathew! We've heard that you've been in court a lot over the last few years with regards to the UID scheme. Could you please tell us about the UID case you have filed?

In early 2012, I filed a civil suit at the Bangalore Court to declare the UID scheme illegal and to stop further biometric enrollments. I alleged that foreign agencies are involved in the process of biometric enrollment, and that cases of corruption have occurred with regards to the companies contracted by the UID Authority of India (UIDAI). Many dubious companies have been empanelled for biometric enrollments by the UIDAI and many cases of corruption have been noted, especially with regards to the preparation of biometric databases for below poverty line (BPL) ration cards in Karnataka.

In 2010, according to a government audit report, COMAT Technologies Private Limited had a contract with the Karnataka Government and was required to undertake a door-to-door survey and to set up biometric devices. COMAT Technologies Private Limited was paid ₹ 542.3 million for this purpose, but it turns out that the company did not comply with the terms of the contract and did not fullfill its obligations under the contract. Even though COMAT Technologies Private Limited had been contracted and had been paid ₹ 542.3 million, the company did not hand over any biometric device to the Karnataka Government. Instead, when the company got questioned, it walked away from the contract in 2010, even though it had been paid for a service it did not deliver.

In the same year, 2010, COMAT Technologies was empanelled as an Enrolling Agency of the UIDAI. COMAT Technologies also carries out enrollments in Mysore and a TV channel sting operation revealed that fake IDs were being issued in the Mysore enrollment center. After much persuasion, the e-Government department of Karnataka informed me that they have filed an FIR. And this is just one case of a corrupt company empanelled as an enrollement agency with the UIDAI. Many similar cases with other companies have occurred in other cities in India, such as Mumbai, where the empanelled agencies have committed fraud and police complaints have been filed. But unfortunately, there is no publicly available information on the state of the investigations.

As such, I filed a case at the Bangalore Court and stated that the whole UID system is insecure, that it will not achieve the objective of preventing leakages of welfare subsidies and that, therefore, it is a waste of public funds, which also affects individuals' right to privacy and right to life. In my complaint in the civil court I made allegations of corruption and dangers to national security backed by documentary evidence. According to Order 8 of the Civil Procedure Code (CPC), defendants are required to specifically deny each of the allegations against them and if they don't, the court is required to accept the allegations as accurate. According to law, vague, bald denials are not acceptable in courts. Interestingly enough, the defendants in this court case did not deny any of the allegations, but instead stated that they (allegations) are “trivial” and requested the judge to dismiss the case without a trial. The judge requested the defendants to file a written application, asking for the suit to be dismissed under Order 7, Rule 11, of the Civil Procedure Code. Nonetheless, in May 2012, the judge observed that this is a serious case which should not be dismissed and that he would like to have a daily hearing of the case, especially since the case was grounded on the allegation that thousands of crores of rupees of public money are spent every day.

However, one month later in June 2012, the judge dismissed the case by stating that I did not have a “cause of action” and that the case is not of civil nature under Section 9 of the Code of Civil Procedure. I argued that tax payers have a right to know where their money is going and that we all have a right to privacy and that therefore, I did have a cause for action. I quoted the Supreme Court case setting out the law relating to the meaning of “civil nature”. The Apex court said, “Anything which is not of criminal nature is of civil nature”. I also quoted several court precedents which explained conditions under which complaints could be dismissed under Order VII Rule 11. Unfortunately though, the judge dismissed all of this and suggested that I should take this case to the High Court or to the Supreme Court, since the Bangalore Court did not have the authority to address the violation of fundamental human rights. In my opinion, the fallacy in this judgement was that, on the one hand, the judge stated in his order that there was “no cause for action”, but on the other hand, he said that I should take the case to the High Court or to the Supreme Court! And on top of that, the judge stated that my case was frivolous and levied on me a Rs. 25, 000 fine, because apparently I was “wasting the court's time” !

In addition to all of this, the judge made a very intriguing statement in his order: he claimed that the biometric enrollment with the UIDAI is voluntary and that therefore I need not enrol. I argued that although the UID is voluntary in theory, it is actually mandatory on many levels, especially since access to many governmental services require enrollment with the UIDAI. Nonetheless, the judge insisted that the UID is purely voluntary and that if I am not happy with the UID, then I should just “stay at home”.

And how did the case continue thereafter?

In October 2012 I appealed against this to the High Court by stating that there was a misapplication of Order 7, Rule 11, of the Civil Procedure Code and requested the High Court to send the suit back for trial at the Bangalore Court.

Now, when you appeal in India, the Court has to issue notices to the opposite party, which are usually sent by registered post. However, nothing was happening, so I filed a number of applications to hear the case. The registrar’s office filed a number of trivial “objections” with which I needed to comply and this took three months, until January 2013. For example, one “objection” was that the lower court order stated the date of the order as "03-07-12", whereas I had mentioned the date as 3 July 2012. Then they would argue that the acknowledgement of the receipt of the notice from the respondents was not received. The High Court is located next to the head post office (GPO) in Bangalore and normally it would be sent there, then directly to the GPO in Delhi and from there to the Planning Commission or to the UIDAI. Yet, the procedure was delayed because apparently the notices weren't sent. In one hearing, the court clerk said that the address of the defendant was wrong and that the address of the Planning Commission should also be included. All in all, it seemed to me like there was some deliberate attempt to delay the procedure and the dismissal of the case by the Bangalore Court seemed very questionable. As a result, in January 2013, I asked the High Court to permit me to personally hand over my appeal to the Government Council. And finally, on 17th December 2013, my appeal was heard by the Bangalore High Court!

Over the last three months, the defendants have not filed any counter affidavit. Instead, the Government Council came to the High Court and stated that I have not filed a “paper book” (which includes depositions and evidence, among other things). However, the judge stated that this is not a case which requires a “paper book”, since my appeal was about the misapplication of Order 7, Rule 11, of the Civil Procedure Code. Then the Government Council asked for more time to review the appeal and it is has been postponed.

Have there been any other recent court cases against the UID?

Yes. While all of this was going on, retired judge, Justice Puttaswamy, filed a petition in the Supreme Court, stating that the UID scheme is illegal, since it violates article 73 of the Constitution. Aruna Roy, who is an activist at the National Council for People’s Right to Information, has also filed a petition where she has questioned the UID because it violates privacy rights and the rights of the poor.

Furthermore, petitions have been filed in the Madras High Court and in the Mumbai High Court. In 2012, it was argued in the Madras High Court that the only legal provision for taking fingerprints exists under the Prisoners Act, whereas the UIDAI is taking the fingerprints of people who are not prisoners and therefore it is illegal. In 2013, Vikram Crishna, Kamayani Bahl and a few others argued in the Mumbai High Court that the right to privacy is being violated through the UID scheme. It is noteworthy that in most of these cases, the defendants have not filed any counter-arguments. The only exceptions were in the Aruna Roy and Puttaswamy cases, where the defendants claimed that the UID is secure and supported it in general. In the end, the Supreme Court directed that the cases in Mumbai and Madras should be clubbed together and addressed by it. As such, the cases filed in the Madras and Mumbai High Courts have been sent to the Supreme Court of India.

Major General Vombathakere also filed a petition in the Supreme Court, arguing that the UID scheme violates individuals' right to privacy. When the counsel for the General commenced his arguments the judge pointed to the possibility of the Government passing the NIA Bill soon, which will contain provisions for privacy, as stated by the Government. As such, the judge implied that if the Government passes such a law the argument, that the Government is implementing the scheme in a legal vacuum, may not be valid.